Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 28: Burr’s Filibustering Campaign Signals U.S. Colonial Intentions

1805-1806

Burr Plans To Create An Empire In The Southwest

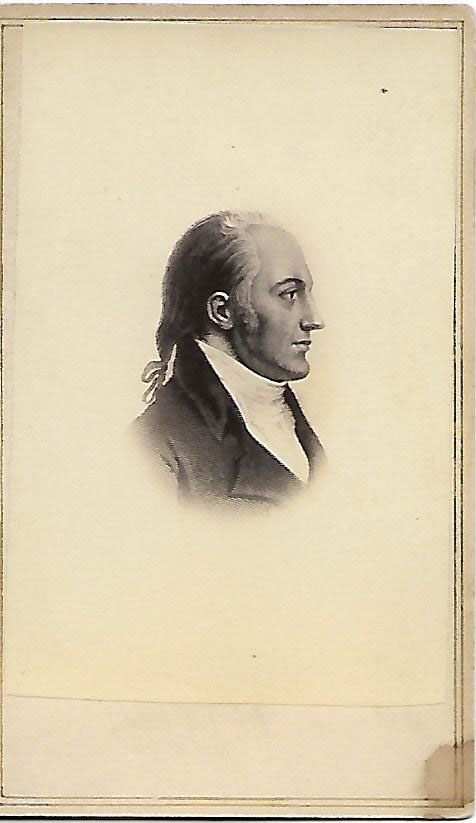

Aaron Burr is one of those famous figures in American history who climb to the pinnacle of national fame only to fall back into the ranks of the notorious.

He is born on February 6, 1756, in Newark, New Jersey, to parents steeped in religious ties. His mother, Esther, is the daughter of Jonathan Edwards, the famous Puritan minister, whose Calvinist oriented tract, “Sinners In The Hands Of An Angry God,” helped fuel the First Great Awakening in 1741. His father, Aaron Sr., is a Presbyterian minister and second president of The College of New Jersey (later Princeton).

But both parents die before Aaron reaches the age of three, and he and his sister are left in the care of their uncle, Timothy Edwards, who raises them within the stern traditions of Calvinism. This fails to sit imultaneously precocious and rebellious. After trying to run away from home, he applies for admission to the College of New Jersey (Princeton) at age eleven. Two years later, he is allowed in, and graduates at sixteen, in 1772. Despite being pushed toward a career in the ministry, his inclinations are far removed from the Calvinistic austerity he has experienced as a youth. Instead he takes up the law – and is three years into his studies when the Revolutionary War breaks out.

Burr immediately enlists in the Continental army, where his affection for combat over a four year period earns him both glory and recognition. He fights with Montgomery in 1775 at Quebec, helps Washington and Hamilton escape from their 1776 trap in Manhattan, rises to Lt. Colonel status in 1777, survives Valley Forge and takes part in the pivotal 1778 battle at Monmouth. By 1779 the war has taken a sufficient toll on his health that he resigns his commission and returns to his legal pursuits.

He opens a law office in Albany in 1782 and that same year marries Theodosia Prevost, a widow with five children, who, at 36, is ten years his senior. Despite dalliances, Burr stays with his wife until her death in 1794, and forever dotes on their daughter, also named Theodosia.

In 1784, Burr enters the rough and tumble world of New York politics, as an Anti-Federalist. He begins as a State Assemblyman, then is chosen as Attorney General, under Governor George Clinton. He serves as U.S. Senator from 1791 to 1797, after defeating General Phillip Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law, in his race.

His ambition leaps ahead, and he expects to be elected Vice-President in 1796, but his electoral votes fall behind Adams, Jefferson and Pinckney. Still he tries again in 1800, ties Jefferson in electoral votes, but then loses out in the House run-off engineered by Hamilton.

After the election of 1800, Burr loses Jefferson’s trust, and is dropped from the ticket in 1804. This leads to his decision to run for Governor of New York, but he is soundly defeated.

He blames the loss on political smears, coming from his long-time adversary, Hamilton. The result is a series of letters between the two men, a “challenge” issued by Burr, and the fatal duel at Weehauken Heights that leaves Hamilton dead and Burr’s reputation forever tarnished.

With his political days over, Burr joins his old Revolutionary War friend, Major General James Wilkinson, in a plot that will lead to his arrested for treason.

Burr has convinced Jefferson to name Wilkinson Governor of the Louisiana Territory. But he returns the favor first by trying to break off Kentucky and Tennessee from the Union, then by conspiring with Spain to hamper American access to the port of New Orleans, and finally by initiating a “filibustering” scheme with Burr in 1805 to set up an independent confederation of states across the South under his rule as dictator.

Burr’s role in the filibustering plan involves raising a small army and heading to New Orleans to foment rebellion. He contacts British officials in an attempt to secure financial backing but is rebuffed. He then meets with one Harman Blennerhasset, who owns an island on the Ohio River, where Burr will store weapons and train troops.

Next comes a visit to New Orleans, supposedly to visit land he owns in the Tejas Province, but actually intended to recruit locals who support an invasion into Mexico.

February 19, 1807

The Former VP Is Betrayed And Arrested For Treason

By 1806, however, the plan begins to unravel. The Ohio state militia raids Blennerhasset’s Island, and Burr fails in his efforts to gather troops.

The scurrilous Wilkinson, fearing for his own reputation, informs Jefferson that Burr is plotting an insurrection. Jefferson is livid and a warrant is issued for Burr’s arrest.

He is taken into custody in Mississippi, escapes briefly, and is then re-captured on February 19, 1807. He is shipped back to Washington to stand trial for treason.

September 1, 1807

The Trial Ends With Acquittal And Shame

The trial itself captures the nation’s attention. It is held over seven months beginning in the summer of 1807 at the Federal Circuit Court in Richmond, Virginia. The judge is none other than Chief Justice John Marshall, who is frequently at odds with Jefferson. Those defending Burr include Edmund Randolph, former Attorney General and Secretary of State under Washington. An equally stellar line-up of prosecutors – micromanaged from the start by the President – aim to take Burr’s life for treason.

Subpoenas are issued to a host of possible witnesses. Included here is Andrew Jackson, ex Senator from Tennessee, who had met with Burr, and is suspected of encouraging his move into Mexico. Also President Jefferson himself, whose plea to avoid the subpoena is rejected by Marshall, again asserting that not even the President is above the law. (In the end, neither will actually testify.)

On June 15, 1807, the Grand Jury hears Wilkinson testify against Burr, but the defense pokes numerous holes in his account, and he barely escapes the just indictment he deserves. Nine days later, they enter charges against Burr for treason — “levying war on the United States” in actions on Blennerhasset’s Island – and for “high misdemeanors” related to organizing a military action against Spain in violation of the 1794 Neutrality Act.

As the trial itself closes, however, Marshall instructs the jury that the 1787 Constitution sets the bar very high for proving treason.

To establish the crime of treason the prosecution must prove that an overt act of treason had been committed by the defendant in a war and that, under the Constitution, the overt act must be testified to by two witnesses and must have occurred in the district of the trial.

After deliberations, the jury concludes the prosecution has failed to show enough evidence to sustain either charge.

Burr walks out of the courtroom as a free man, despite the ongoing certainty expressed by Jefferson and others that he is guilty on all counts.

Henceforth his name will be synonymous across America for slaying Hamilton and plotting treason. In response, Burr flees to England, hoping that time and distance will eventually allow his return to the States. And this proves to be the case. In 1813 he is back home, living momentarily under an assumed name. His star, which shines so brightly up to 1804, is now dimmed; but he is left with his notoriety as he roams the streets of his beloved New York before dying in 1836, at age eighty, on Staten Island.