Section #11 - The Seneca Falls Conference organizes the fight for gender equality

Chapter 138: The Seneca Falls Convention Coalesces The Women’s Rights Movement

July 19-20, 1848

The Female Declaration Of Independence At Seneca Falls

Eight years after Mott and Stanton experience the “seating humiliation” at the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London, the topic of injustices against women comes up at a tea party they attend at Jane Mott’s house in Boston. The date is July 9, 1848, but Stanton recalls it decades later:

I poured out, that day, the torrent of my long-accumulating discontent, with such vehemence and indignation that I stirred myself, as well as the rest of the party, to do and dare anything.

What she decides to do mirrors the founding fathers, circa 1776 – hold her own continental congress and announce a Declaration of Independence from an authoritarian rule which governs her life without her consent.

Immediately the wheels are set in motion for an event to be held on July 19-20 at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York, to…

Discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of women.

To boost attendance, word goes out that reform luminaries such as Mott, Sarah Grimke, Lydia Marie Child and Frederick Douglass will be present. Next comes an agenda for the session, with Day One reserved for women only and Day Two open to both sexes. The burden of writing and delivering the keynote addresses falls to Stanton. She is assisted by the Quaker reformer, Mary McClintock, and by her attorney husband, who searches for historical precedents to make her arguments.

They decide to document the case using the frameworks laid out by the founders against Britain – beginning with a list of “Sentiments” that capture their grievances and followed by “Resolves” describing the remedies they intend to pursue in response.

July 19, 1848

Day One Of The Seneca Falls Convention

The first day of the convention opens with roughly two hundred women filling the chapel. Stanton and Mott begin with keynotes encouraging the attendees to listen with open minds to the ideas presented — especially regarding the “depth of their degradation” at the moment — and to make a personal commitment to changing the status quo.

Excitement builds when Stanton reads her “Declaration of Sentiments,” fashioned after the bill of particulars supporting the 1776 break with Britain. In this case, the rupture is cast as “one portion of the family of man…seeking a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied.”

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

Then come the ringing assertions that “all men and women are created equal,” that they share the same “unalienable rights;” that in the face of an “absolute despotism” which violates these rights, it is proper to “throw off” the sources of oppression and “demand the equal station to which they are entitled.”

With this foundation established in the preamble, Stanton enumerates the “degradations” which justify the revolution she demands. These are captured in sixteen “repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward women” intended to “establish an absolute tyranny over her.”

1. He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

2. He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

3. He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners.

4. Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

5. He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

6. He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

7. He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

8. He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given; as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women—the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

9. After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

10. He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

11. He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

12. He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education—all colleges being closed against her.6

13. He allows her in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church.

14. He has created a false public sentiment, by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

15. He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

16. He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

The call for redress, in the form of full citizenship, follows:

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation,—in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

Along with recognition of the likely resistance to be faced and a determination to press on.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to affect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

Stanton closes with a call to end the “degradation of women” so that America can finally become the “great and virtuous nation” the founders intended.

The world has never yet seen a truly great and virtuous nation, because in the degradation of women the very fountains of life are poisoned at their source.

July 19, 1848

The Demand For Voting Rights Stirs Controversy

After reading the “Sentiments” through from start to finish, Stanton opens up the floor to discuss them individually.

She finds near unanimous agreement in the hall, with one exception – the issue of women’s suffrage.

This is not a surprise to her.

Just four weeks earlier, her cousin Gerritt Smith is roundly criticized when the platform of his Liberty Party calls for universal suffrage.

She is also warned by those who help with the draft that the majority of women would prefer to focus on changes related to the social and religious arenas — and to stay away from politics. This admonition reflects the generally accepted orthodoxy that men’s intellectual superiority equips them to engage in the civic arena, while women’s innate moral superiority is best focused on home and church.

Even Lucretia Mott tries to convince Stanton to back off from the “voting rights” call:

Why Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous.

And her almost always supportive husband seconds the caution.

You will turn the proceeding into a farce.

But with Garrison-like certainty, she will have none of this — as evidenced by her decision to launch her list of “degradations” with being deprived of her “inalienable right to the elective franchise,” and “submitting to laws” in which she has no voice.

When the Sentiments are read aloud on Day One, the only stumbling block to outright consensus centers on reservations about female suffrage – and Stanton decides to hold this topic over for further discussion.

July 19, 1848

Eleven “Resolutions” Are Then Presented

Stanton’s Sentiments lay the predicate that women have been ill-treated when it comes to coverture, employment, wage equality, suing for divorce, education, admission to the ministry – even to the erosion of their self-confidence and self-respect. With all of these violations tracing to the “false supposition of the supremacy of man.”

In lawyerly fashion, she turns during the afternoon session on July 19 from the list of grievances to a list of proposed solutions. These are presented in the form of eleven “Resolutions:”

1. Resolved, That such laws as conflict, in any way, with the true and substantial happiness of woman, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and of no validity; for this is “superior in obligation to any other.

2. Resolved, That all laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and therefore of no force or authority.

3. Resolved, That woman is man’s equal—was intended to be so by the Creator, and the highest good of the race demands that she should be recognized as such.

4. Resolved, That the women of this country ought to be enlightened in regard to the laws under which they -live, that they may no longer publish their degradation, by declaring themselves satisfied with their present position, nor their ignorance, by asserting that they have all the rights they want.

5. Resolved, That inasmuch as man, while claiming for himself intellectual superiority, does accord to woman moral superiority, it is pre-eminently his duty to encourage her to speak, and teach, as she has an opportunity, in all religious assemblies.

6. Resolved, That the same amount of virtue, delicacy, and refinement of behavior, that is required of woman in the social state, should also be required of man, and the same transgressions should be visited with equal severity on both man and woman.

7. Resolved, That the objection of indelicacy and impropriety, which is so often brought against woman when she addresses a public audience, comes with a very ill grace from those who encourage, by their attendance, her appearance on the stage, in the concert, or in the feats of the circus.

8. Resolved, That woman has too long rested satisfied in the circumscribed limits which corrupt customs and a perverted application of the Scriptures have marked out for her, and that it is time she should move in the enlarged sphere which her great Creator has assigned her.

9. Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.

10. Resolved, That the equality of human rights results necessarily from the fact of the identity of the race in capabilities and responsibilities.

11. Resolved, therefore, That, being invested by the Creator with the same capabilities, and the same consciousness of responsibility for their exercise, it is demonstrably the right and duty of woman, equally with man, to promote every righteous cause, by every righteous means; and especially in regard to the great subjects of morals and religion, it is self-evidently her right to participate with her brother in teaching them, both in private and in public, by writing and by speaking, by any instrumentalities proper to be used, and in any assemblies proper to be held; and this being a self-evident truth, growing out of the divinely implanted principles of human nature, any custom or authority adverse to it, whether modern or wearing the hoary sanction of antiquity, is to be regarded as self evident falsehood, and at war with the interests of mankind.

After further discussion of each Resolve, the convention adjourns for the day, with these assertions on the table:

- Women and men are created equal;

- Women deserve equal treatment under the law;

- The traditions of coverture must be abandoned;

- All other forms of female degradation must end;

- Their educational opportunities should be expanded;

- The voice of women should be heard in public;

- Their career options should extend beyond teaching and nursing;

- They should receive equal pay for equal work;

- They must be granted the “sacred right to vote.”

July 20, 1848

Day Two At Seneca Falls

The audience on the second day grows, as men are invited to join in and speak up.

Their presence shifts some of the dynamics in the hall – one sign being that a man, James Mott, Lucretia’s husband, is asked to chair the meeting, given the “mixed” audience. Despite the revolutionary spirit in the air, traditional gender decorum still prevails at the moment.

The morning session is filled with various speeches, including a hopeful update about a “married women’s property act” currently being considered at a New York state constitutional convention. This reinforces the feeling that laws must be changed for the movement to ultimately succeed.

After lunch, Stanton re-reads the “Sentiments” and the “Resolves,” which leads to renewed debate about “female suffrage.” Ironically it is none other than the ex-slave Frederick Douglass who speaks up on the topic — arguing that if he as a black man deserves the vote, then justice demands the same right for all women. His endorsement rallies enough support in the room to have the call for suffrage included in the final documents.

The closing session is again chaired by a man, Thomas McClintock, whose wife Mary has helped plan the event. Both speak to the audience. He provides a detailed review of the onerous laws of coverture currently on the books; she follows with a plea to lobby on behalf of their repeal.

With the July temperature hovering in the nineties, the convention heads into the home stretch.

Much awaited talks by the convention’s two most famous figures, Frederick Douglas and Lucretia Mott, lead into a call for attendees to step forward and sign the Sentiments and the Resolves.

As with the 1776 Declaration of Independence, the act of affirming a controversial document in writing is not taken lightly, and less than half of those present do so. Still one hundred sign on. The gender split is 68 women and 32 men; their ages range from 14 to 81 years old; 25 are Quakers; Douglass is the lone black; only one of the signers will live to 1920 when the Nineteen Amendment finally grants female suffrage.

The end of the convention brings a sigh of relief to Stanton, Motts and the other organizers, who are generally pleased with the outcomes.

What they cannot realize at the moment is how transformative their hastily assembled event will be in the long march ahead toward equality. It is not a stretch to speak of July 10-20 at Seneca Falls in the same breath as July 4 at Philadelphia. Both put a permanent stake in the ground on behalf of revolutionary change impacting the nation.

1848

Publicity About The Convention Varies Widely

The Seneca Falls Convention does not go unnoticed in the popular press, first locally and then broadly. The reactions are about evenly split.

Some papers like the St. Louis Daily Reveille are content to simply acknowledge the event itself, without taking a stance one way or the other on the issues debated.

The flag of independence has been hoisted for the second time on this side of the Atlantic, and a solemn league and covenant has just been entered into by a convention of women at Seneca Falls, New York.

Others like The Oneida Whig go on the attack – while exhibiting in their rhetoric the exact brand of female “degradation” decried at the event.

This bolt is the most shocking and unnatural incident ever recorded in the history of womanity. If our ladies will insist on voting and legislating, where, gentleman, will be our dinners and our elbows? Where our domestic firesides and the holes in our stockings?

The Philadelphia Public Ledger and Daily Transcript is similarly clumsy in its ringing affirmation of “the ladies” who remain in their proper place, as wives and mothers, not crusaders.

A woman is nobody. A wife is everything… and a mother is, next to God, all powerful….The ladies of Philadelphia, therefore, …are resolved to maintain their rights as Wives, Belles, Virgins, and Mothers, and not as Women

The Seneca County Courier finds the convention’s assertions startling, and their resolutions radical:

The meeting was novel in its character and the doctrines broached in it are startling to those who are wedded to the present usages and laws of society. The resolutions are of the kind called radical.”

Meanwhile, leave it to Horace Greeley, the 37 year old editor of The New York Tribune, to support that which so many of his colleagues consider radical. Greeley dabbles in various utopian movements, becomes an outspoken abolitionist, adopts a vegetarian diet — and his staff includes Margaret Fuller, one of the earliest and most articulate advocates for female equality. Greeley’s editorial applauds the revolutionary spirit and proposed reforms at Seneca Falls, albeit with some reservations about suffrage:

When a sincere republican is asked to say in sober earnest what adequate reason he can give, for refusing the demand of women to an equal participation with men in political rights, he must answer, None at all…however unwise and mistaken the demand, it is but the assertion of a natural right, and such must be conceded.

1848 Forward

The Intrepid Female Agents Of Change

And so time will pass.

Some thirty years after the Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton recalls the aftermath in particularly painful terms:

So pronounced was the popular voice against us, in the parlor, press, and pulpit that most of the ladies who had attended the convention and signed the declaration, one by one, withdrew their names and influence and joined our persecutors. Our friends gave us the cold shoulder and felt themselves disgraced by the whole proceeding.

For her and others, the battle for gender equality proves every bit as challenging and lengthy as black emancipation.

The sage Lucretia Mott foretells this early on, with a warning to her young colleagues:

Thou wilt have hard work to prove the intellectual equality of women with men – facts being so against such an assumption in the present stage of women’s development.

For those in the front lines, the fight for the rights of women follows naturally from their efforts against slavery.

The plight of America’s slaves and women is by no means equivalent! But both groups suffer many of the same indignities. Both share a sense of bondage, be it to a master or a husband. Both are systematically deprived of education and of basic legal rights and remedies. Both are often pushed beyond their physical limits, between constant pregnancies and daily labor. It is not by accident that Stanton chooses the word “degradations” to characterize the experience.

But above all else, what nineteenth-century American women have in common with slaves is the stigma of being born as a lesser being – the stigma that leads Lucy Stone’s mother to apologize to her father for delivering another girl.

Fighting back from this stigma requires courage. As Anthony says:

Cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing can never bring about a reform

The litmus test of leadership falls to those brave women who take to the lecture circuit – in front of an audience including men, often appalled at the sight of a short-haired woman, dressed in a jacket and trousers, speaking up and challenging the role they have been assigned in society, by the Bible, the common law, and tradition.

The traveling routine itself is a challenge: lining up venues, often finding either tiny or hostile audiences, flopping into rented rooms, and then moving on to the next site, especially, as Amelia Bloomer reports, in the dead of winter:

My ardor in the cause of women chills at the thought of stage rides in temperatures of twenty-five below zero.

Even that most tenacious lecturer, Lucy Stone, recalls the physical and mental toll of these tours:

I am completely exhausted by long & hard field service, and my back is giving me so much pain, I am going home to rest.

For those who dare, however, the moments of public speaking are quintessentially liberating.

And once the battle is joined at Seneca Falls, the women’s rights movement picks up momentum. The lessons learned from the campaign against slavery are soon repeated – more organized conventions, the creation of “societies,” petitions to congress, pamphlets, and publicity.

Stanton’s essays are a constant goad to all opponents, especially those in government. In February 1854, she makes the case to the New York state legislature:

We demand full recognition of our rights as citizens of the Empire State. We are persons; native, free born citizens; property-holders, tax-payers. We support ourselves, and, in part, your schools, churches, poor-houses, prisons, army, navy, the whole machinery of government, and yet we have no voice in your councils. We have every qualification required by age constitution, necessary to the legal other, but the one of sex.

In 1869 the National Women Suffrage Association starts up, with Stanton as president and Anthony alongside

That same year also finds the two of them editing and publishing their own newspaper, The Revolution, dedicated to the cause.

As with almost all reform groups, an internal schism occurs, in this case over the 14th and 15th Amendments, which guarantee the rights of blacks, including the vote for men. Stanton and Anthony are outraged by the absence of equal entitlements for women. As Stanton tells congressmen at the time:

You now place the negro, so unjustly degraded by you, in a superior position to your own wives and mothers.

Meanwhile Lucy Stone, along with Paulina Wright Davis and her clerical sister-in-law, Antoinette Brown, are unwilling to try to derail any advances for the former slaves, even if they are disappointed by the outcome. This leads them to found a separate group, the American Women Suffrage Association. Unlike the NWSA, it allows men to participate and tends to favor the Republican Party.

The NWSA or Stanton-Anthony wing of the movement is also inclined to more confrontational tactics, especially “storming the polls” on election days. In 1872, Stanton herself votes, before being arrested, fined, and released.

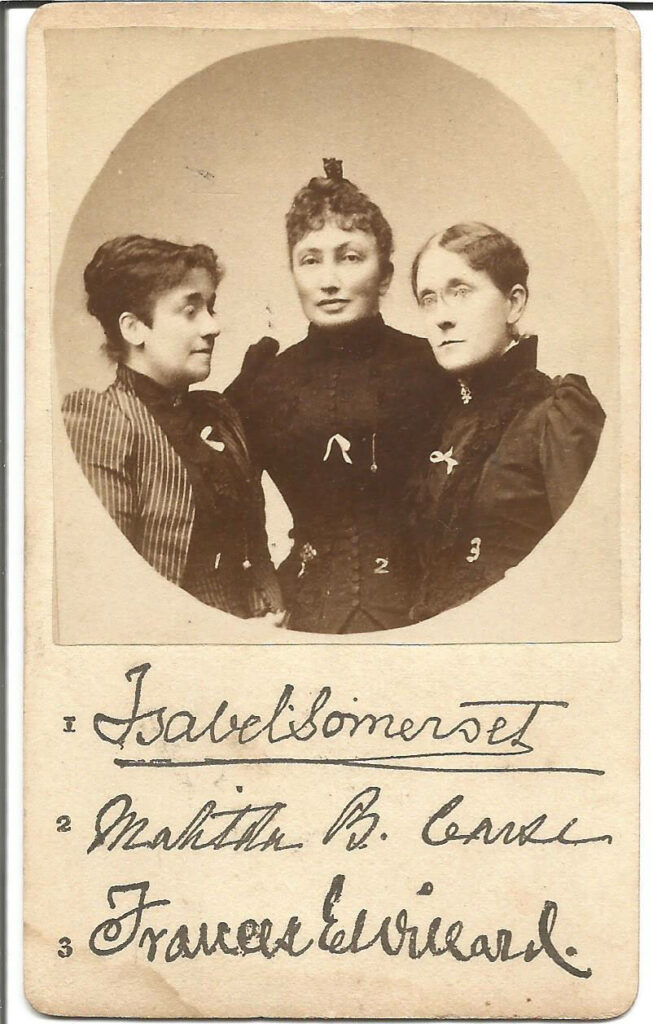

These wounds heal by 1890, and the old warriors reunite under the merged banner, National American Women Suffrage Association, with Anthony serving as president. She is seventy years old at the time, with Stanton at seventy-five and Lucy Stone at seventy-two.

Their time on stage is almost up. Stone dies in 1893, Stanton in 1902, Anthony in 1906. So none live to see women granted the vote, either in America in 1920 or in the UK in 1928.

They will, however, remain eternally together, along with Lucretia Mott and others, on the rolls of those who liberated women from bondage, always, as Stanton said, by overcoming fear and speaking the truth.

The moment we begin to fear the opinions of others and hesitate to tell the truth that is in us, and from motives of policy are silent when we should speak, the divine floods of light and life no longer flow into our souls

A next generation of leaders will carry this tradition forward – and, fittingly, it includes both Harriot Stanton Blatch (1856-1940) and Alice Stone Blackwell (1857-1950), every inch their mother’s daughters.