Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

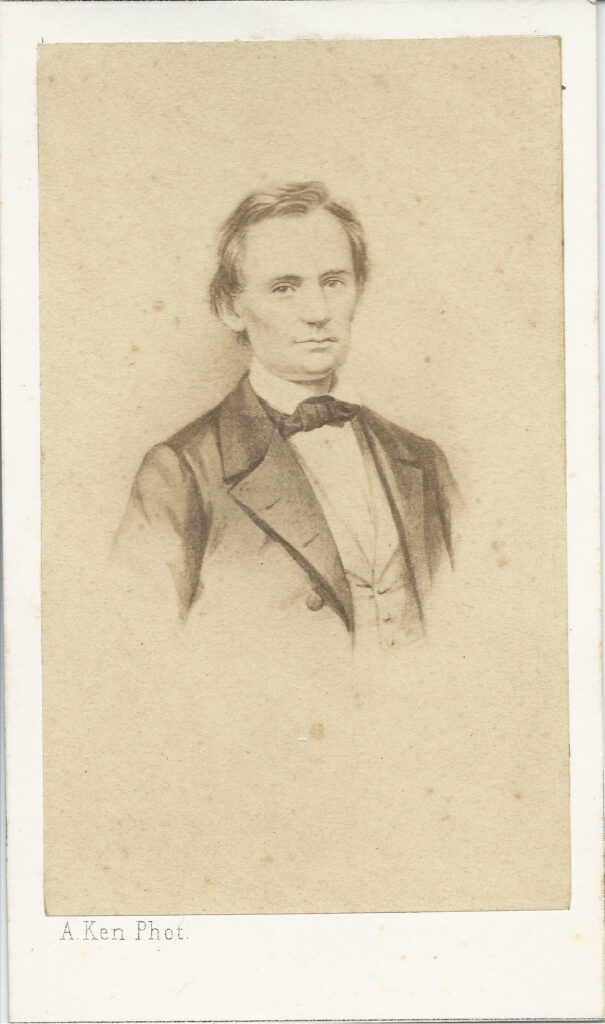

Chapter 85: The Mob Behavior In Alton Also Draws A Public Response From Abraham Lincoln

1809-1830

Abraham Lincoln Becomes A Lawyer After An Unpredictable Youth

At the time of Lovejoy’s murder, Abraham Lincoln is 28 years old, still a bachelor, living in Springfield, Illinois, and just beginning to practice law under John Stuart, after passing the bar in 1836.

His life journey so far has been quite remarkable, given his roots.

He is born in Hardin County, Kentucky, to Thomas Lincoln, an embittered farmer who has lost much of his wealth over disputed land titles, and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, who teaches him “his letters” and shapes his early character. In 1816 Thomas moves his family across the Ohio River into Spencer County, Indiana, where young Abe lives from 9 to 21 years of age. His mother dies soon after the move, and he is subsequently raised by his older sister and then by his step-mother, Sarah, who cherishes him.

While his formal education is close to nil, Lincoln is innately very smart, intensely curious and eager to make his way in the world around him. He masters language through repeated readings of the Bible, Aesop’s Fables,

Pilgrim’s Progress and Shakespeare’s plays, and then writing his thoughts on an easel. He masters daily life by throwing himself into it. His physical presence sets him off from others. He is 6’3” tall, remarkably strong from wielding an ax to split lumber, and noted for outwrestling all comers in town. He is also gregarious, loves debate, and is a natural raconteur. People gather round him to hear his thoughts and share laughter.

Here indeed, at an early age, are the makings of the lawyer and politician he will become. Throughout these early years, slavery is simply an accepted part of his world.

In Kentucky he sees coffles of slaves marching along the road to Nashville near his home. In December 1828, at age 19, and again in April 1831, he is hired to crew flatboats carrying cargo on the Mississippi down to New Orleans – with its omnipresent slave pens and auctions and its unmistakeable messages about the innate inferiority of all Africans.

Lincoln’s initial response to slavery appears to be simple empathy for its victims, and a visceral sense that it is evil. Looking back in April 1864, he will write:

If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel.

But as a young man, growing up where he does, his response is a very familiar passive one.

1831-1837

Lincoln Moves To Illinois and Dabbles In Politics

In 1831 Lincoln heads out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon River to the village of New Salem, Illinois.

Once there he embarks on a string of potential careers, running a general store, serving as postmaster, acting as land surveyor, before deciding to become a lawyer. He begins this final quest, as usual, on his own, reading and re-reading Blackstone’s Commentaries.

During his 5 year stay in New Salem, two other experiences will influence his future. The first provides him with a brief taste of military life.

When Chief Blackhawk and his Sauks attempt to occupy land along Illinois’s northwestern border, Lincoln enlists in the militia on April 21, 1832, and is elected Captain of the 31st Regiment. His ten weeks of duty are largely spent marching and camping, although some believe he participates in a burial detail after the Battle of Stillman’s Run.

After mustering out on July 10, Lincoln returns to New Salem and decides at age twenty-three to enter politics, seeking a seat in the Illinois General Assembly.

He runs as a Whig, given his lifelong admiration for Henry Clay, but finishes eight in a field of sixteen contenders. Despite this initial set-back, he runs again and wins the seat in 1834 and again in 1836.

In 1837 Lincoln is called upon to take a stand on slavery, when the Assembly is asked to vote on a resolution asserting that “the right of property in slaves is sacred…the General Government cannot abolish slavery in the District of Columbia…the formation of abolition societies is highly disapproved.”

The resolution passes 77-6, with Lincoln being one of the six to vote against it — and several weeks later, he and Representative Dan Stone file a protest to its passage, a rarely used device to register strong disagreement.

January 27, 1838

Abraham Lincoln Speaks Out Against Civil Disobedience

In April of 1837, Lincoln moves to Springfield, ready to convert his 1836 law license into a live practice.

Once there, he is drawn to the Young Men’s Lyceum, an educational forum attracting local intellectuals and up-and-coming professionals.

Speaking to this group is a natural for aspiring politicians like Lincoln, and he addresses it on January 27, 1838. The title of his speech is “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,” and he delivers it some ten weeks after the murder of Elijah Lovejoy in nearby Alton.

Many regard this as Lincoln’s his first important public address. It is not about slavery, or even about Lovejoy perse. Rather it warns of two risks facing America’s democracy.

One involves the threat of dictators, like Caesar or Napoleon, substituting their will for that of the people. The other lies in “savage mobs,” imposing their wills on any whom they oppose, as in Alton.

Lincoln declares that any government that tolerates such behavior cannot last.

Whenever the vicious portion of [our] population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure and with impunity, depend upon it, this government cannot last.

A nation has but one path to escape these threats – and that lies in disciplined obedience to the law.

Let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own, and his children’s liberty…Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother…in short let it become the political religion of the nation….

A continued disregard for law signals that “something of ill-omen is amongst us.”

I hope I am over wary; but if I am not, there is, even now, something of ill-omen, amongst us. I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice.

Like the wizened Southerner, John Calhoun, a young Abraham Lincoln is already sensing, in 1838, a fundamental breakdown in the social fabric holding America together.

At this point, however, he has yet to fully plumb the depths of the disorder.

His brief experience in Illinois state government has taught him that it has to do with conflict over “the right of property in slaves.” He also knows that he oppose the notion of slavery on moral grounds.

But how to resolve the matter will absorb him for the remainder of his life.

Unlike John Calhoun and John Brown, the Lyceum speech shows that his answer will not lie in “wild and furious passions.” Instead, Lincoln the lawyer will seek solutions in following the laws, not breaking them.