Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

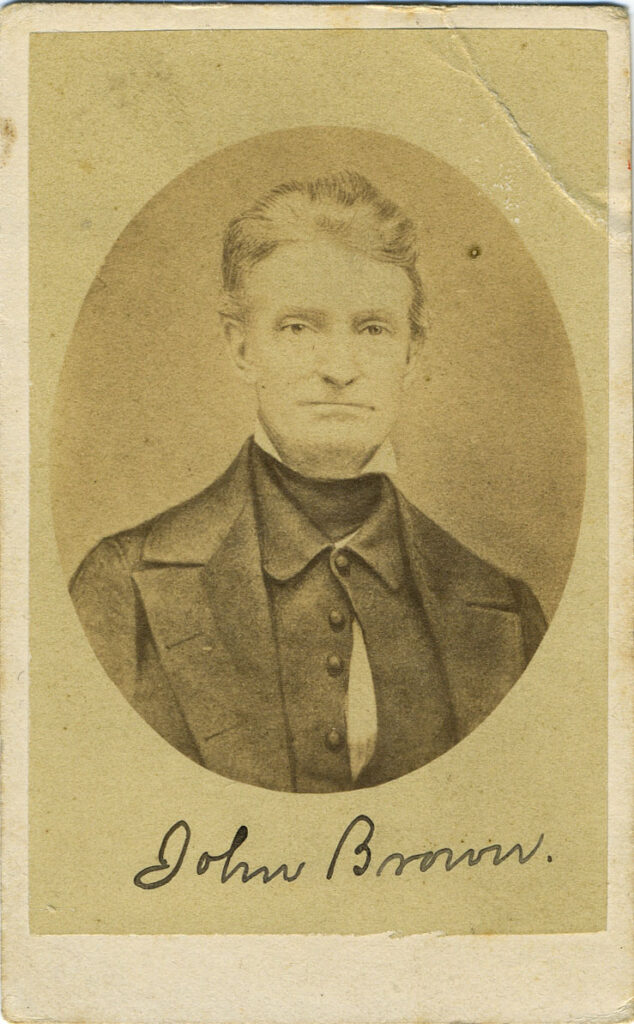

Chapter 84: Lovejoy’s Murder Begets A Fatal Vow From John Brown

The Early 1830’s

John Brown Inherits His Father’s Abolitionist Fervor

No figure in the abolitionist movement will rival John Brown in his willingness to rely on violence to end the practice of slavery. And likewise, no other will quite match his record of living and working up close to blacks on a daily basis, befriending them, and becoming convinced of their capacity to be assimilated into American society.

But for this cause comes John Brown onto this hour. Brown’s early life has been hard, beginning with the death of his mother when he is only eight years old. From then his youth is spent under the iron fist of his father in Hudson, Ohio.

Owen Brown is a strict Calvinist of the old school, dedicated to studying his Bible and trying to achieve daily piety and self perfection. He is also a life-long opponent of slavery, who will subscribe to Garrison’s Liberator, become a trustee of the evangelist Charles Finney’s progressive Oberlin College, and eventually support run-aways on the Underground Railroad network.

Owen Brown will pass along his abolitionist fervor to his son John.

November 1837

John Brown Vows To End Slavery In America

When not praying as a youth, John is working long hours at his father’s tannery — a particularly noxious occupation using human waste and chemicals to convert slaughtered animal hides into leather for shoes, belts, jackets and saddles. Young John Brown will soon master this trade, which he will practice the rest of his life.

At age sixteen, he begins religious studies at the local Congregational Church after publicly repenting and accepting Jesus Christ as his savior. He travels to Litchfield, Connecticut, and enrolls at the Morris Academy, pondering the ministry – until both health and financial difficulties chase him back to Hudson within a year.

In 1820 he marries his first wife, whom he describes as “a neat industrious & economical girl, of excellent character, earnest piety & good practical common sense.” He opens his own tannery, which he runs until 1825, when he buys a 200 acre farm in northwestern Pennsylvania. His plan is ambitious and involves raising and slaughtering the cattle he will use to make and sell finished leather goods.

His dreams, however, fade by 1832, after two shattering events. First, his wife dies following an “instrumented-aided” delivery of a stillborn son, her seventh child over a ten year period. Then Brown himself suffers a prolonged illness that curtails his work and leads to stifling debt.

In 1833, he marries his second wife, the sixteen year old Mary Day, who will eventually bear 13 more children. Their days together will include a daily morning gathering where Brown requires each member of the family to read Bible verses, followed by delivering his own religious admonitions.

As a dedicated Calvinist, Brown is forever searching after God’s plan for his life – and he eventually believes that ending slavery is the answer.

In his autobiography, Brown will write that his antipathy to slavery begins when he is 12 years old, and witnesses a young black boy being “beaten with iron shovels.” As early as 1834, Brown tells his brother Frederick that he is “trying to do something in a practical way for my fellow men that are in bondage.” His initial thoughts turn toward bringing a black youth into his family, educating him and “teaching him the fear of God.”

His business debts mount, and, in 1836 he moves his family from Pennsylvania to a 92 acre farm in Franklin Mills, Ohio, where he again starts up a tannery, largely with borrowed money. But this venture too struggles during the Bank Panic of 1837, and he ends up with even more debt to show for his many talents and hard work.

By this time his abolitionist activities are picking up. He organizes a petition to protest Ohio’s “black codes,” hires freed men to work on his farm, and insists that they be treated respectfully within his local church, much to the dismay of the congregation.

When word reaches him of the Lovejoy assassination, he gathers his family together and reveals his intent to go to wage the Holy War against slavery that will occupy the final two decades of his life.

His oldest son, John Jr., age thirteen at the time, recalls this event years later:

He asked who of us were willing to make common cause with him in doing all in our power to “break the jaws of the wicked and pluck the spoil out of his teeth. Are you Mary (his second wife), John, Jason and Owen?” As each family member assented, Brown knelt in prayer and administered an oath pledging them to slavery’s defeat.

John Brown and his father attend a prayer meeting at the First Congregational Church of Hudson, Ohio to honor Lovejoy’s memory. Toward the end of the service, Brown stands, raises his right hand, and makes a pledge:

Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!

1824-1845

America Struggles With Conflicts Between Spirituality And Materialism

John Brown’s journey from the search for moral perfection of his Calvinist youth to the murderous acts of his adulthood is, in many ways, symbolic of an underlying struggle between spirituality and materialism that is playing out at the time.

On one hand, the Second Great Awakening movement tries to return the nation to its religious heritage, the wish for moral perfection represented by the vision of a “shining city upon the hill,” the hope for eternal salvation.

On the other, a new generation is being drawn ever more intently toward another familiar, but perhaps conflicting vision — the “American Dream.” It is focused not on eternity, but on the here and now, the chance to settle on your own land, to work hard and get ahead, to accumulate wealth and achieve a lifestyle previously reserved for the aristocracy, not the common man. As the Transcendentalist Emerson puts it, by 1835 the daily emphasis is now on “things:”

Things are in the saddle and ride mankind.

The period of reflection marking John Brown’s early adulthood – 1830-1840 – is thus, in many ways, the resumption of a long-term fundamental struggle for the “soul of America.”

The striving for immediate material gains associated with the growing economic successes of capitalism vs. the echoing voices of the original Puritans focused on eternal salvation.

Like Emerson, the astute de Tocqueville, spots this struggle in his observation: “America must remain good to remain great.” To fulfill its promise, it must hold true to its original high-minded religious principles, not retreat into Europe’s corrupting materialism.

In swearing to “destroy slavery,” John Brown asserts the primacy of Calvinist moral righteousness over the injustices of those who would profit economically from human bondage. Surely God’s plan for America cannot tolerate this abomination any longer.

He also goes on to embrace a traditional, but now contentious path to righting wrong — taking the law in his own hands. So it has been when the witches of Salem are summarily burned at the stake; the sitting Vice-President kills the Secretary of the Treasury in a duel; the slaves are beaten and lynched as a matter of course; a minister like Lovejoy is murdered by a mob of neighbors.

His murderous rampages through Kansas in 1856 and Virginia in 1859 will prove to be another test for those who believe that profound social change, such as abolishing slavery, can be achieved solely through legal means, rather than monomania and violence.

1835-1860

Sidebar: Monomania In 19th Century American Literature

The literature of the era is drawn repeatedly to all of these uniquely American themes, especially in the 1835-1855 timeframe.

The Salem born, Bowdoin educated, Nathaniel Hawthorne probes the full range of evils lurking just beneath the surface of the Puritan communities and characters he creates. The Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale is by no means among God’s “elect” few, despite appearances to the contrary.

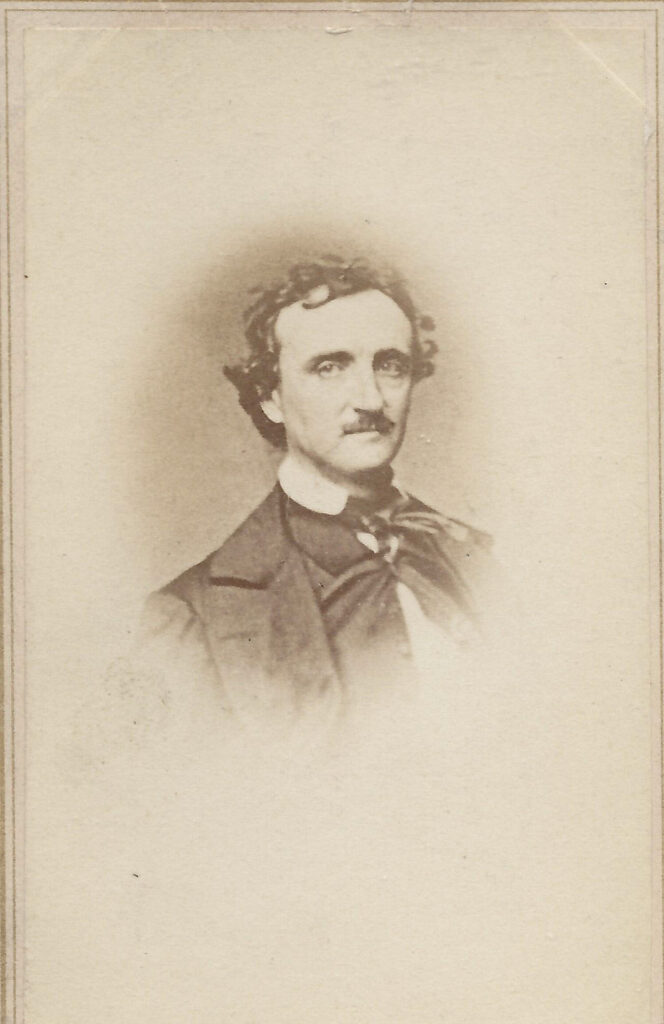

For the Richmond raised Edgar Allan Poe, the focus lies on individual lives ruined by “fixations” that turn into madness and murder. For some the rage traces to an insult from a prior friend. Others are transformed by a fiance’s teeth, a pet cat, the fear of impending illness, an elderly man’s “vulture eye.” For Poe, the path to insane behavior begins with obsession.

But of course, no figure in antebellum American literature will mirror John Brown’s pathology better than Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab, from his 1851 novel, Moby Dick.

Like John Brown, Ahab decides that his fate lies in personally ridding the world of evil, which, in his case, is manifested in the form of the Great White Whale. In striking off Ahab’s leg in a first encounter at sea, Moby Dick becomes for him…

All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs up the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby-Dick. He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down; and then, as if his chest had been a mortar, he burst his hot heart’s shell upon it.

Like John Brown, peg-leg Ahab is seen by his crew as a messianic figure, an avenger out of the Old Testament, the seventh king of Israel, slaughtering the Assyrians at the Battle of Qarqar.

He’s a queer man, Captain Ahab–so some think–but a good one. Oh, thou’lt like him well enough; no fear, no fear. He’s a grand, ungodly, god-like man, Captain Ahab; doesn’t speak much; but, when he does speak, then you may well listen. Mark ye, be forewarned; Ahab’s above the common; Ahab’s been in colleges, as well as ‘mong the cannibals; been used to deeper wonders than the waves; fixed his fiery lance in mightier, stranger foes than whales.

For John Brown, slavery will become his version of Ahab’s great white whale. Infinite evil which must be stamped out, no matter what – and the ends justify the means. From Elijah Lovejoy’s murder in 1837 to his 1858 raid on Harper’s Ferry, John Brown will be on iron rails headed toward his destiny on a scaffold in Richmond. “A grand ungodly, god-like man.” A man obsessed.