Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 174: Douglas’ Plan To Organize The Nebraska Territory Fails Again In The Senate

February 10, 1853

The U.S. House Passes Douglas’s Nebraska Territorial Bill

As the 32nd Congress reconvenes for its final session in December 1852, Stephen A. Douglas prepares to again push his plans to transform the Mississippi Valley and the west, creating new wealth in the region to rival the Northeast corridor.

At forty years old, the Illinois Senator has already established himself as the combative leader of the Democratic Party in Congress, even though his run at the nomination in 1852 offends some within the party – namely, the “Old Fogies” contingent, led by James Buchanan, twenty-two years his senior and determined to be next in line after Pierce.

Through his combination of brains and willpower Douglas is the driving force behind the “Young America” movement which intends to discard the Party’s strict commitments to an agrarian economy, and its opposition to federally funded infrastructure initiatives, such as a transcontinental railroad.

To do so, however, he must first gain agreement in Congress on governance for the “Unorganized Territory” – the land to the west of Iowa and Missouri, through which the line would eventually run.

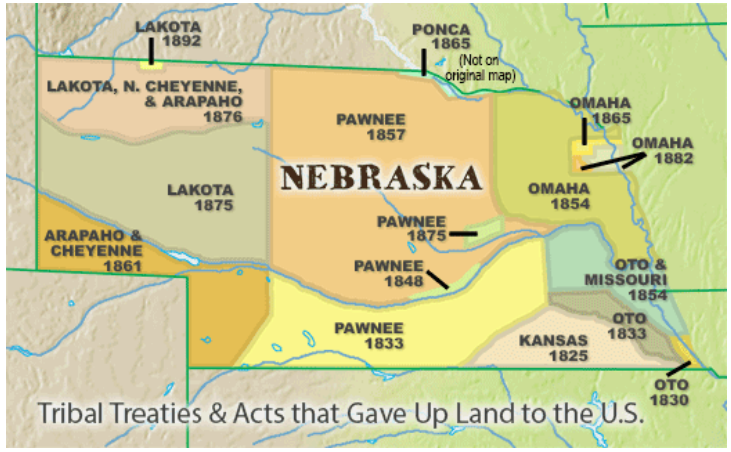

In 1852 this land is dominated by a range of Plains Tribes, mainly the Lakota’s in the far west, the Pawnee in the center, and the Omaha, Oto, and Kansas to the east. The name assigned to the area in Washington is the Nebraska Territory from the Oto Tribe word for the Platte River meaning “flat water.”

Time is short for Douglas, since the final session of the 32nd Congress runs only from December 6, 1852 to March 4, 1853. Given this, his focus is on passing two bills high on his agenda – the organization of the Nebraska Territory and funding to explore routes for the transcontinental railroad.

On January 19, 1853, however, a family tragedy slows his momentum. His 28 year old wife dies after giving birth to his third child, a daughter, who is also lost within a month.

While strickened by the loss, the senator still proceeds with his congressional duties. He works on the Nebraska Bill in the House with Illinois Congressman William A. Richardson, who later becomes Governor of the Territory.

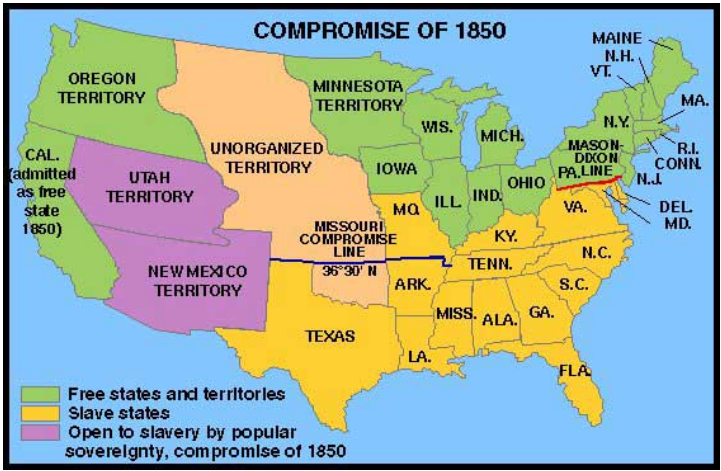

When the bill reaches the House floor, it stirs relatively little controversy. Some concerns are raised about the fate of the Indian tribes on the land, but the more controversial issue of slavery is only referenced in passing. The reason being that since the bulk of the territory falls above the 36’30” Missouri Compromise line, it will become a “Free State” by default.

Despite some conjecture about splitting the territory into two states — the second to be called Kansas — the House bill simply treats Nebraska as one entity. On February 10, 1853 a vote is taken and the bill passes by a 107-49 margin, with the nays coming from Southerners who protest the assumed restriction on slavery.

All that now remains for Douglas is passage in the Senate.

March 4, 1853

The Nebraska Bill Is Tabled In The Senate By The South

Various versions of the Nebraska Bill have been before the Senate for at least eight years, and all have foundered to some extent over its likely impact on the route chosen for the transcontinental railroad.

Douglas now runs into this same resistance once again.

The measure comes up amidst a flood of other proposals right before the session ends. On March 2, approval is given to creating the Washington Territory out of what was northern Oregon. On March 3, 1853, one day before Pierce’s inauguration, Douglas’s second priority, the appropriations bill for $150,000 to explore five rail routes to the Pacific, is approved.

With time running out, Douglas finally succeeds in again bringing his Nebraska Bill to the floor on March 4. His anger over the delay is apparent in his opening remarks:

For two years past the Senate has refused to hear a territorial bill. For the past two weeks I have sat here hour after hour endeavoring at every suitable opportunity to obtain the floor.

But neither these chastisements, nor his impassioned rhetoric on behalf of the measure, are sufficient to achieve the victory he wants. In fact, his remarks are delivered to a near empty chamber, eager to adjourn. They end with another disheartening defeat, as the senate refuses to “take up debate” on the bill by a margin of 23-17.

Senate Vote To Debate Douglas’s Bill

| Section | Ayes | Nays |

| Southerners | 2 | 15 |

| Northerners | 15 | 8 |

| Total | 17 | 23 |

Of the 17 votes cast by Southerners, the only two “ayes” belong to the senators from Missouri who, like Douglas, favor a central route for the pacific railroad.

The implications from this are clear to the senator. If the Nebraska Territory is to be settled, Douglas must find a way to sweeten the pot for the South.

For the moment, however, he is frustrated by his last second defeat and still distraught over the loss of his wife. In response, he sets sail on May 14, 1853, for what will be a five month excursion through Europe and over to Russia. He is greeted warmly from London to France, Rome (where he converts to Catholicism), Constantinople and St. Petersburg.

Douglas will return to America on October 20, 1853, refreshed and ready to resume his agenda on Nebraska.