Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

Chapter 70: Britain Abolishes Slavery

1772-1791

Opposition To Slavery Gradually Mounts In Britain

Britain’s move away from slavery spans roughly a sixty-year period –beginning in 1772 with a King’s Bench ruling in Somerset v Stewart that “chattel slavery was unsupported in English Common Law,” at least in England and Wales.

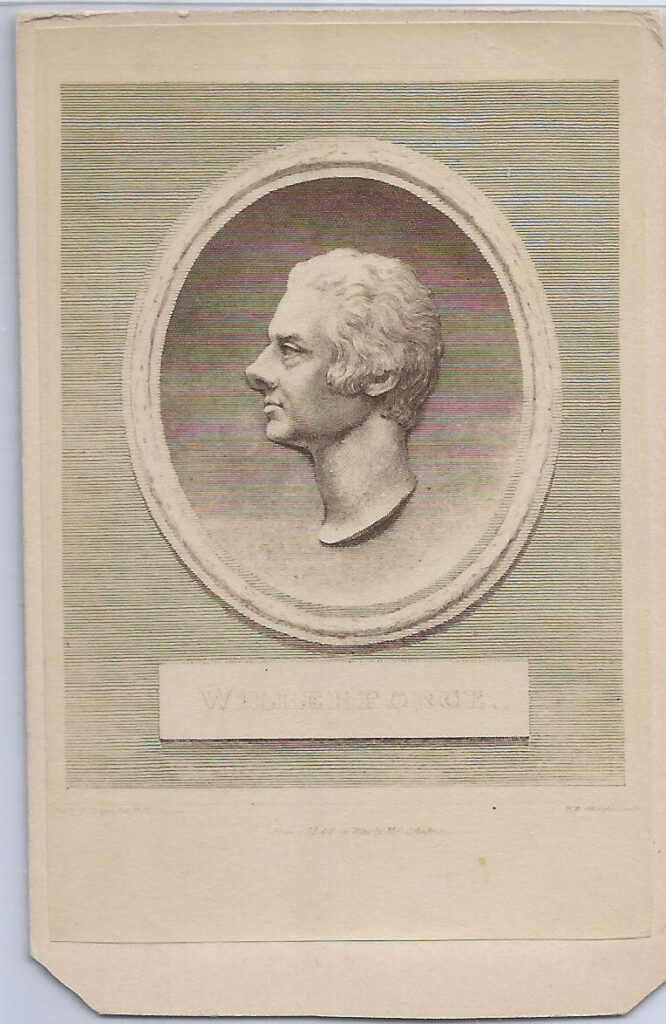

From there the abolition cause is taken up by William Wilberforce, born in 1759, the son of a wealthy merchant, who parties his way through Cambridge University before entering beginning a 45-year career in Parliament in 1780.

Wilberforce is the archetypal “good fellow well met” in his early youth, but then appears to undergo a spiritual conversion around 1785 while touring Europe with a friend. He starts reading the Bible on a daily basis, reflects on the excesses of his life to date, and seeks spiritual guidance from John Newton, an Evangelical minister in the Anglican Church. Newton counsels him to remain in Parliament, but devote himself to promoting Christian causes.

In 1787 Wilberforce bands together with Thomas Clarkson, who has studied for the Anglican ministry, and written essays opposing slavery before becoming a founder of the “Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.”

Wilberforce and Clarkson, together with Congregationalist minister Dr. Thomas Binney, bring their first anti-slavery bills to Parliament in 1791, and these lead to the end of slave trading in 1807.

But the move to full emancipation takes 30 more years, as opponents argue that Africans are sub-human and actually benefit from their bondage – a view repeated in antebellum America.

July 26, 1833

The “Slavery Abolition Act” Passes In Parliament

After the 1830 fall of Wellington’s Tory government, the Whigs take power and resume the push for emancipation. Leading the cause are the Prime Minister, Charles Grey, and Henry Brougham, his Lord Chancellor.

Acceptance of the final 1833 Act comes after a petition with 187,000 names is submitted by the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. This influence of women’s groups on abolition (and its first cousin, suffrage) will be repeated in the U.S.

Consistent with British practice, the bill becomes law after the third reading on the floor of Parliament, which occurs on July 26, 1833 – two days after the death of William Wilberforce.

The 1833 Act ends slavery in all British territories with the exception of Ceylon, the Island of St. Helena and provinces controlled by the East India Company (mainly the Indian sub-continent).

Slave-holders are compensated for the emancipation through a special fund of 20 million pounds sterling, an amount that represents almost 40% of the Crown’s annual budget. The actual amount paid out per slave appears to vary widely, but the average may have been around 50 pounds, the equivalent of about $250. Records show that many of the elite families of England are recipients of these pay-outs.

Britain’s abolition of slavery follows on the heels of Canada (1804), Spain (1811) and Mexico (1829). France will follow suit in 1848.

Passage of the 1833 Act becomes a message of hope for the still nascent abolitionist movement in America.