Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

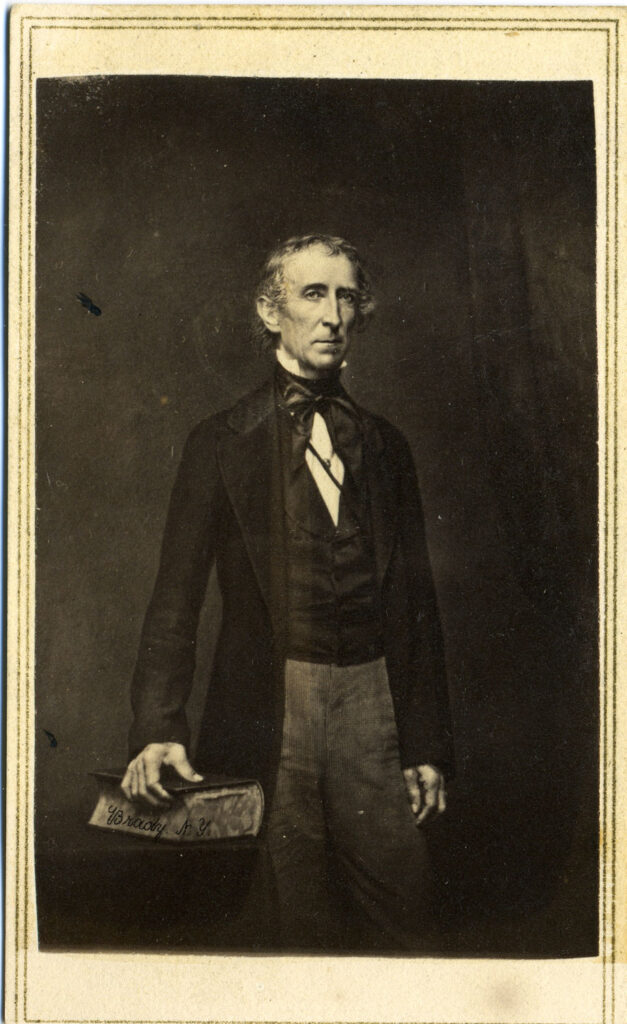

Chapter 98: John Tyler Completes The Presidential Term

April 6, 1839

Vice-President Tyler Claims The Oval Office

While the burial ceremonies proceed, Daniel Webster’s son, Fletcher, rides to Williamsburg, Virginia to inform John Tyler of Harrison’s death. The Vice-President is there because he has no responsibilities in Washington until the Senate reconvenes in June. But Tyler has received reports of Harrison’s illness and is poised to assert his claim to successor status. He makes a hasty journey to DC, arriving on April 6 to meet with the Cabinet and assume command.

At this point, a legal debate ensues, with opponents of Tyler arguing that he is merely the “Acting President,” serving until another election can be called to choose a permanent successor. They try to make their case around wording in the 1804 Twelfth Amendment which says the Vice-President shall “act as President” not “become” President.

If the House shall not choose a President…then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in the case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.

Tyler simply ignores the issue, plows forward and takes the oath of office, and at fifty-one years old becomes, de facto, the youngest man to serves so far as President.

Critics of Tyler like John Quincy Adams are immediately alarmed:

Tyler is a political sectarian, of the slave-driving, Virginian, Jeffersonian school, principled against all improvement, with all the interests and passions and vices of slavery rooted in his moral and political constitution — with talents not above mediocrity, and a spirit incapable of expansion to the dimensions of the station upon which he has been cast by the hand of Providence, unseen through the apparent agency of chance. No one ever thought of his being placed in the executive chair.

Henceforth opponents will refer to him with the snickering epithet “His Accidency.”

1790 – 1862

President John Tyler Personal Profile

John Tyler grows up on “Greenway” plantation, a 1200 acre estate on James River that relies on slaves to grow tobacco.

His father, “Judge” John Tyler Sr., serves in the Continental Army but opposes the Constitution on grounds that it limits state’s rights and disadvantages the South. As Governor of Virginia (1808-1811) he remains a staunch anti-Federalist. He is also a friend of Thomas Jefferson, who often dines at Greenway with the Judge and his son.

Young Tyler is a precocious student and graduates from the College of William & Mary at 17 years of age, and passes the bar at nineteen. By 1811 he has built his own reputation as a criminal defense attorney and, through his connections, is elected to Virginia’s House of Delegates. He joins the militia during the War of 1812, but sees no action. In 1813 Tyler inherits Greenway upon the death of his father, then marries the beautiful but reclusive Letitia Christian, who also brings her own wealth to the union.

He is elected to the U.S. House at age twenty-six, and remains there from 1816-1821, consistently voting against Henry Clay’s attempts to build the nation’s infrastructure, pass protective tariffs and establish a strong central bank. His views on slavery are those of the aristocratic planters – a stated moral discomfort with the practice, followed by rationalization of its necessity, additions to his personal ownership, and some vague wish to see it wither away over time. In line with these views, he votes against the Missouri Compromise of 1820 for imposing what he considers an illegal constraint on the spread of slavery into the west.

By no stretch of the imagination do his thoughts or votes to this point peg him as a future Whig supporter!

Tyler abandons Congress in 1821, frustrated by what he considers the constant erosion of states’ rights. He returns home to Virginia, but is soon bored by farming and jumps back into politics, serving as Governor from 1825 to 1827. After that, he returns to DC and the U.S. Senate in 1827, replacing the unhinged John Randolph and proclaiming himself a Jackson Democrat.

But he turns against Jackson in 1833 during the Nullification Crisis. He views the “Force Bill,” aimed at blocking South Carolina secession, as one more overreach by the federal government against the sovereign wishes of the states. His is the only Southern Democrat “no vote” in the Senate on the measure.

A year later, he has flipped his support over to Henry Clay, almost as a “lesser evil” than Jackson. When he sides with Clay to “censure” Jackson for removing funds from the U.S. Bank, the legislature in Virginia orders him to reverse his course. This leads him to resign his seat in 1836.

At this point, Clay and the Whigs begin to view Tyler as a handy political pawn in their scheme to defeat the Democrats.

He plays along with this in the 1836 election, running as a Vice-Presidential candidate on two of the four Whig “regional tickets” designed to deny Van Buren an outright victory and throw the final choice into the House. His role is to attract Southern votes, based on his status as a Virginian, a slave owner, and an opponent of a “too powerful” Executive.

While Van Buren wins in 1836, Tyler is henceforth viewed as an affable “go-along” politician, one who could pass as a Southern Whig – despite his early ties to the opposition.

It is this shallow assessment which causes the weary Whig delegates at the December convention to select Tyler to run as Vice-President, after three “Clay men” have turned the offer down.

At that moment, none recognize that the “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” union will backfire when Harrison dies and a true “closet Democrat” replaces him in the White House.

April 9, 1841

Tyler’s Message To The Nation

On April 9, Tyler issues a brief message outlining some thoughts about his presidency. He begins by acknowledging the unique circumstances leading to his position, and the potential for attacks based on the “spirit of faction.”

For the first time in our history the person elected to the Vice-Presidency of the United States, by the happening of a contingency provided for in the Constitution, has had devolved upon him the Presidential office. The spirit of faction, which is directly opposed to the spirit of a lofty patriotism, may find in this occasion for assaults upon my Administration.

Instead of a full inaugural address he says he will offer…

A brief exposition of the principles which will govern me in the general course of my administration of public affairs (which) would seem to be due as well to myself as to you.

He begins with foreign affairs, possibly anticipating tensions between Mexico and the Republic of Texas.

In regard to foreign nations, the groundwork of my policy will be justice on our part to all, submitting to injustice from none. While I shall sedulously cultivate the relations of peace and amity with one and all, it will be my most imperative duty to see that the honor of the country shall sustain no blemish.

He then expresses concerns over the “spoils system” (i.e. patronage) that so troubled him about both the Jackson and Van Buren administrations. His reference to “removals from office” may portend future changes he has in mind for the cabinet inherited from Harrison.

The patronage incident to the Presidential office, already great, is constantly increasing…I will at a proper time invoke the action of Congress upon this subject, and shall readily acquiesce in the adoption of all proper measures which are calculated to arrest these evils, so full of danger in their tendency. I will remove no incumbent from office who has faithfully and honestly acquitted himself of the duties of his office, except in such cases where such officer has been guilty of an active partisanship or by secret means… I have dwelt the longer upon this subject because removals from office are likely often to arise, and I would have my countrymen to understand the principle of the Executive action.

He shifts to financial management, promising to avoid public debt in time of peace, and then to end the “war between the Government and the currency” – an evident reference to Jackson’s distrust of soft money.

In all public expenditures the most rigid economy should be resorted to, and, as one of its results, a public debt in time of peace be sedulously avoided. A strict responsibility on the part of all the agents of the Government should be maintained and peculation or defalcation visited with immediate expulsion from office and the most condign punishment.

The public interest also demands that if any war has existed between the Government and the currency it shall cease… I shall promptly give my sanction to any constitutional measure which, originating in Congress, shall have for its object the restoration of a sound circulating medium, so essentially necessary to give confidence in all the transactions of life…

In regard to familiar tensions between state and federal sovereignty, he will be the strict constructionist, “abstain(ing) from all attempts to enlarge the range of powers…granted…the Government,” since to do otherwise would “break asunder the bond of union…or end in a bloody scepter and iron crown.”

Those who are charged with its administration should carefully abstain from all attempts to enlarge the range of powers thus granted to the several departments of the Government other than by an appeal to the people for additional grants, lest by so doing they disturb that balance which the patriots and statesmen who framed the Constitution designed to establish between the Federal Government and the States composing the Union.

The observance of these rules is enjoined upon us by that feeling of reverence and affection which finds a place in the heart of every patriot for the preservation of union and the blessings of union….An opposite course could not fail to generate factions intent upon the gratification of their selfish ends, to give birth to local and sectional jealousies, and to ultimate either in breaking asunder the bonds of union or in building up a central system which would inevitably end in a bloody scepter and an iron crown.

With those vague and wandering guidelines on the record, Tyler begins his controversial four year term.

1841-1845

Overview Of Tyler’s Term

Tyler’s term will prove both controversial and consequential regarding America’s future destiny.

After being sworn in, the assumption throughout the capital is that the “Accidental President” will bend his will to the hierarchy within the Whig Party. As Preston Blair, editor of the Democrat’s newspaper The Washington Globe, puts it: Tyler will be “Clay’s pliant tool” in the White House.

But Clay is not the only one seeking control, as Tyler finds out when his inherited cabinet tells him of Harrison’s intent to count their votes as equal to his on policy decisions. His response sets the tone for what is soon to follow:

I am very glad to have in my cabinet such able statesmen…and I shall be pleased to avail myself of your counsel and advice. But I can never consent to being dictated to. I am the President and I shall be responsible for my administration.

From then on, Tyler shows his true political colors as a states’ rights Democrat and a slave holder.

He immediately frustrates Clay’s attempt to create another Federal Banks to fund the Whig’s infrastructure projects. In response, they gather and officially oust him from the Party, then follow by hurling rocks at the White House terrifying his stroke-ridden wife, Leticia, and leading to a police patrol to guard the property.

From there they do their best to frustrate every move he makes. On three occasions, the Senate refuses to confirm Caleb Cushing – a Whig who stays loyal to Tyler – as Secretary of the Treasury. They also turn away all four of his Supreme Court nominees.

Still Tyler’s term witnesses a series of events that will dramatically heighten the sectional tensions over slavery and eventually set the stage for war.

First is an increase in the number of Northerners who are at least “troubled” by the notion of human bondage. This feeling is sparked during the “religious awakening” phase, with its calls for moral perfection and social reform. It is broadened by agitation from abolitionists like Garrison and his formation of organized anti-slavery societies. Then it’s carried into the political arena by the likes of J.Q. Adams and Joshua Giddings in Congress, and philanthropists Gerrit Smith and the Tappan brothers with their Liberty Party.

This draws a response from the South with clergyman James Henley Thornwell arguing that slavery is “ordained by the Bible” — a claim that provokes heated disputes within the three main Protestant Churches and ends with ominous North-South doctrinal schisms.

Tyler also encounters more ongoing challenges to the Fugitive Slave Act. One involves a mutiny aboard the American ship Creole, which ends with some 135 slaves being freed in Nassau by a British court. This act, along with other at sea and border disputes, threatens warfare, until resolved by the Ashburton-Webster Treaty of 1842. A second controversy involves a female slave who ends up living in Pennsylvania and sues for her release under the theory of “once free, forever free.” Much to the dismay of the abolitionists, this notion is dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark Prigg v Pennsylvania decision.

Finally, it is during Tyler’s term that Americans become enamored with the notion of “Manifest Destiny,” the idea that its borders should extend all the way to the Pacific Ocean, across territory currently owned by Mexico. This leads to a series of exploratory expeditions by the Army Corps of Engineers and Lt. John C. Fremont to produce accurate maps of the Oregon Trail and the coast of California. His lyrical descriptions of these journeys are an overnight sensation and heighten public support for westward expansion, beginning with the annexation of Texas – a fateful move that Tyler supports and that eventually leads to the Mexican War and re-opens the toxic debate over slavery.

On the economic front, the economic depression Tyler inherits from Van Buren continues to plague the nation up to 1844, when some signs of recovery appear.

Economic Overview: John Tyler’s Term

| GDP | 1840 | 1841 | 1842 | 1843 | 1844 |

| Total ($MM) | 1574 | 1652 | 1618 | $1550 | $169 |

| % Change | (5%) | 5% | (2%) | (4%) | 9% |

| Per Cap | 92 | 94 | 89 | $83 | $88 |

John Tyler is 54 years old when his term ends. He reflects on his “accidental presidency” in brief remarks on his last day in the White House:

In 1840 I was called from my farm to undertake the administration of affairs, and I foresaw that I was called to a bed of thorns…I rely on future history, and on the candid and impartial judgment of my fellow citizens, to award me the meed due to honest and conscientious purposes to serve my country.

The ex-President will live on for another 15 years, mostly at his Virginia plantation, “Sherwood Forest.” One of his remaining joys will be his youthful new bride Julia, whom he marries in June 1844, after losing his first wife Leticia in September 1842. Together they will have seven children to go along with the eight Tyler fathered before.

As the threat of war reaches a boiling point in April 1861, Tyler returns to Washington to sponsor the Virginia Peace Conference, which fails to find a compromise. At that point, he goes with his home state, Virginia and is elected to the CSA House, but dies on January 18, 1862, before its opening session.

Key Events: Tyler’s Term

| 1841 | |

| April 4 | President Harrison dies after 31 days; Tyler is first to succeed as Vice President |

| April 10 | Horace Greeley begins to publish his pro-Whig and anti-slavery New York Tribune |

| August 6 | Congress passes Whig’s Fiscal Bank Bill (similar to Bank of US) |

| August 11 | Frederick Douglass addresses an Anti-Slavery meeting in Nantucket |

| August 13 | Congress repeals Van Buren’s Independent Treasury Act |

| August 16 | Tyler vetoes Whig’s Fiscal Bank Bill as unconstitutional |

| September 2-3 | Another race riot breaks out in Cincinnati |

| September 3 | Congress passes revised Fiscal Bank Bill to address Tyler’s concerns |

| September 9 | Tyler vetoes the new bill and attempt to override veto voted down in Senate |

| September 11 | Tyler’s cabinet resigns en masse, all except for Sec. of State Daniel Webster |

| November 7- 9 | Slaves on Creole, going from Va. to New Orleans, kill crew & are freed in Nassau |

| Year | George Ripley starts up his Brook Farm utopian community |

| 1842 | |

| January 24 | JQ Adams presents Haverill, Mass petition or peaceful dissolution of the Union |

| March 1 | Supreme Court in Prigg v Commonwealth of Pa says that the state cannot forbid seizure of run-away slaves – but says enforcement is left up to the state, not fed |

| March 21-23 | Abolitionist Joshua Giddings censured in House for supporting escape of Creole slaves & opposing all shipping of slaves in US waters; he resigns his seat on Mar 23 |

| March 30 | Highly protective Tariff of 1842 passes Whig controlled Congress |

| March 31 | Henry Clay resigns from Senate to prepare run for White House; Martin Van Buren also sees opportunity to succeed Tyler. |

| March | Mass Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw rules that a union is legal org. & may strike |

| April | Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton arrives to negotiate US-UK issues |

| May | John C. Fremont embarks on first expedition to the Rocky Mountains |

| June 10 | Lt. Charles Wilkes returns from 4 year 90,000 mile voyage across Asia Pacific |

| August 9 | Webster, Tyler and Ashburton agree on a US-UK Treaty |

| August 29 | The Senate approves the Webster-Ashburton Treaty |

| September 10 | First Lady Leticia Tyler dies at the White House |

| September 11 | Mexican soldiers invade Republic Of Texas & capture San Antonio |

| October 20 | Va. run-away slave, George Latimer, arrested in Boston |

| Fall | Fremont returns from his successful mapping expedition to the South Pass Whigs suffer massive losses in Congress in mid-term elections |

| 1843 | |

| May 8 | Daniel Wester resigns as Secretary of State |

| May 22 | Large band of settlers head from Missouri to Oregon territory |

| May | Fremont leaves Missouri on expedition to Columbia River and California |

| July 24 | Abel Upshaw confirmed as Secretary of State |

| August 14 | Second Seminole War ends in Florida |

| August 23 | Mexican President Santa Anna warns US that annexation of Texas would lead to war |

| August 30-31 | Abolitionist Liberty Party nominates James Birney for President |

| Year | Vermont state assembly votes to ignore Fugitive Slave Act |

| 1844 | |

| March 6 | John C. Calhoun becomes Sec. of State, after Abel Upshur killed in ship explosion |

| March | Fremont expedition arrives in Sacramento |

| April 4 | Fourierist socialist organization elects George Ripley (Brook Farm) as President |

| April 12 | Tyler signs Texas Annexation negotiated by Calhoun & submits to Senate |

| April 27 | Both Clay and van Buren publicly oppose Texas Annexation |

| May 1 | Whigs nominate ticket of Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen |

| May 6-8 | Violent clash between Catholics & Protestants in Philadelphia, with 20 killed |

| May 27-29 | Democrats reject Van Buren & nominate dark-horse James Polk, backed by Jackson |

| June 8 | Senate rejects Texas Annexation Treaty |

| June 27 | Mormon leader Joseph Smith murdered in Nauvoo, IL |

| December 3 | House repeals 1836 Gag Rule in response to JQ Adams calls |

| December 4 | Polk defeats Clay for presidency |

| Year | Baptist Church splits North vs. South over ownership of slaves by members |

| 1845 | |

| February 28 | Congress “resolution” (not a 2/3rds majority treaty) annexes Texas |

| March 3 | Florida admitted to Union as 27th state |

| March 4 | Polk is inaugurated |