Section #13 - The 1850 Compromise has Democrats backing “popular sovereignty” voting instead of a ban

Chapter 154: A Filibustering Adventure To Conquer Cuba Is Foiled

1846 Forward

Secessionists Imagine A New Slave Empire To The South

The canal builders are not alone in their territorial interests to the South.

Once it becomes clear that Congress might pass a Wilmot Proviso ban on slavery in the Mexican Cession land, Southern Fire-eaters turn their gaze toward Central America and the Caribbean Islands as potential havens for future expansion.

One among them is John Quitman who envisions a vast Slave Empire extending from Mexico to Central America and across the Gulf to the West Indies.

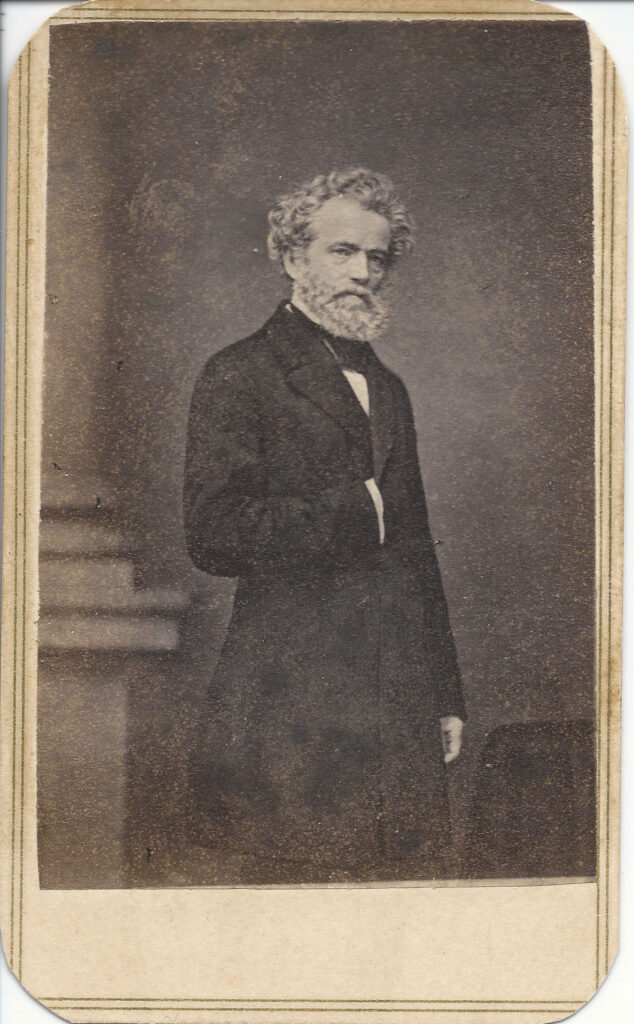

Quitman is a New Yorker by birth who migrates in 1821 to Natchez, a Mississippi River town that is briefly the state’s capitol, as well as jumping off point for the “Natchez Trace,” a prehistoric pathway leading 440 miles east to Nashville. Once there, his legal practices flourishes, he joins the militia, enters state politics, and purchases Monmouth Plantation, in sight of one of the nation’s largest slave trading hubs.

When the Mexican War breaks out, Quitman earns national fame as Brigadier General serving under both Taylor and Scott and accepting the surrender of Chapultepec Castle. He is briefly the Military Governor of Mexico City and argues in favor of annexing the entire country.

After that, Quitman returns to Mississippi, where he builds his reputation as a Southern “Fire Eater” and wins the 1850 election for state Governor. This puts him on the national stage during the conflict over the California admission and Clay’s Omnibus Bill.

He is ready from the beginning to support secession and then create his Slave Empire.

To do so will require a series of filibustering expeditions, similar to those led by Aaron Burr in 1805 and Sam Houston in 1836. As Quitman sees it, these will be led by “America conquistadors” drawn from the ranks of Mexican War military professionals under his command.

One such adventurer is Narciso Lopez who, along with Quitman, sets his sights on Cuba.

1820 Forward

America Has Long Sought To Acquire Cuba

America’s wish to acquire Cuba traces back for decades.

Thomas Jefferson signals his interest in 1820, and John Quincy Adams approaches Spain’s ambassador about an acquisition off and on during his eight year tenure as Secretary of State, under Monroe.

In 1848, President Polk authorizes U.S. Ambassador Romulus Saunders to begin purchase negotiations for “up to $100 million” – but Spain refuses to part with its lucrative sugarcane and coffee operations.

At this point, Narciso Lopez enters the picture with a proposal to Polk for taking Cuba by force.

Lopez is fifty years old at the time, with a prior record of having fought with Spain against Simon Bolivar’s crusade to liberate Latin America, and then, in 1843, alongside the Cubans in their early battles to escape the Spanish yoke.

Lopez flees to America in 1848 after his “Cuban Rose Mine” conspiracy is thwarted.

Once there he continues to seek support for his invasion plan. Polk has already turned him down, and Zachary Taylor follows suit in August 1849. He then shifts his attention to Southern military men but is also rebuffed by Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee before Governor Quitman encourages him to proceed.

1850 – 1851

Narciso Lopez’s Filibustering Campaigns Are Foiled

In May 1850, he assembles some 600 men – mostly veterans of the Mexican War – in New Orleans, and sets sail for Cuba. His force lands on the north coast at Cardenas, some 90 miles east of Havana. He captures the town, but finds little local support there and decides to turn back upon hearing that a large force of Spanish troops is approaching.

Upon his return to America, it is Quitman who pays the price for the invasion – being arrested for violating the 1817 Neutrality Act.

He is forced to resign his Mississippi governorship in February 1851, before being acquitted in three separate criminal trials that all end with hung juries.

Sidebar: Lopez Is Eventually Garrotted To Death

Lopez is undeterred by his 1850 failure, and fifteen months later, in August 1851, he returns with a smaller force of 400 men and lands on the far western edge of the island, at Pinar del Rio.

After being unable again to rally the locals, he is captured this time by the Spanish. On September 1, 1851, he is strapped into a chair and garroted to death at the public square in Havana.

Fifty other Americans are shot at the same time, including “Colonel” William Crittenden, nephew of the then Attorney General, John J. Crittenden.

It remains uncertain whether Lopez intended to rule Cuba in his own name or have it annexed into the United States – but, either way, the tradition of slavery would remain in place.

The failure of the filibustering expedition of 1851 does not put an end to the wish among Southerners to wrest control over Cuba from Spain. It surfaces again in 1854 in the “Ostend Manifesto” prepared by members of the Pierce

administration, which calls for the use of force, if need be, to occupy the island. When made public, however, the Manifesto is roundly opposed in the North, thus ending talk of aggressive action.

Still Cuba remains a critical trading partner with America in the decades ahead. By 1894, some 90% of Cuba’s exports go the United States, with only 6% shipped to Spain. In that same year, the journalist and poet, Jose Marti, initiates a revolution to drive out the Spaniards. America enters the war in May of 1898, landing at Guantanamo Bay. Spain soon surrenders and the December Treaty of Paris finally secures Cuban independence. In 1903 Cuba agrees to lease the naval base at Guantanamo Bay to the U.S. in perpetuity for an annual payment of $2,000. Over a century later that arrangement remains in place.