Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 218: The “Mountain Meadow Massacre” Further Inflames Anti-Mormon Sentiment

Late Summer 1857

California Bound Emigrants Pass Into Mormon Utah Amidst Fear Of A Federal Invasion

The tension surrounding the impending arrival of a new Governor backed by U.S. troops contributes to one of the low points in the history of the Mormon Church — a massacre of innocent civilians, perpetrated by religious zealots who attempt, unsuccessfully, to cover up their crime.

The civilians come from northwestern Arkansas and are on their way to resettling in California. They include several groups of travelers who form one wagon train for ease and safety. It is cast as the “Baker-Fancher Party,” and includes 137 men, women, children, cattle and supplies. Together they head west along the old Cherokee Trail, which takes them through the South Pass and into the Utah Territory by late summer.

They stop at Salt Lake City at the height of fear over a full-scale invasion by the federal army. This fear is further inflamed by Brigham Young, whose sermons at the time remind them of their special status as God’s chosen people, distinct from the “Gentiles” (those living without the Gospel) who continue to threaten their faith. To protect the Church, Young declares martial law across the territory.

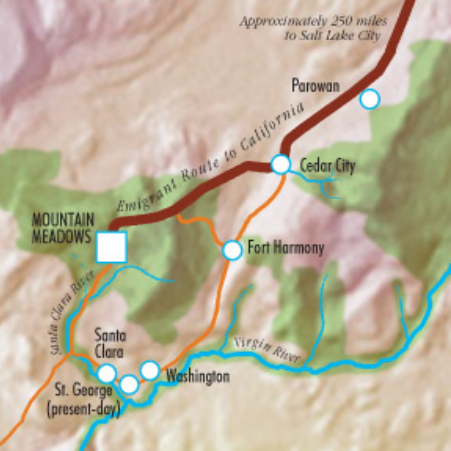

Thus when the Fancher party appears, they are viewed as hostile intruders, and their requests for shelter and supplies are denied in peremptory fashion at Salt Lake. The dismayed travelers are sent on their way, heading south along the Spanish Trail.

After a two-week journey covering some 250 miles, the party stops very briefly at the Mormon town of Cedar City, Utah. Once there, some momentary hostilities occur between the residents and the emigrants that provoke the tragedy that follows. The true nature of these conflicts will never be known, but accusations involve slurs directed at the Mormon founder, Joseph Smith, and accusations that local wells had been poisoned.

Whatever the cause, a band of Cedar City locals are so incensed that they seek permission from Mayor Isaac Haight to call out the militia to pursue and arrest the emigrants. Despite Mayor Haight’s initial veto, those most outraged decide to proceed on their own.

Their leader is 46-year old John D. Lee, an Illinois native, friend of Joseph Smith, adopted son of Brigham Young, and father of some sixty-seven children by his nineteen wives. Lee is also an Indian agent, a member of the Council of 50 church elders, and a Mormon militia captain, headquartered at Fort Harmony.

His plan for revenge lies in convincing his contacts among the Paiute Tribe to attack the wagon train, inflict some casualties and register that as a warning to any future “outsiders” passing through Utah. The typically peaceful Paiutes balk at the idea before Lee promises them plunder and ongoing support from the Mormon community. He also says that several Mormons will dress up as natives and join in the skirmishing.

After the Paiutes agree, Lee brings the plan back to Mayor Haight and the Mormon council in Cedar City. They are apparently alarmed by the idea, ask if Brigham Young has been engaged, and want Lee to stand down until further directions are received. A messenger is dispatched on September 6 to Salt Lake City to hear from Young.

But one day later a premature attack takes place that will leave the entire situation spinning out of control.

September 7, 1857

Mormons Commit Cold Blooded Murders Of Men, Women And Children

Since leaving Cedar City, the “Baker-Fancher Train” rolls another fifty miles south, coming to a halt at Mountain Meadows, Utah, a well-known stop-over point which offers them ample water and grazing land.

On September 7, 1858, their respite is suddenly interrupted in an attack launched by Paiute tribesmen and some of Lee’s militiamen dressed up as Indians. Several party members die and others are wounded in this assault.

By sundown, the travelers literally circle their wagons to defend themselves from what becomes a five day siege.

While this plays out, two emigrants who have ventured outside the lines are also attacked, this time by Mormons not disguised in tribal gear. One dies on the spot, but the other escapes back to the wagon train and reports on the Mormon involvement. The effect of this knowledge will be to put all of the emigrants at risk.

Commander Lee is now in a bind. The fight is under way without approval from his superiors. Emigrants have been killed, and those remaining alive are aware of the Mormon involvement. He returns to the Cedar City council, fills in both his superior in the militia, William Dame, and Mayor Haight on the latest events, and learns that no word is back yet from Young. Here the story gets murkier, but Lee exits with a belief that he has tacit approval from Haight and Dame to finish the job and cover it all up.

He returns to Mountain Meadow, recruits twenty-five or so militiamen, and designs a plot to penetrate the defense perimeter around the emigrant’s camp. On September 11, 1857 Lee appears under a flag of truce, offering to escort the Arkansans to safety. Conditions inside the siege are evidently desperate enough that the offer is accepted.

Lee herds the smallest children into a wagon and the wounded into another. They exit first, followed on foot by women, and then men and boys, each of them closely guard by militiamen.

They march about a mile to a pre-planned killing ground. Once there the Mormons begin their slaughter, aided to some extent by a few Paiutes.

Most of the men are shot in the head, while the women, older children and wounded are either stabbed or clubbed to death. A total of 120 die on the spot, and are buried in shallow graves. The only survivors are 17 children under seven year’s old, deemed too small to ever testify about the murders. They are placed in Mormon homes and will remain there until repatriated later to Arkansas by US army troops. The substantial possessions of the dead are divided between John Lee, his militiamen and some of the Paiutes, with the remainder auctioned off to the public.

From there, attempts to cover up the crime continue. A purported letter from Salt Lake City dated one day before the massacre quotes Brigham Young as ordering the Mormons to “not interfere…to let them go in peace…ever remembering that God rules.” Relatives of the Baker Fancher party in Arkansas and California are informed that the train is ‘lost” – and this story stands until May 1859 when a US Army contingent under Major James Carleton finds human remains at Mountain Meadow, reburies what is left, and opens an investigation.

Accusations follow that Young was involved from the beginning, but he says that the Paiutes acted entirely alone.

Carleton disagrees, and in March 1859, John Lee, Isaac Haight and one other man are indicted by a Utah judge, but all elude arrest.

The national press pick up on the story, and Harper’s Weekly recaps the details in its August 13, 1859 edition, which includes a woodcut rendition of the massacre site and adds to the public ill will directed at the Mormons.

That, however, ends the inquiry into the massacre for over a decade, until well after the end of the Civil War.

In 1870, renewed calls for justice force Young to banish Lee and Haight from the church. Lee is arrested and tried first in 1875, where he is acquitted, and again 1876, where found guilty and sentenced to death.

On March 23, 1877, John Lee is executed by a Mormon firing squad at the site of the Meadow Mountain Massacre. This represents the only punishment ever meted out in the incident.