Section #1 - America’s years as a British Colony end with The Revolutionary War

Chapter 3: The Reformation & The Enlightenment Challenge Entrenched Institutions

1517 Forward

Luther Protests Catholic Church Doctrines

The period leading up to the settlement of the British colonies in America is marked by a series of challenges to the heretofore unquestioned authority of both the Church and the Crown. In 1517, a German monk named Martin Luther, nails his 95 Theses on the door of the All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Saxony protesting the notion that paying indulgences to the clergy can insure one’s eternal salvation.

What follows Luther’s act is the great religious schism known as the Protestant Reformation.

It takes hold across the 16th century and intersects with affairs of state in 1527 when Pope Clement VI refuses to grant a marriage annulment to King Henry.

Exercising his “divine right” as monarch, Henry responds by banishing the existing Catholic Church and replacing it with his own Church of England.

This ends the monolithic dominance of Catholicism in Britain and across much of Europe.

1642-1660

The English Civil Wars Challenge The Monarchy

The 17th century also ushers in early resistance to the despotic rule of hereditary Monarchies.

A principal figure here is King Charles I of England who exercises the “divine right of kings” to tax the people at will and marry a queen who is both French and Catholic.

After almost 25 years of his affronts, a Parliamentarian movement rises up – under the Puritan leader, Oliver Cromwell – that leads to the First English Civil War beginning in 1642. Cromwell’s “Roundheads” (for their bowl-cut hairdos) defeat the Royalists on May 5, 1646.

After a series of failed attempts to rally his forces and regain the throne, Charles is captured and tried for treason.

1689-1789

Enlightenment Philosophers Explore New Forms Of Governance

Following on the heels of the English Civil Wars comes another revolutionary phase known as The Enlightenment or the Age of Reason. Its focus is again on the Monarchy and challenges to the notion that Kings have the divine right to absolute power over the lives of the citizenry.

Grave of Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

Grave of Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)Four leading philosophers of The Enlightenment argue the time has come for new forms of government that respond to the will of the people.

The English philosopher and physician, John Locke (1632-1704), lives through the turmoil after Cromwell’s death in 1658 and the restoration of Charles II, whose reign includes the Black Plague, the Great Fire of London, and a deathbed conversion to Catholicism. When his son James II marries a Catholic, another popular rebellion places the Protestant William III of Orange and his wife Mary back on the throne. As part of the deal, the pair agree to a “Declaration of Rights” which limits the power

of the crown over its subject.

In 1689, as William and Mary ascend, Locke publishes his “Second Treatise of Government” in which he argues on behalf of “classical liberalism” — that the size and power of government should be limited in order to preserve and enlarge the freedom

The end of law…is to preserve and enlarge freedom.

- The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason is that law.

- The natural liberty of man is to be free from any superior power on earth. • All mankind, being equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions.

- Men being by nature, all free, equal, and independent, no one can be subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.

Locke’s preferred form of government is a monarchy, but he demands that it be “constitutional” in nature, with all property owners given the right to vote.

The Swiss writer and musician, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), grows up in a middle class family in Geneva, leads a bohemian lifestyle, and records his observations about the nature of man and society in a series of tracts that challenge conventional thought. He asserts that men are born free, equal and happy and then surrender these joys by entering into a destructive social contract based on property rights.

The first person who, having enclosed a plot of land, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human race have been spared, had someone pulled up the stakes or cried out to his fellow men: “Do not listen to this imposter. You are lost if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong to all and the earth to no one!”

According to Rousseau, governments, especially monarchies, are typically dedicated to protecting the property rights of the haves at the expense of the have-nots, who are left in chains. The only way around this are laws that balance out the score.

In truth, laws are always useful to those with possessions and harmful to those who have nothing; from which it follows that the social state is advantageous to men only when all possess something and none has too much.

The path to just laws lies in forming a government based on “pure Democracy” where decisions are arrived at in open debate, with full participation on all sides, and a final vote based on “majority rules.” In this regard, the English system – a “Republic,” where lawmakers are elected to represent their constituencies – falls short of Rousseau’s ideal.

The people of England regards itself as free; but it is grossly mistaken; it is free only during the election of members of parliament. As soon as they are elected, slavery overtakes it, and it is nothing.

Needless to say, Rousseau is regarded as a dangerous radical by the establishment, and his works are banned in the Calvinistic canton of Geneva. Still, his populist views will fuel reformers on behalf of Democracy.

Two other Enlightenment thinkers also weigh heavily in the search for options to the absolute monarchies.

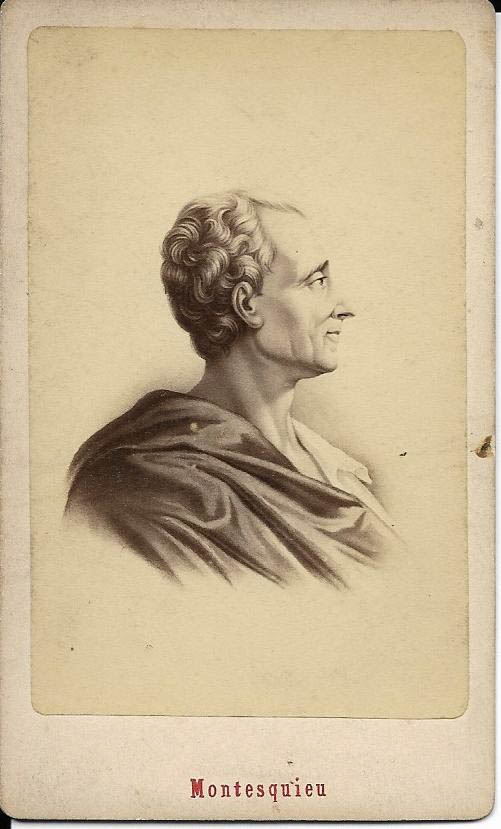

The Scottish essayist, David Hume (1711-1778), focuses on two essential ingredients – unfettered free speech and a written, formally approved Constitution. The French Baron and lawyer, Charles Montesquieu (1689-1775), calls for dividing government into separate branches to insure “checks and balances” on major decisions and to prevent concentrations of power.

(1689-1775)

But unlike Rousseau, both Hume and Montesquieu fear that “direct Democracy” will trample on the rights of minority interests. Protecting these interests, they feel, requires a “Republican” government, with elected statement using personal judgment and wisdom to guard against unbridled “majority rules.” In the end, all four of the Enlightenment thinkers and writers will play a significant role in shaping the beliefs of the American colonists about the full range of institutions they choose to create.