Section #21 - A North-South Split in the Democrat Party leads to a Republican Party victory in 1860

Chapter 253: The Reconvening Democrats Nominate Two Separate Tickets

June 11, 1860

Dissenters From The First Democratic Convention Meet To Plot Strategy

Seven weeks pass between the collapse of the Democratic Convention at Charleston and the party’s follow-up effort scheduled to open June 18, 1860, in Baltimore.

The interim is spent searching for any form of compromise between the largely Northern faction backing Stephen Douglas and popular sovereignty, and delegates from the seven Southern states who bolted after their platform demand for a Congressional bill protecting slavery was defeated.

On June 11, before the second convention, an informal meeting is held in Richmond to settle on a unified strategy among the bolter states: Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, Mississippi, Florida, Texas, and Delaware.

The debate is between those who would immediately form a separate party to protect the interests of the slave states and those who wish to retain their long-standing identity as Democrats.

The separatists involved are well known by this time, especially William Yancey of Alabama and John Slidell of Louisiana. Their message to the potential delegates is well summed up in an editorial written by R.B. Rhett, Jr. in the Charleston Mercury:

The Democratic Party, as a party based on principles, is dead. It exists now only as a powerful faction. It has not one single principle common to its members North and South.

But others at the meeting hear the voice of men like Georgia’s Alexander Stephens, who urges a more cautionary wait and see stance, and this is what prevails. Rather than staying away, the delegates will head to Baltimore and measure the reception they get – one litmus test being whether or not the delegate credentials they carried in Charleston are honored again in Baltimore.

June 18, 1860

The Second Democratic Convention Opens With A Fight Over Seating Credentials

The official Democratic convention opens on June 18 at the Front Street Theater in Baltimore, a two story brick structure sporting a stage and balcony, built-in 1829 to house cultural performances.

While Caleb Cushing, the “doughface” politician from Massachusetts, continues to serve as President, supporters of Stephen Douglas are firmly in charge of the event. His headquarters are set up at the nearby home of Reverdy Johnson, the prominent Maryland Democrat, and his floor manager is again William Richardson of Illinois, a long-time partner in driving legislation through Congress. The Little Giant is confident of a victory:

All we have to do is to stand by the delegates appointed by the people in the seceding states in place of the disunionists.

The atmosphere, however, is tense by the time the first session is called to order at 10am. Even the benediction, spoken by the Reverend John Macron, is a plea for restraint amidst the “rising tempest of sectional discord.”

As the waters of the political deep are agitated by the rising tempest of sectional discord, give the spirit of a large and liberal forbearance to everyone that “peace may be within our walls and prosperity within our palaces.

The immediate source of stress is a battle over seating credentials that soon focuses on delegates from Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia in particular. This pairs attendees who had walked out in Charleston against “new slates” recently chosen in state conventions that favor Douglas.

For three solid days the Credentials Committee searches for an accommodation that satisfies both sides.

As this drags on, Douglas sends a rather astonishing letter to Richardson, offering to withdraw his name if those present think it will restore party unity:

I learn there is eminent danger that the Democratic Party will be demoralized if not destroyed by the breaking up of the convention…If therefore you and any other friends…shall be of the opinion that…the Democratic Party (could be) maintained, and the country saved from the perils of Northern abolitionism and Southern disunion by withdrawing my name…I beseech you to pursue that course.

Richardson pockets the letter, although inquiries go to the New York delegation to see if they have an option to Douglas who might restore order. The Georgia Unionist, Alexander Stephens, is mentioned, but even he is considered too soft on guaranteeing slaveholder rights for Yancey, Slidell and other fire-eaters.

On June 21, the fourth day of the convention, the Credentials Committee issues its majority report calling for:

- Re-admitting original delegates from Texas and Mississippi plus some from Arkansas and Delaware;

- Declining those from Alabama and Louisiana in favor of newly elected (Douglas) alternates; and

- Accepting and equal mix of old and new delegates from Georgia, with each given 0.5 votes.

This motion passes by a 150.5-100 margin on June 22, but with a proviso from New York, allowing for members to consider a possible response from those who have been excluded.

June 23, 1860

Douglas Wins The Nomination After Fifteen States Exit The Convention

Rejection of the original Charleston delegates sparks a Southern states walk-out that signals the death knell for the Democratic Party coalition that will persist for the next twenty-five years.

Within hours, the initial nine “bolters” are joined by attendees from Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Maryland, along with those from California and Oregon. They will be joined by Kentucky the following day.

Of the original 303 delegates to be seated, a total of roughly 108 leave the hall.

What follows is a mad dash to complete the nominating process and close the event.

Despite the obvious fact that Douglas will win, six other names are offered up almost out of spite. What follows is another humiliation after he tallies 173.5 votes on the first ballot only to encounter the “convention rule” requiring the winner to get 2/3rds of the original delegate count (i.e. 202) – now a mathematical impossibility.

A motion to re-set the standard at 2/3rds of the votes cast leads to a victory for Douglas on the second roll call.

Presidential Nomination Results

| Candidates | State | 1st | 2nd |

| Stephen Douglas | IL | 173.5 | 181.5 |

| James Guthrie | Ky | 9 | 5.5 |

| John Breckinridge | Ky | 5 | 7.5 |

| Horatio Seymour | NY | 1 | 0 |

| Thomas Bocock | Va | 1 | 0 |

| Daniel Dickinson | NY | 0.5 | 0 |

| Henry Wise | Va | 0.5 | 0 |

| Total | 190.5 | 194.5 | |

| Needed To Win | 202 | 130 |

Dysfunction continues with the selection of a running mate. Douglas signals his interest in Alexander Stephens, but his managers insist that any remaining hope for unity rests with allowing the remaining Southern delegates to select their favorite. Their fury toward William Yancey of Alabama leads them to choose Benjamin Fitzpatrick, the 57 year old ex-Governor of the state, and now one of its sitting U.S. Senators.

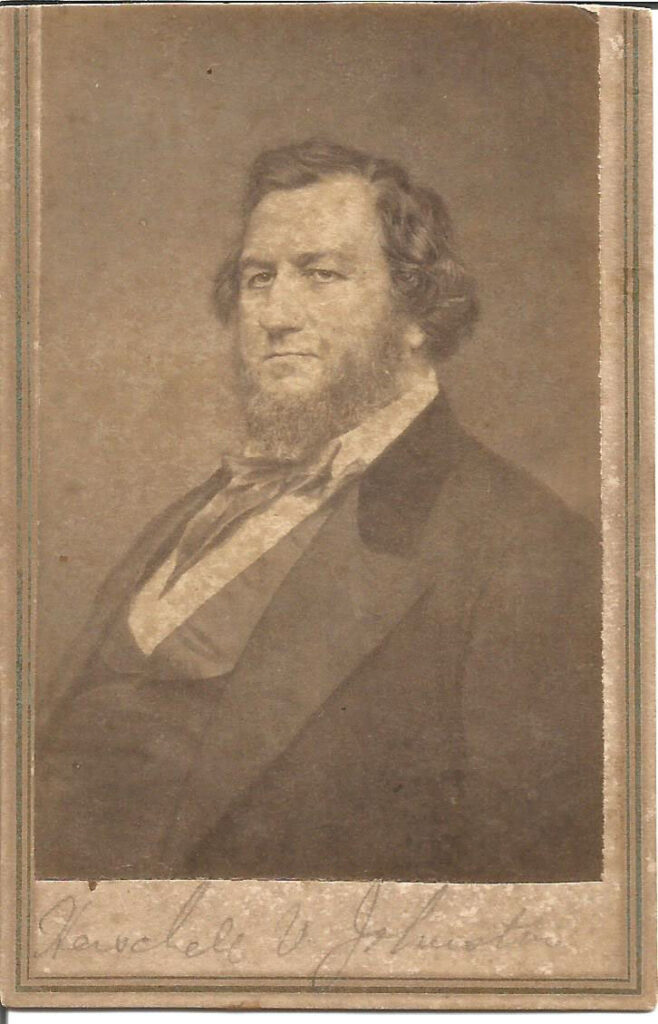

But Fitzpatrick neither supports Douglas’ commitment to popular sovereignty nor wants to risk his own public support in Alabama, and he quickly turns down the nomination. He is replaced by Herschel V. Johnson, a planter and slave-holder, who has formerly served as Governor and Senator from Georgia. While Johnson will eventually serve in the CSA Senate, in 1860 he is still hoping to avoid secession.

The closing business at Baltimore involves platform support for Douglas’ fall-back position trying to square his popular sovereignty with the Dred Scott – namely that the final say on slavery in the new Territories will rest with the U.S. Supreme Court.

A twenty-five man National Committee is also named to oversee the upcoming campaign. It is headed by August Belmont, born in Germany and educated in Jewish schools, before coming to New York in 1837 to support the Rothschild Company during the financial panic that year. Belmont proves his worth throughout the race and continues to serve as Chairman of the Party for the next twelve years. He will also be remembered for his horse racing passion, as founder of The Belmont Stakes.

On the evening of June 23, a somber Stephen Douglas meets with supporters at a railway station in Washington, telling them that:

Secession from the Democratic Party means secession from the federal Union.

Events will prove him right on that assessment.

June 23, 1860

The Break-away Southern Democrats Nominate John Breckinridge

Unlike the “wait and see” tactic they followed back in Charleston, the “Bolter” states decide that a permanent split with the Northern Democrats is now unavoidable.

On the same day that Douglas is nominated, they re-group at the Maryland Institute Hall to pick their own ticket and settle on their demands regarding slavery. They number over 100 delegates, coming from the 15 slave states plus Oregon, California and a few members from New York and Massachusetts. The latter includes Caleb Cushing who shifts from presiding over the original convention to do the same for the Southerners.

By in large the majority remain opposed at this point to leaving the federal Union. But they know that their future economic well being rests on extending slavery to the west, and their platform remains unchanged from the minority report which was voted down at Charleston.

It calls upon Congress to pass a law protecting the rights of slave-owners and their “property” in the territories.

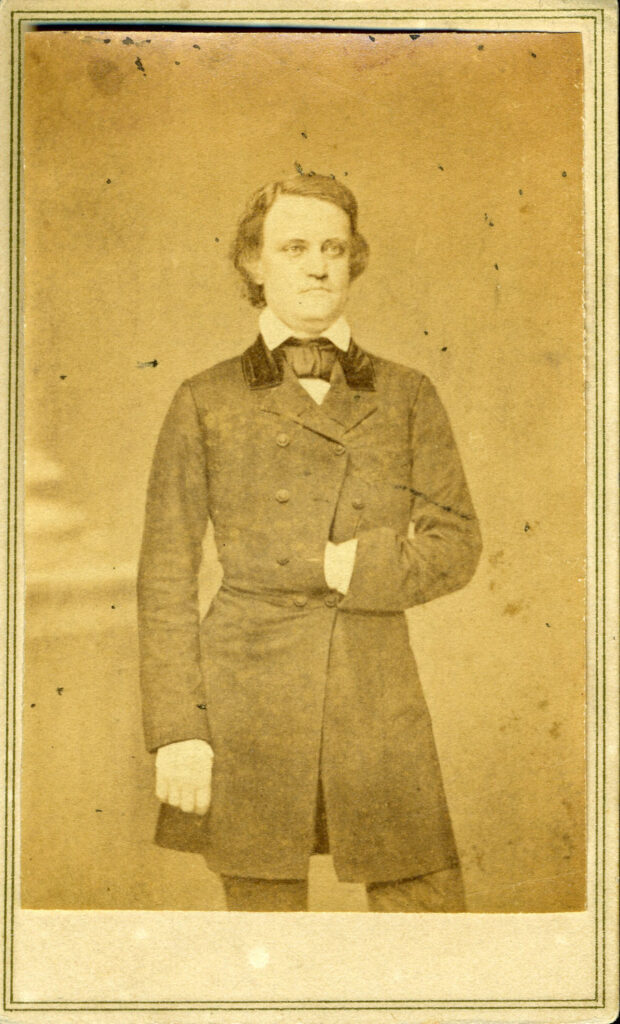

Two candidates are nominated for President: America’s current Vice-President, John Breckinridge, from Kentucky, and Daniel Dickinson, the ex-Senator from New York. Both men are letter-of-the-law Constitutional conservatives.

Breckinridge prevails on the first ballot.

Nomination Results: Southern Democrats

| Candidates | State | 1st |

| John Breckinridge | Ky | 81 |

| Daniel Dickinson | NY | 24 |

| Total | 105 | |

| Needed To Win | 70 |

Joseph Lane, the pro-slavery Senator from Oregon, is chosen as Vice-President.

The convention is about to end when the Alabama fire-eater, William Yancey, grabs the floor and delivers what is generally seen as an “unhelpful tirade” on behalf of secession.

Still the drama continues after the session ends.

When Breckinridge learns of his nomination, he says that he intends to reject it, on the grounds that it will only guarantee the election to Abraham Lincoln. This holds until he meets with Jefferson Davis, who posits the only way out for the South. That would be an agreement between Lincoln’s three opponents – Breckinridge, Douglas and John Bell – to all withdraw their names, and unify behind a single anti-Republican candidate, to be chosen later.

Davis argues that this single opponent should be able to either defeat Lincoln outright or, at least, deny him the needed majority in the Electoral College, and throw the election back into the House. Once there, the South would indeed have a chance, given that each state would be given one vote to cast and a simple majority would be needed to win.

Even though the existing split in the House is 15 Slave States versus 18 Free States, several states (e.g. California, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and even New York) just might reject Lincoln, giving his opponent a chance at victory.

But Stephen Douglas refuses to go along, believing that many of his voters would simply switch to Lincoln over either a Southern slave owner (e.g. Stephens) or another Northern doughface like Buchanan (e.g. Dickinson or even Cushing).

With the “all drop-out” notion gone, Breckinridge finally agrees to stay in and represent his region.

Sidebar: The Politician Warrior John Breckinridge

John Breckinridge is a loyal defender of slavery, but by no means a member of the Fire-eater class of Southerners who lobby for years on behalf of secession.

He models himself after two moderate political giants from Kentucky, the Whig, Henry Clay, and the Democrat, John J. Crittenden. His friendships extend in many directions, including Abraham Lincoln and his distant cousin, Mary Todd Lincoln.

He becomes Vice-President of the United States at 35 years old, after passing the bar in 1841, entering politics to campaign for James Polk in 1844, and serving as Major of the 3rd Kentucky Regiment, which arrives in Mexico City after the combat has ended. It is said that his eulogy on behalf of Henry Clay, Jr., killed at Buena Vista in February 1847, brings tears to the father’s eyes.

Breckinridge is forever cautious about “waiting his turn” when it comes to politics, but he finally runs, and is elected to the US House in 1851 and again in 1853 as a Democrat. When Clay himself dies in 1852, he delivers another moving memorial in Congress. During that year, he stumps for Franklin Pierce, who twice offers him government positions he turns down, first as Governor of the Washington Territory and later as Minister to Spain.

Given his subsequent break with Stephen Douglas, it is ironic that he supports his 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act and the principle of popular sovereignty, and almost fights a duel over it with one Francis Cutting, a fellow Democrat in the House.

The sharp rise of the Know-Nothing Party in Kentucky convinces Breckinridge to forego the race for a third term, and he returns to his Lexington law practice, along with promoting horse racing and breeding in the state. Soon enough, however, the 1856 events in “bloody Kansas” bring him back into the political arena and force him to take a more assertive stance on slavery.

While he owns a handful of slaves between 1849 and 1857, the Presbyterian church he attends condemns the practice, he defends “free blacks” in court, and supports “colonization.” But he is also a Southerner and a lawyer who is convinced that the 1787 Constitution guarantees slave holders the absolute right to take “their property” into the new Territories at least until statehood. Again ironically, Breckinridge backs first Pierce and then Douglas, still a friend, for the 1856 nomination. Buchanan will never forgive him for this, but does agree to have him join the ticket as Vice-President, to help carry the South – including Kentucky, which the Democrats win for the first time since 1828.

His final split with Douglas occurs when the Illinois Senator refuses to support the admission of Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution. Breckinridge, like Clay and Crittenden, is committed to the sacred Union, and fears that Douglas’s action will fatally divide the Democratic Party and the nation.

With the sectional chaos mounting, his Vice-Presidential duty of presiding over the Senate is completed “respectfully and impartially.” Fellow Kentuckians look to him next to fill a Senate seat of his own, after Crittenden retires, and he is nominated for that slot in late 1859. His acceptance speech on December 12, 1859 praises the Dred Scott ruling and attacks John Brown’s raid, but still opposes all talk of secession.

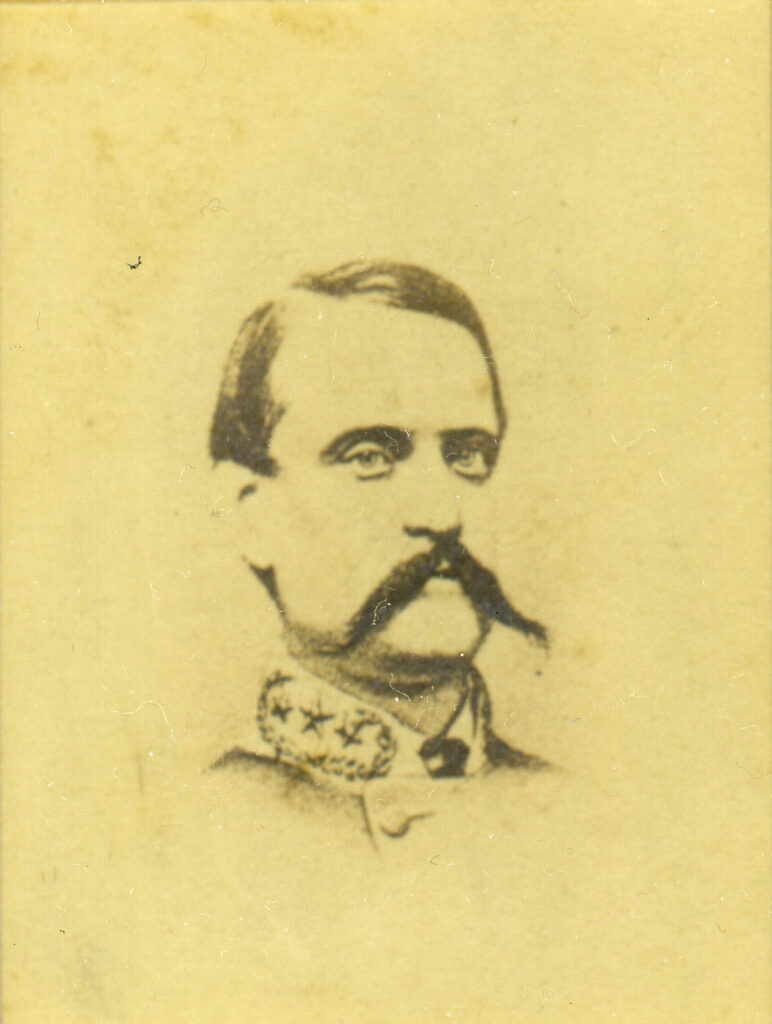

He deflects moves to nominate him for president at the Charleston Convention in May, but then agrees to run after the Democratic schism at Baltimore in June. In the fall he will win 18% of the popular vote and 72 Electoral votes, second only to Lincoln. Despite the loss, he greets Lincoln and Mary to DC and helps create the “Committee of Thirteen,” which fails to stop secession. On April 2, 1861 he pleads for peaceful reconciliation before the Kentucky General Assembly; ten days later the guns at Ft. Sumter issue in the Civil War.

Breckinridge now must choose between the Union and the Confederacy and he goes with the South, being appointed Brigadier General of the 1st Kentucky Regiment on November 2. Two of his sons enlist with him and two others fight for the USA. On December 4, 1860 he is expelled from the Senate seat he just won, declaring:

I exchange with proud satisfaction a term of six years in the Senate…for the musket of a soldier.

Thus begins a remarkable record as a Confederate army field commander. He leads his “Orphan Brigade” at Shiloh in April 1861, where he receives his first wound and is promoted to Major General. In early January 1863 he fights heroically at Stones River. He falls out with Braxton Bragg after summer 1863 battles at Vicksburg and Chickamauga, and goes east to join Lee’s troops, winning further fame at New Market in May 1864, being wounded again at Cold Harbor in June and being declared the “second Stonewall” for his dying days victories in the Shenandoah Valley. On January 19, 1865, Jefferson Davis names him Secretary of War, and his first act is to name Lee as General-in-Chief. By then, however, the cause is lost, and he urges Davis to end it.

This has been a magnificent epic. In God’s name let it not terminate in farce.

Ten days after Lee surrenders on April 9, Lincoln is assassinated and Breckinridge mourns the loss: “Gentlemen, the South has lost its best friend.” In turn he flees to Cuba on June 11, then to Britain, and back to Toronto in September 1865. On Christmas day 1868, President Johnson pardons all Confederates, and Breckinridge is back home in Lexington in March 1869, where he resumes his law practice. On March 17, 1875, he dies after surgery on his liver, damaged during the war – having packed an amazing life into only 54 years!

Summer 1860

The Nominating Conventions Are Now At An End

Once the Southern “Bolters” settle on Breckinridge and Lane, four distinct tickets have been identified, and the search for a solution to the issue of slavery in the west is in the hands of the voting public.

Recap Of The Nominating Conventions In 1860

| Party | Date | City | Ticket |

| Democrats | April 23-May 2 | Charleston, SC | None |

| Constitutional Union | May 9 | Baltimore, MD | John Bell & Edward Everett |

| Republican | May 16-18 | Chicago, IL | Abraham Lincoln & Hannibal Hamlin |

| Southern “Bolters” | June 11 | Richmond, Va | None |

| Democrats | June 18-23 | Baltimore | Stephen Douglas & Hershel Johnson |

| Southern “Bolters” | June 23 | Baltimore | John Breckinridge & Joseph Lane |