Section #6 - The Second Religious Awakening sparks early moral concerns about slavery

Chapter 54: The Awakening Prompts New Religious Movements

1820’s Forward

The Church Of Latter Day Saints (Mormons) Is Founded

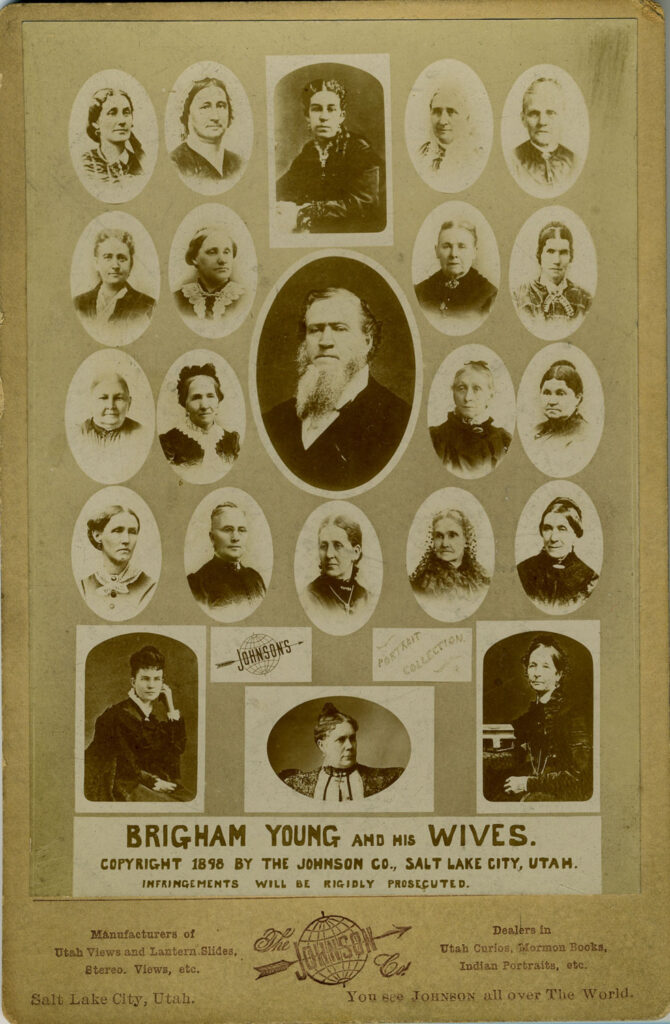

21 of his Wives

Mormonism is founded by Joseph Smith, Jr., who grows up in family of Christian mystics in western New York, the epicenter of revivalism.

As a young man, Smith is caught up in the religious fervor surrounding him, experiences a vision of his personal salvation, and begins to share his story with others in his community. He tells of being visited by an angel named Moroni in 1823, who revealed the location of a sacred book comprised of gold plates, compiled by the prophet, Mormon. He then describes his use of a “seer stone” to translate the engravings on the plates. The result is The Book of Mormon, a history of a long vanished Christian community living in America from roughly 500BC to 500AD. Some 5,000 copies of book are printed and distributed around Smith’s home town of Palmyra, New York, in 1830.

The outcome of Smith’s book and his testimonies to others is a quest to locate the land where these aboriginal Christians lived and, once there, to build a new American Jerusalem . The quest for this New Jerusalem takes Smith and his followers on a 16 year journey west, which eventually ends the Utah Territory. Along the way there are many often tragic stops, involving local opposition from those who view the Mormons as heretics..

In 1831, the first stop is in Kirkland, Ohio, where the new “Church of Christ” opens. But Smith’s sights for the new Zion are further west, in Jackson County, Missouri, and his missionaries flock there to lay the groundwork. This leads to the First Mormon War of 1838, with the original Missouri settlers, backed by the state’s Governor, driving the unwelcome band east into Illinois, where they settle in the town of Nauvoo.

At Nauvoo, Smith codifies the underlying beliefs and organizational structure of his church, as well as writing a description of his original heavenly visitation. The doctrines of exultation (“unity with Christ” achieved by living a virtuous life) and “plural marriage” (polygamy) are formulated here.

On June 27, 1844, the long-term viability of the Nauvoo settlement ends when both Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum are killed by a hostile mob in nearby Carthage, Illinois.

After a crisis over “church succession,” Smith’s close ally, Brigham Young, emerges as the new leader of the bulk of the congregation. Young recognizes the need to resume the search for a new, sustainable site, and by 1847 he settles on land beyond current civilization, the “Mormon Corridor,” in what will become the state of Utah. There, in the dessert region, he begins to build his New Jerusalem.

And it burgeons, driven from a co-operative economic approach, aggressive missionary work (home and abroad), and plural marriage, which supports rapid population growth. At long last the Mormons have found their lasting home.

They face only one more threat, and it turns out to be relatively minor. In 1857, President Buchanan sends a military force to Utah to assert federal authority over the land. This will become known as the Second Mormon War, but it is essentially a bloodless affair, and ends in 1858 when Brigham Young transfers his title as governor over to a non-Mormon resident.

1820’s Forward

The Millerites Appear And Morph Into The Seventh Day Churches

Another purely American sect – the Millerites — also springs up in New York during the awakening period.

Its founder is William Miller, who is born in 1782 in Massachusetts and grows up in Hampton, New York.

Miller becomes a well-respected member of his rural community, a successful farmer, Justice of the Peace, and member of his local militia.

Like others of his era, his limited formal education is no impediment to his determination to study the Bible and interpret it on his own. This process leads him from his religious origins as a Baptist to the Deist view of a God who created the world but is removed from its daily outcomes .

His convictions change, however, based on his combat experiences during the War of 1812, as a Captain in the U.S. Regulars. After a bloody Battle at Plattsburg, Miller decides that God’s hand must have saved his unit.

It seemed to me that the Supreme Being must have watched over the interests of this country in an especial manner, and delivered us from the hands of our enemies… So surprising a result, against such odds, did seem to me like the work of a mightier power than man.

After the war he returns to his farm and his Bible studies, focusing now on the inevitability of death and prospects for an afterlife. He gradually returns to the Baptist Church in town, becomes a reader, and is “born again” into faith in a savior both compassionate and engaged in the affairs of men.

When his Deist friends challenge his conversion, Miller intensifies his reading of Bible verses, and comes to focus on Daniel 8:14, which he regards as a prophecy about the timing of “the second coming of Christ.”

Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed.

Through further agonizingly detailed scriptural analysis he tries to pinpoint the event on the calendar. In 1822 he declares that the “2300 days” will be up on or before the year 1843:

I believe that the second coming of Jesus Christ is near, even within twenty-one years, on or before 1843.

In 1832, amidst the awakening fervor, a Baptist newspaper, The Vermont Telegraph, publishes a series of articles proclaiming Miller’s prediction. This transforms one man’s inquiry into a movement, first regional, then national, with thousands of believers, known as “Millerites,” ordering their lives for the second coming.

Miller finally zeroes in on a time between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844, as the day of reckoning. When both dates come and go, a wave of disappointment strikes the movement’s followers. A stricken and contrite Miller issues a public apology, while continuing to believe, up to his death in 1849, that his miscalculation was a minor one.

Most Millerites now disband – but not all.

One contingent that lives on is drawn more to Miller’s intricate textural analyses than the precision of his dates for the reappearance of Christ. It reexamines the ancient scriptures and concludes that the Daniel verse actually foretells an “ascension” into the Most Holy Place in heaven rather than a return to earth.

It also sets out to reestablish the practice of observing the Sabbath, not on Sunday – which they regard as a corruption of the Catholic Church — but from sundown Friday through sundown Saturday. This leads to a host “Seventh Day” Churches, with the Seventh Day Adventists eventually achieving the largest following.

1820’s Forward

Utopian Movements Dot The Landscape

While some movements seek to reform society, others decide to opt out of it.

Their motivations tend to be religious in character, driven from a shared belief that American values have gone astray – with communal well-being and personal salvation sacrificed to materialism and the chase after upward mobility.

For the Amish, Mennonites, Shakers and others, the way out of this moral trap lies in escape, in accord with the Biblical admonition:

Keep thyself unspotted from the world.

They accomplish this by setting up communities of fellow believers in rural settings, removed from the temptations and distractions they associate with modern society.

Their daily lives are marked by a return to nature, asceticism, and contemplation.

They farm the land, dress simply, reject personal adornments and class distinctions. Some sects attempt to redefine gender roles, others even challenge conventional marital and sexual practices.

Their theology is typically Christian, albeit tilted toward Old Testament dictates.

Outsiders characterize these sects as Utopian, after the name given an imaginary island nation in a book written in 1516 by St. Thomas More, the English lawyer, Lord Chancellor and Catholic saint, executed for opposing Henry VIII’s claim to head the Church of England. Moore’s vision is of an ideal community where:

Nobody owns anything but everyone is rich – for what greater wealth can there be than cheerfulness, peace of mind, and freedom from anxiety?

Thus the Utopian sects and experiments attempt to flee from the materialistic values they see shaping American society and escape toward a classless alternative based on virtue not wealth. Moore sees simple justice in this transformation to Utopia:

For what justice is there in this: that a nobleman, a goldsmith, a banker, or any other man, that either does nothing at all, or, at best, is employed in things that are of no use to the public, should live in great luxury and splendour upon what is so ill acquired, and a mean man, a carter, a smith, or a ploughman, that works harder even than the beasts themselves, and is employed in labours so necessary, that no commonwealth could hold out a year without them, can only earn so poor a livelihood and must lead so miserable a life, that the condition of the beasts is much better than theirs?

The themes played out in these isolated communities – be they Amish, Mennonite, Shaker or others that follow on – become an integral part of America’s Second Great Religious Awakening.

1820’s Forward

The Lasting Impact Of The Second Awakening

The Evangelical fervor that crisscrosses the landscape in the 1820’s will prove to be a turning point in antebellum American history.

The constant threat of foreign invasion has waned, and “we the people” step back and reflect on how far the new nation has come in its first 50 years of existence – and what it needs to do next to live up to its original vision.

In characteristic American fashion, the “revival meetings” place the burden for corrective action on each man or woman who steps forward to be saved.

If society needs changing, it is up to individuals to act. And act they will.

A few will seek a better life by retreating to isolated communes; most will pursue remedies for everyday ills they encounter close to home, in their towns and on their streets.

Their “causes” will vary.

A Temperance movement gains widespread public support. Calls arise to reform child labor laws. Food kitchens and welfare sights appear to help the impoverished. Efforts are under way to improve prison conditions and to spare Debtors from harsh sentencing. Women begin to band together to have their voices heard in what remains largely the affairs of men.

But one cause will alter the nation’s destiny – it is the effort to wash away the stain of slavery that has blemished America’s soul since 1607.