Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 212: The Dred Scott Decision Further Divides The Nation

February 1856

The Dred Scott Case Arrives At The U.S. Supreme Court

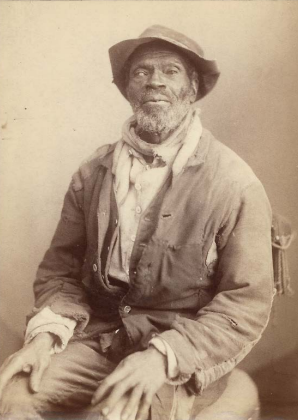

Dred Scott is thought to be 61 years old when the story of his enslavement and quest for freedom reaches the United States Supreme Court and the front page headlines of newspapers across the nation.

Born into slavery in Virginia in 1799, Scott eventually moves with his master, Peter Blow, to St. Louis. In 1832, he learns that he is being sold to Dr. John Emerson, an army surgeon, and tries unsuccessfully to run away. Emerson subsequently takes Scott along with him on two transfers of duty, both times into Free States: first, in 1834-35 to Rock Island, Illinois; then in 1836 to Ft. Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory, above the 36’30” freedom line.

Emerson clearly befriends Scott, “allows” him to marry another of his slaves, Harriett, and then to stay behind at Ft. Snelling on his own after the doctor is transferred back to St. Louis and then to Ft. Jessup, Louisiana. But in 1838 the Scotts rejoin Dr. Emerson voluntarily at Ft. Jessup, to act as household servants.

When Emerson dies in St. Louis in 1843, his widow, Irene, inherits the Scotts, and hires them out for wages to various acquaintances, one being Henry Blow (son of Peter), a friend of Scott during his childhood, and an anti-slavery activist. Blow learns that Scott and his wife, now with two children, have tried to purchase their freedom for $300, but Irene refuses to go along. Blow steps in to help Scott, filing a suit in the St. Louis Circuit Court against Irene Emerson on August 6, 1846. It asserts that the Scotts were no longer enslaved the minute they took up residence with Dr. Emerson in Illinois and Wisconsin – under the Commonwealth v Aves precedent of “once free, forever free.”

What follows on is an eleven year legal odyssey, marked by technical delays, lower court judgments, appeals and reversals, refilings and retrials. Scott’s support throughout comes from a string of abolitionist lawyers who regard the effort as a cause celebre, to sustain the Aves case law principle.

In January 1850, the Scotts are finally declared free by the St. Louis District Court, only to find the decision reversed in 1852 by the Missouri Supreme Court. In 1853, Irene Emerson transfers their ownership to her brother, John Sanford, who the Scott’s take to the court in 1854 on a federal charge of “wrongful imprisonment,” seeking freedom and $16,500 in damages.

This latest charge is a tactic designed to transfer authority away from the Missouri state courts and, eventually, to the U.S. Supreme Court. This works, and the highest court agrees to hear the case in 1856.

Key Events: The Dred Scott Case

| April 6, 1846 | St. Louis Circuit agrees to hear Scott’s case brought by Henry Blow’s lawyers |

| June 1847 | Case dismissed on a technicality (no witnesses affirming Scott owned by Mrs. Emerson) |

| December 1847 | Scott appeals and is given permission to bring suit and Mrs. Emerson protests |

| June 1848 | MO Supreme Court allows Scott to proceed with his suit in Circuit Court |

| January 1850 | St. Louis Circuit Court says Scott was free due to his residency in a free state |

| 1852 | MO Supreme Court overrules the Circuit Court decision to free Scott |

| 1853 | Ownership of Scott transferred to Mrs. Emerson’s brother, John Sanford |

| 1854 | Scott sues Sanford in US Circuit Court for wrongful imprisonment, a federal offense |

| May 1854 | Federal District Court rules against Scott |

| December 1854 | Scott appeals to US Supreme Court |

| February 1856 | Oral arguments presented, but the Court orders a re-hearing after the 1856 election |

| December 1856 | The second hearings take place December 15-18 |

| March 7, 1857 | Final U.S. Supreme Court ruling delivered |

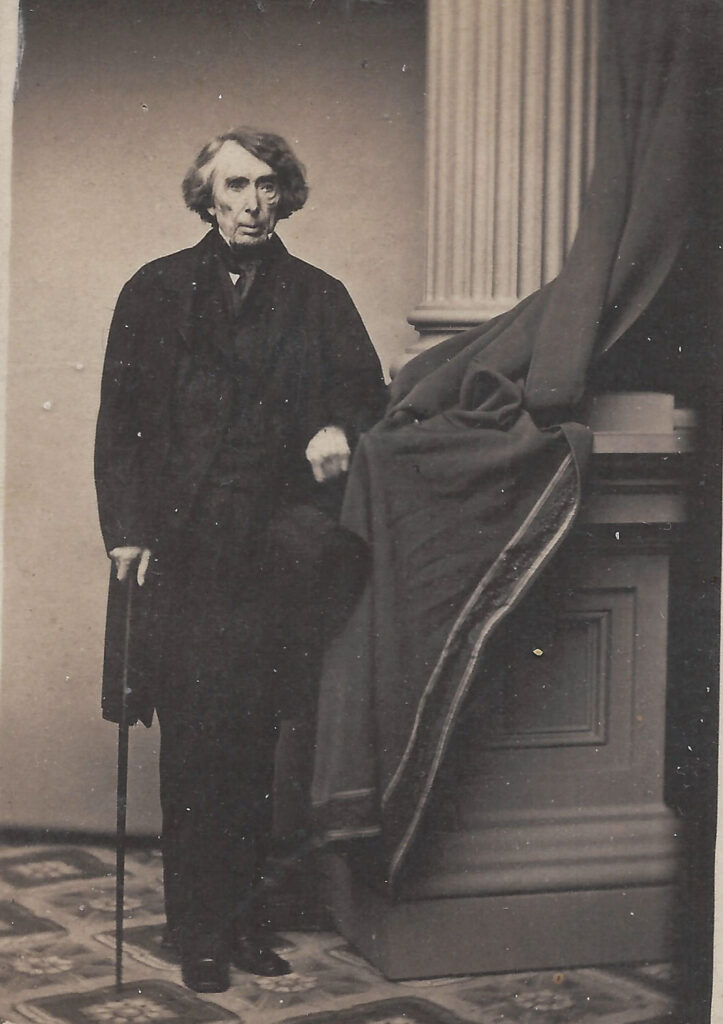

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and his eight associates hear the first oral arguments on February 11-14, 1856, roughly ten years after the first filing in April 1846.

Sidebar: The Taney Court During The Dred Scott Decision

The nine men who will judge Dred Scott are 64 years of age on average, the oldest being Chief Justice Taney at 80, the youngest, John Campbell at forty-six. Their mean tenure on the court is 16 years.

Two have “read law” on their own, while the remaining seven attended formal universities. Both Taney and Robert Grier have graduated from Dickinson College, Buchanan’s alma mater.

Three have military experience — James Wayne and John Catron having fought in the War of 1812, and John Campbell, a graduate of West Point, battling the Creek Indians in 1836.

Peter Daniel is the lone duelist, mortally wounding one John Seddon over a political dispute in 1808.

Taney and McLean are not only judicial giants, but also deeply involved in mainstream politics. Taney has served in Andrew Jackson’s cabinet, as Attorney General and as Secretary of War and of the Treasury. McLean has not held public office, although in 1856 he becomes a Republican, and receives 37 votes for president on the opening ballot at the party convention.

Four of the justices are nominated by Andrew Jackson, and, with the exception of Benjamin Curtis and McLean, all are lifelong Democrats. Six have entered the court by acclamation of the Senate, with only Taney and John Catron encountering significant opposition.

Of great significance in the Dred Scott case is the fact that five judges are from the South, and all of them are slave owners! John Catron of Tennessee is even known to have fathered a child by one of his charges.

This Southern pro-slavery tilt on the court is thought to have influenced Buchanan to inappropriately approach Robert Grier – a fellow Pennsylvania and Dickinson man – in search of a Northerner to support the majority opinion in the case.

By the time the Civil War breaks out, seven of the nine “Dred Scott justices” are still on the court, after Benjamin Curtis resigns in 1857 to protest the decision and Peter Daniels dies in 1860. Interestingly all who are left in 1861 oppose secession, and only one, Joseph Campbell, moves back south, eventually serving the Confederate cause as Assistant Secretary of War.

Supreme Court In 1857

| Born | Home | Nom. By | Vote | Party | Serve | Education | |

| John McLean* | 1785 | Ohio | Jackson | All | Dem/Rep | 1829-61 | Read law |

| James Wayne | 1790 | Georgia | Jackson | All | Democrat | 1835-67 | Princeton |

| Roger Taney | 1777 | Maryland | Jackson | 29- 15 | Democrat | 1836-64 | Dickinson |

| John Catron | 1786 | Tenn | Jackson | 28- 15 | Democrat | 1837-65 | Read law |

| Peter Daniel | 1784 | Virginia | Van Buren | 25-5 | Democrat | 1841-60 | Princeton |

| Samuel Nelson | 1792 | NY | Tyler | All | Democrat | 1845-72 | Middlebury |

| Robert Grier | 1794 | Penn. | Polk | All | Democrat | 1846-70 | Dickinson |

| Benjamin Curtis* | 1809 | Mass | Fillmore | All | Whig | 1851- 57 | Harvard |

| John Campbell | 1811 | Alabama | Pierce | All | Democrat | 1853-61 | West Point |

February to December 1856

Oral Arguments In The Case Are Presented Twice

Dred Scott v Sanford (often misspelled as Sandford) will be argued twice before the Taney Supreme Court, first in February 1856, and then a second time in December 1856.

The oral arguments are made by two outstanding advocates, well known for their legal prowess.

The plaintiff Scott is represented by Montgomery Blair, forty-two years old, a graduate of West Point, who opens his law practice in St. Louis before moving to Maryland. He is the eldest son of Frances Preston Blair, formerly a member of Andrew Jackson’s “kitchen cabinet,” who abandons the Democrats over the Kansas-Nebraska Act and, in 1855, becomes a founder of the Republican Party. Like his father, Montgomery wants to see slavery wither away in America, even though he feels that blacks are an inferior race, and that the abolitionist’s call for immediate freedom is illegal and radical.

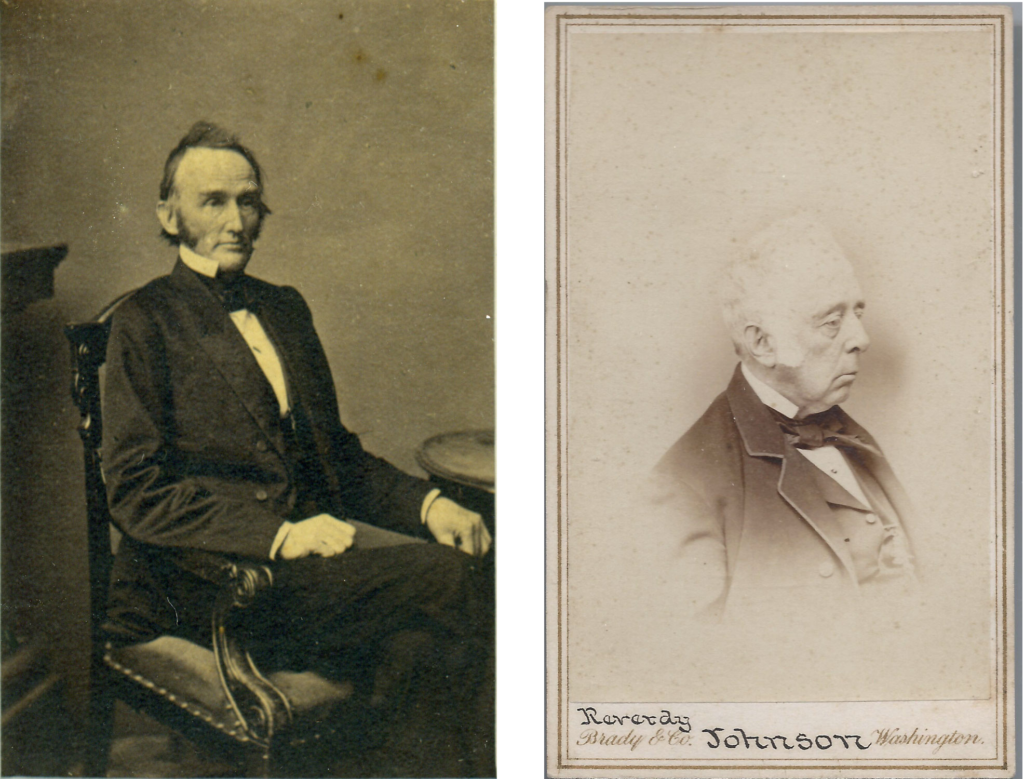

Blair is opposed by another famous Maryland attorney, fifty-nine year old, Reverdy Johnson, whose personal friendship with now Chief Justice Roger Taney goes back to 1815, when Johnson was just beginning his law career. That career has also taken him into politics, where he has served in the U.S. Senate as a Whig from 1845-49 before becoming Zachary Taylor’s Attorney General. Like Blair, Johnson personally opposes slavery and is also a strong pro-Union man.

After both advocates present their cases on February 11-14, 1856, the nine justices confer and appear ready to decide that the Missouri Supreme Court should have the last word on Scott’s status, and therefore he should be returned to slavery. However, the announcement is delayed when a conflict arises over the basis for the judgment.

- Some favor “jurisdictional” reasons – the case should never have gone into the Federal court system in the first place. The reason, according to majority opinion, is that Scott is a slave, and slaves are not U.S. citizens.

- Thus he had no right to appear in, or appeal to, a federal court. But since the Sanford defense never made this argument, could it be legally cited as the reason to remand the case to the Missouri Supreme Court?

- Other justices oppose sending the case back on a technicality, rather than using it to once and for all take a stand on all of the Constitutional issues around slavery that have been tearing the union apart.

There is also a political component to the delay. Chief Justice Taney fears that with the 1856 presidential election coming in less than a year, a decision to deny Scott his freedom will look to the public like another “Slave Power” outcome, with the five southern justices ramming it through. Thus the justices agree to re-hear the case after a new President has been chosen.

This second hearing occurs December 15-18, 1856, and within chambers it again appears that the court will defer for jurisdictional reasons to the Missouri ruling against Scott, thus dodging the more profound “substantive” issues.

But then two of the northern justices rock the boat. They are the venerable, and politically well connected, John McLean of Ohio, and the only Whig on the court, Ben Curtis of Massachusetts. Both say they intend to draft strong “dissents” on the basis of the case law precedent, “once free, forever free.” They are particularly convinced here by the fact that Dr. Emerson actually left the Scotts in a free state at Ft. Snelling when he went back to St. Louis.

At this point an extraordinary, and highly controversial intervention occurs. It involves none other than President-elect James Buchanan who sends a note to his friend, Justice John Catron of Tennessee, asking about the status of the case. Catron replies that a decision was possible soon, but that a third northern judge, Robert Grier, might join McLean and Curtis in dissenting. Catron asks Buchanan to “drop Grier a line,” to see what he is thinking.

The President follows through with Grier, a fellow Pennsylvanian, and graduate of Dickinson College. Grier tells him that he wants a “broad decision,” not simply based on technicalities, and is working toward this with the other justices. And so the critical Constitutional issues around slavery are finally confronted in the justice’s chambers:

- Can a negro, slave or free, become a citizen of the United States?

- Does a negro have any “standing” or “rights” within the judicial system?

- Can a slave be set free by anyone other than his owner?

- Can a state refuse to allow an owner to bring a slave into their territory?

- If an owner takes a slave into a “free state,” is the slave automatically freed?

- Is the Missouri principle – “once free, always free” – constitutional?

- Is the Missouri Compromise, banning slavery where Scott lived, constitutional?

- Is the notion of “popular sovereignty” even legal?

- In the end, is a negro anything more than a piece of property under the law?

Since 1787, the American political system has darted and dodged its way around direct answers to these questions.

Now the Supreme Court, led by Taney, decides to plunge all the way into them, with the President and the nation anxiously awaiting their rulings.

March 7, 1856

The Supreme Court Rules Against Dred Scott And Overturns Prior Case Law On Slavery

While Chief Justice Roger Taney will be remembered and maligned for his Dred Scott decision, he is still regarded by most legal scholars as one of the preeminent jurists in American history.

He is a complex man. His roots are firmly in tidewater Maryland, but he is not wealthy, and he shares in the common man tradition of his friend, Andrew Jackson, who names him to succeed John Marshall on the bench in 1836, starting his 28 year career there.

Taney struggles all his life with the slavery issue. He frees his own slaves upon inheriting them. In 1819 he defends a Methodist preacher, who is an abolitionist, with these words:

Slavery is a blot on our national character, and every real lover of freedom confidently hopes that it will effectually, though it must be gradually, be wiped away; and earnestly looks for the means, which this necessary object may best be obtained.

Like Jackson, he is also a loyal Unionist, who will condemn secession, swear in Abraham Lincoln, and serve under him until his death in 1864. But first and foremost, Taney is a letter-of the-law Constitutional lawyer. The founders, like Taney, may have wished for slavery to gradually wither away, but what rules did they actually write down in 1787 to govern it?

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court hands down its ruling in the Dred Scott case, deciding by a 7-2 margin in favor of Sanford and returning the Scotts to slave status.

It is a “broad decision,” as sought by Grier, and Taney relies upon himself to render the majority opinion. He begins by reflecting on how the negro race was viewed in 1787 by the founding fathers:

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in regard to that unfortunate race which prevailed in the civilized world at the time when the Constitution of the United States was adopted; but the public history of every European nation displays in a manner too plain to be mistaken. (Negroes) had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far unfit that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.

Thus, for Taney, the words in the Constitution are “too plain to be mistaken.” They say that negroes are “property,” nothing more and nothing less. From there he announces four main conclusions:

First off, the Supreme Court has no jurisdiction over Scott’s case.

- As a negro, Scott is not, and cannot become, a citizen of the United States.

- Therefore he had no right to appeal the Missouri state decision in Federal court.

Second, the only way that Scott could be freed is if his owner declares him free.

- In 1787 slaves were bought and sold, and became the “property” of their owners.

- “Property rights” are protected under the Fifth Amendment “due process” clause.

- Owners do not forfeit their property simply by moving it to a “free state.”

- Hence the Missouri “once free, always free” principle lacks merit.

Third, the entire 1820 Missouri Compromise Act is unconstitutional.

- It argued that slaves could be banned in the new territory north of the 30’36” line.

- But slaves are “property” and transport of property across state lines is protected.

- Congress over-stepped its powers in trying to limit the free movement of property.

Fourth, granting Scott freedom and the right to sue would lead on to a slippery slope.

- Taney foresees future petitions around freedoms of speech, travel, protest, and arms.

- None of these “rights” were envisioned for negroes by the founding fathers.

- Even debating them now will exacerbate sectional tensions and threaten the union.

Despite the 7-2 overall majority, all nine justices feel compelled to write concurring or dissenting opinions, covering 250 pages and taking up two full days to be read aloud in court. Those who quarrel with Taney’s summary are troubled by three things: voiding the case law associated with “once free, forever free;” the fact that negroes have already been declared citizens in five free states; and the anticipated public chaos that is sure to follow the rejection of the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

September 30, 1857

Justice Benjamin Curtis Resigns Over The Ruling

Two of the four Northern justices – John McLean and Benjamin Curtis – disagree with the verdict, with Curtis writing a very lengthy and detailed rebuttal.

He begins by attacking the one conclusion of the court that is most devastating to the hopes of all free blacks – Taney’s assertion that negroes cannot become citizens of the United States. That’s in error, according to Curtis, and he dismisses it on simple logic:

First, that free citizens of each State are citizens of the United States. Second, that free colored persons born within some States are citizens of those States. (Therefore) such colored persons are also citizens of the United States.

By way of support, Curtis cites the Constitutions of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York.

Persons of color, descended from African slaves, were by their Constitution made citizens of the State and such of them as have had the necessary qualifications have (even) exercised the elective franchise, as citizens, from that time to the present.

For the Supreme Court to now declare that these free blacks were not actually citizens of their State or of the United States would be “received with surprise by the people who know their own political history!”

I dissent, therefore, from that part of the opinion of the majority of the court, in which it is held that a person of African descent cannot be a citizen of the United States.

He then broadens his dissent, arguing that once the court decided that Scott had no standing as a slave, other findings including those on the 1820 Missouri Act should be regarded as obiter dictum, a mere opinion not matters of law.

I regret I must go further, and dissent both from what I deem their assumption of authority to examine the constitutionality of the act of Congress commonly called the Missouri Compromise act, and the grounds and conclusions in their opinion.

Finally, according to Curtis, the facts show that Scott was a free man from the moment Emerson took him to reside in Illinois, then allowed him to marry and remain behind at Ft. Snelling when the doctor was transferred to St. Louis.

In my judgment, there can be no more effectual abandonment of the legal rights of a master over his slave, than by the consent of the master that the slave should enter into a contract of marriage, in a Free State, attended by all the civil rights and obligations which belong to that condition. This consent…is an effectual act of emancipation.

Justice Benjamin Curtis then closes.

In my opinion, the judgment of the Circuit Court should be reversed, and the cause remanded for a new trial.

Six months later, on September 30, 1857, Curtis resigns from the Supreme Court over the ill will surrounding the Scott decision. In so doing he becomes the only court member in history to resign over a matter of principle.

He is 47 years old at the time, and in his six years on the court has established a reputation as one of the brilliant legal minds in the U.S. In later years, he will argue many cases in front of his old court and will defend Andrew Johnson as chief defense counsel in his 1868 impeachment trial.

1857 Forward

The Dred Scott Ruling Drives The Country Closer To Sectional Warfare

While the South regards the court’s decision as a total vindication of its positions on the black race and on slavery, the ultimate result will be a hardening of antagonism toward their section across the North and the West.

The response among Republicans will prove most decisive in this regard.

They argue in a nutshell that the Southern-dominated court has just “nationalized slavery” – forcing it upon those in the North and West who want it to wither away, not expand.

With the stroke of a pen, the minority wishes of the Slave Power have washed away the will of the majority, including the protections afforded by the 1820 Missouri Compromise, and even the right of western settlers to forbid the invasion of blacks from the moment a new territory is formed.

The Republicans argue that, as with prior attempts at “nullification,” the Dred Scott ruling must be ignored in practice and is doomed to fail in the end.

Different factions within the party have very distinct reasons for their opposition. A large segment simply wants to exclude all black expansion on behalf of prerogatives belonging properly to white men. Then there are those who oppose slavery on moral grounds, while remaining skeptical about assimilation and granting of citizenship. Lastly come the much smaller core of radical abolitionists calling for the immediate emancipation of all slaves and genuine equality.

Representative Republicans Opposing The Dred Scott Ruling

| Segments | Some Leaders |

| White supremacists | Wilmot, Banks, Fremont, Lane |

| Conservative anti-slavery | Seward, Lincoln, King, McLean, Cameron, Blair |

| Abolitionists | Giddings, Hale, Stevens, Chase, Sumner, Wilson |

Public outrage across the North and West is fanned by newspaper editorials attacking the ruling, along with Chief Justice Taney and his Slave Power cronies on the court. On March 12, 1857, the Chicago Tribune writes of the “judicial revolution:”

We must confess we are shocked at the violence and servility of the Judicial Revolution caused by the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. We scarcely know how to express our detestation of its inhuman dicta or fathom the wicked consequences which may flow from it . . . . To say or suppose, that a Free People can respect or will obey a decision so fraught with disastrous consequences to the People and their Liberties, is to dream of impossibilities.

The leading abolitionists add fuel to the notion of resisting the decision entirely. In typical fashion, Lloyd Garrison splashes a large type headline across the front page of the Liberator:

THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT IS THE MORAL ASSASSINATION OF A RACE AND CANNOT BE OBEYED

Frederick Douglass joins in with a speech condemning the court on May 14, 1857:

Have no fear that the National Conscience will be put to sleep by such an open, glaring, and scandalous tissue of lies as that decision is, and has been, over and over, shown to be…By all the laws of nature, civilization, and of progress, slavery is a doomed system. Not all the skill of politicians, North and South, not all the sophistries of Judges, not all the fulminations of a corrupt press, not all the hypocritical prayers, or the hypocritical refusals to pray of a hollow-hearted priesthood, not all the devices of sin and Satan, can save the vile thing from extermination

Legal scholars offer another recourse, arguing that once Taney found that Scott had no right to even appear in a federal court, all of his subsequent dictates became obiter dictum – an incidental expression of opinion, not essential to the decision and not establishing precedent. This opens the door to calls across the North to simply ignore the more sweeping aspects of the ruling.

Lincoln will face into these calls during his famous upcoming debates with Stephen Douglas. He will point out that the decision was made by a “divided court dividing differently on the different points.” Also that, while he disagrees with it and intends to pursue it as a “political matter,” disobedience must not be condoned.

March 1857

The Decision Also Calls “Popular Sovereignty” Into Question

The high court’s ruling clearly says that blacks cannot sue in federal courts and that Congress cannot forbid slave owners from taking their “property” wherever they want. In effect this overturns the “once free, forever free” case law precedents. Owners need no longer fear that their slaves will be appropriated anytime they take them into the historically Free States.

The question then becomes what Dred Scott means in regard to expanding slavery into the new western territories. Declaring the 1820 Missouri Compromise “unconstitutional” changes little, since the Kansas-Nebraska Bill already wiped away the 36’30” demarcation principle. So was the high court actually saying that slavery must be declared legal and supported from Kansas to the west coast?

The South, of course, wants to read the ruling that way – as a total victory, ending all opposition to their “right” to open new plantations wherever they desire, starting in “bloody Kansas.”

But for the Democratic Party, this interpretation would appear to negate their call for “popular sovereignty” to settle the slavery issue. “Let the people decide” has been their political battle cry since 1848, when Lewis Cass and Stephen Douglas first arrived at it. And, as of 1858, the popsov plank is the major public policy difference between them and their Republican rivals – who would ban all slavery in the west based on what they regard as the original intent of the founding fathers (“let it wither away”).

No two Democrats have been more visibly associated with popsov than President Buchanan and Stephen Douglas.

True to his reputation as a “doughface,” Buchanan is delighted by the court’s ruling. He also believes, naively, that it will finally end the controversy over slavery that has plagued his entire time in office.

On the other hand, Douglas views the outcome as threatening to make his popsov campaign look irrelevant and, in turn, to cause a major sectional schism among the Democrats. From this point forward, his relationship with Buchanan deteriorates from political rivalry to outright distrust and animosity. The public split will come to a head nine months hence, over the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution in Kansas.

Unlike Buchanan, Douglas is also facing an election campaign in the Fall for his senate seat from Illinois. This has raised his awareness of Northern resistance to the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, and he anticipates an even sharper outcry against Dred Scott. Have the Democrats simply become the instrument of the Slave Power to spread more unwanted negroes at the expense of white men? Douglas also senses the rise of his old Springfield foe, Abraham Lincoln, and tells friends that he will be a formidable opponent.

All of this forces Douglas to try to square the Dred Scott ruling with his own popsov convictions. He eventually does so arguing that, while the law says that slavery cannot be banned in the new territories, in practice it cannot survive without local police enforcement, which rests on the will of the people. QED, a final vote by the people is as critical as it ever was.

This will be his justification for popsov when time comes to debate Lincoln.

Sidebar: The Fate Of Dred Scott

By 1857, Dred Scott has been transformed into a symbol of the debate over the future of slavery in America that will soon lead to the Civil War.

But behind the symbol are a flesh and blood man, his wife, and two children who have lived in limbo between slavery and freedom for two full decades, spurred by Dr. Emerson’s transfer to the state of Illinois.

When the Supreme Court rules that the Scotts are nothing more than ‘property,” Dred is an aging man of sixty-one still needing to make his way in the world that has little sympathy for his race.

But fortunately, some are on his side, most notably descendants within the Blow family, his original owners. After the trial they convince Mrs. Emerson to finally hand them over, and when this happens, the Blows set them all free, at last. But Dred’s time as a free black is brief. After returning to St. Louis, where he becomes a porter in a hotel, tuberculosis takes him on September 17, 1858. He is buried in the Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, with a tombstone reading: “In memory of a simple man who wanted to be free.” To the present day, visitors are wont to place Lincoln pennies, heads-up, at the plot.