Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 23: Toussaint’s Slave Rebellion In Haiti Ends With Blacks In Power

1791- 1801

Toussaint Louverture Overthrows French Rule

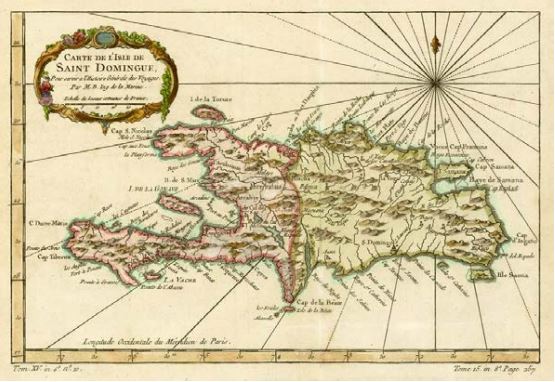

Hiapaniola Island, with the Western Third Saint-Dominigue (Later Haiti)

Thomas Jefferson’s dealings with Napoleon will be shaped in part by the results of a slave rebellion that takes place in the French Colony of Saint-Domingue, or Haiti.

Starting in August 1791 a remarkable revolution is carried out there by black slaves under the leadership of one Toussaint Louverture.

The rise of Saint-Domingue as an important possession for France follows many years of disappointment with its explorations in the Americas.

The Jesuit priest, Jacques Marquette, and the fur trader, Louis Joliet, have opened up outposts along the Mississippi in the 1670-80’s, but these fail to return the gold and silver once sought. By 1762 the French are so dismayed by their economic prospects in North America that they cede their entire Louisiana territory to Spain – an ally who has been forced to surrender both Cuba and the Philippines in the Seven Year’s War against Britain.

But an entirely different story for France plays out south of America’s borders, in the colony of Saint-Dominigue.

The colony lies on the island of Hispaniola, first claimed for Spain by Columbus, and divided in 1697 – with the French owning the western third (Saint-Dominique, later Haiti) and the Spanish owning the eastern two-thirds (later the Dominican Republic).

Saint-Dominique soon becomes the economic jewel in the crown of French holdings in the New World.

It does so on the backs of some 800,000 African slaves who are abducted by their French masters to raise sugar and coffee crops on vast plantations, later to be replicated in cotton fields across the American south. Various witnesses attest to the gruesome tortures inflicted on the slaves by the overseers:

Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars? Have they not forced them to consume faeces? And, having flayed them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and poniard?

By 1780 these slaves are producing 40% of the sugar and 60% of the coffee consumed across Europe. In turn Saint-Domingue becomes the focal point for all French commerce in the Americas, and wins it nickname as the “pearl of the Antilles.”

But all of this comes to a sharp halt in August 1791 – due to a slave rebellion that lasts over three months and eventually pits up to 100,000 blacks against their plantation masters. During this period, an estimated 4,000 whites are killed and hundreds of sugar, coffee and indigo plantation are overthrown.

Reports on the savagery of the slave reprisals – marked by rapes, torture and mutilations – are circulated widely, and strike terror in the minds of plantation owners, including in America, for decades to come.

The rebellion is led by two Black men, Toussaint Louverture, and his lieutenant, and later successor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Relatively little is known for sure about Toussaint’s background, beyond the fact that he is born on Saint-Domingue, around 1740, and is a slave, presumably a house servant, on a plantation until 1776, when he becomes a free man. Along the way he picks up some education (perhaps from Jesuit missionaries) and learns to speak and write French. According to his own account, he also accumulates enough wealth to rent a small coffee plantation and becomes a Freemason.

Toussaint is apparently moved by the spirit of the French Revolution, and offers his services behind a slave rebellion, initiated by a Voodoo priest, which has broken out against the plantation owners in August 1791. He announces his intent late in that month:

Brothers and friends, I am Toussaint Louverture; perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in St Domingue. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers, and fight with us for the same cause.

Your obedient servant, Toussaint Louverture, General of the armies of the king, for the public good.

He quickly exhibits the skills of a natural born military commander and civilian leader, and maneuvers through a host of challenges to emerge as head of a functioning government that controls Saint-Dominque for a decade.

On July 7, 1801, he promulgates a new Constitution for the colony. It does not declare outright independence from France, but bans slavery (“all men are born, live and die, free and French”) and announces that he will retain the title of governor-general for life.

May 6, 1802

Napoleon Captures Toussaint But Fails To Regain Control Over Haiti

When Napoleon learns of Toussaint’s bold Constitution, he decides the time has come to restore French control over Saint-Dominigue – and, perhaps, to also venture back into America.

As always, Napoleon is exceedingly devious in his approach, on both counts.

His first step toward America lies in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso, on October 1, 1800, whereby Spain returns Louisiana to France. This is followed by the November 30 Mortefontaine Treaty with Adams, ending the “Quasi-War” and hopefully lulling the Americans into dropping their guard.

In January 1802, he makes his move against Saint-Dominique.

He sends his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc and a force of 20,000 troops to the island, along with an assurance to Toussaint that his intentions are entirely peaceful. But hostilities quickly break out, and Toussaint’s forces fight back ferociously.

The battles continue until May 6, 1802, when Toussaint meets with Leclerc and works out an apparent cease-fire agreement. But Toussaint’s subordinate, Dessalines, turns on him, and he is put under arrest by Leclerc. His response includes this warning to France:

In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep

Toussaint – known by now as “the black Napoleon” – is put on a ship back to France and imprisoned once there. He is subjected to harsh treatment and dies in short order, on April 7, 1803.

But the black nation he has created on Saint Domingue lives on after him.

Resistance to the French now falls on Dessalines’ shoulders. Its intensity is flamed by the dual threats of white revenge and a return to slavery for the blacks. Dessalines is also aided by an outbreak of yellow fever that kills Leclerc and decimates the French ranks.

After a significant loss at the Battle of Vertieres on November 18, 1803, the French decide to put their remaining 7,000 soldiers back on ships heading home.

Napoleon has had enough for the moment in the Americas, and refocuses all of his energy and resources against a planned invasion of Britain.

Meanwhile Dessalines names himself Emperor of Saint-Domingue and oversees a bloodbath that wipes out all white plantation owners who do not swear allegiance to his rule. His reign is, however, fleeting, and rival black factions assassinate him in 1806, and break the country into the Kingdom of Haiti to the north and a republic to the south – both headed by blacks.

Given these unsettled conditions, along with fears expressed by American slave owners, Jefferson refuses to grant formal recognition to Saint-Dominigue. The former French colony does, however, manage to retain its independence over time, and makes Haiti the oldest republic run by blacks in the western hemisphere.