Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 203: Open Warfare Breaks Out Across Kansas

May 21, 1856

Pro-Slavery Forces Sack The Town Of Lawrence

One day after Sumner delivers his “Crimes In Kansas” speech, another turning point occurs in the saga of the territory, this time in the Free State capital of Lawrence.

At the center of this incident is Samuel Jones, Sheriff of Douglas County. Jones is a Virginian by birth who emigrates to Westport, Missouri in 1854 at age thirty-five years to become postmaster. He favors opening up Kansas as a Slave State, and joins the Border Ruffians in stealing the congressional seat election on March 30, 1855. Along with Samuel Lecompte – President Pierce’s choice as Chief Justice of the territory’s Supreme Court — Jones co-founds the town of Lecompton, and opens an initially prosperous lumber and saw milling operation there.

In September 1855, he is appointed Sheriff of Douglas County by the Pro-Slavery legislature. His domain includes Lawrence, where he is christened the “bogus Sheriff” by townspeople, who repeatedly threaten him, as in this message signed by the “Secret Twelve:”

Sheriff Jones—You are notified that if you make one more arrest by the order of any magistrate appointed by the Kansas Bogus Legislature, that in so doing you will sign your own Death Warrant. Per order. SECRET TWELVE

In turn a Free State posse abducts his prisoner on the way to jail, provoking the Wakarusa War incident in November 1855. In April 1856 he is twice pummeled by mobs and then suffers a gunshot wound in the back while trying to make arrests in Lawrence.

On May 15, 1856, tension rises when Free State Governor Charles Robinson is jailed in response to warrants issued by Judge Lecompte.

On May 21, Jones returns to Lawrence to make additional arrests, only this time he arrives on the scene with a force of 700 men, some Federal militia and others pro-slavery marauders itching for a battle. To signal their determination, they haul four cannon to the scene.

Confronted with this overwhelming firepower, the residents of Lawrence allow U.S. Deputy Marshal Fain to enter the town and carry out his duties peacefully. Having completed his assignment, the head of the Federal militia dismisses his men from duty – which leaves Sheriff Jones and the remaining pro-slavery gang in place.

This is their chance to wreak havoc on Lawrence and they take it. They sweep into town and turn their attention first to the offices of the two leading opposition newspapers, the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State. Both are torn apart, with their presses and type dumped in the Kansas River.

The Free State Hotel, headquarters of the resistance movement, is next, with the four cannon lined up facing the building and ex-U.S. Senator David Atchison directing the fire. When the structure walls survive, kegs of powder are piled inside and the building is burned to the ground.

General looting follows along with the destruction of the home of Charles and Sarah Robinson. Robinson himself is already in jail, having been arrested on May 10 and charged with treason for his role as the Free Stater’s chosen Governor of Kansas.

As the invaders depart, Sheriff Sam Jones is said to exclaim:

This is the happiest day of my life, I assure you.

May 24-25, 1856

John Brown Takes Revenge In His Potawatomie Massacre

With the town of Lawrence still in shambles from the Pro-Slavery assault, the Old Testament abolitionist, John Brown, responds with an eye for an eye.

Brown is fifty-six years old when he moves in October 1856 from his home in New Elba, New York to Potawatomie Creek, Kansas, to join several of his sons in the crusade against slavery. He regards this as his personal destiny, having “consecrated his life” to the cause back in 1837 in response to the murder of Elijah Lovejoy.

His business and family affairs are marked for years by grievous losses, but these only affirm his belief that the Lord has a great purpose still in store for him – namely to lead a black army crusade in the South to kill plantation owners and free the slaves. He will regard this as an act of “honorable violence.”

But first he is called upon to avenge the sack of Lawrence.

Along with four of his sons Brown sets out on the night of May 24, 1856 after two main targets – a member of the Pro-Slavery legislature named Allen Wilkinson, and another man, “Dutch Henry” Sherman.

In their search for Wilkinson, they arrive first at the home of one James Doyle, a pro-slavery man living in Potawatomie. His wife Mahala describes what happens next:

About 11 o’clock at night, after we had all retired, my husband, James P. Doyle, myself, and our seven children (William 22, Drury 20, John 16, Polly Ann 13, James 10, Charles 8, Henry 5) when we heard some persons come into the yard and rap at the door and call for Mr. Doyle, my husband. My husband got up and went to the door. Those outside inquired for Mr. Wilkson, and where he lived. My husband told them that he would tell them. (He) opened the door, and several came into the house, and said that they were from the army. My husband was a pro-slavery man. They told my husband that he and the boys must surrender, they were their prisoners. These men were armed with pistols and large knives. They first took my husband out of the house, then they took two of my sons-the two oldest ones, William and Drury-out, and then took my husband and these two boys, William and Drury, away. My son John was spared, because I asked them in tears to spare him. In a short time afterwards I heard the report of pistols. I heard two reports, after which I heard moaning, as if a person was dying; then I heard a wild whoop. They had asked before they went away for our horses. We told them that the horses-were out on the prairie. My husband and two boys, my sons, did not come back any more. 1 went out next morning in search of them, and found my husband and William, my son, lying dead in the road near together, about two hundred yards from the house. My other son I did not see any more until the day he was buried. I was so much overcome that I went to the house. They were buried the next day. On the day of the burying I saw the dead body of Drury.

Mahala sixteen year old son, John, adds more gory details to the account:

On Saturday night…a party of men came to our house; we had all retired; they roused us up, and told us that if we would surrender they would not hurt us. They said they were from the army; they were armed with pistols and knives; they took off my father and two of my brothers, William and Drury. We were all alarmed. They made inquiries about Mr. Wilkson, and about our horses. The next morning was Sunday, the 25th of May, 1856. I went in search of my father and two brothers. I found my father and one brother, William, lying dead in the road, about two hundred yards away. I saw my other brother lying dead on the ground, about one hundred and fifty yards from the house, in the grass, near a ravine; his fingers were cut off, and his arms were cut off; his head was cut open; there was a hole in his breast. William’s head was cut open, and a hole was in his jaw, as though it was made by a knife, and a hole was also in his side. My father was shot in the forehead and stabbed in the breast. I have talked often with northern men and eastern men in the Territory, and these men talked exactly like (them)…An old man commanded the party; he was a dark complected, and his face was slim. We had lighted a candle, and about eight of them entered the house; there were some more outside. The complexion of most of those eight whom I saw in the house were of sandy complexion. My father and brothers were proslavery men, and belonged to the law and order party.

James Doyle is shot to death and his two older sons, William and Drury have been hacked to death with broadswords by the time Brown and his men leave their farm. But that much bloodshed is not enough.

After killing the three Doyles, the search continues for Allen Wilkinson, a member of the pro slavery “Bogus Legislature.” Brown’s band arrives at his home after midnight, and haul him out of bed. His wife, Louisa Jane, provides the rest of the story:

I am the widow of the late Allen Wilkinson. We came to Kansas, from Tennessee, in October, 1854; went to our claim, on Pottowatomie creek, about the 12th day of November following. Said claim, where my husband lived at the time of his death, lies in Franklin county, Kansas Territory, about eight miles from Ossawatomie, and the same distance from the mouth of Pottowatomie creek.

On the 25th of May last, somewhere between the hours of midnight and daybreak, cannot say exactly at what hour, after all had retired to bed, we were disturbed by barking of the dog. I was sick with the measles, and woke up Mr. Wilkinson, and asked if he “heard the noise, and what it meant?” He said it was only some one passing about, and soon after was again asleep. It was not long before the dog raged and barked furiously, awakening me once more; pretty soon I heard footsteps as of men approaching; saw one pass by the window, and some one knocked at the door.

I asked, who is that? No one answered. I awoke my husband, who asked, who is that? Some one replied, I want you to tell me the way to Dutch Henry’s. He commenced to tell them, and they said to him, “Come out and show us.” He wanted to go, but I would not let him; he then told them it was difficult to find his clothes, and could tell them as well without going out of doors. The men out of doors, after that, stepped back, and I thought I could hear them whispering; but they immediately returned, and, as they approached, one of them asked of my husband, “Are you a northern armist?” He said, “I am.” I understood the answer to mean that my husband was opposed to the northern or freesoil party. I cannot say that I understood the question.

My husband was a pro-slavery man, and was a member of the territorial legislature held at Shawnee Mission. When my husband said “I am,” one of them said, “You are our prisoner. Do you surrender?” He said, “Gentlemen, I do.” They said, open the door. Mr. Wilkinson told them to wait till he made a light; and they replied, if you don’t open it, we will open it for you. He opened the door against my wishes, and four men came in, and my husband was told to put on his clothes, and they asked him if there were not more men about; they searched for arms, and took a gun and powder flask, all the weapon that was about the house.

I begged them to let Mr. Wilkinson stay with me, saying that I was sick and helpless, and could not stay by myself. My husband also asked them to let him stay with me until he could get some one to wait on me; told them that he would not run off, but would be there the next day, or whenever called for. The old man, who seemed to be in command, looked at me and then around at the children, and replied, “you have neighbors.” I said, “‘so I have, but they are not here, and I cannot go for them” The old man replied, “it matters not,” I told him to get ready. My husband wanted to put on his boots and get ready, so as to be protected from the damp and night air, but they wouldn’t let him. They then took my husband away.

One of them came back and took two saddles; I asked him what they were going to do with him, and he said, “take him a prisoner to the camp.” I wanted one of them to stay with me. He said he would, but “they would not let him.” After they were gone, I thought I heard my husband’s voice, in complaint, but do not know; went to the door, and all was still.

Next morning Mr. Wilkinson was found about one hundred and fifty yards from the house, in some dead brush. A lady who saw my husband’s body, said that there was a gash in his head and in his side; others said that he was cut in the throat twice. On the Wednesday following I left for fear of my life. I believe that they would have taken my life to prevent me from testifying against them for killing my husband. I believe that one of Captain Brown’s sons was in the party, who murdered my husband; I heard a voice like his. I do not know Captain Brown himself. I have two small children, one about eight and the other about five years old. The body of my husband was laid in a new house; I did not see it. My friends would not let me see him for fear of making me worse. I was very ill.

The old man, who seemed to be commander, wore soiled clothes and a straw hat, pulled down over his face. He spoke quick, is a tall, narrow-faced, elderly man. I would recognize him if I could see him. My husband was a poor man. I am now on my way to Tennessee to see my father, William Ball, who lives in Haywood county. I am enabled to go by the kindness of friends in this part of Missouri. Some of the men who took my husband away that night were armed with pistols and knives. I do not recollect whether all I saw were armed. They asked Mr. W. if Mr. McMinn did not live near. My husband was a quiet man, and was not engaged in arresting or disturbing any body. He took no active part in the pro slavery cause, so as to aggravate the abolitionists; but he was a pro-slavery man.

Four are now dead, but the savagery continues into the morning of May 25.

Their attention now turns to “Dutch Henry” Sherman, and in searching for him, they arrive at the home of James Harris, who evidently lives nearby. Around 2AM on May 25, Harris is awakened by John Brown and his son, Owen, both of whom he recognizes. The Brown’s ask Harris as to the whereabouts of “Dutch Henry” Sherman, and then interrogate three other men who are guests at the house. One of them happens to be William Sherman, Henry’s brother, and that seals his fate.

James Harris provides the following testimony on the proceedings:

I reside on Pottowatomie creek, near Henry Sherman’s, in Kansas Territory. I went there to reside on the last day of March, 1856, and have resided there ever since. On last Sunday morning, about two o’clock, (the 25th of May last,) whilst my wife and child and myself were in bed in the house where we lived, we were aroused by a company of men who said they belonged to the northern army, and who were each armed with a sabre and two revolvers, two of whom I recognized, namely, a Mr. Brown, whose given name I do not remember, commonly known by the appellation of “old man Brown,” and his son, Owen Brown.

They came in the house and approached the bed side where we were lying, and ordered us, together with three other men who were in the same house with me, to surrender; that the northern army was upon us, and it would be no use for us to resist. The names of these other three men who were then in my house with me are, William Sherman, John S. Whiteman, the other man I did not know. They were stopping with me that night. They had bought a cow from Henry Sherman, and intended to go home the next morning.

When they came up to the bed, some had drawn sabres in their hands, and some revolvers. They then took into their possession two rifles and a Bowie knife, which I had there in the room-there was but one room in my house-and afterwards ransacked the whole establishment in search of ammunition. They then took one of these three men, who were staying in my house, out. (This was the man whose name I did not know.) He came back. They then took me out, and asked me if there were any more men about the place. I told them there were not. They searched the place but found none others but we four.

They asked me where Henry Sherman was. Henry Sherman was a brother to William Sherman. I told them that he was out on the plains in search of some cattle which he had lost. They asked if I had ever taken any hand in aiding pro slavery men in coming to the Territory of Kansas, or had ever taken any hand in the last troubles at Lawrence, and asked me whether I had ever done the free State party any harm or ever intended to do that party any harm; they asked me what made me live at such a place. I then answered that I could get higher wages there than anywhere else. They asked me if there were any bridles or saddles about the premises. I told them there was one saddle, which they took, and they also took possession of Henry Sherman’s horse, which I had at my place, and made me saddle him. They then said if I would answer no to all the questions which they had asked me, they would let loose.

Old Mr. Brown and his son then went into the house with me. The other three men, Mr. William Sherman, Mr. Whiteman, and the stranger were in the house all this time. After old man Brown and his son went into the house with me, old man Brown asked Mr. Sherman to go out with him, and Mr. Sherman then went out with old Mr. Brown, and another man came into the house in Brown’s place. I heard nothing more for about fifteen minutes. Two of the northern army, as they styled themselves, stayed in with us until we heard a cap burst, and then these two men left.

That morning about ten o’clock I found William Sherman dead in the creek near my house. I was looking for Mr. Sherman, as he had not come back, I thought he had been murdered. I took Mr. William Sherman out of the creek and examined him. Mr. Whiteman was with me. Sherman’s skull was split open in two places and some of his brains was washed out by the water. A large hole was cut in his breast, and his left hand was cut off except a little piece of skin on one side. We buried him.

As brutal as these attacks are, Brown is able to dismiss them as “righteous” in their intent. As he later says:

It is better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should pass away by a violent death than that slavery should live on.

Others are not so dismissive.

Up to the night of May 24-25, the actual death toll in Kansas has been minor. One man is killed during the Wakarusa War incident, and one dies in the raid on Lawrence, struck by a falling brick.

Thus the killing of Brown’s five victims, accompanied by the gruesome character of their wounds and a certain sense of randomness to their fate, seems different to those on both sides – almost a signal that prior restraints need no longer apply to future confrontations.

June 2, 1856

The Violence Continues At The Battle Of Black Jack

The Potawatomie murders seem to reflect John Brown’s rage over the accumulated humiliations suffered by his anti-slavery camp. Lawrence is helpless against Sheriff Jones’ marauders on May 21; Sumner cannot defend himself against Brooks on May 22; Free State “Governor” Charles Robinson is arrested on May 24, while “Senator” Reeder flees for his own safety.

Brown calls Robinson “a perfect old woman” and the Topeka legislature “more talk than cider.” Potawatomie is his message that the weakness cannot go on:

We must show by actual work that there are two sides to this thing and that they can not go on with this impunity,

Robinson views the act differently, saying that the massacre will simply give Governor Shannon another excuse to call in more federal troops against the Free Staters – and indeed that is what he does.

But Brown is undeterred by the criticism, and organizes his Potawatomie Rifles Brigade to pursue the fight. His next target is U.S. Deputy Marshal H.C. Pate, who also serves in the territorial militia and who participated in the assault on Lawrence. In seeking to arrest Brown for his murders, Pate arrests two of his sons – John Jr. and Jason. Brown intends to free them.

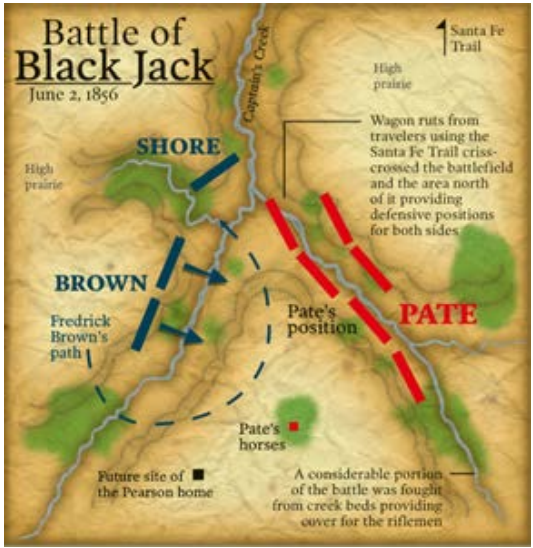

On June 2, Pate and a band of some two dozen men are camped at Black Jack, twenty miles south of Lawrence, along Captain’s Creek.

They are attacked there shortly before dawn by Brown and Captain Samuel Shore’s brigade. A pitched battle ensues, lasting for upwards of three hours, It ends when Brown slips several men into Pate’s rear, convincing him that reinforcements have appeared from Lawrence, and that he is surrounded. In response, he raises a white flag and surrenders along with twenty-three of his men. During the skirmish four of Brown’s men are wounded in action.

Brown proceeds to draft a formal “Article of Agreement” which calls for an exchange of prisoners: Brown’s two sons in return for Pate and his lieutenant, W. B. Brocket. Both sides sign and the battle is over.

Some historians will later refer to this engagement at Black Jack as the “opening battle in the Civil War.”

For Governor Shannon it is one more signal that events are out of control in Kansas, and that he is out of answers on restoring order.