Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 131: Two Splinter Parties Nominate Their Presidential Candidates Early On

September 10-11, 1847

The Native American Party Selects Zachary Taylor

With the Mexican War winding down, Lewis Levin and his anti-immigrant Native American Party try to get a jump on the 1848 election by holding their first national convention.

The party has won six House seats in the 1844 race but is down to one – Levin himself — after the off-year balloting. Its goal now is to revitalize itself, arrive at a platform, and try to strengthen its organization and broaden its base of voters.

The name of Levin’s party will vary over the next decade.

At first it’s known as the American Republican Association. This morphs into the Native American Party by 1847, or the American Party for short. An off-shoot calling itself The Order of the Star Spangled Banner surfaces in 1849, before a skeptical journalist, Horace Greeley, finds members reciting a set response when asked about the party principles – “I know nothing.”

Greeley responds by handing the group its enduring nickname, the “Know Nothing Party.”

The party convention is held on September 10-11 at the Assembly Building in Philadelphia, with roughly one hundred delegates in attendance.

A full party platform won’t be fleshed out until 1852, but for now, they agree on several things:

- The country should “belong” to American born, white Protestant citizens.

- The sharp rise in overall immigration in the 1840’s threatens this outcome.

- The danger is compounded by the fact that many immigrants are Catholics, beholden to Rome.

In turn, the solution to “saving the country” lies in a host of actions aimed at the “foreign invaders” – from shutting down further immigration to waging “war to the hilt” against Catholics already in the country.

When the time comes for the American Party to nominate their choice for 1848, they settle on the warrior of the Mexican War, General Zachary Taylor.

For Vice-President it is 64 year old Henry A. S. Dearborn, son of Revolutionary War General Henry Dearborn, and current Mayor of Roxbury, Massachusetts.

October 20, 1847

The Liberty Party Splits In Two

The 1848 race will be the third and final campaign for the abolitionist Liberty Party.

Its roots trace back to 1839 and the schism within the movement between the Boston-based followers of Lloyd Garrison and the New Yorkers, drawn to the philanthropists, Gerritt Smith and the Tappan brothers, and the Cincinnati journalist, James Birney.

Both groups share the same ends — immediate emancipation and full citizenship for all who remain enslaved – but differ on the means.

The Garrisonians refuse to be drawn into the political arena, arguing that the Constitution and the DC office holders have kept the Africans in chains, and that change will occur only through appealing directly to the good will of the public. They point to the steady progress made by their Anti-Slavery Societies and local lecture tours to support their convictions.

In 1846 Garrison labels the Mexican War “the greatest crime of our age” and campaigns against it. He calls the 1846 Wilmot Proviso a “landmark of anti-slavery resistance,” and in the Fall of 1847, lectures to some 20,000 people across fifteen towns, frequently referring to the Union as “a sinful abomination.” He also burns the U.S. Constitution as a public protest.

But his inflammatory rhetoric and anti-political posture is gradually costing him some support, including that of his long-time protégé, Frederick Douglass. In 1847 Douglas decides to start up his own abolition paper, The North Star, in 1847, without first informing Garrison. From then on their relationship grows distant.

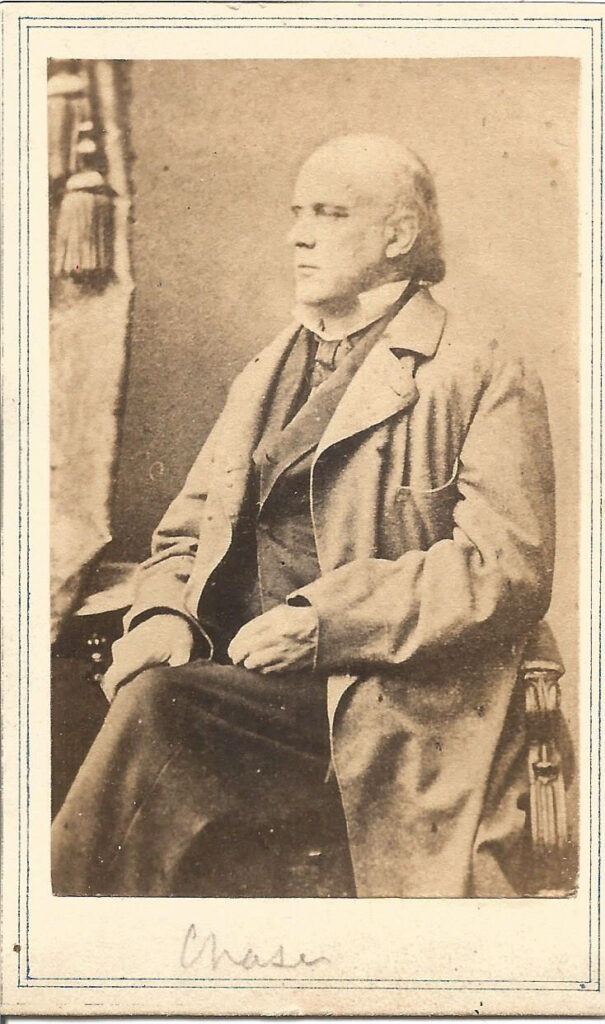

Others, like the strategist, Salmon Chase, simply conclude that Garrison’s strategy is naïve, and that the only realistic path to ending slavery will be to undermine its support in Congress through new legislation. The Liberty Party is born out of this belief in 1840.

Its election performance, however, proves anemic. In 1840, James Birney tops the ticket and receives only 7,000 votes nationally. In 1844 he is again nominated, garnering 62,000 votes or 2% of the ballots cast.

These results provoke an internal split between the Gerritt Smith faction and the Salmon Chase faction, which surfaces at the party convention held in Buffalo on October 20, 1847.

The politically astute Chase is impressed by the anti-slavery traction evident in the congressional votes cast on the Wilmot Proviso, and argues that the Liberty Party would be better off in the short run by fighting the westward spread of slavery rather than by focusing exclusively on total abolition now.

The majority of the delegates line up behind this tactical shift, and nominate the vocal anti-slavery Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire over his one competitor, Gerritt Smith, on the first and only ballot.

Initial Vote Of Liberty Party (1847)

| Candidate | Votes |

| John P. Hale | 103 |

| Gerritt Smith | 41 |

When Smith learns of this outcome, he claims that the party has been hijacked by moderates who would forfeit the abolition crusade for a few more political votes.

His response is to hold a convention of his own on June 2, 1848 in Rochester, New York, where his loyalists back him for President and Presbyterian minister Charles C. Foote of Michigan as Vice-President.