Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 160: Northerners Rebel Against The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

Fall 1850

Details Of The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act Begin To Sink In

At first, reactions to the 1850 Compromise are muted in the North.

Unlike the South, where economic growth hinges on opening new slave plantations in the west, Northerners feel far removed from, and often indifferent to, events way out in Texas, New Mexico, Utah and California.

That indifference lasts until they begin to experience the effects of one provision in the 1850 Bill, namely the updated Fugitive Slave Act.

The issue of dealing with run-away slaves goes all the way back to Article IV in the 1787 Constitution:

No person held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labour, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labour may be due.

It is revised in 1793 at the insistence of Southerners to clarify that all children of enslaved mothers are, by definition slaves, to define the process of reclaiming runaways, and to set penalties on those who would impede the returns.

In 1842 the Supreme Court’s decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania rules that the 1793 federal law takes precedent over an 1826 state law protecting runaways living in Free States.

What renews the issue in 1850 is a shared belief among slaveholders that escapes are on the rise, and that the North is not only ignoring the problem but, in the case of the abolitionists, encouraging it. Thus, the updated 1850 Act which demands active participation of Northern magistrates – and average citizens – in rounding up and returning runaways to their owners. The new bill comprises ten detailed sections, highlighted as follows:

Details Of The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

| Section | Calling For: |

| 2 | Territorial Courts have the right to appoint commissioners with power to act. |

| 3 | The number appointed can expand on behalf of dealing with runaways. |

| 4 | Commissions shall grant proven owners the right to reclaim their slaves. |

| 5 | It is the legal duty of local marshals – and local citizens – to aid in identifying and capturing and returning all run-aways. |

| 6 | Reasonable force may be applied to secure targeted slaves; trials will be conducted to decide their fate; they are prohibited from testifying in their own defense, and any opposition to carrying out the court’s decision is disallowed. |

| 7 | Anyone who obstructs the process shall be subject to penalties, including fines up to $1,000 paid to the court and six months in jail, along with civil damages of $1,000 per slave involved paid directly to the claimant. |

| 8 | Local marshals and judges shall be paid for their services on each case, the amount being $10 if the decision is to return the accused to slavery or $5 if the claim is denied. Additional fees will be paid for other expenses (lodging, feeding, court attendance, etc.) |

| 9 | Local marshals are responsible for escorting convicted runaways back to the original claimant, employing whatever support is required to complete the task. |

When the contents and implications of this act begin to sink in across the North, a backlash materializes.

This is no longer about happenings far away in the new west, but instead right here and now in their own towns and cities. Even for those indifferent to the fate of black people, the notion of Southern bounty hunters, armed with shotguns and chains and wandering around their neighborhoods, is alarming – as is the legal demand to actively participate in the process, under the threat of fines.

Other Northerners who do oppose slavery are appalled by the act, regarding it as both brutal and a violation of simple justice. They are particularly drawn to Section 6, which prohibits the accused from speaking out in their own defense, and Section 8, which rewards judges with $10 for deciding in favor of the plaintiff (claimant) versus only $5 for siding with the defense (the accused black).

As the act goes into effect and Southern agents begin to appear in the North, the backlash gains momentum.

Sidebar: Simplified Text Of The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

Section 2. That the Superior Court of each organized Territory of the United States shall have the same power to appoint commissioners

Section 3. That the Circuit Courts of the United States shall from time to time enlarge the number of the commissioners, with a view to afford reasonable facilities to reclaim fugitives from labor, and to the prompt discharge of the duties imposed by this act.

Section 4. That the commissioners… shall grant certificates to such claimants, upon satisfactory proof being made, with authority to take and remove such fugitives from service or labor, under the restrictions herein contained, to the State or Territory from which such persons may have escaped or fled.

Section 5. That it shall be the duty of all marshals and deputy marshals to obey and execute all warrants and precepts issued under the provisions of this act, when to them directed; and should any marshal or deputy marshal refuse to receive such warrant, or another process, when tendered, or to use all proper means diligently to execute the same, he shall, on conviction thereof, be fined in the sum of one thousand dollars…. And that all good citizens are hereby commanded to aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law, whenever their services may be required, as aforesaid, for that purpose; and said warrants shall run, and be executed by said officers, anywhere in the State within which they are issued.

Section 6. That when a person held to service or labor in any State or Territory of the United States, has heretofore or shall hereafter escape into another State or Territory of the United States, the person or persons to whom such service or labor may be due, or their agent or attorney…may pursue and reclaim such fugitive person… using such reasonable force and restraint as may be necessary…to take and remove such fugitive person back to the State or Territory whence he or she may have escaped… In no trial or hearing under this act shall the testimony of such alleged fugitive be admitted in evidence; and.. the remove (of) such fugitives…shall (proceed) without molestation of (claimants) by any process issued by any court…. Section 7. That any person who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct, hinder, or prevent such claimant… from arresting such a fugitive… or shall aid, abet, or assist such person…to escape from such claimant… or shall harbor or conceal such fugitive… shall, for either of said offenses, be subject to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisonment not exceeding six months, by indictment and conviction before the District Court…and shall moreover forfeit and pay, by way of civil damages to the party injured by such illegal conduct, the sum of one thousand dollars for each fugitive so lost…

Section 8. That the marshals, their deputies, and the clerks of the said District and Territorial Courts…shall be entitled to a fee of ten dollars in full for his services in each case, upon the delivery of the said certificate to the claimant…or a fee of five dollars in cases where the proof shall not, in the opinion of the such commissioner, warrant such certificate and delivery…(along) with such other fees as may be deemed reasonable by such commissioner for such other additional services as.. attending at the examination, keeping the fugitive in custody, and providing him with food and lodging during his detention…

Section 9. That, upon affidavit made by the claimant of such fugitive…it shall be the duty of the officer making the arrest to retain such fugitive in his custody, and to remove him to the State whence he fled, and there to deliver him to said claimant…. And to this end, the officer aforesaid is hereby authorized and required to employ so many persons as he may deem necessary….

1850

Northern Opposition To The Act Intensifies

As expected, the Abolitionists are first to voice their opposition – led by William Lloyd Garrison, who updates readers on the latest cases involving enforcement of the new law on the front pages of The Liberator.

In September, the initial coverage is of a James Hamlet, returned to slavery in Maryland. By year’s end, the paper tracks a total of twenty-one cases, with nineteen convictions against only two releases.

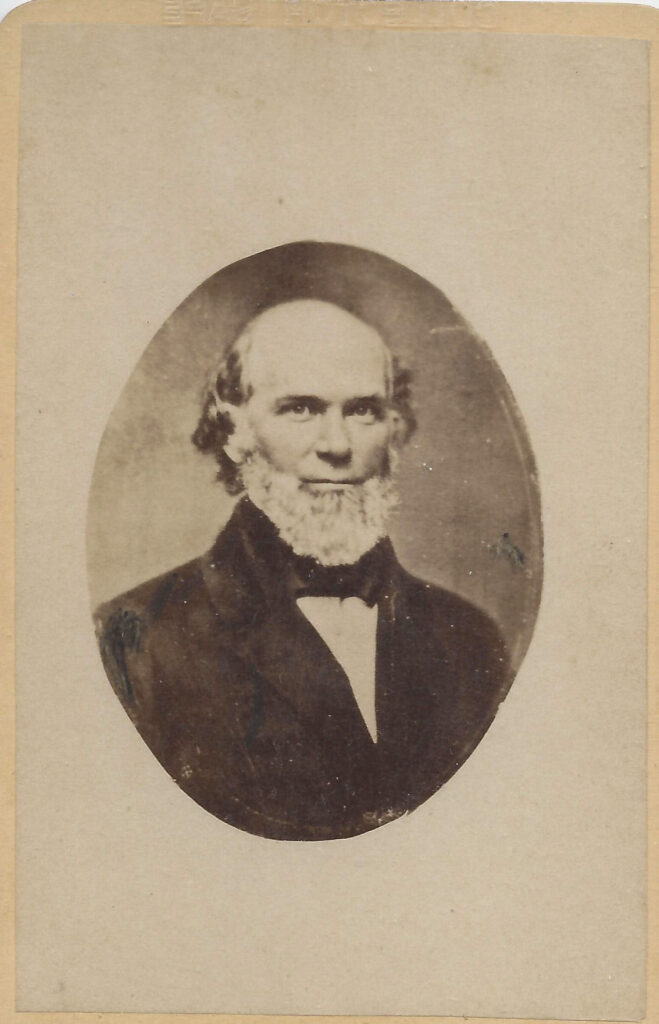

Abolitionist clerics also weigh in, led by the venerable Unitarian minister in Syracuse, Samuel May, and the Unitarian transcendentalist in Boston, Theodore Parker. They are joined by two younger voices that will subsequently be drawn into violent resistance. One is 37 year old Henry Ward Beecher, son of the ultra-conservative Lyman Beecher, who decries slavery from his Congregational Church pulpit in Brooklyn. The other is Thomas Higginson, age 27, precocious attendee of Harvard at 13, whose radical sermons on slavery cost him his post as Unitarian minister in Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1848.

Next come sizable rallies across the North opposing the law and gaining the attention of politicians. In Chicago, the city council declares that it will not cooperate with federal marshals, and the Whig Mayor of New York, Caleb Woodhull, quickly follows suit.

But it is Boston that will become the symbol of active Northern opposition to what many locals characterize as the “Kidnapping Act.”

Their defense centers around a “Vigilance Committee,” founded in June 1841 by Reverend Parker, to protect all blacks – freedmen as well as runaways – from the terrifying threat of being arrested and sent South.

Its first highly publicized case involves George Latimer and his wife who escape from a Virginia plantation only to be spotted and arrested “for larceny” in Boston in October 20, 1842. Abolitionists and freedmen secure representation for the Latimers, but the judge in the case says that federal law requires their return. The matter is soon reserved when their owner accepts a $400 payment to free them.

Another famous case involves a free born man from New York City named Solomon Northrup, a traveling violinist who is drugged and kidnapped after a concert in Washington, DC, and sold into slavery in New Orleans. Northrup is finally freed in 1853 with help from friends in New York, who petition the Governor, Washington Hunt. Upon his release, he pens his memoirs titled Twelve Years A Slave, which sells a remarkable 30,000 copies. Various suits are filed against his kidnappers, but they fail because his standing as a black man prohibits him from testifying in court.

The fates of both Latimer and Northrup are well known to the Abolitionist community, and as soon as the 1850 Act becomes law, they ramp up their plans to resist. In Boston, they will soon be in the national spotlight around the fate of Ellen and William Craft.

December 1850

Ellen And William Craft Make Their Remarkable Escape

Ellen and William Craft are two well-known runaways living in Boston when the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act is signed into law.

Their notoriety rests on the daring escape they execute around Christmas 1848 from a plantation in Georgia.

The scheme centers on the very light-skinned Ellen’s ability to “pass” for white, together with her cleverness as an actress. The couple’s escape plan involves Ellen dressing up as a man, feigning illness, and traveling North “for treatment” along with her black servant, “played” by her husband.

Together the pair use their savings from William’s prior work as a carpenter to purchase train tickets from Macon, Georgia to the coastal city of Savannah.

Neither can read nor write, and both are fearful of being caught out along the passage by their speech patterns. To avoid conversations with other passengers, they hide behind “Ellen’s incapacities.” This works, and they soon repeat the ploy on a steamboat journey that takes them to the Free State of Pennsylvania.

From there they move on to Boston, where they are formally married by Reverend Theodore Parker and William opens a cabinet-making shop.

By 1850 they are hired by the Abolitionists as traveling lecturers to tell their stories about slavery and recount the details of their amazing escape. While William tends to be the narrator, on occasion Ellen breaks the gender barrier at the time and addresses a mixed audience.

This tranquil routine ends in October 1850 when two bounty hunters arrive in Boston from Macon, searching for them on behalf of their Georgia owner, a man named Collins.

When their presence becomes known, The Boston Vigilance Committee springs into action, first hiding the Crafts and then harassing the agents at their hotel, on their way to William’s cabinet shop, and when they attempt to meet with the local constables.

Collins goes so far as to petition Millard Fillmore for support, and the President agrees, even offering up military force to carry out the law.

But then things settle down, with a resolution almost occurring when the Committee offers to pay the bounty hunters to secure the Craft’s freedom. However, both Ellen and William reject this proposal, because they feel it will simply encourage more “agents” to come North for other runaways.

The episode finally ends when the two agents, thoroughly frustrated, give up and head back home empty-handed. To be certain of their safety, however, the Crafts sail on to England, where they reside until 1868 after the end of the Civil War.