Section #16 - Open warfare in “Bloody Kansas” follows fraudulent election wins for Pro-Slave State forces

Chapter 190: Know Nothings And Catholics Battle On “Bloody Monday” In Louisville

1845 Forward

Resistance To Catholic Immigrants Increases

By 1850, the number of foreign born residents reaches 2.24 million or 9.7% of the total population – up from only 4.6% a decade earlier.

Most of the immigrants end up in major cities in the North, and often inland from the east coast. Milwaukee, Chicago, St. Louis and Cincinnati all have foreign born representation in the 50% plus range as of 1850.

Presence Of Foreign-Born Residents In Some U.S. Cities: 1850 Census (000)

| Native Born | Foreign Born | Total | % Foreign Born | |

| Milwaukee | 7.2 | 12.8 | 20.0 | 64% |

| Chicago | 13.7 | 15.7 | 29.4 | 53 |

| St. Louis | 36.5 | 38.4 | 74.9 | 51 |

| New Orleans | 50.5 | 48.6 | 99.1 | 49 |

| Cincinnati | 60.6 | 54.5 | 115.1 | 47 |

| New York | 277.8 | 235.7 | 513.5 | 46 |

| Albany | 31.2 | 16.6 | 47.8 | 35 |

| Boston | 88.9 | 46.7 | 135.6 | 34 |

| Louisville | 25.1 | 12.5 | 37.6 | 33 |

| Newark | 26.6 | 12.3 | 38.9 | 32 |

| Philadelphia | 286.3 | 121.7 | 408.0 | 30 |

| Providence | 31.8 | 9.7 | 41.5 | 23 |

| Baltimore | 130.5 | 35.5 | 166.0 | 21 |

| Charleston | 17.8 | 4.6 | 22.4 | 20 |

| Richmond | 15.5 | 2.1 | 17.6 | 12 |

| Washington | 33.5 | 4.3 | 37.8 | 11 |

Most arrive with the usual set of challenges facing immigrants to a new land. They are typically impoverished, with only the possessions they can carry on their long ocean voyage, and many speak no English. But above and beyond those drawbacks, the vast majority have an additional stigma, their membership in the Roman Catholic Church.

It is one thing for many Americans to accommodate freedom of religion across a wide range of Protestant sects, but quite another to overlook three hundred years of old-world hostilities against the Church of Rome.

In large part, this anti-Catholic heritage fuels the growth of the Know Nothing Party and the kind of mob violence that flares up, beginning in 1844 in the Philadelphia riots.

In the summer of 1855, it again explodes in Louisville, Kentucky, pitting the nativists against the city’s Catholic population, in this case, mainly Germans by birth.

August 6, 1855

Election Day Violence Pits Nativists Against Catholic Immigrants

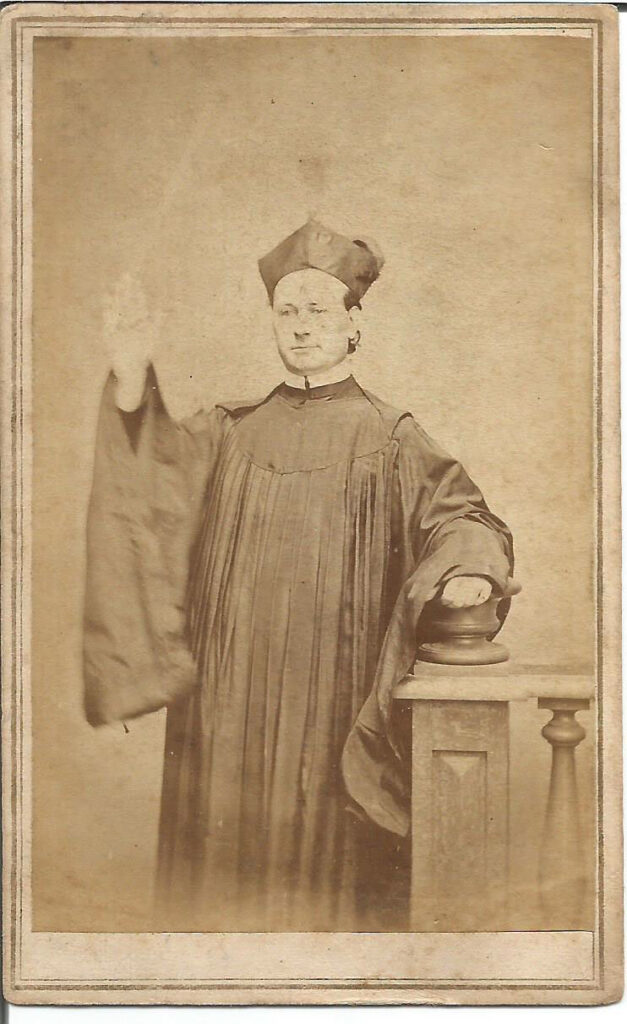

The Catholic Diocese of Louisville encompasses the entire state of Kentucky and is extensive in scope, with some fifty-six churches, eighty-six chapels and the clergymen required to support them.

Public antagonism toward the Catholics is endemic, but it intensifies when they lobby for controversial reforms, especially related to use of the King James Bible in public schools, oath-taking, and other civic and governmental ceremonies.

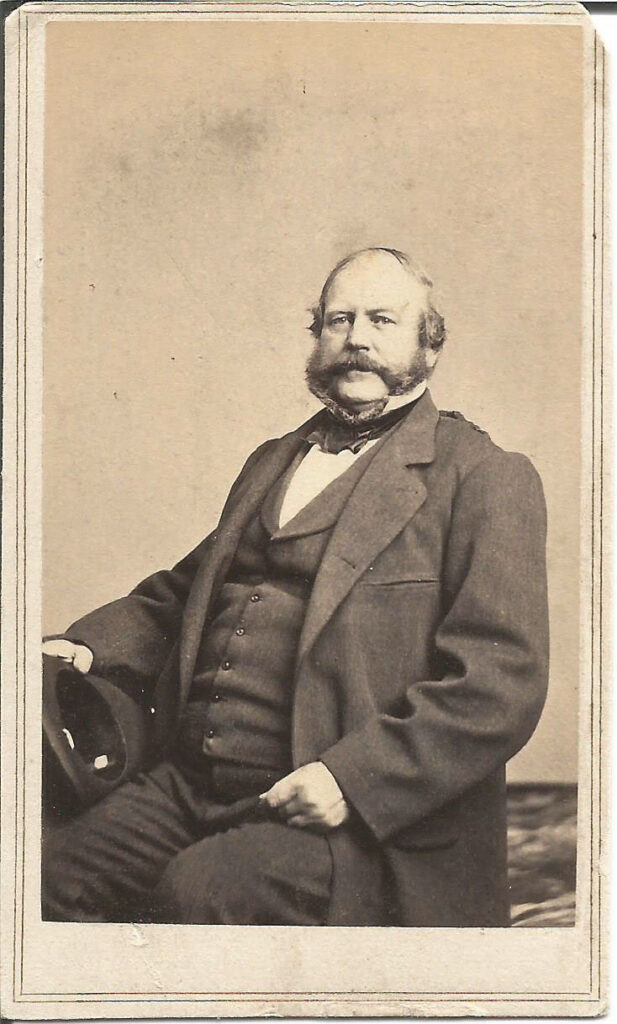

Many opponents are also convinced that the Catholics are not loyal citizens, that their allegiance to the Pope outweighs their commitment to the United States. This idea is put forth by George Prentice, editor of the influential Louisville Daily Journal, who tells his readers in July 1855 that:

It is necessary for salvation that everyone be subject to the Roman Pontiff.

The Know Nothing resistance springs into public view in Louisville around mid-year in 1854, with members sporting a metallic eagle insignia pinned to their left breast on their way to secret meetings.

In response to the rise of these Know Nothing lodges, a German version known as the “Sag Nichts” (say nothing) is formed. It rejects all forms of nativism and attempts to reduce the period required for naturalization.

The first signs of physical violence between the two camps appear when fistfights break out at polling places during city and county elections held in August, 1854. Some, however, attribute these to traditional politics, the old-line Louisville Whigs battling their Democratic foes, the party of the Catholics.

A year later, on Monday, August 6, 1855, the race for Governor of Kentucky matches the Know Nothing candidate, plantation owner and ex-Whig, Charles Morehead, against the Democrat, Beverley Clarke.

Initial confrontations between Know Nothings and Sag Nichts bands materialize through-out the week leading up to the election. On the day of the polling, Prentice’s Louisville Daily Journal fires up nativist supporters in its editorial:

Fellow citizens: shall the shouts of triumph that echo through our streets tonight, be raised by American voices or shall they resound in the harsh tones of Germanv and Ireland?

The Daily Democrat volleys back with accusations that the nativists plan to steal the election through violence.

The dam bursts on “Bloody Monday” as the two sides go to war in the streets of Louisville.

Strong-arm methods at polling sites by Know-Nothings are countered by Catholics, and both sides are soon shooting at each other. Even a bolstered police force is unable to halt the battles. Houses are burned and shops are looted. Former Congressman William Thommason is beaten and Father Karl Boeswald is fatally injured by thrown stones. In all, hundreds are injured and the death toll ranges upwards from twenty-two on the day.

As in the Philadelphia riots, attempts are made to destroy Catholic churches. Fierce fighting occurs around St. Martin of Tours and the Cathedral of the Assumption before the Know Nothing Mayor of Louisville, John Barbee, steps forth to quell the mobs.

A German diarist captures the ferocity of the day:

Reckless youths, who had been active in these things, spoke of their deeds in terms of levity that were shocking. They said that they did not know how many they had killed but that they had popped down every Irishman they saw. Half-grown boys, rendered perfectly devilish with ungoverned passion and whiskey, filled the streets with yells and violence. Christian men and women alike, becoming demons, urged on the young men. Most painful sights were witnessed. Poor women were fleeing with their children and little mementos of home that were brought from the Fatherland. The most painful of all sights was the stars and stripes waved at the head of the sacrilegious mobites.

Almost forgotten in the chaos is the election itself, which goes to the Know-Nothing, Moreland by a narrow statewide margin of 69,816 to 65,413. In Louisville, none of the rioters on either side are ever prosecuted.