Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 171: Presidential Candidates Chosen Amidst Deep Party Divisions

Summer 1852

Several Key Whigs Defect To The New Free Soil And Unionist Parties

As Millard Fillmore’s term nears an end, the Whigs are again left frustrated by the performance of an “accidental” successor to their real choice as President. First it was the “turn-coat,” John Tyler, succeeding General Harrison after one month, in 1841; then the “dough-face,” Fillmore, serving the final 32 months of General Taylor’s presidency, as of 1850.

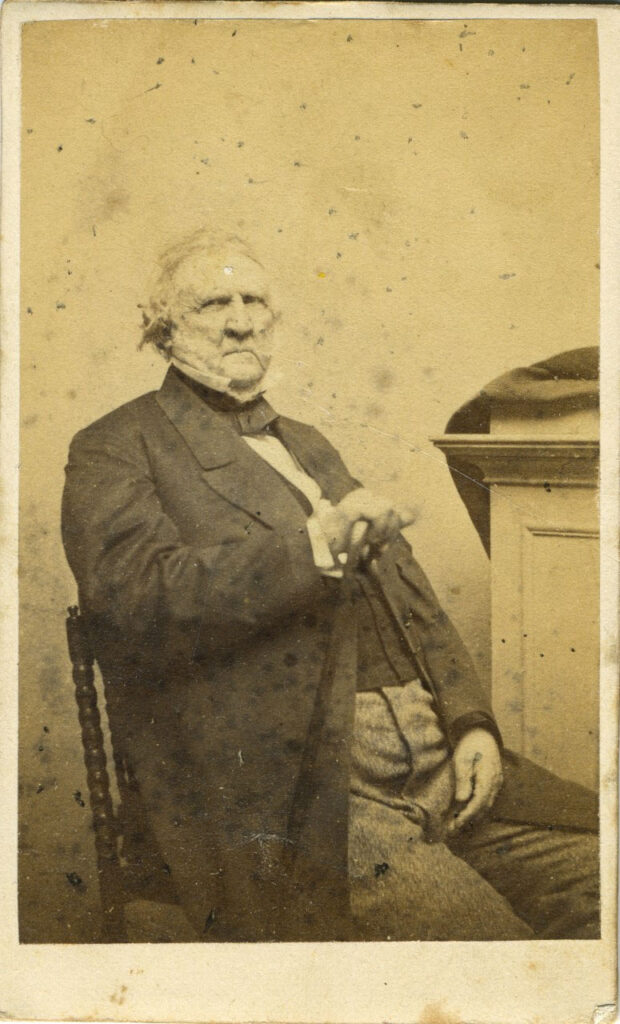

On top of this, the Whigs suffer major set-backs in the House elections of 1850-51, and are about to lose the two leading pillars of their party. One is their founder, Henry Clay, who has left Washington for his plantation in Ashland, about to die from tuberculosis in June 1852; the other, Daniel Webster, leader of the New England faction, who will pass four months later, in October.

It has been Clay’s “American System” that has held the party together since it first coalesced in 1836. Its tenets have included a strong federal government to be funded by higher tariffs – with revenue spent largely on infrastructure projects, to build the economy and to link the new western states into the east.

Whig cohesion has also rested on dedication to preserving the Union through compromises on often divisive issues like tariff rates and the future of slavery. In the 1840’s most Whig leaders initially oppose the Texas annexation and the Mexican War for fear that the addition of new land will re-open sectional conflicts – with the South demanding an expansion of slavery and the North intent on preserving the territory for whites only. That fear proves to be the case.

Zachary Taylor tries to end this threat once and for all by embracing a Wilmot-like ban on slavery across the entire Mexican Cession. When Fillmore abandons that course following Taylor’s death, the Whig coalition continues to come apart at the seams over the issue.

The initial schism materializes in 1848 in Massachusetts, where three younger Whigs – Charles Francis Adams, Henry Wilson and Charles Summer – abandon Daniel Webster, Edward Everett and “the state establishment” to declare their “conscientious objection” to slavery. These three, along with the Ohio jurist, John McLean, Salmon Chase and John Hale find their new home in the Free Soil Party, a catch-all for dissident Whigs and Democrats who oppose the spread of slavery, either on moral or purely racist grounds.

In 1852, it is the Southern Whigs turn to flee the base.

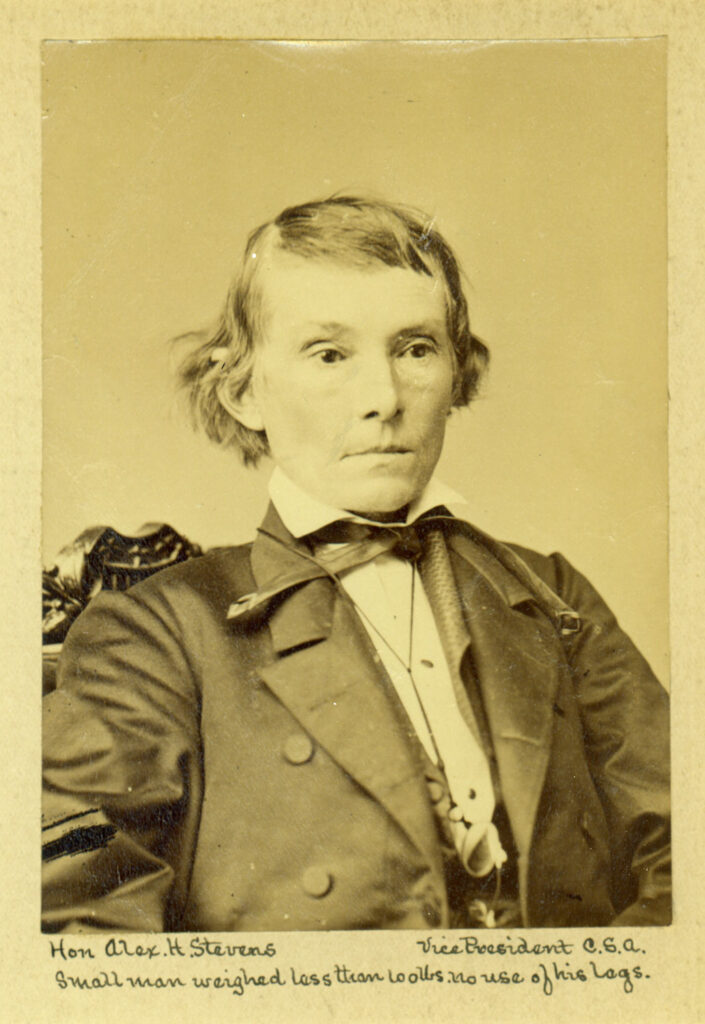

The central defectors here are the two influential Georgians, Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens, and Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, who has served as Taylor’s Attorney General. Together they form the “Unionist Party” to signal their support for the final 1850 Compromise, which the Whigs opposed.

Fracturing Of The Whig Party (1848-52)

| 1844 | 1848 | 1852 |

| Whigs | Core Whigs Conscience Whigs Cotton Whigs | Whigs Free Soilers Unionists |

Together with these departures and the imminent deaths of the two-party “giants,” Clay and Webster, the Whigs head into the 1852 race searching for new leaders and with great trepidation about the likely outcome.

Whig Party Stalwarts And Defectors As Of 1852

| Core Whigs | Age | State | 1844 | 1848 | 1852 |

| Henry Clay | 75 | Ky | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Daniel Webster | 70 | Mass | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Winfield Scott | 66 | Va | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| John Crittenden | 65 | Ky | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Edward Everett | 58 | Mass | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| John Bell | 56 | Tenn | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Edward Bates | 55 | MO | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Rufus Choate | 53 | Mass | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Millard Fillmore | 52 | NY | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Henry Seward | 51 | NY | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| William Graham | 48 | NC | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| William Dayton | 45 | NJ | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| James Pearce | 47 | Md | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Orville Browning | 46 | IL | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Robert Winthrop | 43 | Mass | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Abraham Lincoln | 43 | IL | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Zachariah Chandler | 39 | Mich | Whig | Whig | Whig |

| Whig Party Defectors | |||||

| John McLean | 67 | Ohio | Whig | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Reverdy Johnson | 56 | Md | Whig | Whig | Unionist |

| CF Adams | 45 | Mass | Whig | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Robert Toombs | 42 | Georgia | Whig | Whig | Unionist |

| Cassius Marcellus Clay | 42 | Ky | Whig | Whig | Anti-Slavery |

| Charles Sumner | 41 | Mass | Whig | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Henry Wilson | 40 | Mass | Whig | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Alexander Stephens | 40 | Georgia | Whig | Whig | Unionist |

| George Julian | 35 | Indiana | Whig | Free Soil | Free Soil |

Sidebar: The Fate Of Henry Clay’s Slaves

Henry Clay’s death on June 29, 1852 comes after four decades of public service spent on navigating America through one crisis after another, from the War of 1812 to the 1820 Missouri Compromise, the Nullification crisis of 1832 to the Bank Panic of 1837, the Texas Annexation of 1845 and the subsequent Mexican War, to his 1850 Omnibus Bill aimed at resolving sectional strife over the admission of the western territories to the Union.

As a young man, he is “Prince Hal,” a touch on the wild side, including two duels. But he settles down, studies law, enters politics and founds the Whig Party to combat his bete noir, Andrew Jackson. In turn, he creates the American System to build the infrastructure needed for economic growth; fails in election bids for the Presidency in 1824, 1832 and 1844; and suffers the loss of a son and namesake at the Battle of Buena Vista in a war he had hoped to avoid. All along he is admired by his fellow Whigs, including a young Abraham Lincoln, thirty years his junior.

The issue of slavery haunts his entire time on the national stage. He owns 60 slaves on his Ashland plantation, but is forever guilty about it. He is convinced that the Africans are innately inferior to white men and doubts they could ever be assimilated. Instead they need to be returned home, a goal he sets as co-founder of the American Colonization Society in 1816.

But in 1852, his time has come, and closure is needed on his remaining slaves. His last will sorts them into two groups, those owned before and after 1850. He transfers the former to his wife and sons, with one condition:

In the sale of any, I direct that the members of families shall not be separated without their consent.

His directions for the others are more elaborate and telling.

The issue of all my female slaves, which may be born after the first day of January 1850, shall be free at the respective ages of the males at twenty eight, and of the females at twenty five.

I further…direct that the issue of any of the females, who are so to be entitled to their freedom at the age of twenty five, shall be deemed free from their birth… that they be bound out as apprentices, to learn farming or some useful trade, upon the condition of also being taught to read, to write and to cipher… that the age of twenty one having been attained, they shall be sent to one of the African Colonies. To raise the necessary funds, if they shall not have previously earned them, they must be hired out a sufficient length of time.

I…enjoin my executors and descendants to pay particular attention to the execution of this provision of my will. And if they should sell any of the females who, or whose issue are to be free, I especially desire them to guard carefully the rights of such issue by all suitable stipulations and sanctions in the contract of sale. But I hope that it may not be necessary to sell any such persons who are to be entitled to their freedom, (except) that they may be retained in the possession of some of my descendants.

Clay’s will lays out a path to emancipation and a return to Africa after learning the life skills he thinks they will need to thrive once they are back home. While that much sounds admirable, the terms are hedged in places. Some of his slaves will be retained for his descendants in perpetuity, while the others will have to wait for more than two decades for their freedom. Thus it is a gesture in the right direction, but still far short of the higher order example set by George Washington in his 1799 testament.

Summer 1852

Unity Among The Democrats Is Also Being Tested

In 1852, the hope among Democrats is that the passage of the 1850 Compromise Bill, cleverly engineered and sold by Stephen Douglas, will be sufficient to hold Southern members in line and cure the internal breeches caused by David Wilmot’s Proviso of 1846.

Party unity has been aided by the return of many Northern “Barnburners” who became Free Soilers in 1848 not to oppose slavery, but to seek political revenge for Van Buren’s loss to Polk at the 1844 convention. The “returnees” include both the ex-President and his son.

However, the admission of California as a Free State still rankles many Southern Democrats, as does the failure to secure support for extending the 36’30” Missouri demarcation line from the Mississippi River to the west coast.

Two prominent southerners — Georgia Governor Howell Cobb and Mississippi Senator Henry Foote – signal their displeasure by joining the Unionist movement, which calls for enforcing constitutional sanctions of slavery, while rejecting secession.

Divisions Within The Democratic Party (1848-52)

| 1844 | 1848 | 1852 |

| Democrats | Democrats Free Soilers | Northern Democrats Southern Democrats Free Soilers Unionists |

The challenge at the convention will be to avoid more slippage among the Southern contingent.

Northerners, led by the aging Cass and the youthful Douglas, continue to hold out their “popular sovereignty” as the last best hope to extend slavery to the west. But more and more Southerners fear that the outcome in Congress will go against them in the end. Within this latter group, two factions emerge by 1852.

The radical, minority group comprises the political progeny of John C. Calhoun, Fire-Eaters like Robert Rhett, James Hammond, William Yancey, James Mason and David Atchison, who openly call for secession.

They are off-set by moderates who favor holding both their party and the country together on the hope of electing a new Democrat President – albeit likely a Northerner — who will give in to Southern demands. Included here are two younger leaders in particular, the 44 year old Mexican War hero and ex-Senator from Mississippi, Jefferson Davis, and John C. Breckinridge, son of a famous Kentucky family, at 31 years old, already the head of the Democrat caucus in the U.S. House.

The immediate challenge for these moderate Southerners will be to identify the “right” candidate for the White House in the coming election.

Democrat Party Stalwarts And Defectors As Of 1852

| Core Democrats | Age | State | 1844 | 1848 | 1852 |

| John Calhoun | 70 | SC | Democrat | Democrat | Dead |

| Thomas H Benton | 70 | MO | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Lewis Cass | 70 | Mich | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| William Marcy | 66 | NY | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| William King | 66 | Ala | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| James Buchanan | 61 | Pa | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| James Guthrie | 60 | Ky | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Sam Houston | 59 | Texas | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| John Slidell | 59 | La | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Andrew Butler | 56 | SC | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| James Mason | 54 | Va | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Andrew Donelson | 53 | Tenn | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Daniel Dickinson | 52 | NY | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Robert B. Rhett | 52 | SC | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Lin Boyd | 52 | Ky | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Joseph Lane | 51 | Oregon | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Benj Fitzpatrick | 50 | Ala | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

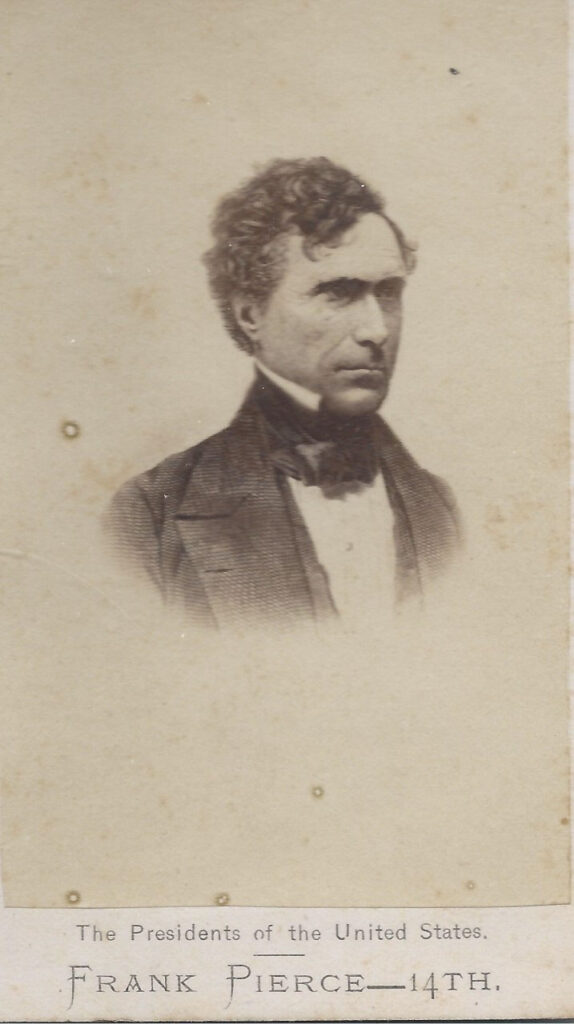

| Franklin Pierce | 48 | NH | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| James Shields | 46 | IL | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| David Atchinson | 45 | MO | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| James Hammond | 45 | SC | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Andrew Johnson | 44 | Tenn | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Jefferson Davis | 44 | Miss | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| RTM Hunter | 43 | Va | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Horatio Seymour | 42 | NY | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Herschel Johnson | 40 | Georgia | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Jesse Bright | 40 | Indiana | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| John McClernand | 40 | Illinois | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Stephen Douglas | 39 | IL | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Albert Brown | 39 | Miss | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Montgomery Blair | 39 | MO | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| John C. Fremont | 39 | Cal | —– | —– | Democrat |

| Louis Wigfall | 36 | Texas | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Ben Butler | 34 | Mass | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| William Yancey | 34 | Ala | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| John Breckinridge | 31 | Ky | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| William P. Miles | 30 | Ala | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| Defectors | |||||

| Martin Van Buren | 70 | NY | Democrat | Free Soil | Democrat |

| Francis Blair Sr | 61 | MO | Democrat | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| John Dix | 54 | NY | Democrat | Free Soil | Democrat |

| Simon Cameron | 53 | Pa | Democrat | Democrat | Know Nothing |

| Gideon Welles | 50 | Conn | Democrat | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Henry Foote | 48 | Miss | Democrat | Democrat | Unionist |

| Preston King | 46 | NY | Democrat | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| John Hale | 46 | NH | Democrat | Independent | Free Soil |

| Hannibal Hamlin | 43 | Maine | Democrat | Democrat | Democrat |

| John Van Buren | 42 | NY | Democrat | Free Soil | Democrat |

| David Wilmot | 38 | Pa | Democrat | Free Soil | Free Soil |

| Howell Cobb | 37 | Georgia | Democrat | Democrat | Unionist |

| Nathaniel Banks | 36 | Mass | Democrat | Democrat | Free Soil |

June 1-5, 1852

The Democrats Need 49 Ballots Before Settling On Franklin Pierce

The Democrats convene on Wednesday, June 1, 1852, to select their presidential nominee. The meeting is held in Baltimore at The Maryland Institute For The Promotion Of Mechanic Arts, and runs for five days.

The arriving delegates are optimistic about their chances. They have regained solid congressional majorities in the mid-term races and are eager to exploit the rupture among the Whigs.

They believe they will succeed if the more moderate Southern Democrats, among them Jeff Davis and John Breckinridge can coalesce with Northern forces around someone who can unify the party. Four men are eager to assume that role.

The most obvious is Lewis Cass of Michigan, proponent of the “popular sovereignty” compromise on slavery, and nominee in 1848 who carried 14 of 29 states, and lost to Taylor by a narrow 163-127 margin in electors. But Cass is now seventy years old and facing the fact that no prior loser has ever come back to win the presidency.

Another old hand is William Marcy, age sixty-six, the long-time leader of the party machine in New York known as the Albany Regency, and more recently Polk’s Secretary of War from 1845-49. His loss to Henry Seward in the 1838 race for governor is, however, a concern, and many consider him a regional, not a national, figure.

A third option is Stephen Douglas whose political career has been meteoric to date. In pushing the 1850 Bill through the Congress, he has demonstrated his ability to achieve regional consensus. Douglas is a Northern man, who owns a sizable plantation in Mississippi and announces that he will favor Robert TM Hunter of Virginia as his running mate. What weighs against the “Little Giant” is his youth (39 years old) and the fact that his supporters overlap with those of his mentor, Cass.

Thus comes the second most obvious contender, sixty-one year old James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. On paper his credentials are pristine. Ten years in the House; Ambassador to Russia; another ten in the Senate; then Polk’s Secretary of State. But lurking around the edges of this track record are “character issues,” some whispered, others said out loud. In an age of rough and tumble masculinity, Andrew Jackson will refer to Buchanan as “Aunt Nancy,” for his delicate mannerisms and affectionate behavior toward a Washington housemate, Senator William King of Alabama. Jackson’s protégé, James Polk, also exhibits frustration with his Secretary of State on multiple occasions, most often around waffling on policy recommendations (Oregon and Mexico expansion) to improve his own presidential prospects. Still, most delegates view Buchanan as the most likely option to Cass, as the voting begins.

On the first ballot, Cass leads Buchanan while falling some 30 votes short of the clear majority needed to win. By the 21st round, Cass fades, with Buchanan and Douglas gaining momentum. The 29th ballot – taken on Friday –finds many Cass supporters switching to Douglas, testing his ability to win the nomination. But this too fails.

Voting Results Through Day 1 (149 Needed To Win)

| Candidate | 1 | 2 | 12 | 21 | 29 |

| Lewis Cass | 116 | 118 | 98 | 60 | 27 |

| James Buchanan | 93 | 95 | 88 | 102 | 98 |

| Stephen Douglas | 20 | 23 | 51 | 64 | 91 |

| William Marcy | 27 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 |

| Others | 40 | 33 | 32 | 44 | 54 |

On Saturday morning comes another upheaval, with Cass making a remarkable comeback on the 34th tally, sourcing votes from both Douglas and Buchanan. But again the pro-Cass faction is unable to find the eighteen additional backers he needs to win.

On the 35th roll-call a new name appears for the first time when Virginia suddenly casts its 15 votes for forty-seven year old Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, who has been out of public office for a decade.

Another twist occurs on the 46th ballot, with William Marcy jumping into the lead for the first time. But like the others, Marcy is unable to tack on more support. By the 48th round the delegates finally realize that none of the original four front-runners are viable, which forces everyone to ponder the “fallbacks” available.

The answer comes on the 49th tally, after James Dobbin, the head of the North Carolina delegation which had backed Buchanan, heralds Pierce for supporting the 1850 Compromise and the Constitution. The result is a stampede to Pierce as the standard bearer for 1852.

Full Voting Results At The 1852 Democratic Convention (149 Needed To Win)

| Candidate | 1 | 2 | 12 | 21 | 29 | 34 | 35 | 46 | 48 | 49 |

| Lewis Cass | 116 | 118 | 98 | 60 | 27 | 130 | 131 | 78 | 72 | 2 |

| James Buchanan | 93 | 95 | 88 | 102 | 98 | 49 | 39 | 28 | 28 | 0 |

| Stephen Douglas | 20 | 23 | 51 | 64 | 91 | 53 | 52 | 32 | 33 | 2 |

| William Marcy | 27 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 33 | 34 | 98 | 89 | 0 |

| Franklin Pierce | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 44 | 55 | 282 |

| Others | 40 | 33 | 32 | 44 | 54 | 31 | 25 | 16 | 19 | 10 |

Unlike James Polk in 1844 – who enjoyed Jackson’s backing prior to the convention – Pierce is a genuine dark horse victor in 1852. He does, however, fit the model that Cass established for Democratic candidates, a Northern man by geography who is willing to bend on slavery to the Southern members of the party. In other words, a “Doughface.”

His nomination demonstrates that while the South can no longer hope to place one of their own in the White House, they can, by holding together, veto any Northerner who is put forward.

As another sop to the South, the exhausted delegates choose Buchanan’s ally, William Butler of Alabama, as Pierce’s running mate. They also adopt a platform that pledges to enforce the 1850 Bill, including the Fugitive Slave Act, and end further agitation over constraints on slavery.

When word of the outcome reaches Pierce, rumor has it that his wife, Jane, faints on the spot.

June 17-20, 1852

A Stalemated Whig Convention Selects Scott On The 53rd Ballot

Twelve days after the Democrats depart the Maryland Institute, the Whigs pour into the same site for a nominating convention also marked by controversy.

An ominous tone hangs over the gathering from the beginning — with Henry Clay, the father of the party, lying on his deathbed in nearby Washington, and the second Whig pillar, Daniel Webster, reeling politically from his March 7 speech supporting the Fugitive Slave Act.

Then there are the losses suffered in the mid-term elections, and the very mixed reactions within the party to their own sitting President. Millard Fillmore was no more than an afterthought at the 1848 convention, and his track record, after being thrust into office by Taylor’s death, has been mediocre. Rumor also has it that after giving Webster, his Secretary of State, a green light to win the nomination in 1852, he has characteristically changed his mind and entered the race. This move apparently galls the crusty Webster who, at seventy, is described as a “poor, decrepit old man,” already suffering from the cirrhosis that will kill him five months hence.

Given these reservations about Fillmore and Webster, a third figure, General Winfield Scott, presents himself as a prominent option. Scott is sixty-six at the time, standing 6’5”, weighing 300 lbs. and fitting Thurlow Weed’s political dictum to ride a military hero to victory. This model worked with Harrison and Taylor, so why not again with Scott.

The first two days of the convention are devoted to administrative matters and the passage of a platform. A Southern version is rejected by a 227-66 margin in favor of a very brief alternative consisting of eight “sentiments.” The first seven reflect traditional Whig doctrines, stated as generalities. The eighth, however, takes a firm stand in support of the 1850 Bill and the Fugitive Slave Act, and an end to sectional “agitation.”

That the series of acts of the Thirty-first Congress,—the act known as the Fugitive Slave Law, included—are received and acquiesced in by the Whig Party of the United States as a settlement in principle and substance, of the dangerous and exciting question which they embrace; and…we will…insist upon their strict enforcement…and we deprecate all further agitation of the question thus settled, as dangerous to our peace; and will discountenance all efforts to..renew such agitation.

Next comes nominations for president, with the first roll call setting the stage for the grinding deadlock to follow. Fillmore leads with 133 votes to Scott’s 131, with Webster trailing far behind. A minor shift occurs on the eighth tally, with Scott moving ahead – but from then on the two front-runners remain stalemated.

Calls to change the rules from a majority to a simple plurality are rejected, and June 19 ends on the 46th ballot, with Scott at 134 votes, Fillmore hanging on to 127, and the delegates scrambling to find a way out.

They do so over the course of seven roll calls on the final day – marked not by a sudden rout, but rather by very gradual slippage from Fillmore to Scott. On the 52nd ballot, the General falls one shy of a majority. On the 53rd he wins as six Fillmore and five Webster men come to his side.

Voting At The 1852 Whig Convention (149 Needed To Win)

| Candidate | 1 | 8 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 |

| Millard Fillmore | 133 | 131 | 127 | 129 | 124 | 122 | 122 | 120 | 118 | 112 |

| Winfield Scott | 131 | 133 | 134 | 135 | 137 | 139 | 142 | 142 | 148 | 159 |

| Daniel Webster | 29 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 28 | 29 | 26 | 21 |

| Others | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

Before adjourning, William A. Graham is chosen unanimously as Scott’s running mate. Graham, at forty-eight, has served as Senator and Governor of North Carolina, and is currently Fillmore’s Secretary of the Navy.

What is most amazing about Scott’s victory is the inability of Fillmore to convince Webster to shift his “difference-making” votes to his side over more than fifty roll calls. At one point in his career, Webster was his mentor. Then Fillmore embraces him as his Secretary of State. The fact that this history doesn’t lead to a Fillmore nomination must attest to Webster’s pique over the President’s change of mind about running again in 1852.

August 11-12, 1852

The Vanishing Free Soil Party Nominates John Hale

While the Free Soil Party won 10% of the popular vote in 1848, it is in near total disarray four years later.

Its founding in 1844 was Salmon Chase’s attempt to form a coalition of dissident elements aimed at defeating the rival Democrats. Its banner was:

Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men

With each element carrying weight with its various factions.

- “Free soil” signals “free of all blacks” to some, along with “free land grants” for settlers to all.

- “Free speech” is a jab at the Slave Power for trying to “gag” the voice of those opposing slavery.

- “Free labor” reasserts the “dignity” of white men’s work vs. the demeaning toil of the enslaved.

- “Free men” signals Chase’s claim that the founders intended to have slavery vanish over time.

By 1848 the coalition has largely dissolved.

Those members who defected after James Knox Polk took the 1844 nomination away from their hero, Martin Van Buren have now returned to their former home as Democrats. Included here are the New York “Barnburners” and many of the Wilmot men, who still remain intent on “protecting” the new western lands for white settlers by opposing the presence of plantations and all blacks, enslaved or free.

What’s left then is a much smaller band composed of those who oppose slavery on moral grounds. Some have drifted in from the defunct Liberty Party, men like Gerrit Smith, James Birney and the Tappan brothers – and others wavering off and on between prior parties like John Hale, Joshua Giddings, Henry Wilson, Charles Francis Adams, and Owen Lovejoy.

This remnant meets eight weeks after the close of the Whig’s convention at the Masonic Hall in Pittsburgh for what will be their final active political campaign.

Over two hundred delegates are on hand as the convention opens on Wednesday, August 11. They represent a mix of older and younger figures in the abolitionist movement, among them the Reverend Charles Finney, whose “Second Great Awakening” revival meetings in the 1830’s sparked many to join the anti-slavery crusade.

One notable absentee is Salmon Chase, whose dalliances with the Democrats have distanced him by now from the party he founded.

Procedural matters dominate the first day. Henry Wilson, the Massachusetts Conscience Whig, is chosen to preside; a committee adjourns to nearby LaFayette Hall to work on an updated platform; various luminaries including Frederick Douglass offer up speeches to those left in the hall.

Douglass’ inflammatory remarks on the Fugitive Slave Act are particularly notable for their virulence:

The only way to make the Fugitive Slave law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers. A half dozen…carried down South would cool the ardor of Southern gentlemen, and keep their rapacity in check.

Action picks up on day two, with lively debates over various aspects of the platform, especially in relation to slavery. Two key planks draw much of the attention:

Number 4. That the early history of the Government clearly shows the settled policy to have been, not to extend, nationalize and encourage, but to limit, localize and discourage Slavery; and to this policy, which should never have been departed from, the Government ought forthwith to return.

Number 14. That slavery is a sin against God, and a crime against man, the enormity of which no law nor usage can sanction or mitigate, and that Christianity, humanity, and patriotism alike demand its abolition.

Several delegates lobby for a plank specifically addressing the Fugitive Slave Act:

That not only do we condemn and trample upon the enactment called the Fugitive Slave Law…but we hold all forms of piracy, and especially the most atrocious and abominable one of Slavery to be entirely incapable of legislation.

This leads to a discussion about “resistance,” including the possibility of “opposing the law with carnal weapons.”

The philanthropist Gerrit Smith disavows violence, but Joshua Giddings disagrees, referring to those who killed the slave-catcher Gorsuch (in the “Christina Affair”) as “the most efficient protectors of our Constitution.” Charles Francis Adams quickly pushes back by saying that any resort for violence would permanently alienate Southerners troubled by the ethics of slavery. Lewis Tappan proposes a platform alternative replacing Numbers 4 and 14 with a single alternative:

That as American slavery is a sin against God and a crime against man, it is in the highest sense invalid, illegal, not law, either divine or human; and is therefore utterly void, and of no force, before God and man.

The Reverend Owen Lovejoy, brother of the slain abolitionist editor, Elijah Lovejoy, finds Tappan’s option wanting, and a third option reaches the floor:

That as American slavery is a sin against God and a crime against man, which no human enactment can make right; and that Christianity, humanity, and patriotism alike demand its abolition.

This option seems to please both sides, and it is approved by a 192-15 margin.

Attention then shifts to Land Reform and approval is given to a plank demanding that ownership of the new western territories be retained by the national government for the purpose of granting small parcels to settlers, free of charge.

That the public lands of the United States belong to the people, and should not be sold to individuals nor granted to corporations, but should be held as a sacred trust for the benefit of the people, and should be granted in limited quantities, free of cost, to landless settlers.

This motion is enthusiastically approved, as part of the “Free Soil” promise of the Party.

With the platform approved, the delegates move on to the nominating process, which is anti-climactic and largely a fiasco. They select abolitionist Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire by 192-15 on the first ballot – even though Hale has already indicated that he is not interested in running. Their Vice-Presidential choice is House member George Julian of Indiana, a well known advocate for land reform and immediate emancipation.

While August 12 marks the end of the Free Soil Party as a stand-alone political entity, its core principle – opposition to the nationalization of slavery – will be picked up in 1856 by the new Republican Party to unite different Northern factions against a fracturing Democratic opposition.