Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 238: Wisconsin Tries To Defy The U.S. Supreme Court On A Run-away Slave Case

March 10, 1854

A Mob Frees A Fugitive Slave Held In Wisconsin And The Instigator Is Arrested

In 1859, after several years of stonewalling, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin finally turns over documents requested by the U.S. Supreme Court to rule on a contentious run-away slave case.

At issue is the fate of Sherman Booth, who plays a leading role on March 10, 1854, in the unlawful escape from custody of a fugitive slave named Joshua Glover.

Booth is a native of New York who, while studying at Yale University, is hired to teach English to slaves from the Spanish ship Armistead as they await a trial in Connecticut that will free them. He is so moved by this experience that he founds an abolitionist newspaper and helps to organize the state’s Liberty Party before graduating in 1841. In 1848 he moves west to Racine, Wisconsin, and starts up the Wisconsin Freedman paper in nearby Milwaukee.

His editorial fight against slavery turns to action on March 10, 1854, when Joshua Glover, a run away from Missouri, is arrested in a Racine barn by a U.S. Marshal and his master, one Bennami Garland. When Glover is jailed, Booth organizes a protest rally which eventually turns into a mob that frees him and begins his escape to freedom in Canada.

While Booth does not participate in the assault, he encourages it and then boldly announces in his paper that the “Fugitive Slave Act has been repealed in Wisconsin.”

June 7, 1854

The Wisconsin Supreme Court Frees Booth And Declares The Fugitive Slave Act Unconstitutional

Booth is arrested and brazenly admits to his involvement.

When bail of $2,000 is set by U.S. Commissioner Winfield Smith, his supporters raise the funds and, once free, he fires back at the government in a series of editorials and a call for a statewide anti-slavery convention to be held in the capital of Madison on July 21, 1854.

His lawyers then file a writ of habeas corpus with the Wisconsin Supreme Court to force a trial of his case. The result in Abelman v Booth is an acquittal and an opinion written by Associate Justice Abram D. Smith which labels the Fugitive Slave Law a “wicked and cruel Enactment” and declares it unconstitutional.

February 3, 1855

A U.S. Supreme Court Injunction Is Defied

With that, the Booth case assumes national visibility, and a federal court issues an order to re arrest him.

On July 19, 1854 the Wisconsin Supreme Court reaffirms his freedom, only to see him taken into custody two days later by federal marshals.

A trial follows in a U.S. District Court, where the judge orders the jury to ignore all pleas about the “morality of the law” itself. He is convicted and jailed.

Booth again appeals to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and on February 3, 1855, it again finds that the Fugitive Slave Act is unconstitutional and, in turn, releases him from jail.

As soon as the U.S. Supreme Court hears that Wisconsin is ignoring a federal law passed by Congress, it demands to hear the case.

But the Wisconsin Supreme Court frustrates this demand by refusing to send the required case documents to Washington.

March 7, 1860

The U.S. Supreme Court Prevails But Booth Eventually Gains His Freedom

The open resistance in Wisconsin continues over four years, into 1859. In the interim, a separate court case in July 1855 results in Booth being required to pay $1,000 to Joshua Glover’s master for the loss of his slave.

The rest of the story involves many twists and turns.

After finally receiving the needed documentation, and hearing the case against Booth, the U.S. Supreme Court reverses the prior ruling. The opinion, written by Chief Justice Roger Taney on March 7, 1860, says that a state court has no right to file for habeas corpus on behalf of a federal prisoner. Moreover, it has no authority to declare a law passed by Congress unconstitutional.

Booth is soon back in custody – this time in a federal custom house jail in Milwaukee. To add to his woes, he is also accused of raping a fourteen year old girl, a charge that goes unproven but damages his reputation among some prior supporters.

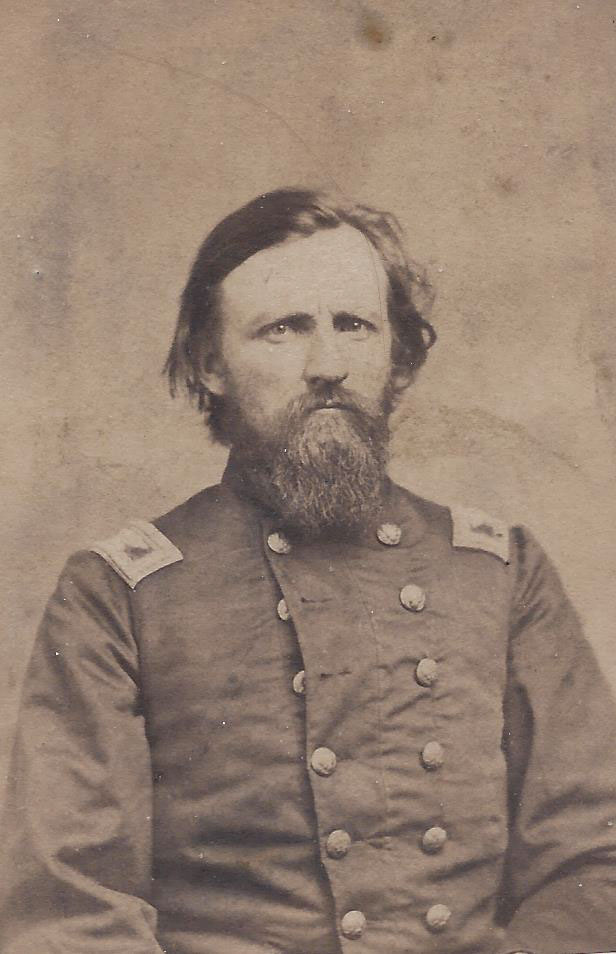

But Sherman Booth remains undaunted. He addresses a “freedom rally” from his cell on July 4, 1860, and less than a month later, on August 1, a ninth attempt to free him by force succeeds. He flees to Waupun, Wisconsin, where he is welcomed ironically by the warden of the state penitentiary there, one Hans Christian Heg, who will later become a war hero, dying in action at the Battle of Chickamauga.

While Booth is re-captured on October 8, 1860, the federal will to punish him has dampened, and Buchanan finally agrees to free him for good. He returns to a career in journalism and lecturing against slavery. His final brush with the law happens in 1865 when he encourages a black man named Ezekiel Gillespie to vote – an act which prompts the Wisconsin Supreme Court to approve negro suffrage in the state.