Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

Chapter 266: Major Robert Anderson’s Heroic Move To Sumter Shocks All Sides

December 26, 1860

Major Anderson Takes It Upon Himself To Concentrate At Ft. Sumter

With all of Charleston calling upon the state militia to seize the harbor forts, Major Robert Anderson awaits orders from Washington that will allow him to leave his assigned post at Ft. Moultrie and move to Ft. Sumter.

His patience finally runs out, and he decides that the December 21 telegram saying he should “exercise sound military discretion” is sufficient cause to act.

He develops a plan to concentrate all of his men and movable arms at Sumter, and hopes to execute it on Christmas Day, under cover of the holiday celebrations. But the city is hit with a downpour, and he delays until December 26.

His first deception involves loading women and children at Ft. Johnson onto three schooners – along with a hidden cargo of provisions and weapons – and sending them in the direction of his home base at Ft. Moultrie, before diverting them at the last second to land at Sumter. This passes without incident.

As evening approaches, Anderson informs his staff of his intent to shift all 60 men in the garrison to Sumter that night. He assigns Captain John Foster and surgeon Samuel Crawford and several others to form a rear guard, with orders to fire the fort’s five heavy Columbiad cannons at the rebels, should they try to impede his boats. If not, they were to spike the guns and follow the crossing.

Captain Abner Doubleday forms his troops and has them row the one mile from Moultrie to Sumter. He is followed by Captain Truman Smith’s company, then by the rear guard, and other boats carrying more supplies.

By nightfall, the full contingent in the fort includes 10 officers and 75 enlisted men, another 55 laborers who have been working there and are deemed to be “loyal” to the Union, and roughly 40 women and children. He also has provisions that he hopes can last for 40 days.

This is far from an ideal outcome, but at least Anderson feels secure for the time being.

That’s because Ft. Sumter is an engineering masterpiece, with construction beginning in 1829 and enhancements ongoing in 1860. Its foundation is a natural sandbar in mid-channel, which had been covered by some 70,000 tons of New Hampshire granite. This supports a five-sided fort, 190 feet in circumference, with concrete walls 5 feet thick and almost 50 feet tall.

When Anderson arrives it boasts 60 cannon, albeit almost all pointed out to sea rather than back toward the surrounding land. With diligent work over the next three months he will reposition 51 of them to target the hostile batteries that surround him.

Anderson sends a telegram to Washington, reporting his move.

I have the honor to report that I have just completed, by the blessing of God, the removal to this fort of all of my garrison…as necessary to prevent the effusion of blood.

December 27, 1860

Anderson’s Move Stuns The White House

Buchanan first learns of Anderson’s move when Southern Senators Jefferson Davis and Robert Hunter show up at the White House on December 27 to demand an explanation.

After Secretary of War confirms the news, the President tells his visitors:

I call God to witness – you gentlemen better than anybody else know that this is not only without but against my orders. It is against my policy.

They respond by accusing him of breaking the “December 10 agreement” to maintain the status quo in the harbor, and demand that he sack Major Anderson and return the Sumter garrison to Ft. Moultrie.

An evening cabinet meeting to formulate a response leads to a clash between War Secretary John Floyd, on his last day in office, and Secretary of State Black. When Floyd’s calls for abandoning all the forts in Charleston, Black fires back accuses Floyd of cowardice.

An ever reluctant President finally sides with Black in supporting Anderson’s move.

December 27, 1860

South Carolina Responds To Anderson’s Movement By Seizing The Other Forts

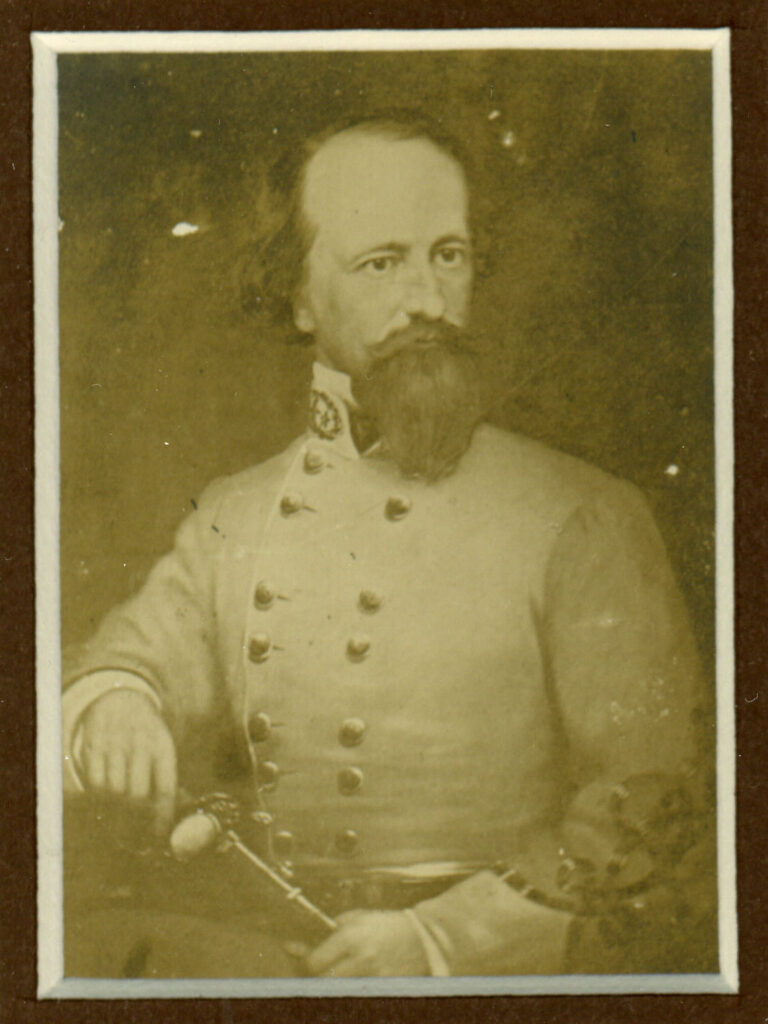

South Carolina Governor Francis Pickens is also outraged by Anderson’s and immediately sends Colonel Johnston Pettigrew to meet with Anderson at Sumter. In response to the demand to return to Ft. Moultrie, Anderson replies:

I cannot and will not go back

To punctuate his refusal, Anderson orders the band to play the Star Spangled Banner as Pettigrew exits the fort.

Hearing the news, Pickens orders out the state militia to seize the other federal forts, beginning with Castle Pinckney.

At 4pm on December 27, 1860, Pettigrew and his troops arrive there to find Lt. Dick Meade manning the facility by himself. When Pettigrew begins to read aloud a proclamation from the Governor to assume control of the fort, Meade interrupts, saying that he does not recognize Pickens authority in the matter. Once he has occupied the site, Pettigrew offers Meade a “parole,” but Meade declines and, in the military courtesies of the era, he is allowed to rejoin Anderson at Sumter.

With Pinckey secure, Lt. Colonel W. G. DeSaussure and a 200 man militia force occupy Ft. Moultrie without opposition, while other raiders take Ft. Johnson and the Charleston arsenal.

Once the Stars & Stripes have been lowered and the Palmetto flag of South Carolina hoisted, a first red-line is crossed in the national conscience. The rhetoric of secession becomes the reality of an overt, albeit still relatively passive, act of war. The United States is no longer one nation, and that fact will soon hugely amplify the level of anger and hostility felt throughout the North.

From December 27, 1860 forward, the possibility for a compromise becomes almost impossible.