Section #7 - A populist western president stands against Nullification and for tribal relocation

Chapter 64: More Tribal Land Evictions Triggers The Blackhawk War

March 18, 1831

The Marshall Court Denies Cherokee’s Pleas To Keep Their Land

Ever since the end of the Revolutionary War, settlers crossing the Appalachians into land forfeited by Britain have encountered resistance from Native American tribes defending their homelands.

Between 1791 and 1794, U.S. troops are deployed to Ohio and Indiana to defeat the Shawnees.

Then hostility increases during the War of 1812 as the Shawnees, Miami and other tribes band with the British, hoping to end the U.S. intrusions. Several landmark battles follow, along with growing public animosity toward the tribes. In 1811 General William Henry Harrison defeats a tribal confederation in Indiana at Tippecanoe, and in 1813 Chief Tecumseh is killed along the Canadian border.

General Andrew Jackson then crushes the Red Stick Creeks in 1814 at Horseshoe Bend, Alabama, and in 1818 attempts to drive the Seminoles out of Florida with mixed results.

Various one-sided treaties follow the major tribal defeats with sizable chunks of territory ceded to the U.S. victors. Thus by the time Jackson becomes President, the wheels have already been set in motion to allow white settlers to usurp the homelands of the eastern Indian tribes. Momentum picks up here on December 28, 1828, when the Georgia legislature passes a law transferring ownership of all Cherokee territory to the state.

In May 1830, an Indian Removal Act barely passes the U.S. Congress, with the North opposing it and the South vigorously in support. This Act calls for forced transfer of the so-called “civilized tribes” from the southeast to their new reservations west of the Mississippi in the Oklahoma territory. The contrived rationale is that relocation will give the Indians a better chance to master agriculture and “become modernized” in their ways. Also, that reimbursements in land or cash will be offered to those displaced.

In June 1830, Chief John Ross, backed by Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, seeks an injunction in federal court to stop “the annihilation of the Cherokee tribe as a political society.” His argument is based on the notion that the Cherokees are a “foreign nation” – and, as such, not subject to Georgia’s jurisdiction or laws.

On March 18, 1831, the Marshall court hands down its ruling in Cherokee Nation v Georgia. It totally ignores the central issue regarding the “fairness” of the Georgia state legislature’s action against the Cherokees. Instead, by a 4-2 vote, it denies Ross’s “foreign nation” claim, and, in turn, his right to even petition the court for a ruling on the merits of his case.

An Indian tribe or nation within the United States is not a foreign state in the sense of the constitution, and cannot maintain an action in the (federal) courts of the United States.

Thus the Indians – like the Africans – are denied citizenship in the United States.

Their political identity also disappears in the process, and their status, as Marshall puts it, becomes that of “a ward to its guardian.”

In this case the guardian will prove forever unsympathetic to their cause.

April 6 to August 2, 1832

Sauk Tribes Fight Back In The Black Hawk War

With the law on his side, Andrew Jackson begins to act against the Native Americans.

In 1831 he orders General Winfield Scott to begin the “removal” process, using regular U.S. Army troops and local militia where needed.

A few tribes decide to resist.

One such rebellion breaks out in northwestern Illinois in April of 1832.

It is led by the Sauk Chief, Black Hawk, who hopes to build a confederation of resisters similar to what the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh achieved in 1811, in the Indiana Territory.

Black Hawk is 65 years old at the time. Since his youth he has fought against the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis which surrendered some 5 million acres of his homeland, mostly in the southern Wisconsin/Michigan Territory.

During the War of 1812, the British name him a Brevet Brigadier General, and his Sauks fight alongside the crown to stem the tide of white settlers.

But by June 1831, it seems apparent that his battle is lost, and Black Hawk leads his villagers west across the Mississippi into the “unorganized territory.”

Ten months later he changes his mind. He convinces his Sauk tribesmen to recross the river and reclaim their ancestral lands. To assemble a credible fighting force he seeks support from a variety of other local nations, including the Kickapoos, Meskwaki, Fox, Ho Chunks and Potawatomi nations. Together they hope to form what will be known as the “British Band,” given their historical linkage to the redcoats.

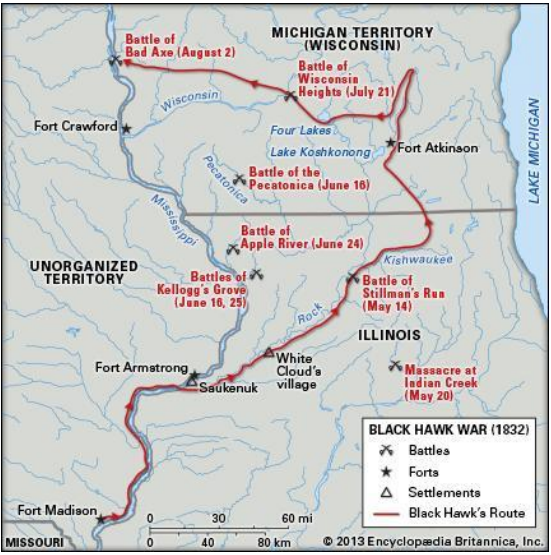

On April 6, 1832, the British Band of roughly 1,000 warriors and their families crosses the Mississippi and heads northeast along the Rock River toward the southern border of Wisconsin.

By May 14 they have travelled 90 miles and reached Old Man’s Creek, without yet being joined by any of the allies they anticipated. At this point, with elements of the Illinois militia in his front, Chief Black Hawk is ready to abandon his quest. He sends emissaries to notify the militia of this intent, but they are fired upon.

A melee ensues, with Black Hawk’s warriors routing woefully disorganized troops under Major Isiah Stillman. This event is remembered as the Battle of Stillman’s Run, ending in humiliation for the Illinois militia leading the Governor to call up a force capable of pursuing the Indians.

Over the next ten weeks, Black Hawk fights a series of skirmishes while swinging through southern Wisconsin and eventually retreating toward the Mississippi River. On July 21 the Battle of Wisconsin Heights is fought in Dane County, with remnants of the British Band slipping away to the west. Twelve days later the Black Hawk War ends at the Battle of Bad Axe, where US troops under General Henry Atkinson and Major Henry Dodge wipe out the remaining rebels.

Chief Black Hawk himself is captured and sent to Washington D.C., where he meets with the President before being sent to jail for a short time. There he tells his life story to a reporter who turns it into a biography, making him a celebrity until his death in 1838.

The war which bears his name is also remembered for two famous participants who play cameo roles.

One is 23 year old Abraham Lincoln, living in New Salem, Illinois, and working as a clerk in a village store, when he enlists in the Illinois militia. He serves for roughly 12 weeks, mainly as Captain of a rifle company in the 31st Regiment out of Sangamon County. Lincoln sees no combat during the war, and later jokes that his greatest challenge was fighting mosquitoes.

The other is 24 year old Jefferson Davis, graduate of West Point in 1828 and in the Regular Army as a second Lieutenant, stationed at Ft. Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Davis is in Mississippi on furlough during the conflict but is later assigned to escort Chief Black Hawk to Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis.