Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 104: The Creole Slave Rebellion Leads To Diplomatic And Congressional Conflicts

November 7, 1841 – April 16, 1842

Britain Free Mutinous American Slaves From The Brig Creole

Three weeks after the Prigg decision, another slavery-related controversy is played out in the U.S. House.

This one is reminiscent of the 1839 Amistad affair, again involving a bloody revolt aboard a slave ship.

In this case the vessel is the brig Creole, owned by a Richmond firm, and transporting 135 slaves from Virginia to the auction market in New Orleans.

On November 7, 1841, an open hatch allows a band of nineteen captives to come on deck and overpower the ten-man crew, severely wounding the captain, Robert Ensor, and stabbing a slave dealer, John Hewell, to death. During the melee, several others are hurt, including a slave who subsequently dies.

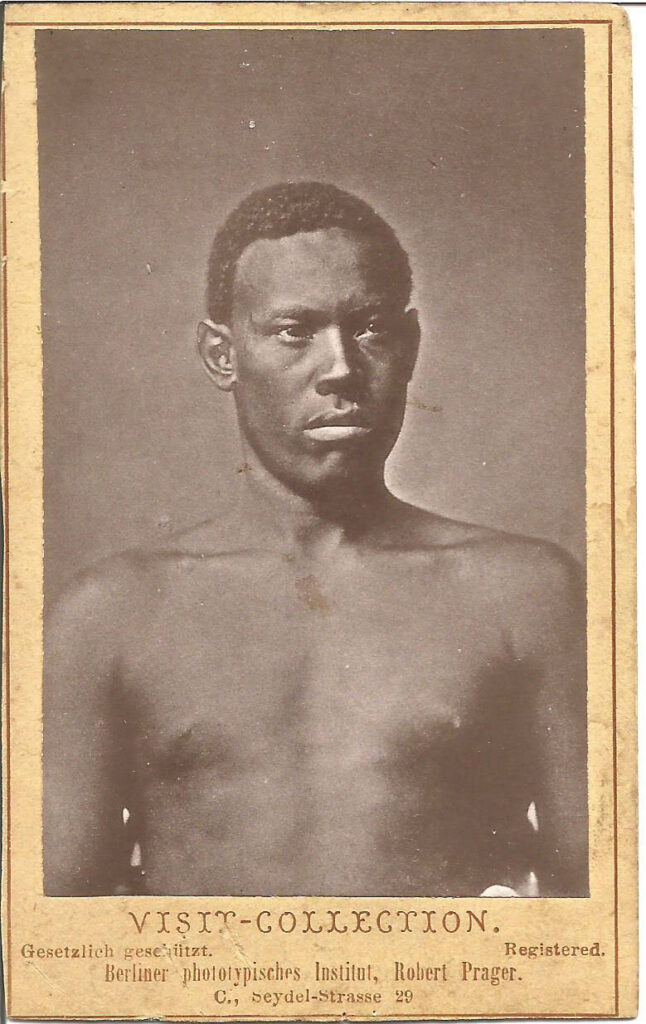

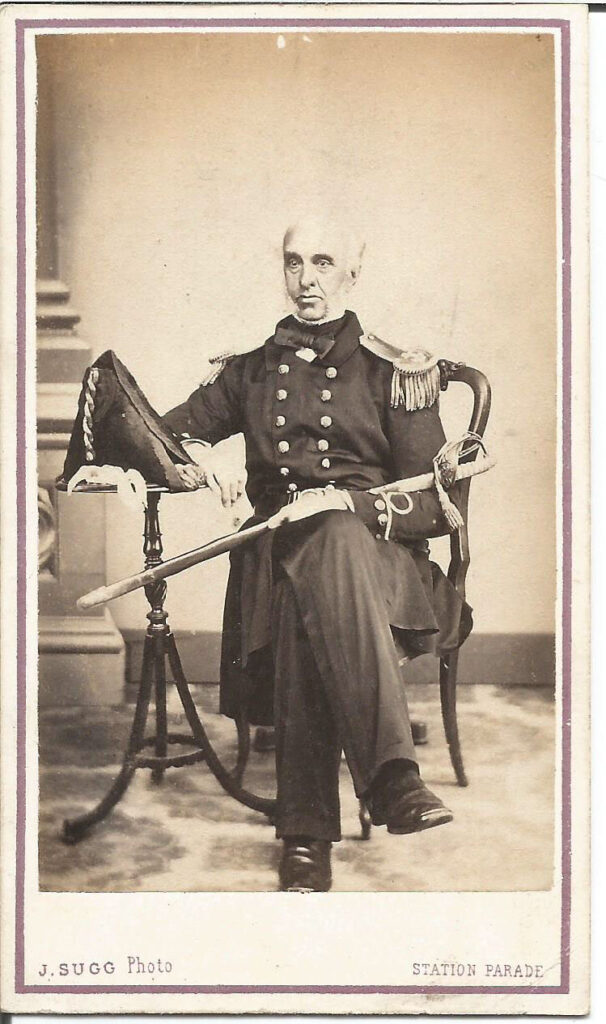

The leader of the rebels is twenty-five year old Madison Washington, a former run-away to Canada, who had been recaptured in Virginia after coming back to retrieve his wife. Once in control of Creole, he orders the helmsman to sail east toward the free colony of Liberia, but alters course because the ship lacks the necessary provisions. Instead he turns south and, on November 9, arrives at Nassau, a British-owned island in the Bahamas, where slavery has been banned since 1834. When the American Counsel, John Bacon, learns of the incident, he assembles a contingent of sailors to board the ship and return it to a U.S. port. The British Governor General, Sir Francis Coburn, who fought in the War of 1812, learns of Bacon’s plan and responds by sending local boats to surround the Creole in port.

Two days later, on November 14, Coburn finishes an investigation of the rebellion and announces his verdict. Nineteen of the slaves are to be held for possible trial as “pirates,” while the remaining 116 blacks are immediately free to depart on their own.

As a further snub to American slave laws, British authorities subsequently conclude that they have no right to try Americans in their courts, and that there are no “extradition treaties” in place to send Madison Washington and the other rebels to the States. On April 16, 1842, the charges of “piracy” are dropped and all are officially released from custody.

Madison Washington vanishes from history at that moment, only to be remembered and romanticized in the 1852 novella, The Heroic Slave, written by Frederick Douglass.

The Creole outcome sets off a diplomatic firestorm between the United States and British diplomats, as well as between Southerners and the small band of vocal anti-slavery voices in Congress.

March 23, 1842

Abolitionist Joshua Giddings Is Censured By The House

The Congressional conflict is sparked by the 75 year old ex-President, John Quincy Adams, the first and still foremost abolitionist in Washington, since rejoining the House in 1833.

Ten weeks have passed since the initial release of the Creole slaves in Nassau, and Adams is on the House floor reading a series of “petitions” from his local constituents, again in clear violation of the 1836 “Gag Order.” These range from a demand to dissolve the Union in light of the Prigg fugitive slave decision, to censuring John Bacon, the American Counsel in Bahama, for trying to interfere in the Creole incident.

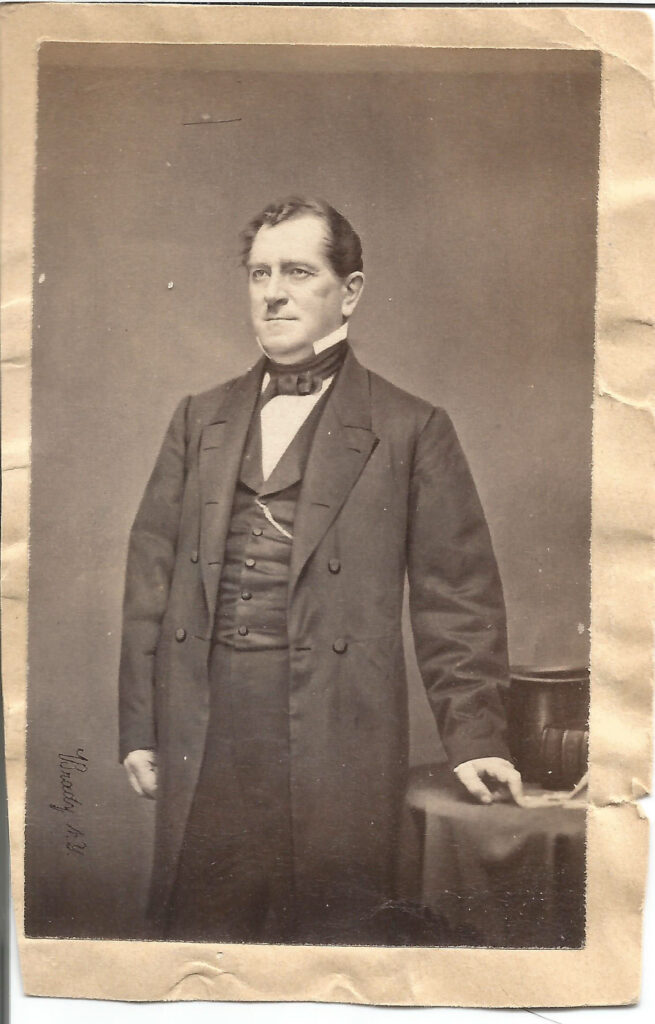

When Adams refuses to relinquish the floor, Representative Henry Wise of Virginia moves, on January 25, 1842, to censure him for “plotting with Britain to end slavery in America.” After cooler heads prevail on behalf of the ex-President, southerners turn their fire on an easier target, Joshua Giddings, who also weighs into the Creole case.

On March 21 the Ohio abolitionist presents a nine part argument which asserts that the minute the Creole slaves left jurisdictional waters off Virginia, their status was no longer determined by state law.

When a ship belonging to the citizens of a state leaves the waters of that state, and enters upon the high seas, the persons on board cease to be subject to the slave laws of that state and are governed by the law of the United States.

This interpretation mirrors the “once free, forever free” view argued by Associate Justice John McLean’s in the Prigg ruling.

But Giddings goes further, saying that slavery violates “natural law” which supersedes municipal law.

Slavery is an abridgement of the natural rights of man (which) can exist only by force of positive municipal law.

Giddings’ argument is much more threatening to the South than was Adams’ in the Amistad case, one year earlier. There the slaves were owned by foreigners and found to be Africans by origin, a clear violation of the 1808 ban on international trading. Here the Creole slaves are born in America and owned by American citizens.

The Southerners pounce immediately on Giddings.

The only laws that govern the Creole, they say, are the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Act – both declaring that owners are free to transport their human “property” into “Free States” without changing their status as slaves.

They pursue a formal “motion to censure” – first, for “introducing an anti-slavery resolution deemed to be incendiary,” and second, for “upsetting delicate treaty negotiations” between the U.S. and Britain focused on settling the Maine-Canada border disputes.

Giddings is given no chance to defend himself and becomes only the second member in House history to be condemned to this degree. After the vote he responds by rising from his chair, walking to JQ Adams desk to shake his hand, and resigning.

This flexing of Southern power is, however, short-lived. Six weeks after exiting the House, a special election in Ohio returns Giddings to the chamber by a vote of 7,469 to 383.