Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 26: Violence Remains A Norm For Resolving Public Conflicts

1621 And Forward

America Adopts European Style Dueling

While America seeks to become a nation of laws, it continues throughout the nineteenth century to embrace violence as a means of resolving disputes.

Thus a perceived wrong leads to “calling a man out” and engaging in some direct form of battle, from simple fisticuffs to use of deadly weapons.

In less sophisticated circles this is referred to as “frontier justice” – while among the more refined it is elevated to the art of dueling.

Dueling is inherited from traditions of the European aristocracy and practiced throughout the colonial period.

The first recorded duel in America takes place in 1621 in the Massachusetts Colony between an Edward Doty and an Edward Lester. It is fought with longswords and ends with minor wounds to both parties. But dueling will also lurk in the biographies of many of the nation’s most famous political figures, and will threaten to invade the halls of Congress in several notorious instances.

Taken to the extreme, dueling glorifies the notion of “better to die with honor than live in shame.”

1621 And Forward

America Adopts European Style Dueling

While America seeks to become a nation of laws, it continues throughout the nineteenth century to embrace violence as a means of resolving disputes.

Thus a perceived wrong leads to “calling a man out” and engaging in some direct form of battle, from simple fisticuffs to use of deadly weapons.

In less sophisticated circles this is referred to as “frontier justice” – while among the more refined it is elevated to the art of dueling.

Dueling is inherited from traditions of the European aristocracy and practiced throughout the colonial period.

The first recorded duel in America takes place in 1621 in the Massachusetts Colony between an Edward Doty and an Edward Lester. It is fought with longswords and ends with minor wounds to both parties. But dueling will also lurk in the biographies of many of the nation’s most famous political figures, and will threaten to invade the halls of Congress in several notorious instances.

The rituals surrounding the combat are carefully codified in a manual published in Ireland in 1777 called the Code Duello. This details some 25 rules required to execute a fair duel, including:

- The proper issuance of “a challenge” from the offended party;

- Selection of “seconds” to accompany the combatants and see to their needs;

- The choice of weapons, left open to the recipient of the challenge;

- Declaration of a time and place for the event;

- Exact rules of engagement (e.g. shots fired, blows struck, other “allowances”);

- How final “satisfaction” will be expressed and delivered;

- Proper care for those who are wounded or killed;

- Notification of kin in case of death; and • Procedures for calling the duel off short of actual conflict.

The vast majority of “challenges” are in fact resolved “off the field” – using one’s “seconds” to talk through the underlying grievances and arrive at “gentlemanly resolutions.”

Intemperate men, such as future President Andrew Jackson, will never “walk away” from a challenge, and will both give and receive grievous wounds in the course of several duels. The more controlled future President, Abraham Lincoln, will find a peaceful way out when he is challenged.

Only 20% of duels end with shots fired, and the majority of these yield treatable wounds to the legs. “Deloping,” or firing one’s shot into the ground, is considered a gentlemanly way to conclude a confrontation.

But at times, duels can have lethal outcomes.

Such is the case 1804, the third year of Jefferson’s presidency.

July 11, 1804

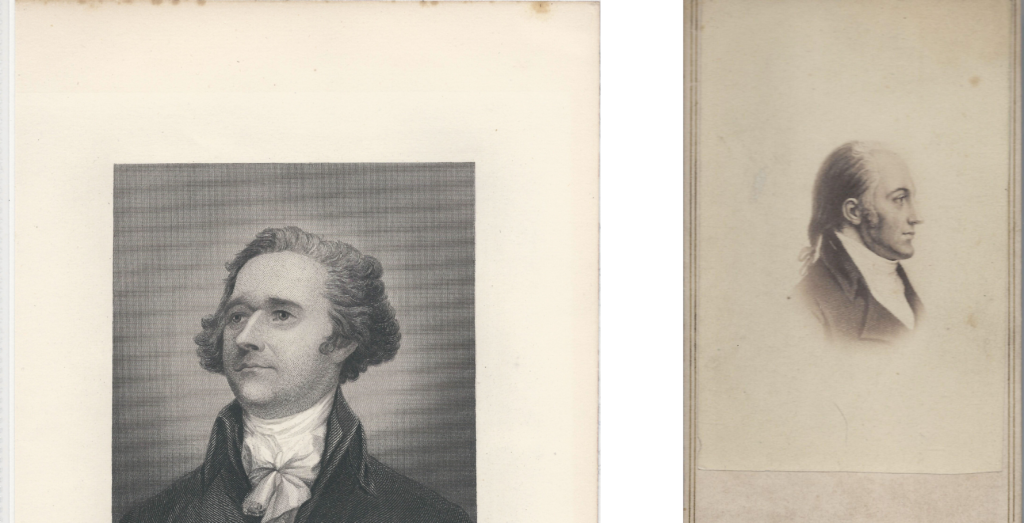

Aaron Burr Kills Alexander Hamilton

On July 11, 1804, Americans learn that Alexander Hamilton, the head of the Federalist Party and former Treasury Secretary, has been shot dead in a duel with their current Vice-President, Aaron Burr.

The bad blood between the two is long-standing.

Both men serve nobly under Washington in the Revolutionary War, but the General always seems to favor Hamilton, a source of some early animosity. Burr fails to get the field promotion he feels he deserves for saving the army on Manhattan. He also fails to get Washington’s support for a ministerial post to France; and it becomes clear that the General regards him as overly ambitious and prone to intrigues. Burr senses Hamilton’s hand at work in these reversals.

The two are also on opposite sides in the political arena – Hamilton as staunch Federalist and Burr as a loyal Democratic-Republican. As such, they are forever sniping at each other, especially around New York state elections.

The stakes here go way up in 1791 when Burr runs for Senate against Hamilton’s father-in-law, General Phillip Schuyler. Burr’s tactics and victory seem to represent a final breach with Hamilton.

In 1795, Burr and fellow Democratic-Republican, James Monroe, apparently conspire to pull Hamilton down from his lofty perch as Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, by leaking the story of his affair with Maria Reynolds. This forces Hamilton to make an embarrassing public confession, and to resign from office.

Henceforth Hamilton will search for any and all opportunities to destroy Burr.

His first chance materializes in the election of 1800, when Burr and Jefferson end up tied on electoral votes for the presidency – and the final decision ends up in the Federalist controlled House of Representatives. Hamilton, of course, is unhappy with both options. But, on a 36th ballot, he uses his influence to elect Jefferson, as who he claims is “less dangerous than Burr…who loves nothing but himself.”

Jefferson’s convictions about Burr also sour during his first term, and he plans to seek a new Vice-President as the 1804 election approaches. Knowing this, Burr decides to run for Governor of New York against another Democratic-Republican, former Attorney General, Morgan Lewis. With no entry of their own in the running, some Federalists come out for Burr, until Hamilton steps in and quashes this movement.

Tensions between the two mount on April 24, when The Albany Register publishes a letter where a third party quotes Hamilton as calling Burr “a dangerous man…who ought not be trusted with the reins of government” and referencing “a still more despicable opinion which Mr. Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.”

Burr then loses the race for governor by a decisive 58% – 42% margin — effectively ending his hopes for high political office. Again he places much of the blame on Hamilton.

After the election, a series of increasingly tense exchanges occur between the two men in written notes, which lead on to a “challenge” from Burr, which Hamilton accepts.

Both men have been “called out” before on numerous occasions, all so far “resolved” without any shots being fired. But this time, the long-term hostility runs deep, and the duel unfolds.

It is set for July 11, 1804, at the Heights of Weehauken in New Jersey – a popular site for dueling, despite the fact that it is officially outlawed both there and in New York. The ground holds special meaning for Hamilton. On November 23, 1801, his 19 year old son, Philip, is shot dead here in a duel he has initiated in defense of his father’s name.

Be it premonition or not, the elder Hamilton writes out a will on July 10, the day before the duel. He states that he intends to “withhold his first fire,” and then addresses his wife:

Adieu best of wives and best of Women. Embrace all my darling Children for me. Ever yours, AH.

Around 7AM, Burr and Hamilton arrive by separate boats, rowed from mid-town Manhattan some three miles across the Hudson. Both men greet each other formally, Colonel Burr and General Hamilton, according to the code.

An area extending some ten paces is cleared, with Hamilton standing on one end, facing the Hudson, and Burr at the other, looking inland. Each man holds a .56 caliber pistol, provided by Hamilton, the same pair his deceased son used. The pistols are loaded by seconds in plain sight. The two combatants assume the classical positions –right foot forward, with bodies tucked sideways to present the smallest possible silhouette for targeting. Hamilton dons his glasses at the last second. The rules are then read aloud, as follows:

The parties being placed at their stations, the second who gives the word shall ask them whether they are ready; being answered in the affirmative, he shall say- present! After this the parties shall present and fire when they please. If one fires before the other, the opposite second shall say one, two, three, fire, and he shall then fire or lose his fire.

Hamilton’s second is chosen by lot to say the word present, which he does. Exactly what happens next is the subject of some debate. All accounts agree that both men fired, but who shot first is open to question. Some argue that Hamilton fired into the air, throwing away his attempt. A subsequent search for the ball finds it in a tree limb, some seven feet above and four feet wide of Burr’s position.

But Burr’s ball catches Hamilton above the right hip, fracturing a rib, slicing through his liver, and ending up lodged in lower vertebrae. Burr advances toward his fallen foe, but is quickly diverted by his seconds and leaves the scene.

Hamilton is in the arms of his second, Nathaniel Pendleton, when his medical man, Dr. Hosock, examines the wound and recognizes that it is mortal. Together the two men carry Hamilton, who remains conscious, to his boat, and row him back to Manhattan. He is put to bed and given heavy dose of laudanum for pain. He lives through the night and dies around 2PM the next day.

The nation is shocked by Hamilton’s death, and cries mount to put an end to dueling. Burr is indicted for murder and flees to South Carolina. But the case for retribution against duelists is not intense, and he returns to Washington, D.C. to serve out the remainder of his term as Vice President.

He will live in and out of the public spotlight for another 34 years after the events at Weehauken, and forced to flee to Europe for four years after being acquitted in a sensational 1807 trial for treason.