Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Chapter 8: Debt Plagues The New Congress Of The Confederation

1781-1787

The Congress Of The Confederation Is Born

In March 1781, the Second Continental Congress gives way to what becomes known as the “Congress of the Confederation” or “The United States in Congress Assembled,” operating under the Thirteen Articles framed in 1777.

At that time, the war with Britain remains very much in doubt. Cornwallis’s army is still rampaging across Virginia and the French fleet has not yet committed to supporting Washington and LaFayette. So “managing the conflict” gives purpose and focus to the body.

However, by the end of October 1781, the victory at Yorktown makes it quite clear that America will soon emerge victorious — and the standing army shrinks from 29,000 soldiers in 1781 to 13,000 by 1783.

Once the Treaty of Paris is finalized in September 1783, many see the “relevance” of the Federal Government as receding since its powers — limited to declaring war, making peace, signing treaties, and printing money – seem already accomplished.

The President of the “Congress Assembled” at the time is Samuel Huntington of Connecticut, who has previously signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. He serves until July 1781, when Thomas McKean of Delaware succeeds him.

But the position of President is largely ceremonial and the consensus is that government decisions should reside with the individual States – in accord with the wishes of the Anti-Federalist politicians.

Each state is headed by a Governor – among them men like Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Rutledge of South Carolina, Hancock of Massachusetts, Clinton of New York and Reed of Pennsylvania who will continue to shape America’s destiny.

State Governors As The Confederation Phase Begins

| State | Name | Served |

| Connecticut | Jonathan Trumbull | 1769-84 |

| Delaware | John Dickinson | 1781-83 |

| Georgia | Myrick Davies | 1780-81 |

| Maryland | Thomas Sim Lee | 1779-82 |

| Massachusetts | John Hancock | 1780-85 |

| New Jersey | William Livingston | 1776-90 |

| New York | George Clinton | 1777-95 |

| North Carolina | Abner Nash | 1780-81 |

| Pennsylvania | Joseph Reed | 1778-81 |

| Rhode Island | William Greene, Jr. | 1778-86 |

| South Carolina | John Rutledge | 1779-82 |

| Vermont | Thomas Chittenden | 1778-89 |

| Virginia | Thomas Jefferson | 1779-81 |

One issue, however, will prevent the total withering away of central government. That issue is financial debt.

1783-1787

The War Debt Becomes A Major Challenge

Fighting the Revolutionary War has proven immensely costly to both sides.

For Britain the estimate is 250 million L, more than enough to antagonize its tax-payers, sack the Prime Minister and eventually lead to capitulation. For the American Congress the tab is pegged around $150 million – in a nation whose treasury probably has no more than $12 million in “hard money” (gold and silver) in 1775, as the first shots are fired.

To pay for wars and other spending, advanced eighteenth governments typically rely on three sources of revenue – collecting taxes, selling assets, and floating interest bearing bonds.

But Anti-Federalist sentiment dominates the 1777 Articles of Confederation, and it has no interest in granting the central government “authority to lay and collect taxes.” British abuse of this “taxing power” is what prompted the war in the first place, and the colonists do not intend to repeat this outcome on their own.

So, under the Articles, any tax collection will be left up to each individual State, with the expectation that a portion of the revenues will be shared with the Continental Congress to support the war effort. In effect then, the States are asked to “donate” some of their tax revenue to Congress – a path that, in practice, fails miserably over time.

A second revenue source, selling assets, involves auctioning off left-over federal land, but state rivalries over ownership make this a contentious affair

Congress does enjoy some success with the third option, selling bonds – collecting money now in exchange for a promised return of both principal and interest at a future date certain. The risk here for lenders is that the Americans might lose the war and be unable to pay off. Despite this, some bonds are sold domestically – often to wealthy patriots (e.g. Washington and George Clinton) investing in the nation’s survival – and abroad, to nations like France, Spain and the Netherlands, which all had an interest in seeing Britain lose the war.

One American plays a particularly noteworthy role in this kind of fundraising. He is Haym Solomon, a Polish born Jewish businessman. He emigrates to New York City in 1775, becomes a wealthy international trader and joins a “Sons Of Liberty” chapter in protest against the crown. Then, he is sentenced to death by the British, but escapes to safety in Philadelphia. Once there he is instrumental in securing French loans, as well as rallying domestic support. George Washington himself calls repeatedly for Solomon’s help, whenever his army is desperate for supplies. Sadly Solomon never recoups his loans after the war, and dies in poverty at age 44 years in 1785.

After failing to cover the cost of the war with these three conventional paths, Congress turns to an alternative option as a last resort.

The Federal Government begins to print its own money.

1783-1787

Simply Printing Money Fails To Solve The Problem

During the colonial period, America’s economy has utilized three forms of “money:”

- Commodities acting as money, such as plugs of tobacco or beaver pelts, used in bartering.

- Minted coins called “specie,” most often Spanish dollars, comprising 24 grams of pure silver.

- Paper notes, issued by banks in each State, denominated in pounds, shillings or pence, and redeemable upon demand for a fixed quantity of “specie,” coined silver or gold.

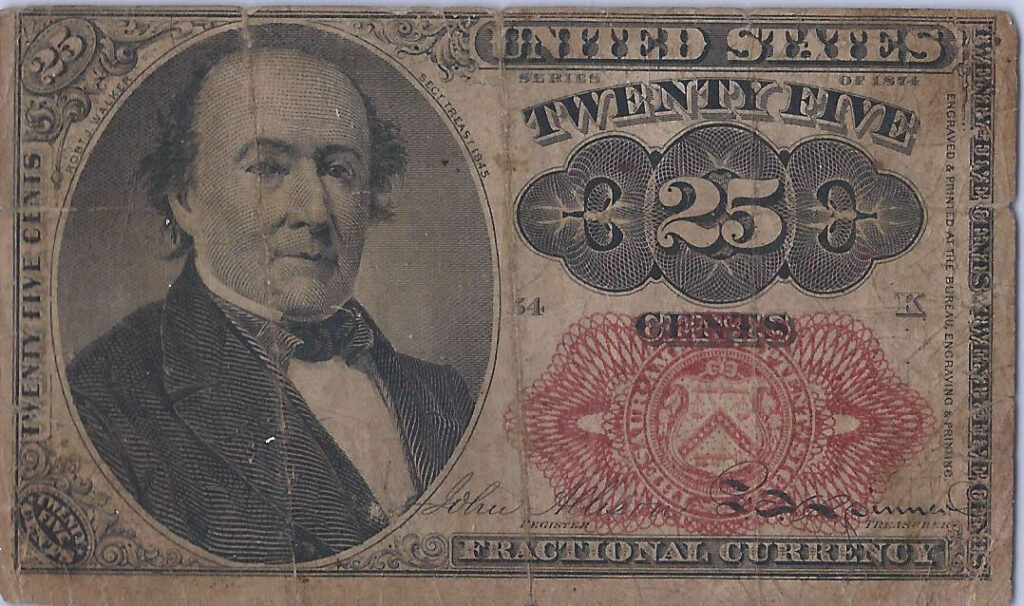

The war, however, forces the desperate Congress to come up with a fourth form – printed “bills of credit” that will become known as “continentals.”

Between 1776 and 1783, “continentals” with a face value totaling some $240 million will be put into circulation by order of Congress. Denominations run from 1/6th of a dollar on up to $80, with variations in between.

The government will use this new money to pay for all things needed to fight the war – gunpowder, armaments, supplies and soldiers. As such, they keep the army and the nation afloat from year to year.

But these “continentals” will turn out to be a sham form of money. The reason being that, unlike prior soft money, holders of the new bills are not guaranteed the right to redeem them for hard assets, silver or gold coins.

Without this “backing in specie,” suspicions build about the actual worth of the “continentals” – and as more flood into the market, “inflation” effects drive their purchasing power well below their asserted “face value.”

What was a $1.00 bill of credit in 1776 drops in worth to around $.58 by 1778 and to about $.11 in 1780. Thereafter the bills become the butt end of jokes, as in “shoddy goods, not worth a continental.”

Of course astute financial men in Congress, like Ben Franklin, recognize the inflated “continentals” for what they are – a devious way around the “direct tax” prohibited in the Thirteen Articles.

Thus when the Federal Government buys a barrel of gunpowder with a $10.00 face value “continental” actually worth $8.00, it is in effect “directly taxing” the seller $2.00.

Like many a financial charade, the funny money Congress prints does allow the nation to get through the war.

Still, no such sleight of hand can overcome the stark reality that America is bankrupt by 1780.

1782

A Controversial “Central Bank” Proves Helpful

The perils of this bankruptcy are best known to the soldiers fighting the war, especially George Washington and his principal aide-de camp, Alexander Hamilton. Both men are Federalists, and together they push Congress to name a “Superintendent of Finance” to restore the American economy.

Their pick for the job is Robert Morris, and Congress approves him in 1781.

Morris is born in 1734 in Liverpool and emigrates to Maryland at age thirteen to work with his father as a “factor” (middleman) in the international tobacco trade. He masters his craft and moves to Philadelphia where he apprentices with Charles Willing, a wealthy financier, who serves as Mayor of the city before an early death.

In 1857 Morris and Thomas (Charles Willing’s son), create the firm of Willing, Morris & Co., which becomes wildly successful in everything from marine insurance to real estate to shipping ventures, including the slave trade.

By 1776 their stature around Philadelphia leads both men to be named delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Although they both oppose the Declaration of Independence, they play a crucial role in financing the war once it begins.

Morris recognizes right away that funding the Congress will depend upon linking public men who understand government with private men who operate in the world of finance.

With this goal in mind, Morris proposes that a “central bank” be chartered – to effectively manage the assets and debts of the Federal Government, as well as establish “credible backing in specie” for the money supply.

He titles this “The Bank of North America” and seeks approval from Congress to form a private corporation to run it. Start-up funds will come from investors who will receive 1000 “shares” in the company in return for every $400 they put in. In effect then, this central bank will operate like any other joint-stock corporation.

Resistance to this idea comes immediately from the Anti-Federalists. They fear that a federal bank will erode the power and policies of Congress by putting too much financial influence into the hands of an elite class of private investors. Besides, men like James Madison argue that the Articles of Confederation actually prohibit Congress from chartering any corporations, that being the province of the States.

Despite this opposition, the desperate circumstances surrounding the debt are such that Congress backs the central bank, and it opens on January 4, 1782. Its first president is none other than Morris’s long-time partner, Thomas Willing.

While Willing’s son-in-law purchases 9.5% of the bank’s shares at the first offering, 63% of the shares come from foreign investors in France and the Netherlands brought in by Morris. Over time, this heavy stake in America held abroad will also become a sore point with the Anti-Federalists.

Once up and running, The Bank of North America will become a major success. It attracts investors and builds a sizable war-chest of money to help deal with the debt. It helps stabilize the true value of the money supply, by assuring that new bills of debt are backed by reserves of silver and gold. It reassures other nations that America’s finances are sound enough to warrant renewed international commerce.

Growth Of State Banks Chartered To Print “Backed” U.S. Dollars

| 1783 | 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

| 0 | 1 | 15 | 49 | 131 | 163 | 353 | 190 | 494 |

1785

The Land Ordinance Of 1785 Also Helps Finance The Government

One other development – The Land Ordinance of 1785 — will also help the Federal Government finance itself over the long-run.

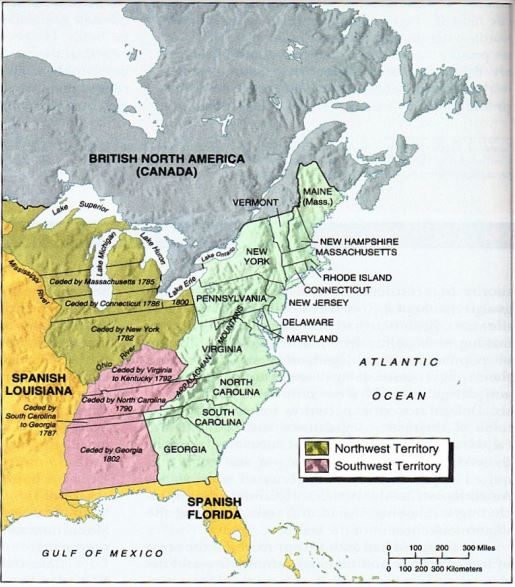

In winning the war, America acquires all of the British land from west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi River. This land represents a very attractive asset, capable of generating needed government revenue, if Congress can figure out “who actually owns” the acreage and how to sell it off.

Ownership Of Eventual US Land In 1783

| Total Sq Mi | U.S. | Spain | Britain |

| 3.09 million | 29% | 61% | 10% |

| East of Miss R | West of Miss + Fla | Oregon |

The issue of ownership is immediately contentious, and heated debates on this point begin way back to 1776 when the Second Continental Congress is drafting the Declaration of Independence and the Thirteen Articles of Confederation.

Seven states claim ownership of the new land, based largely on historical “sea to sea border grants” made between the British crown and the joint-stock corporations who founded their colony.

Original State Claims On British Land West Of Appalachia

| Area | Boundary | Claimed By |

| Northwest Territory | Above the Ohio River | Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York |

| Southwest Territory | Below the Ohio River | Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia |

Predictably the other six “left out” states balk at this arrangement – and announce that they will refuse to ratify the Thirteen Articles of Confederation unless they share access to this land. This threat leads to a compromise whereby the States agree the land is “public domain property,” belonging to the Federal Government, and to be sold to help cover war debts owed by both Congress and the States.

In 1784, the Confederation Congress goes to work on a structured plan for surveying and selling land in the new territories, and eventually creating new states. The challenge goes to a Committee of Five: Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, Jacob Reed of South Carolina, David Howell of Rhode Island and Hugh Williamson of North Carolina.

Together they accomplish the first part of the task, in The Land Ordinance of 1785.

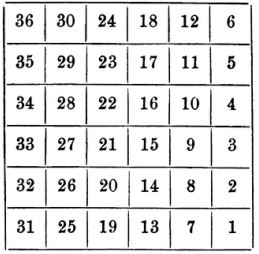

It calls for certified surveyors to map out all of the new land, and then divide it into 6 square mile plots called “townships.” From there each township is broken into 36 equal “sections” of 640 acres. Each section is then “numbered” according to a set schematic, from 1 to 36.

Each section is put up for sale on a first-come, first served basis, at an initial price of $1 per acre, bumped up to $2 in 1796. Buyers could be either settlers or speculators, and anyone owning a “section” was free to sub-divide it for re-sale. The Ordinance also requires that one “section” — #16 – be set aside for a township school, to encourage the spread of public education.

The Act passes Congress on May 20, 1785.

It fails, however, to resolve several important issues related to governance in the new territories – among them the qualifications for becoming a new State and, ominously, whether or not slavery will be permitted or banned.

The slave owner Jefferson attacks the practice once again, as he did in one of the “deleted” sections of the Declaration of Independence. But his efforts to outlaw it in the new territories after 1800 are turned back.

1830

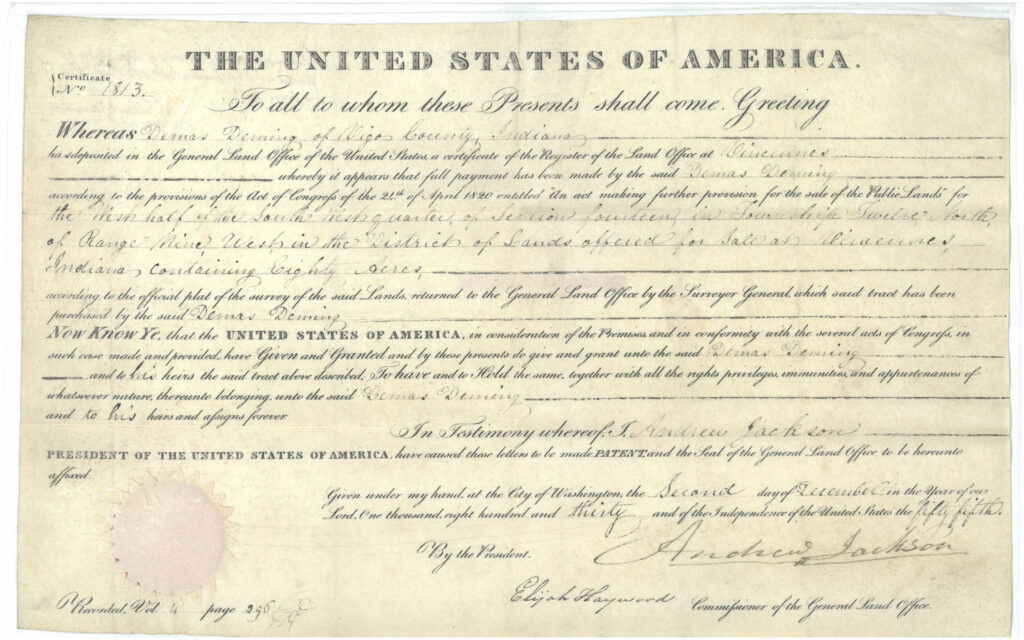

Sidebar: A Typical Federal Land Grant Document

A Land Register Document Selling 80 Acres In Vincennes, Indiana to Demas Deming On December 3, 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson

Mid-1780’s

Debates On The Need For A Stronger Central Government Re-emerge

The Revolutionary War has proven a sobering experience for the new nation – not only for George Washington and his Generals, but also for leaders in the Confederation Congress.

It has tested – and found wanting – the theory in the Thirteen Articles that the independent States will act together effectively around big challenges like war. Neither the men nor the money needed from the States arrives when it is needed.

While the war is eventually won, it is the French who finally make the difference at Yorktown.

America meanwhile enters the war as a remarkably prosperous country and exits it with severe financial and economic problems.. Best estimates available from scholars of the Confederation period show that annual per capita income drops by 22% across the entire nation – from $86 per person in 1775 to $67 in 1800.

The South is hit particularly hard by the war, and its agriculturally-based economy will never regain the regional edge it enjoys in 1775, despite the fabulous wealth concentrated in the “planter class.

Estimates Of Real Per Capita Income During The Confederation Era

| Year | New England | Mid-Atlantic | South Atlantic | Total America |

| 1774 | $57 | $76 | $108 | $86 |

| 1800 | 56 | 68 | 71 | 67 |

| Change | (2%) | (11%) | (34%) | (22%) |

The crushing financial debt experienced by both Federal and State governments reverberates across the entire population. Ex-soldiers are often hardest hit by the economic downturn, having left their farms to chance, and returned with worthless “continentals.” Many have only broken promises of future pay to show for their sacrifices, and Washington fears the result will be domestic unrest.

But the veterans are not alone. Debt is widespread across the land, and many families are unprepared when the State shows up at their doors to collect taxes.

Under the Thirteen Articles, State governments are allowed to levy direct taxes, and they do so in a variety of ways. New Englanders often pay excise taxes on specified goods, taxes on their real estate and occupational taxes. Mid-Atlantic residents pay property taxes and a “head or poll tax” charged to each adult male. In the South, taxes tend to focus more on import and export levies.

Those unable to pay their taxes with “bills of credit” issued by State banks or with minted coins end up in Debtor’s Prison, until they sell off their farms or otherwise pay what they owe.

By the mid-1780’s, those in debt have reached alarming proportions, and revolts begin to break out against tax collectors – Americans this time, not British.

The most famous revolt occurs in January 1787 in Massachusetts, where local farmers plead with the legislature to provide tax relief and to release those held in debtor’s prisons. After being turned down, some 1500 protesters band together under former Continental Army Captain Daniel Shays, and disrupt court hearings and efforts to collect taxes. George Washington hears of this revolt and urges the Governor to act.

Commotions of this sort, like snow-balls, gather strength as they roll, if there is no opposition in the way to divide and crumble them.

On January 27, 1787, the crisis comes to a head. Shay’s men attempt to storm the Springfield federal armory and are met by the 1200 militia troops called out by Massachusetts, under General Benjamin Lincoln, a close associate of Washington’s, leads them. The ensuing battle is brief but bloody, with Shay’s routed men suffering 24 casualties.

While this ends Shay’s Rebellion, the protest has gathered widespread public sympathy, which sets off alarms among members of the Confederation Congress, as well as George Washington, retired at his Mount Vernon plantation. Something must be done to rally and unify the States to escape from its economic woes.

It is Washington’s observation – “we have errors to correct” – that prompts a series of “conferences” at Mt. Vernon and Annapolis, where a consensus is reached around the call for another “Grand Convention”

This Convention will become the first chance for the new nation to exercise its “right to institute a new government,” exactly as promised in the Declaration of 1776!