Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 123: The War With Mexico Picks Up Momentum

August 15 – September 21, 1846

Santa Fe Is Captured And The Battle For Monterrey Begins

While the “Bear Flag” land grab is playing out in California during June-July 1846, further U.S. incursions into Mexico are under way.

On August 15, 1846, General Stephen Kearny captures Sante Fe, the capital of the province of New Mexico, without firing a shot.

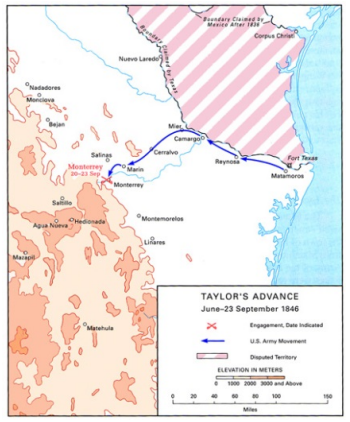

At the same time, General Taylor is heading west at a leisurely pace in pursuit of the Mexican army, which he defeated at Resaca de la Palma back in April.

He will find it in September, holed up at Monterrey, an enclave of 10,000 inhabitants, and the capital of Nuevo Leone province.

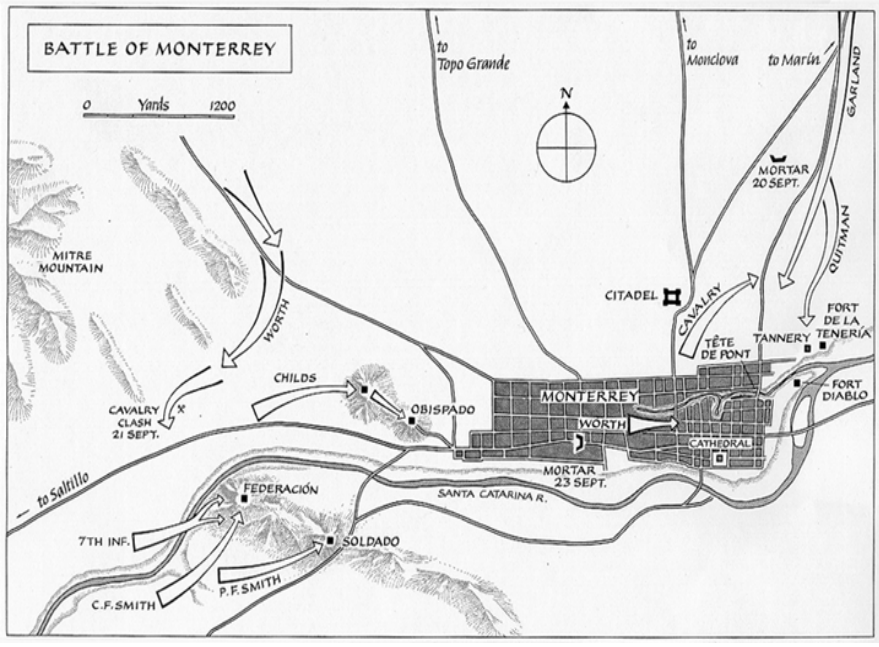

The city sits in a valley surrounded on two sides by the 4,000 foot peaks of the Mitre mountains, with the Santa Catarina River running along its eastern and southern flanks. Its location along the main road through the mountains toward Saltillo makes it strategically important to the westward advance of Zachary Taylor’s army — and knowing this, General Pedro Ampudia, who has now replaced Avista, decides to defend Monterrey.

In addition to its natural advantages in terrain, Monterrey is also well protected by a series of redoubts and stone buildings that dot the roads in from the northeast. General Ampudia concentrates his 9,000 troops across these fortifications, and confidently awaits the Americans.

Taylor, however, pauses for several weeks after his opening victories, and it is not until June 12 that he sends Ben McCulloch and his Texas Rangers out to scout the whereabouts of the Mexican army. When Taylor learns they are dug in at Monterrey, he sets three divisions and some 6600 troops in motion under Generals William Worth, David Twiggs, and John Quitman. They arrive in early September and begin to plan their strategy.

Lacking heavy artillery, Taylor knows that he must assault rather than siege Monterrey. After studying the ground, he settles on a daring two-prong attack. Quitman and Twiggs will send the bulk of the army headlong at the heavily defended fortresses north and east of the city. Worth and 1700 men will swing west 7 miles under cover and arrive in the enemy’s rear on the Saltillo road, cutting off the Mexican’s supply and escape routes. If practicable, Worth will then launch a surprise attack against the more lightly defended western edge of the city. On September 20, Worth’s flanking movement secures the Saltillo road, after a brief cavalry battle. Mexico’s northern army is now effectively trapped in Monterrey as Taylor’s assault begins on September 21.

Colonel John Garland, leading Twigg’s division, opens the battle against the eastern fortifications, with support from Mississippi and Tennessee units under Quitman and Colonel Jefferson Davis. They capture Fort de al Teneria and the bridge leading over the river to Ft. Diablo. Ohio troops under General Butler join the attack on Diablo, but it is successfully defended throughout the day by General Ampudia’s forces. After ferocious street-to-street combat the Americans have gained a solid toehold on the eastern side of the city by nightfall.

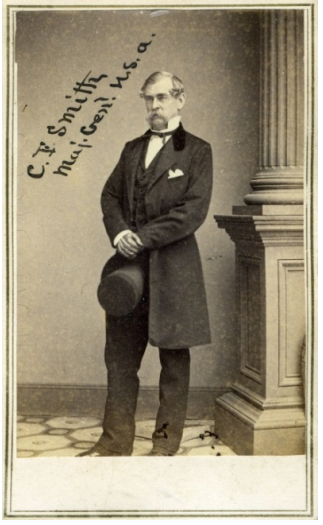

Progress to the west is even greater, with the hero of the day being Captain Charles F. Smith, who leads his four companies up a spur of Mt. Mitre known as Federacion Hill, drives off the Mexican defenders, and turns decisive artillery fire down on the city. As the first day of battle to the west ends, General Worth is poised to invade Monterrey from the west.

September 22-24, 1846

Monterrey Falls To Taylor

Overnight, General Ampudia decides to consolidate his two wings in the center of the city. He abandons Ft. Diablo, and draws back all his forces to the Cathedral and Central Plaza area, for a last stand.

At daybreak on September 23, General Quitman and a force of Texas Rangers resume their advance on Ft. Diablo and, finding it empty, race past it into the city, with shouts of “Alamo and Goliad” ringing through the streets. Taylor, however, is unaware of their breakthrough, and orders them to hold for the moment.

Meanwhile, General Worth hears the early sounds of battle and sends his troops forward to capture the western end of the city and envelop the remaining Mexicans. They quickly take the Bishop’s Palace outpost and begin house to house fighting.

By nightfall Worth has reached to within one block of the Plaza, and is in contact with Quitman and his troops, now nearby. The fates of the Mexican army and of the city of Monterrey are sealed – and General Ampudia knows it. On the night of September 23, he approaches General Worth for “terms of surrender.”

The agreement he finally works out with General Taylor is so stunning in its generosity that when word filters back to Washington, Polk wants to relieve Taylor of his command, despite the victory.

In return for ceding all public property in Monterrey to the Americans, Ampudia is allowed to evacuate his army, along with its small arms, within seven days, and any further conflict is suspended for the next six weeks.

While Taylor has lost 500 soldiers in the battle, to over 1,000 for the enemy, he is evidently so convinced that the Mexican army is defeated once and for all that he allows it to walk off the field in another retreat west.

Five months later he will realize that this calculation was not quite right.

Sidebar: Milestones In Taylor’s Invasion Through Texas

Taylor’s 190 Mile Drive From Matamoros To Monterrey

| Date | Events |

| April 24, 1846 | Taylor attacked along the Rio Grande |

| May 9 | Taylor victory at Resaca de la Palma |

| May 13 | Official declaration of war |

| May 18 | Taylor occupies Matamoros |

| June – July | California taken in Bear Flag Revolt |

| August 15 | Kearney secures New Mexico |

| September 24 | Taylor victory at Monterrey |

Winter 1846

Polk’s Cabinet Debates War Strategy And Commanders

Ever since General Zachary Taylor’s troops are first attacked along the Rio Grande on April 25, 1846, the conflict with Mexico has all gone the American’s way. His northern army, under Kearney, has planted the American flag from Santa Fe through California, and Taylor’s central force has driven inland to capture Monterrey.

The only thing lacking so far is a formal capitulation by the Mexican government and a treaty resolving final ownership of the conquered lands. Various emissaries from Mexico hint at this resolution, but so far it remains simply a wish.

So the question becomes one of what it will take to bring the war to closure. This topic is hotly debated within Polk’s cabinet. As usual, the President is clear about his preference – to expand the invasion until the enemy gives in.

His cabinet, led by the ever bothersome Secretary of State, James Buchanan, and the War Minister, William Marcy, object to his proposal for three reasons:

- A broader invasion will extend the fighting and produce more agitation in Congress;

- They do not believe that General Winfield Scott is up to the task of leading the troops; and

- Both Scott and Taylor are Whigs who might run for president in 1848.

Polk floats out the possibility of promoting Senator Benton of Missouri to Lieutenant General, ranking Scott and taking overall command in the field, but he backs off when others resist. It’s now clear that whatever future course the war takes, Scott will remain the lead general.

As the cabinet ponders options to end the war, critics begin to assert that Polk’s hidden intent is to conquer all of Mexico, absorb it into the United States, and reinstitute slavery, banned there in 1829.

Polk flatly rejects these charges and insists that all future decisions about slavery in new territory acquired from the war will be left to the will of the settlers, as they write their state constitutions.

But this assurance isn’t enough for the skeptics in congress – who again wave the Wilmot proviso in the face of the President and the Southerners.

Winter 1846

General Scott Announces His Plan

(1786-1866)

As political controversies over the war swirl about Washington, all eyes look toward the 61 year old General Winfield Scott for his plan to resolve the conflict.

Scott is a Southerner by birth and grows up on a Petersburg, Virginia plantation. He briefly attends the College of William & Mary, studies and practices law, then enlists in the Virginia militia. He comes to fame in the War of 1812, in the back and forth battles around Lake Ontario. He is wounded twice in the fighting, first as a Colonel, while capturing Ft. George, and later as a Brigadier General, near Niagara Falls at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. For his heroism, he is made a Brevet Major General at age 27. But the bullet wound to his left shoulder leaves him with a partially paralyzed arm, and he is unable to resume field duty.

After the 1812 War, Scott studies military strategy in France, writes various military manuals on drilling and tactics, and continues to advance his career. President Jackson calls on him to help put down the Nullification threat in 1832, to fight the Seminoles in 1836, to relocate the Cherokees in 1838. He becomes the ranking officer in the army in 1845, as a full Major General.

Scott is an enormous man, standing 6’5” and weighing over 250 lbs. His manner is imperious; he is a stickler for discipline; and he constantly decks himself out in elaborate uniforms. Hence the nickname, “Old Fuss and Feathers.” Polk regards him in 1847 as a man filled with ‘arrogance and inordinate vanity.”

Nevertheless, the General finally steps forward with a plan to win the war. He will assemble and personally lead an invasion force of some 14,000 troops, capture the port city of Veracruz, then march overland to overwhelm and occupy the capital of Mexico City.

Polk reluctantly adopts the plan, and orders go out for Taylor to hold his position at Monterrey while detaching the bulk of his army to join up with Scott’s invasion force.

The fate of the President’s war now rest in the hands of two Whig Generals, both of whom he distrusts as military commanders and as potential political opponents of his Democratic Party.