Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

Chapter 75: Americans Under Sam Houston Annex Texas

March 1836

A Band Of Settlers Found The Republic Of Texas

Just as Northerners are attempting to “contain” the black population, Southerners make a bold move on behalf of expansion.

Their target in this case is the Mexican province of Tejas, in roughly the same territory that Aaron Burr tried to invade in 1805 before being arrested for treason. (In later years, as the state of Texas, it will become the nation’s number one producer of cotton.)

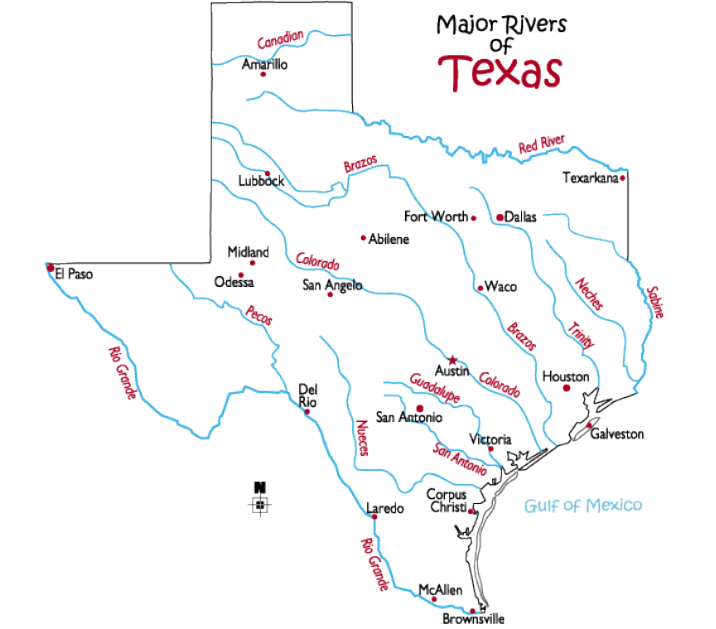

Controversy over ownership of this land dates back to Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. America claims that the western boundary of the purchase extends to the Rio Grande River while Spain draws the line much farther east.

The dispute seems settled for good in 1819 with the Adams – Onis Treaty, which acquires Florida from the Spanish and agrees that American territory ends at the Sabine River line.

But now Spain makes a tactical error. Because it has been slow to challenge the Comanche and Apache tribes and build settlements in Tejas, it negotiates a deal with an American named Miles Austin. This involves granting Austin some land in Tejas in return for beginning the settlement process. The door is now open a crack to American pioneers.

In 1821 Mexico finally wins independence from Spain, and soon thereafter examines conditions in Tejas.

The result is shock and dismay. Austin’s settlers – called Texians — have penetrated all the way from San Jacinto in the east to Goliad and San Antonio de Bexar in the west.

After the Americans try on several occasions to purchase the province from the government, the Mexicans finally decide to ban further immigration, in 1830. But this proves futile and some 38,000 Americans have settled in Tejas by 1835, including 5,000 slaves – even though slavery has been outlawed across Mexico since 1821.

On March 2, 1836, a convention of settlers declare their independence as a new nation, The Republic of Texas, and elect David Burnet, an early settler and political leader, as their interim President.

March 5-27, 1836

Mexico Strikes Back At The Alamo And Goliad

Mexico is already in the process of trying to regain their land well before the Texians declare their sovereignty.

Initial fighting breaks out in October 1835 with the Mexicans intent on driving the invaders back to the US border at the Sabine River.

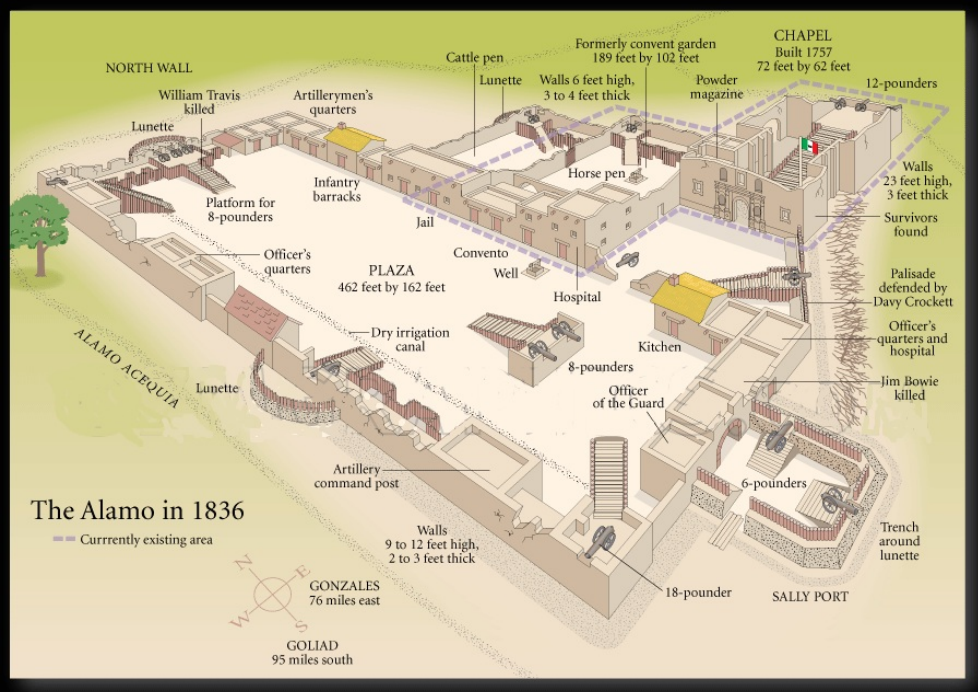

In early 1836, their focus is on taking back two fortified garrisons, one at The Alamo in San Antonio de Bexar, the other at Goliad, some 87 miles to the southeast.

Leading the charge against the Alamo is General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna — a 41 year old commander who has spent the last 15 years in the military and in politics, emerging essentially as dictator of the nation.

Santa Anna sets out toward the Alamo in late December and crosses the Rio Grande on February 12, 1836. Eleven days later he is within sight of the Alamo.

The mission is in poor shape to defend itself. Structurally it is designed to hold off bands of Indians, not an army of 1800 troops, armed with cannon. Conditions are so bad in fact that, in mid-January, Sam Houston sends Sam Bowie to retrieve all artillery and abandon the site. But lacking the needed draft animals for transport, Bowie and Lt. Colonel William Travis decide to try to hold out. They request reinforcements, and a few arrive, including ex-US Congressman, Davey Crockett. These bring his total troop count to roughly 285 men.

Santa Anna surrounds the mission and hauls up a red flag signaling that he intends to take no prisoners.

After a brief siege, Santa Anna attacks the Alamo at 5:30 am on March 5, 1836. The battle lasts for roughly one hour, with the Texians falling back from their outer walls into final defensive positions around the central barracks and church. But they are desperately outnumbered and finally succumb. The entire Texian force is wiped out and their bodies are stacked and burned by the Mexicans.

While Santa Anna is moving overland from the west against the Alamo, a separate Mexican army under General Jose de Urrea is advancing to the southeast, from the Gulf of Mexico, up the San Antonio River toward the town of Goliad, where Colonel William Fannin commands another small outpost he names Ft. Defiance.

Before Urrea arrives, however, Fannin is ordered to abandon the fort and retreat west some 26 miles to the town of Victoria. But on March 19, his force of some 300 men is surrounded by Urrea’s troops on the open prairie. The Texians form a classical Napoleonic square, which holds off the Mexican attacks until nightfall.

Still their situation is hopeless and Fannin surrenders on the morning of March 20 – with some 300 survivors marched back to Goliad as prisoners.

What follows next becomes known as the Goliad Massacre.

General Urrea pleads with Santa Anna on behalf of fair treatment for the Texian prisoners but is rebuffed.

On the morning of March 27, 1836, all 300 men are shot by Mexican firing squads in the town square.

Santa Anna’s ruthlessness here will not be forgotten as the Texians prepare to strike back.

April 21, 1836

Sam Houston Wins Independence for Texas

After the losses at The Alamo and Goliad, the dashing Sam Houston steps in to lead the Texians.

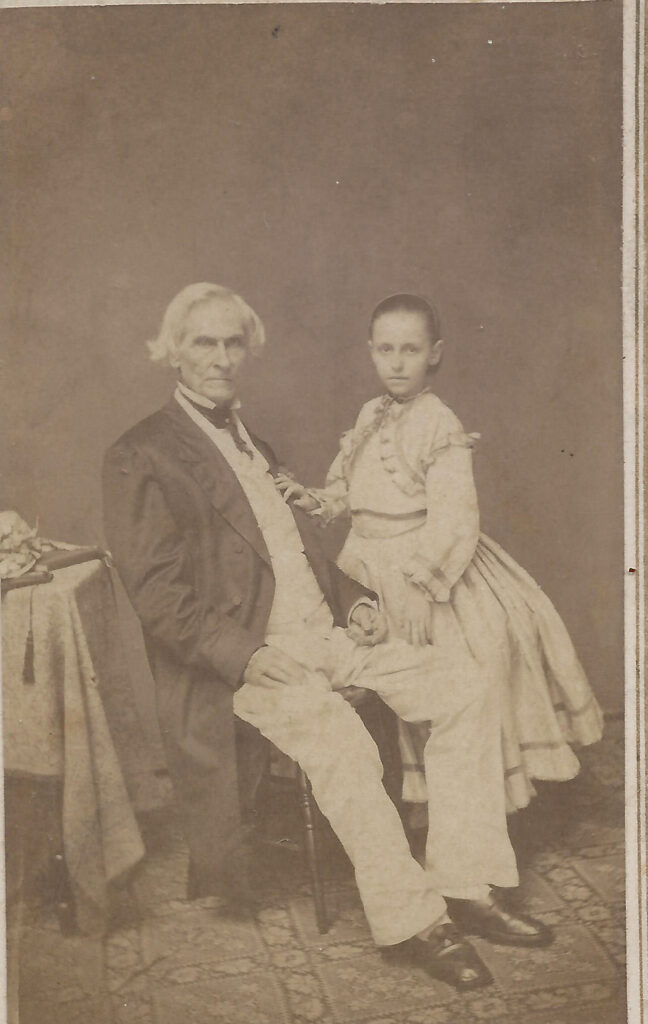

Houston’s life has veered in and out of control over the years. He is born in Virginia in 1793, moves to Tennessee at age 14, runs away from home to live briefly among the Cherokees and returns to fight gallantly in the War of 1812, alongside Andrew Jackson, who becomes his lifelong friend.

After studying law and opening a practice in Tennessee, he is elected to the U.S. Congress in 1823-27, and then becomes Governor from 1827-29. He appears ready to follow in Jackson’s footsteps when his new marriage suddenly dissolves and he is overtaken by drink. He retreats to the wilderness again among the Cherokees of his youth, takes an Indian wife, and earns his Indian name, “Big Drunk.”

Houston suddenly regains his bearings and begins the next chapter of his life by moving to Tejas in 1833. Once there he parlays his skills as a lawyer, politician and military man into a leadership role in the drive for independence. As violence threatens, he is named a Major General in the Texas Army and then its Commander-In-Chief in 1836.

When the far western outpost at the Alamo falls, Houston rallies his small army and attacks Santa Ana’s forces six weeks later on April 21, 1836, at the Battle of San Jacinto. The battle is a 20-minute rout. Houston suffers another of his many war wounds, but Santa Ana is captured and signs a unilateral peace treaty granting Texas its independence.

Houston, henceforth known as “Old Sam Jacinto,” becomes first President of the Republic of Texas on October 22, 1836.

However, the treaty signed by Santa Ana to gain his freedom is rejected in Mexico City, leading to ongoing tension and a threat of more war.

The Texans turn to hopes for annexation by the United States as a solution to their legitimacy.

Summer 1836

Jackson Sends An Emissary To Texas To Assess Conditions

The conflict in Texas and the request for annexation provokes Jackson to send an emissary there in the summer of 1836 to assess the “civil, military and political conditions” and recommend what, if any, action the U.S. should consider taking.

The man chosen for the visit is Henry Mason Morfit, 43 years old, who is born in Norfolk and becomes a practicing attorney before joining the U. S. State Department. Once situated in Texas, Morfit writes a series of ten letters to Jackson over five weeks which describe his findings and “urge against” offering statehood. Two reasons drive Morfit’s opinion.

First, he believes the Mexican army is about to gather in force in the spring of 1837 and that it will be able to overwhelm the Texans. Morfit tells Jackson that a commitment to Texas means a commitment to sending U.S. troops into a war against Mexico.

The old colonists would not by themselves be able to sustain an invasion and, at the same time, supply the means for the war.

Second, the emissary expresses reservations about the motives underlying the entreaty to Washington.

Finally, (there are) suggestions and arguments that this whole enterprise of independence is a mere speculative scheme, concocted and encouraged for the aggrandizement of a few.

Morfit’s main suspicion about the entire Texas “enterprise” is that the Republic is broke and needs federal money to survive.

Summer 1836

Jackson Makes A Crucial Decision Against Annexing Texas

With the input from Morfit, President Jackson faces one of the most consequential decisions of his entire presidency.

He recognizes that the future of slavery is at the heart of matter – with the South desperately hoping for the annexation and eventual admission to the Union of another Slave State.

But he also know that such a move would be regarded by those in the North as a surrender to Southerners and would most likely trigger a repeat of the 1820 conflict surrounding Missouri’s statehood.

He wisely sees this as a potentially serious threat to the Union he is sworn to preserve, and in turn he rejects the offer.

(Ironically his protégé and fellow Tennessean, James Knox Polk, will go ahead and annex Texas in 1845 which leads to the Mexican War and exactly the kind of North-South schism that Jackson feared.)