Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 176: Surveys For Transcontinental Railroad Routes Completed In 1853-54

1849-1853

The California Gold Rush Tips The Scales In Favor Of A Transcontinental Railroad

Musings about a transcontinental railroad go all the way back to the 1830’s.

But the first serious promoter of such a venture is one Asa Whitney, a dry goods merchant, who makes a fortune trading tea and spices in China during a trip there in 1842-44. From this experience, he imagines the possibility of importing more goods from throughout Asia and then transporting them to eastern markets by rail. The route he envisions would begin in the Pacific Northwest at Vancouver, then swing down to the South Pass and back to St. Louis along the Oregon Trail. Whitney sums up his plan in a formal document, A Project for a Railroad to the Pacific and lobbies for it with Congress in 1849, before eventually giving up.

Whitney’s banner is picked up in 1845 by Stephen Douglas, then a freshman in the U.S. House. His proposal enjoys support, but stalls when other cities – St. Louis, Quincy, Memphis, and New Orleans – offer alternative routes.

Congress returns to the notion in 1850 when it passes the first of what will be several Land Grant Acts, this one setting aside 3.75 million acres of public property to construct a railroad from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. This land would be given free to any developer in exchange for future reduced rate shipping of government goods.

The effects of the Gold Rush, however, quickly shifts attention back to reaching California. This prompts the 1853 Appropriations Bill “To Ascertain the Most Practical and Economical Route for a Railroad From the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.”

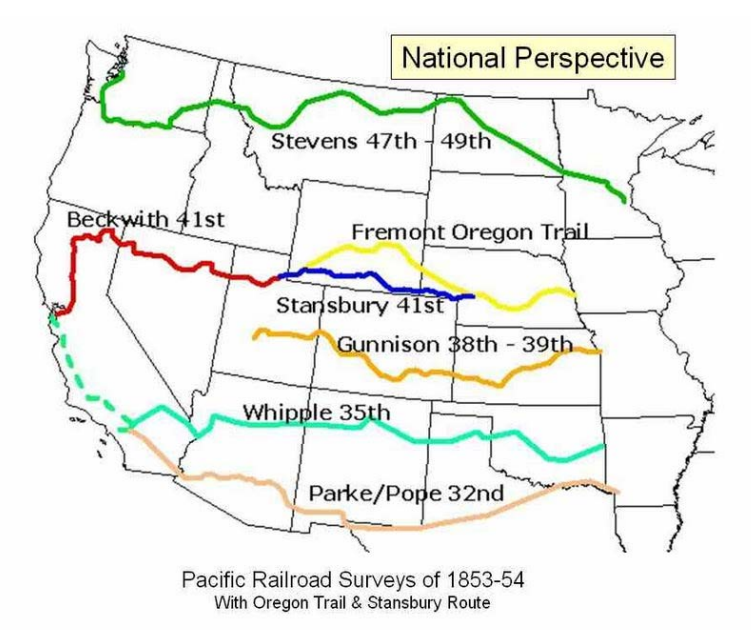

Between 1853 and 1855, four different routes to California will be explored by the Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers. These crisscross the nation at the 49th, 39th, 35th, and 32th parallels, from the Canadian border in the North to the Mexican border in the South.

At stake in the final choice is the opportunity to lead the commercial development of the west, and to reap the economic bonanza that will hopefully follow. Each of the contenders will rally its own set of potential investors and look to its own leading politicians to make their case in Congress – a task that will involve the cleverest forms of horse-trading.

Among the many maneuvers that follow will be one proposed by a frustrated Steven Douglas involving the Nebraska territory that will inadvertently spark the American Civil War.

1849-1853

Political Maneuvering Begins Over Choosing A Final Route

Political leaders have already begun to lobby for their regional interests by the time Congress officially sets aside money in 1853 for exploration.

Asa Whitney’s call for a line ending at the mouth of the Columbia River is picked up by recently named Governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, a West Point grad, veteran of the Mexican War and an early supporter of Pierce in the 1852 race. Instead of Whitney’s angle through the South Pass, he proposes a straight shot along the Canadian border at the 49th parallel. As an engineer and surveyor himself, Stevens will eventually lead the team during the actual exploratory phase.

The far Southern route along the 32nd parallel is favored by Pierce’s Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, and by the influential Charleston native, James Gadsden, who will serve as his Ambassador to Mexico. Gadsden is 65 years old and an ex-army man, having been aide de camp to Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812 and then Seminole War in Florida. He joins Calhoun’s Nullifier movement, runs his Pimlico rice plantation which boasts 235 slaves, and serves as President of the South Carolina Railroad for a decade. After proposing secession in 1850, he sponsors a bill to divide California into two states, with the southern half open to slavery and San Diego as his proposed terminal for his southern transcontinental line.

Other powerful men will argue on behalf of a central route, somewhere between the 38th and 41st parallel.

One is the aging Thomas Hart Benton, who represents Missouri in the Senate between 1821 and 1851, before being denied a sixth term for his growing reservations about the expansion of slavery. But Benton remains a giant in both Washington and Missouri, and he is dedicated to positioning St. Louis as the hub for the Pacific line.

In February 1849 the Senator unveils what becomes known as “Benton’s National Central Highway.” It proposes a line funded and owned by the U.S. government rather than by private corporations as Whitney would have it. The tracks would be laid over a strip of set-aside land – 1600 miles long and 100 miles wide – running from St. Louis to San Francisco. The route he chooses follows that taken and well documented by his “Pathfinder” son-in-law, John C. Fremont, during his 1842-45 expeditions.

Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Chairman of the powerful Committee on Territories in Congress, continues to back the central path, although, unlike Benton, he supports Chicago, not St. Louis, as the linchpin for the new line.

Benton and Douglas first clash over their differences at a National Railroad Convention which opens on October 15, 1849 in St. Louis. Benton touts St. Louis as the gateway to the west, citing its history as jumping off point for trailblazing expeditions to the coast. Douglas counters by citing Chicago’s unique access to both waterways and railroads back to the Atlantic coast.

One week later, on October 23, a second railroad convention is held, this time in Memphis. Some 400 attendees show up, including delegate Asa Whitney and a brief visit by Jefferson Davis. The outcome predictably favors a southern route heading from San Diego along the Mexican border to the Mississippi River and eventually terminating in Memphis.

June 6, 1853

Mapping The Northern Route

On June 6, 1853, the first of what will prove to be five exploratory parties heads off in search of the ideal route for the pacific railroad – one marked by straight stretches of flat land, the absence of steep grades (capable of stalling an engine), access to fresh water and lumber, and friendly tribes, among other things.

This first group is dedicated to a Northern passage along the 49th parallel. It is led by Isaac Stevens, Territorial Governor of Washington and his chief assistant, Captain George McClellan of the army engineers. They are joined by a large support contingent including topographers, artists, astronomers, geologists, botanists, meteorologists, sappers and miners, linguists, a surgeon and a quartermaster.

By August 1, Stevens has moved from St. Paul on the Mississippi River, west to the Missouri River in what will become, in 1889, the state of North Dakota.

For the next ten weeks, the expedition proceeds across Montana and into the Rocky Mountains, with several separate contingents trying to locate a satisfactory train route.

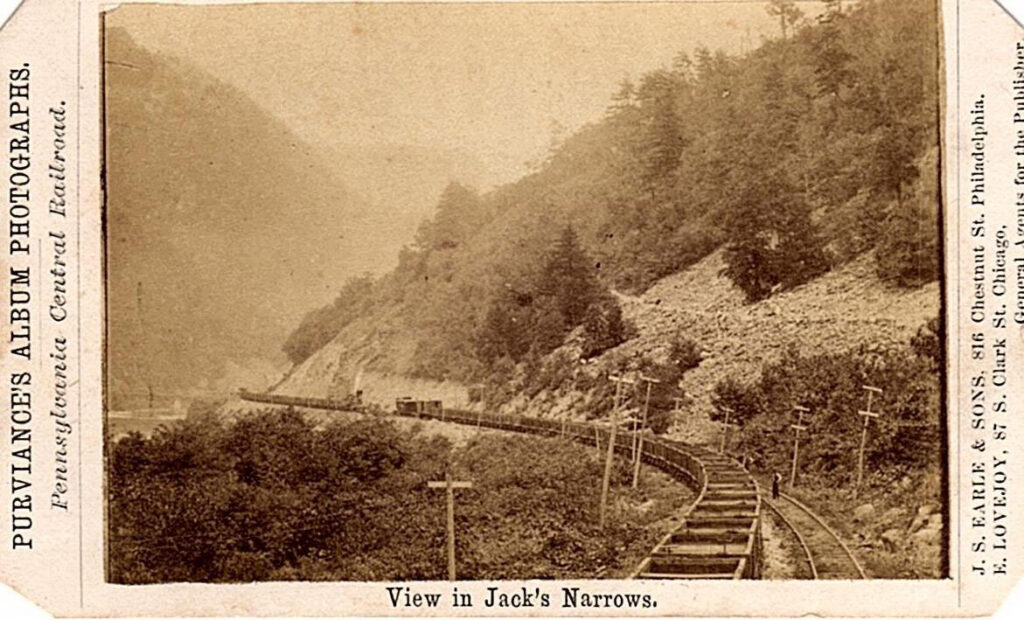

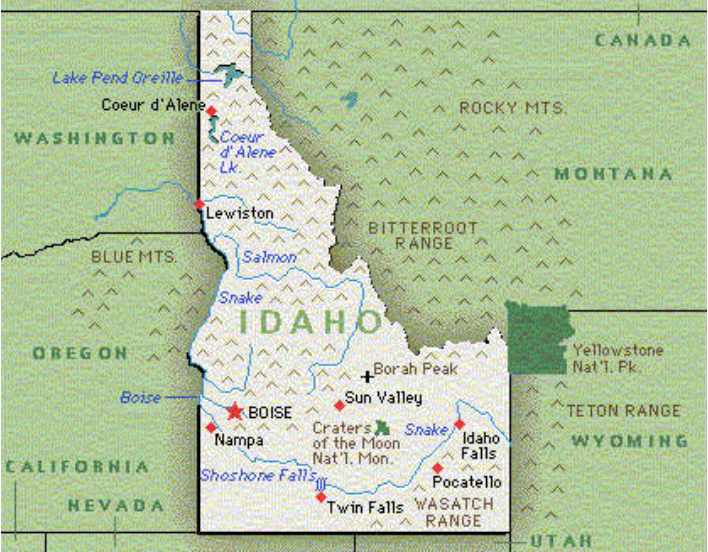

On October 18, 1853, the main party arrives at Coeur D’Alene in northern Idaho, where the Jesuits have established the Sacred Heart Mission to convert local tribes to Christianity. Among these are the Nez Pearce people who proved invaluable to Lewis & Clarke in their 1804-06 journey to the coast. Stevens’ diary records a “message from the Great Father” that he delivers at the Mission:

I am glad to see you and find that you are under such good direction. I have come four times as far as you go to hunt buffalo, and have come with directions from the Great Father to see you, to talk to you, and to do all I can for your welfare. I see cultivated fields, a church, houses, cattle, and the fruits of the earth, the work of your own hands. The Great Father will be delighted to hear this, and will certainly assist you. Go on, and every family will have a house and a patch of ground, and every one will be well clothed. I have had talks with the Blackfeet, who promise to make peace with all the Indian tribes. Listen to the good father and the good brothers who labor for your good.

After departing Coeur D’Alene, the band treks across the Washington Territory, arriving at Ft. Vancouver on November 19, 1853.

The entire trip has taken five and one-half months to complete, and the information collected will be written up in fine detail and eventually handed over to the sponsor, Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, for publication in February of 1855.

Despite Steven’s enthusiasm for “his route,” critics are troubled by the failure to identify a solid path through the Rockies, and by concerns over the likely snowfall and challenging winter conditions associated with the 49th parallel option.

June 23, 1853

Tragedy Strikes The “Central Route” Expedition

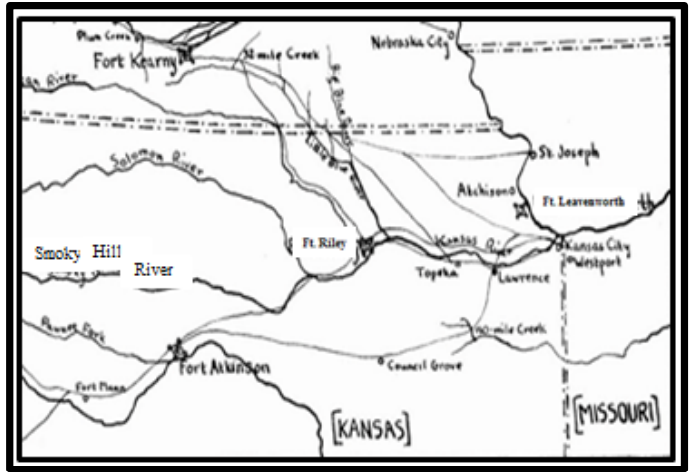

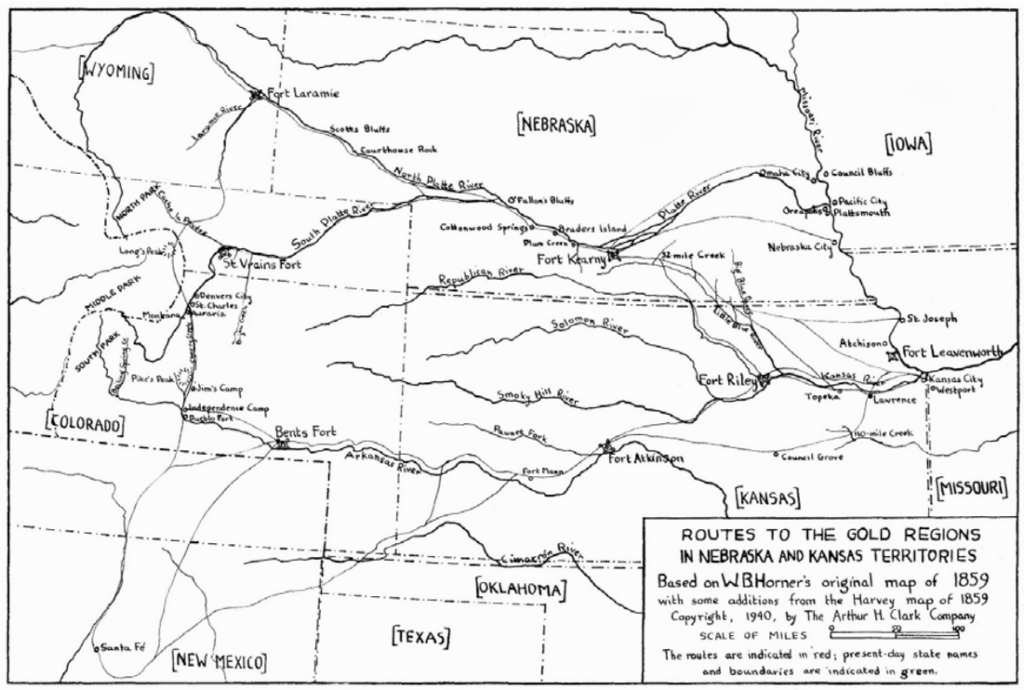

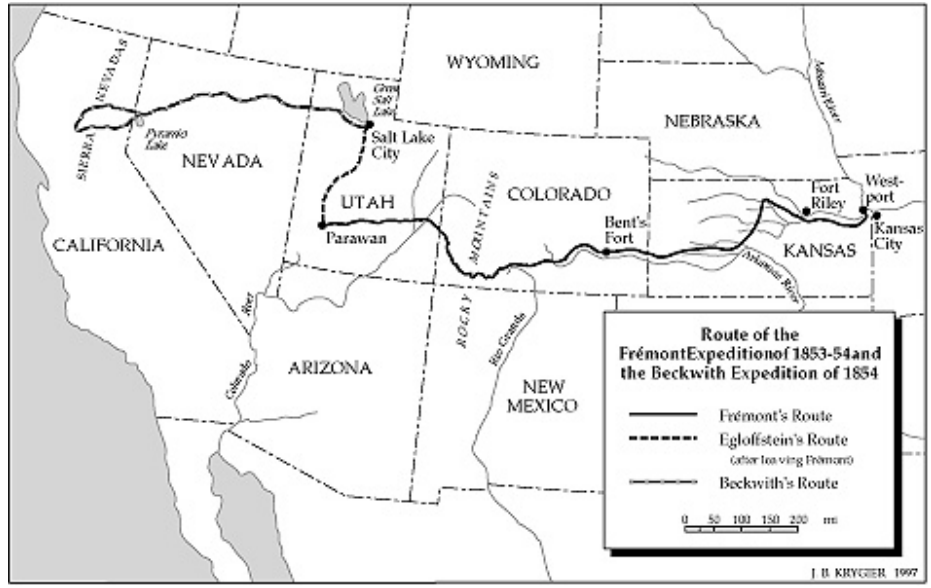

Captain John Gunnison is forty years old when he sets out along with First Lieutenant Edward Beckwith to explore a Central path, favored especially by Benton, given its jumping off point in Missouri. Their party passes through St. Louis and Ft. Leavenworth to Westport, Missouri, and departs from there on June 23, 1853, heading southwest along the old Santa Fe Trail.

On July 4 they reach Ft. Riley, where the group splits for the first time, with Gunnison heading west over unexplored ground along the Smoky Hill River, while Beckwith drops south about thirty miles along the Santa Fe Road.

Gunnison crosses the Smoky Hill River and reunites with Beckwith at Walnut Creek, a branch of the Arkansas River, east of Ft. Atkinson. At this point, Gunnison computes that he has gone 322 miles from Westport along his river route, while Beckwith has traveled 293 miles over the Santa Fe Trail.

They then continue west alongside the Arkansas River, past Ft. Atkinson and all the way to Bent’s Fort, an abandoned military outpost, where they arrive on July 29, 1853. So far the well known path they have followed offers no new surprises or barriers to a “Central” railway solution.

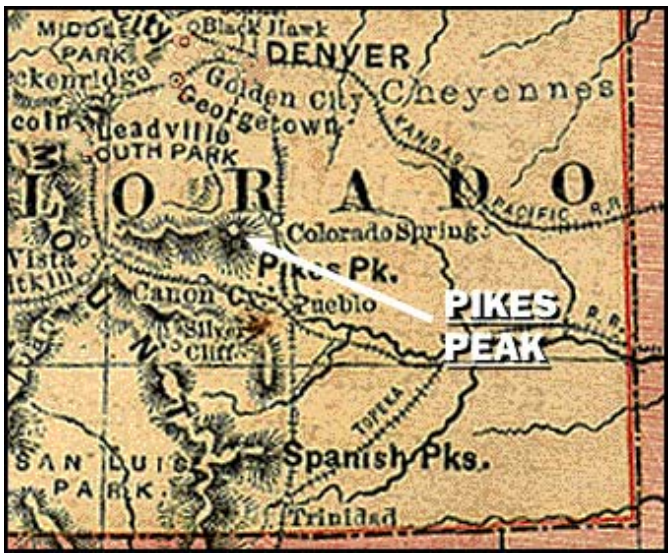

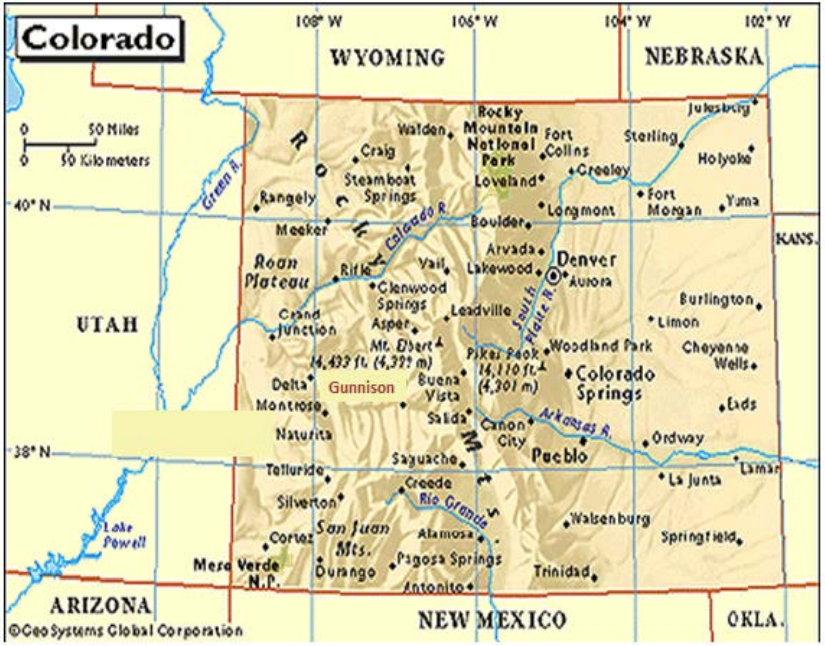

Leaving Bent’s Fort they swing sharply north and, on August 6, come upon a memorable vista centered between Zebulon Pike’s Peak and the Spanish Peaks in southern Colorado.

Pike’s Peak to the north, the Spanish Peaks to the south, the Sierra Mojada to the west, and the plains from the Arkansas—undulating with hills along the route we have come, but sweeping up in a gentle rise.

Head due west, Gunnison explores potential sites through the Spanish Peaks while Beckwith tours the San Luis Valley. Concerns are raised here about the amount of winter snow in San Luis, and the likely need for a tunnel through the mountain range coming out of the Valley.

On August 23 they reach Ft. Massachusetts and get ready to head further into the mountains toward what will later become known as the town of Gunnison, Colorado – at the eastern edge of the Gunnison River. After traveling west along the river for some forty miles, a breathtaking site, the Black Canyon, comes into view:

A stream imbedded in (a) narrow and sinuous canyon, resembling a huge snake in motion. To look down over…the canyon below, it seems easy to construct a railroad; but immense amounts of cutting, filling and masonry would be required.

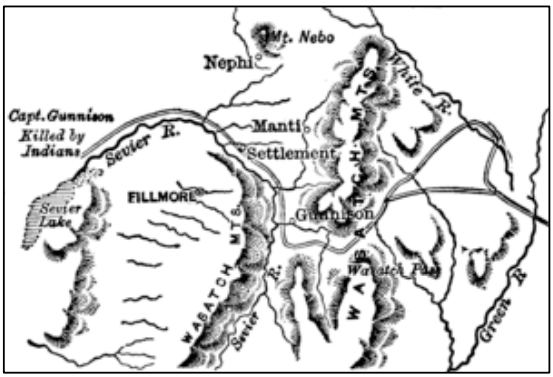

Their journey continues into Utah over the next two months, taking them down the Colorado and Green Rivers and across the Wasatch Mountains to the Sevier River, near the Utah Tribe’s Manti Settlement. Gunnison decides on October 25, to break away from the main party and explore Sevier Lake. It is a fateful decision as his detachment of twelve men is attacked on the morning of October 26, purportedly by a band of Pahvant Utes, at war with local Mormon settlers. Eight men are killed including Gunnison, who is found mutilated, with fifteen arrows in his corpse. When second-in-command Beckwith learns of the battle from the survivors, he circles back to bury Gunnison and the other victims.

The Sevier River, Sevier Lake & Where Gunnison Dies

The party has traveled some 1566 miles when Beckwith succeeds Gunnison. On October 31, he heads north to Salt Lake City, arriving there on November 8 and settling in for the winter. He receives orders to continue west, and sets out on April 4, 1854, heading across Nevada to the Sierra range, and reaching the Madeline Pass on June 25.

From the summit of the pass it would be easy, for some miles, to carry a railway on the hillsides, descending at pleasure; but further down, this would become more difficult, on account of the curves which the hill ravines would require, but it is still practicable. For this purpose the northeast side is the most favorable; for although containing the largest number of ravines, they are the smallest, and it is unbroken by cañones. The western descent of the pass is heavily timbered to near our present camp, and there is a fine warm spring, in a basin of rocks, just where we ascended the high spur to avoid the creek.

On July 12 Beckwith arrives at Ft. Redding in northern California, before ending his tour on July 15 at Sacramento.

The expedition’s final report covers both of its phases – the Gunnison-led search along the 38th and 39th parallels through Colorado, and Beckwith’s swing further north at the 41st parallel. While both routes are deemed viable in 1855, it is Beckwith’s 41st parallel leg that prevails when the actual tracks are laid between 1863 and 1869.

July 2, 1853

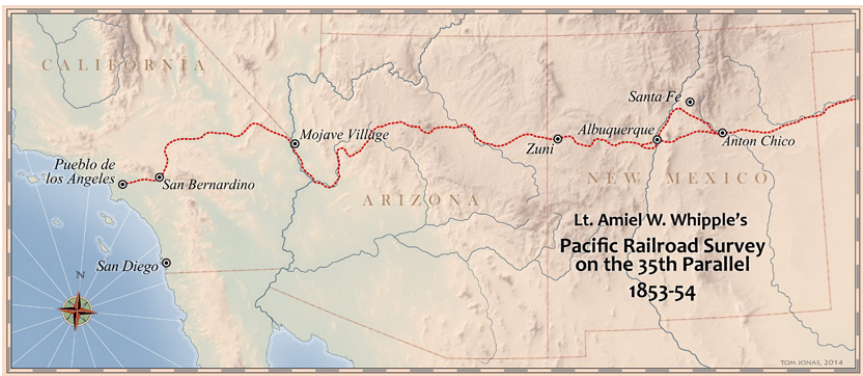

The Upper South Route At The 35th Latitude Is Completed

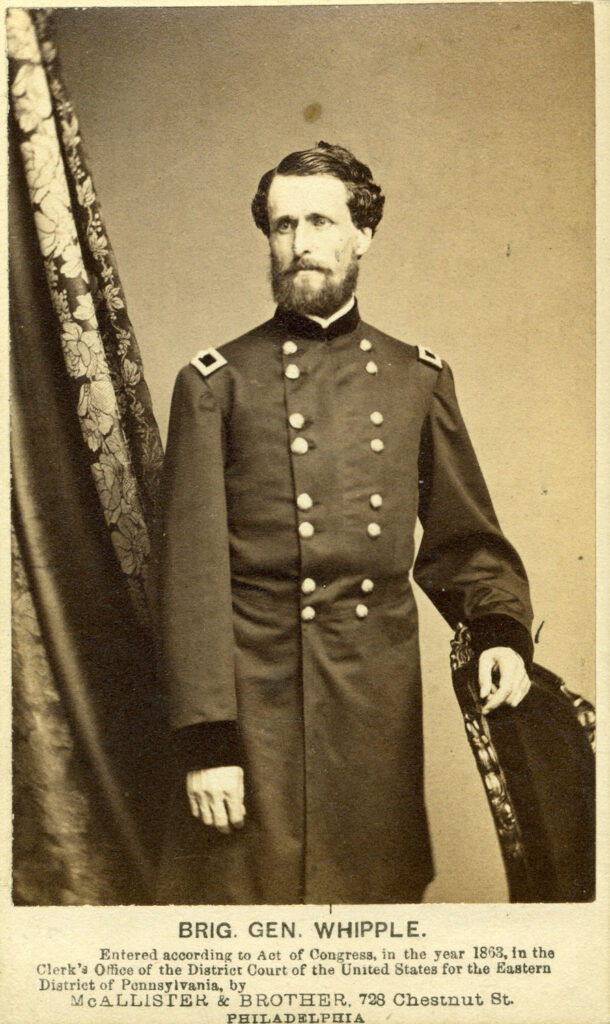

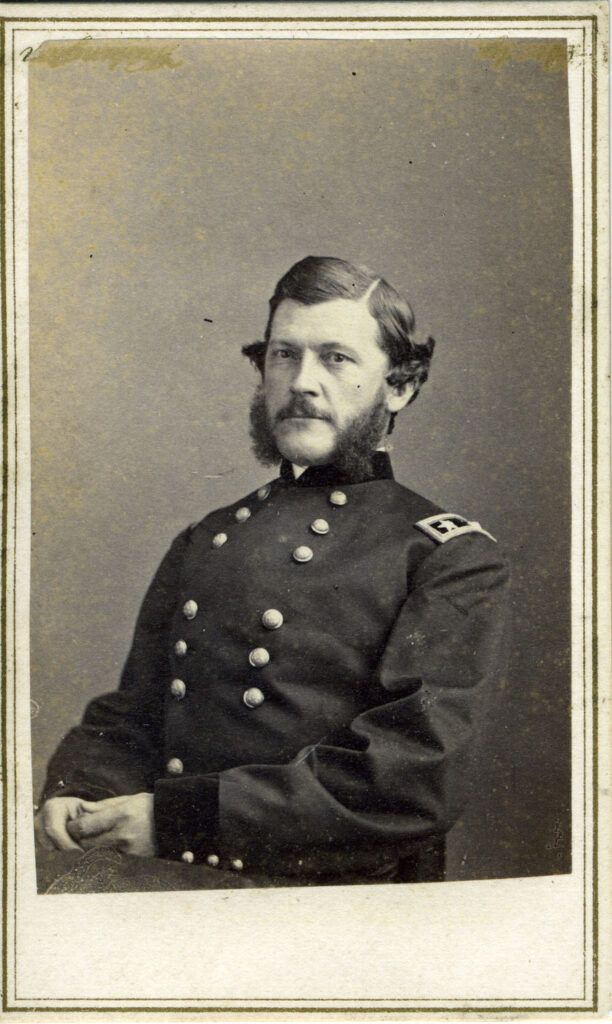

KIA Chancellorsville (1818-1863)

Lieutenant Amiel Whipple is chosen to lead the investigation of a route at the 35th parallel, from Ft. Smith, Arkansas, to Pueblo de los Angeles, California. He is 34 years old at the time, trained in astronomy, surveying and engineering, and just back from completion of work on a railroad line in Texas.

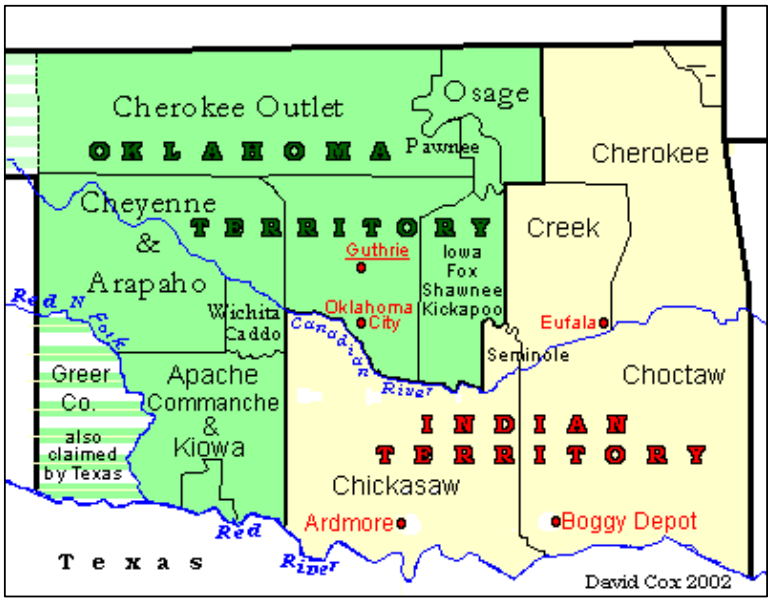

Whipple and his party depart from Ft. Smith on July 2, 1853, crossing the Arkansas border into the territory (later Oklahoma) set aside for the “five civilized tribes,” forcefully driven off their lands around Georgia in 1837. Their path takes them between the Red River to their south and the Canadian River to their north, across the homes of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Comanche and Kiowa Nations. They encounter no hostility along the way.

Proceeding west across the upper reaches of the Texas panhandle, they sweep into the New Mexico Territory at the frontier town of Anton Chico, founded in 1822 during Spanish rule. It is now “public domain land” owned by the United States, and is currently populated by some 500 settlers. Whipple arrives at Anton Chico on September 26, some two months after leaving Ft Smith.

He drives on to Albuquerque, arriving there on October 3, 1853. He splits his party there into two wings to explore the upper Rio Grande Valley for an ideal route to the west. They re-group at the Zuni trail, an old Spanish road and move on toward the home of the Zuni Nation. The Zunis are descendants of the original “Puebloans,” and are noted for their elaborately tiered adobe buildings, advanced horticultural skills, generally industrious culture, and complex religious beliefs, symbols and practices. On November 20, 1853, the expedition records impressions of an ancient Zuni site left in ruins:

The village was compactly built… The entrance to the dwellings was by a ladder, or rather post, cut into steps, and inclined to rest upon the roof…Fragments of pottery were strewn around…a piece of volcanic scoria was found, the first seen among the ruins; also an axe made of greenstone, nicely grooved and beautifully polished.

Upon returning to the Zuni village, they also encounter a distressing sight:

…a most revolting spectacle met our view. Smallpox had been making terrible ravages among the people, and we were soon surrounded by great numbers-men, women, and children-exhibiting this loathsome disease in various stages of its progress

Whipple’s band then travels some 375 miles to the north-south branch of the Colorado River, and beyond it to the edge of the Mojave Desert in southern Nevada, arriving there on January 25, 1854.

The Mojave Desert terrain runs east to west for 150 miles into southern California. It is configured in typical “range and basin” fashion – with sizable hills rising in places to 2,000 feet, graduating into rolling flatland, including Death Valley, at 285 feet below sea level. Its summer daylight heat reaches 115-120 degrees Fahrenheit, while its winter nights plunge below zero.

Standing sentinels in this “high desert” landscape are its distinctive evergreen Juniper Trees. The “up and down” features and vegetation suggest a name to Whipple’s crew:

Having watered our mulada, we travelled five miles east-northeast up a dry arroyo to its head; and thence climed a steep ridge several hundred feet high, to the lowest summit we could find…From the peculiar vegetation of this place, we propose to give it the characteristic name of Cactus Pass.

Once across the Mojave, it is up into the San Bernardino mountains and then down into the valley leading to the final destination at Los Angeles. The party arrives there on March 17, 1854, just over nine months and 1500 miles from Ft. Smith, Arkansas, where they started.

Whipple concludes that the 35th latitude route is quite viable, albeit requiring some meandering around obstacles and numerous bridges to cross frequently encountered streams. But water and wood are mostly plentiful; the tribal populations seem sufficiently peaceful; and the winters mild enough to avoid the threats of snow and ice.

January 24, 1854

Exploration Begins On The Southernmost Route At The 32nd Parallel

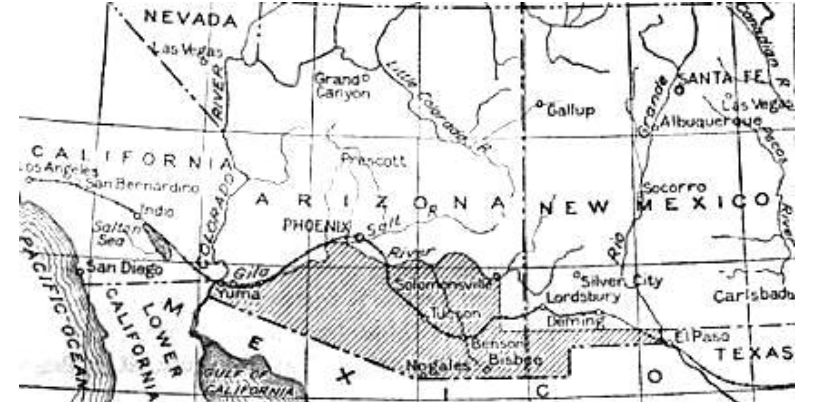

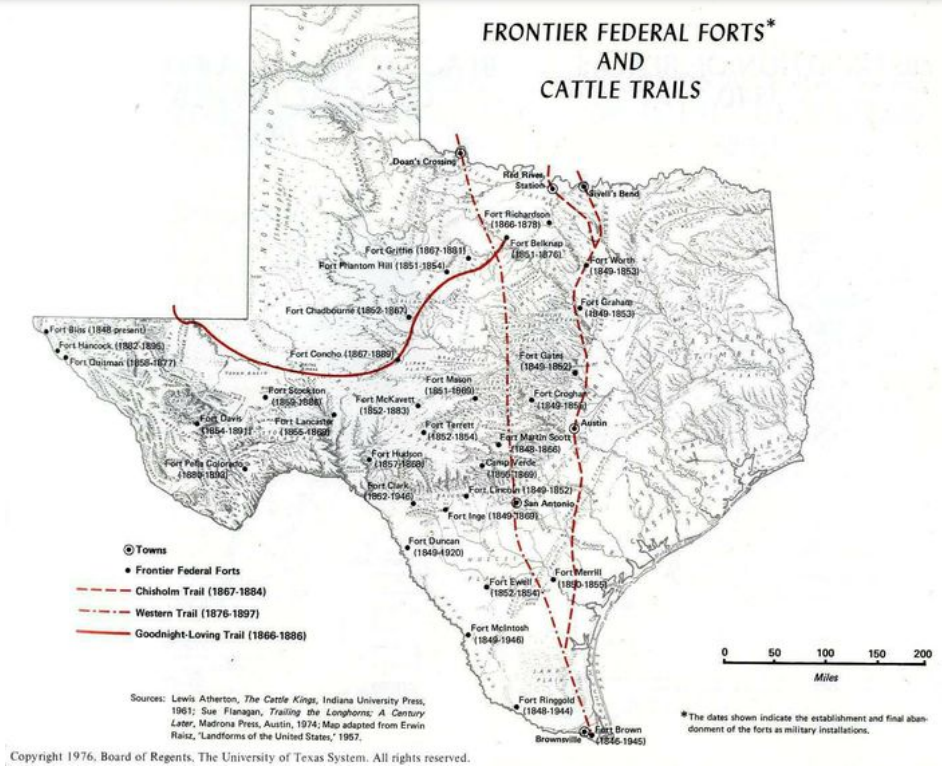

The fourth and final search for the optimum train route – this along the 32nd parallel — involves two different teams, each starting at a westernmost point and heading back east.

The first group, under twenty-six year old Lt. John Parke moves inland from San Diego along the contested border with Mexico, and ends at the Rio Grande River, near El Paso. The second, led by thirty-one year old Captain John Pope, explores a host of different routes from the Rio Grande across Texas, to his final destination at Ft. Smith, Arkansas.

Parke’s company comprises twenty-eight engineers and explorers, along with a comparable number of U.S. cavalry troops, assigned to insure their safety in case of clashes with Mexican patrols. He departs on January 24, 1854 from Ft. Yuma, on the eastern border of California, where the Gila River runs into the Colorado River. Following along the left bank of the Gila, he is soon well into the lands of the Maricopa and Pima Tribes, along a trail blazed by Captain Philip St. George Cooke during the Mexican War.

The Territory South Belonging To The Maricopa And Pima Tribes

By February 13 the band has traveled 390 miles from San Diego over easy terrain, albeit with scarce access to forage for their animals. Parke comments on this, as well as the warm reception from various tribal elders.

While on the Gila, the great scarcity of grass and other forage was a constant source of anxiety…but by dint of great care and attention on the part of Lieut. Stoneman…we succeeded in reaching the first of the Pimas and Maricopa’s villages, with all our animals, on the 13th of February…We had numerous visits from the Pimas and Maricopa’s. Their chiefs and old men were all eloquent in professions of friendship for the Americans, and were equally desirous that we should read the certificates of good offices rendered various parties while passing through their country.

Their stay is brief, and on February 16 they swing south to Tucson, arriving there only four days later, and presenting their credentials to the local Mexican commandant. Their next leg takes them further into Cochise land, past the distinctive Dos Cabezas Peaks and through the 9,000 foot Chiricahua Mountain range at the Puerto del Dado (later known as Apache Pass). They head into the Mesilla Valley and locate Ft. Webster, built to guard the Santa Rita copper mines, but recently burned, presumably by the Apaches. Parke ends his part of the Far Southern expedition on March 10, 1854, at Ft. Fillmore, on the sand hills above the Rio Grande.

The explorers have traveled a total of 550 miles between San Diego and El Paso. The path is very direct, free of any challenging mountain barriers, and ideal for laying track. The only concern cited is a scarcity of fresh water, with only nine streams available along the way.

February 12, 1854

A Second Party Completes The 32nd Parallel Assessment

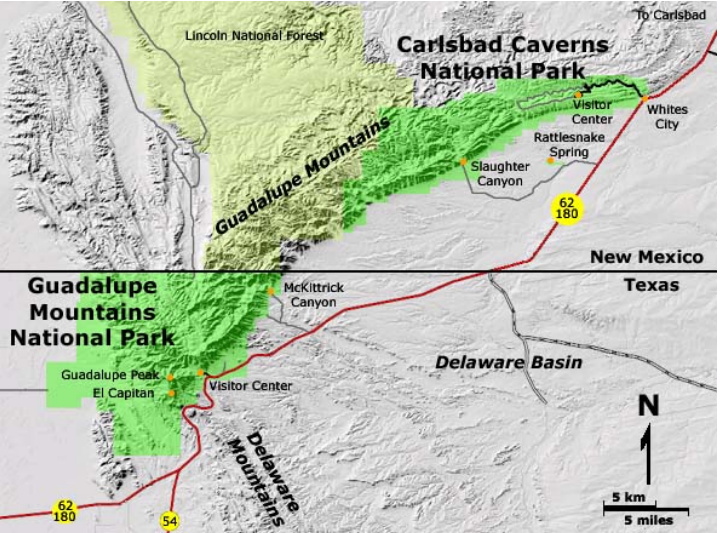

On February 12, 1854, one month before Parke arrives at El Paso, Captain John Pope sets out from Los Cruces, New Mexico, to explore potential train routes across Texas. With him are some 50 expeditionary members, and a security detail of 25 U.S. troops. Pope’s orders will take him eastward through El Paso, across the Guadalupe Mountains and onto the vast Llano Estacio Desert — then northward to the Red River border with Oklahoma, above Denton.

After navigating the Guadalupe range, Pope sets up camp for his core team in the Delaware basin. On March 10, he sends one party back into the mountains seeking a better passage, which they fail to find. At the same time he orders his second-in-command, Captain Taplin, along with ten men, to tackle what appears to be the most dangerous part of the mission, crossing a 150 mile stretch of the Llano Dessert. While waiting to hear from Taplin, Pope has some excitement of his own, when a small band of Apaches start a prairie fire hoping to drive him off their land..

On March 13, Taplin reports that he has made it across the Llano, despite having to abandon his wagons in the sandy terrain, and suffering from a lack of water. Pope breaks camp at the Delaware, traveling east across the nearby Pecos River toward the Colorado River. He also dispatches a second party to follow Taplin’s dessert path while carefully recording grades and assessing the potential to drill artisan wells for water.

After crossing the Colorado, the main body again encounters Apaches, led by one memorable chief:

They were led by a most outre looking figure. This was Sanchoz, one of their chiefs, dressed in an infantry captain’s uniform coat, silver epaulets, red sash tied over his shoulder, non-descript pantaloons, and moccasins; add to them a military cap with an enormous red pompon, and some idea may be formed of (the) exhibition….

Pope concludes that his 350 mile route would prove ideal for railroad construction. The only challenge he sees is the shortage of water experienced at the Llanos Estacio Dessert.

1856

Secretary Of War Davis Issues His Final Report On The Four Expeditions

In addition to the $150,000 set aside in 1853, Congress approves another $190,000 to complete the expeditions.

Reports from the teams flow into Washington throughout 1854, each providing careful details about the western landscape – not only related to railroad engineering but also regarding fresh water, lumber and forage, local geology, vegetation, botany (fauna, flowers, trees, etc.), zoology (mammals, birds, fossils,) climate, barometric pressures, temperatures, astronomical locations, indigenous people, language and customs.

The facts are accompanied by artist’s renderings, diaries and official records to bring the science to life.

Between 1855 and 1860 a total of twelve leather bound volumes will be printed and published on the surveys, at a further expense of $1.3 million for some 20,000 copies. Together they chronicle the sum total of existing knowledge about the Territories. The content is widely covered in newspaper reports and referenced in ongoing debates about the railroad.

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis is charged with recommending the optimal route to Congress, and he is both serious and objective in this duty – and he announces his conclusion before Congress in 1856.

As will be demonstrated over time, he finds all options viable, albeit with different degrees of difficulty and investment.

Still, the hands-down winner is the southernmost path from New Orleans through Texas to El Paso, and on to Yuma and Los Angeles. The route is very direct, over land that has relatively few mountains, and a generally mild winter climate. Its only drawbacks are some areas where water and forage are scarce, and a strip of land west of El Paso that remains disputed with Mexico (soon to be resolved with the “Gadsden Purchase”).

1869

Future Construction Of The Railroads

Unfortunately the ambitious plan to begin construction on the railroad is postponed due to sectional animosity that intensifies in the 1850’s over the future of slavery in the west.

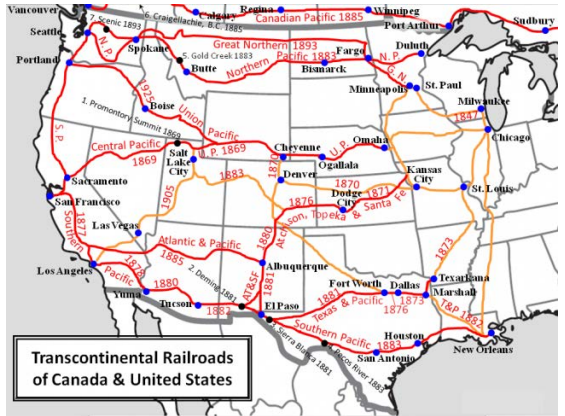

Action materializes only after the South secedes from the Union and the Civil War is underway. On July 1, 1862, then President Lincoln signs the Pacific Railway Act incenting two corporations to construct tracks along a central route at the 40th parallel, from Council Bluffs, Iowa to San Francisco, California.

Ironically this is the path terminating in Chicago favored by Senator Stephen Douglas since 1845 and ignored during the 1853-55 surveys. The Little Giant, however, never lives to enjoy his success — dying suddenly on July 3, 1861, of typhoid fever, at only forty-eight years old.

The Two Corporations Who Build The First Transcontinental Line By 1869

| Corporations | Line Runs | Key Owners | Details |

| The Union Pacific | Council Bluffs, Iowa Omaha, Nebraska Cheyenne, Wyoming Ogden, Utah Promontory Point, Utah | Dr. Thomas Durant In 1880, Jay Gould | Construction head is J.D. “Pete” Criley, backed by largely Irish vets of the Civil War working for a handsome $2 a day. |

| The Central Pacific (later the Southern Pacific line) | Promontory Point, Utah Sacramento, California San Francisco, California | “The Big Four” Leland Stanford Collis Huntingdon Charles Crocker Mark Hopkins | Begun in 1863 with Crocker as construction head and 15,000 laborers, 80% Chinese immigrants |

This deal struck by the ex-Whig Lincoln is right out of the Henry Clay playbook for developing needed infrastructure through a combined public and private partnership – with each side sharing in the risks and the rewards.

The underlying assumption is that “demand” for the new railroad will be sufficiently great to offset what are certain to be staggering construction costs. For this to be the case, the new trains must transport both goods and passengers at a much faster rate and with less risk than the existing option – ships sailing around South America’s Cape Horn.

The 1862 bill gives each corporation “rights of way” land grants to lay their tracks, surrounded by 200 feet on each side of the rails. In total, some 175 million acres — equaling the size of Texas – are handed over by 1871.

The capital required for construction is raised through government backed bonds issued to investors with a guaranteed 6% per year rate of interest. The target amount assumes roughly $16,000 per mile of track laid on flatter land, and from $32,000 to $48,000 per mile between the Rocky and Sierra Mountain ranges. This money is temporarily loaned to the corporations to cover their costs for building the lines – to be repaid in full once the trains are running and producing revenue for the private owners.

After some six years of hard labor by largely Chinese and Irish work crews, the two lines – spanning 1,928 miles — are joined at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869. By November of that year, commercial traffic is up and running, including passenger travel from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Francisco, for a one-way fare of $65.

The costs to construct the first line are less than originally thought, albeit still immense — at $36- 52 million for the Central Pacific portion in the west, and another $60 million for the much longer, but “easier” Union Pacific branch.

Once shaken down and running smoothly, the hoped-for advantages of the transcontinental train for both commercial shippers and passengers are readily apparent – in greater speed and reliability.

Time From New York To San Francisco — 1876

| Number Of Days | |

| Transatlantic Railroad | 4-10 Days |

| Sailing Ships | 100 |

| Wagon Train | 150 |

What follows is a financial boom for the railroad corporations that mirrors the gold rush, and tycoon status for the lead investors, who are soon known as “Robber Barons” for their ruthless business practices.

The Early “Robber Barons” Of Railroading

| Mark Hopkins (1813-1878) | Leland Stanford (1824-1893) |

| Henry Plant (1819-1899) | Henry Flagler (1830-1913) |

| Collis Huntington (1821-1900) | Jay Gould (1836-1892) |

| Charles Crocker (1822-1888) | E. H. Harriman (1848-1909) |

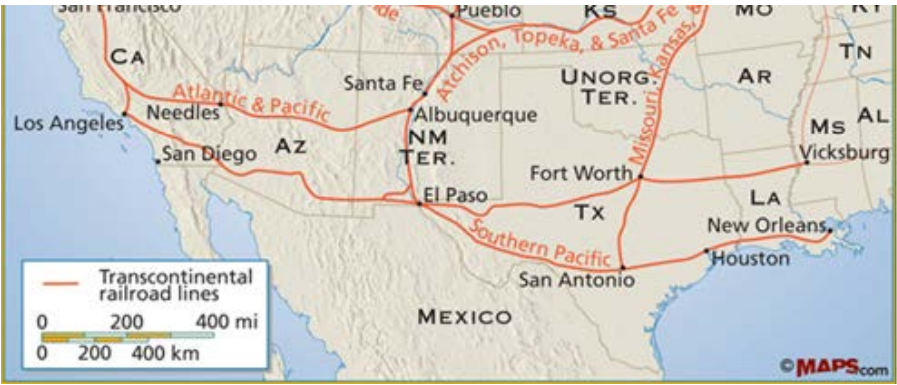

The rapid financial success of the Central line spurs other corporate entrepreneurs to follow suit.

On January 12, 1883 the Southern Pacific completes its construction along the 32nd Parallel route explored by Parke and Pope in 1854. It connects New Orleans with Los Angeles. Eight months later, on September 8, 1883, the Northern Pacific celebrates its Completion Ceremony in western Montana, with then President Ulysses Grant in attendance. It traces the 49th Parallel line favored by Isaac Stevens in 1853, and links St. Paul, Minnesota to Portland, Oregon.

Two More Transcontinental Lines Are Completed In 1883

| Corporations | Line Runs | Key Owners |

| Southern Pacific | New Orleans, Louisiana San Antonio, Texas Sierra Blanco, New Mexico El Paso, Texas Tucson, Arizona Yuma, Arizona Los Angeles, California | Timothy Phelps 1865 Sold in 1868 to the “Big Four” |

| Northern Pacific | Chicago, Illinois Minneapolis, Minnesota Fargo, North Dakota Bismarck, North Dakota Bozeman, Montana Butte, Montana Portland, Oregon | Chartered in 1864 Early tycoons are J. Gregory Smith followed by Jay Cooke |

Finally there are the “connector lines” that are crucial to making the entire system efficient. Some, like the Atchison, Topeka & The Santa Fe provide north-south arteries that complement the east-west drift of the transatlantics. Others, like the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific, act as the central hub linking the west and east coasts.

Major “Connecting Lines” To Transatlantic Railroads

| Corporations | Line Runs | Key Owners |

| Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Links Missouri to Southern Pacific RR | Hannibal, Missouri St Joseph, Missouri Atchison, Missouri Topeka, Kansas Pueblo, Colorado Santa Fe, New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico El Paso | Cyrus Holliday, first president 1860-63 |

| Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific | Chicago, Illinois Rock Island, Illinois Iowa City, Iowa Omaha, Nebraska | Incorporated in 1847 by civic leaders in Rock Island |

| Missouri Pacific | St. Louis, Missouri Kansas City, Missouri Topeka, Kansas | Starts in 1851 then Jay Gould takes over 1871 |

| Kansas Pacific | Topeka, Kansas Denver, Colorado | Began in 1855; later a part of the UP line. |

Denver Pacific | Denver, Colorado Cheyenne, Wyoming | 1867 start; later ties to KP and UP routes |

Atlantic & Pacific | Albuquerque, New Mexico “Needles,” Arizona Tehachapi Pass, California San Francisco, California | Opens in 1849 tying St. Louis to Kansas City. Fremont and Charles Fisk involved over time |

The development of these great railroad line has a transformative effect on the U.S. economy, with GDP growth jumping up almost 7% per year between 1869 and 1879.