Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

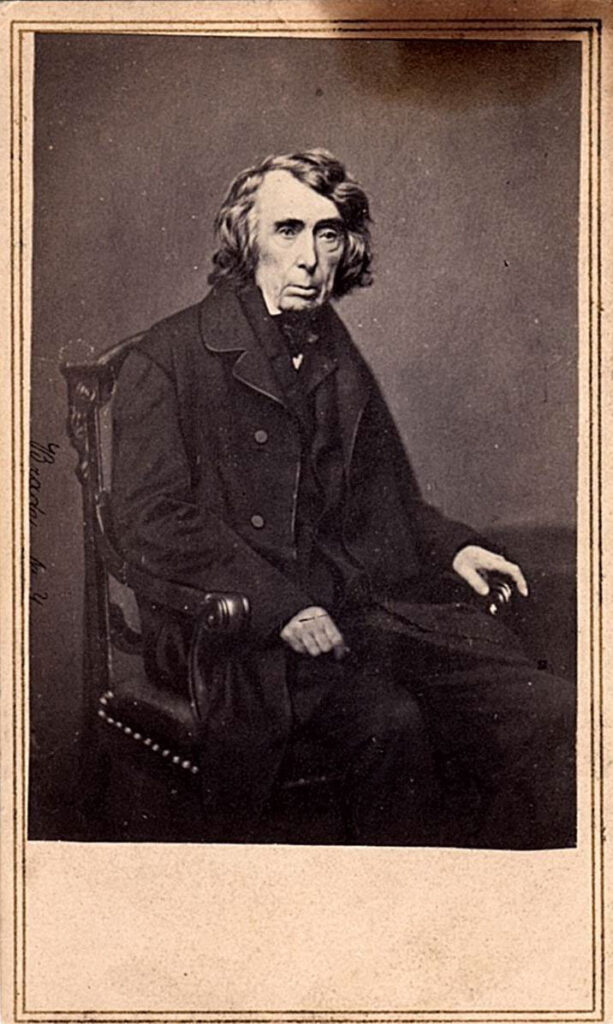

Chapter 77: Roger Taney Becomes Chief Justice Of The Supreme Court

March 15, 1836

John Marshall Dies And Jackson Names Taney As His Successor

Jackson’s second term includes one other legacy that will affect the course of history over the next 28 years – his selection of Roger B. Taney as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Taney replaces the former Chief, John C. Marshall, who serves for 34 years and essentially establishes the Court’s status as a co-equal branch of the federal government.

Marshall also proves to be a thorn in the side of Anti Federalists, like his cousin, Thomas Jefferson, and others who follow in the Democratic-Republican Party. He does so by consistently affirming the supremacy of federal laws over state laws, and by extending the scope of cases and issues brought before the Court.

Marshall dies on July 6, 1835, and Jackson turns to his longtime friend and to fill the vacancy.

Roger Taney (pronounced Tawney) is born in 1777, the second son of a wealthy tobacco planter in Maryland. He is a frail youth, devoted to his Catholic faith and to his studies. Since his older brother Michael is destined to inherit, his father enrolls him at Dickinson College at fifteen, and he graduates from there in 1796.

After further training in the law, he passes the bar in 1799 and opens his own practice in the town of Frederick. His family reputation opens the door for him to politics, and he is elected to the Maryland House of Delegates. He is a staunch Federalist until his support for the War of 1812 accompanies a conversion to the Democrat-Republican camp.

In 1819, at age forty-two, his personal circumstances change when Michael Taney stabs a neighbor to death in a fight and then, to protect the family inheritance, transfers 800 acres of land and thirteen slaves to Roger and another sibling. A year later, upon the death of his father, he frees all of his slaves, and expresses his personal view on the institution:

Slavery is a blot on our national character, and every real lover of freedom confidently hopes that it will be effectually, though it must be gradually, wiped away.

Soon thereafter, Taney becomes an avid supporter of Andrew Jackson and campaigns for him in the “stolen election” of 1824. He then serves as Attorney General of Maryland from 1827 to 1831.

His move into national politics comes suddenly in 1831 when now President Jackson overhauls his entire cabinet in response to the “petticoat affair,” and names Taney his Acting Secretary of War, a position he holds for ten months. He then serves as U.S. Attorney General before Jackson nominates him in 1833 to become Acting Treasury Secretary, where he seals the fate of the Second U.S. bank. Then Jackson nominates him for the high court.

The move is met with resistance by those who oppose Jackson at every turn. In January 1835, Clay’s Whig supporters deny Taney’s nomination to serve as an Associate Justice on the Court.

When the President sends his nomination up again on December 28, 1835, it is again met by stiff opposition from Clay, Calhoun and Webster. But even that potent combination cannot prevail over a Senate full of Jackson men, and Taney is finally confirmed on March 15, 1836.

Taney will go on to become the second longest Chief Justice in history, serving for a total of twenty-eight years. His record will place him alongside Marshall and Joseph Story as one of the three greatest Justices on the high court. All this despite the criticism registered on the Dred Scott ruling in 1857.

February 14, 1837

Community Interests Prevail In Charles River Bridge v Warren Bridge

As a justice, Taney is a strict “letter of the law” adherent to the Constitution, and, like Jackson, favors state’s rights over federal intrusion.

While he only serves one year during Jackson’s final term, one ruling stands out in particular – that being Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge.

Here the state of Massachusetts has contracted with the Charles River Bridge Company (CRBC) in 1785 to build a 1503 feet span connecting Boston to Charleston and saving travelers from an 8 miles roundabout trek. In payment for the bridge, the Company is granted rights to collect user tolls for a 70-year period, at which time the bridge would become state property.

The bridge proves to be an overnight success, and the original owners eventually reap huge profits by selling their shares to later investors. As the population of Boston grows so too do the profits to the company and the complaints of the public about the toll rates being charged. When the new owners refuse to adjust the charges, the state decides to build what will become the nearby Warren Bridge, to be free to travelers after an estimated six-year toll period to pay off the construction costs.

Owners of the Charles River Bridge Company see that this “free” Warren Bridge will end their ability to charge a toll and, hence, their source of profits — and view this as a violation by the state of their 70-year contract. They respond with a lawsuit asking the court to prohibit construction of Warren Bridge.

The case eventually reaches the U.S. Supreme Court in 1831, and it appears that John Marshall and his “pro-business” colleagues are about to side with the company over the state. But administrative matters delay the ruling, and then turnover in the justices, culminating in Marshall’s passing, forces the case to be reargued in 1837, with Taney now presiding.

In the interim, the Warren Bridge has actually been built, has achieved a free/no toll status, and has indeed dried up traffic across the Charles River Bridge.

Despite this outcome, the Taney court votes 5-2 in favor of the state over the CRBC plaintiff.

Taney concludes that the original contract did not overtly grant “exclusivity” to CRBC and that the new Warren Bridge is simply an example of the state doing its job by acting in the best interest of its citizens.

While the rights of private property are sacredly guarded, we must not forget that the community also have rights, and that the happiness and well-being of every citizen depends on their faithful preservation

In regard to the company’s lost toll profits, he argues that such outcomes are built into the evolving nature of commerce – canals cut into toll road profits and perhaps the new trains will impact canals in the same fashion. One cannot prioritize company profits over public progress.

Finally, Taney decides that the will of the Massachusetts’s state legislature should trump any federal issues related to Article I, Section 10 – “no state shall pass any…ex-post facto law impairing the obligation of contracts.”

A vigorous dissent from Taney is registered by veteran justice Joseph Story. He cites the risks taken by the CRBC investors in building what in 1785 was…

The very first bridge ever constructed, in New England, over navigable tide- waters so near the sea one that many believed would scarcely stand a single severe winter.

And he warns that if the rewards of risking capital are threatened by the state, improving public lives will suffer in return. Massachusetts had a good faith contract with the CRBC and ex-post facto they reneged on it.

I stand upon the old law…and can conceive of no surer plan to arrest all public improvements, founded on private capital and enterprise, than to make the outlay of that capital uncertain and questionable, both as to security and as to productiveness

In 1857 Chief Justice Taney will be involved in another case, Dred Scott v Sanford, that will involve protection of another form of “property” – slaves. His decisions here will again prove controversial.

1801-1835

Sidebar: Legacy Of The Marshall Court

Some of the Major Decisions Set Down By The Marshall Court

| Year | Case | Impact |

| 1803 | Marbury v Madison | Judicial review of Congressional laws |

| 1807 | Ex Parte Bollman | Supreme Court power to issue writs/commands to circuit courts |

| 1810 | Fletcher v Peck | First overturn of state law, protects property rights contract |

| 1819 | McCulloch v Maryland | Implied power of Congress to make necessary & proper laws |

| 1819 | Dartmouth v Woodward | Private corporations protected from state interference |

| 1823 | Johnson v M’Intosh | Inability of Native tribes to own lands |

| 1823 | Propagation Of Faith v Town of Pawlet Vt. | Corporations are a “group of individuals in perpetuity,” with protected rights as such |

| 1824 | Gibbons v Ogden | Ends state power to regulate interstate commerce |

| 1825 | The Antelope | Confirms that slaves on board of a ship are legitimate property |

| 1831 | Cherokee Nation v Georgia | Indian nations as foreign states |

| 1832 | Worcester v Georgia | Sanctioning Indian removal |

| 1833 | Barron v Baltimore | Bill of Rights cases limited to federal, not state, challenges |

| 1834 | Wheaton v Peters | Copyright perpetuity |