Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 114: The Question Of Texas Annexation Again Assumes Center Stage

1836-1843

Texas Annexation Stalls Between 1836 And 1843

As John Tyler nears the end of his “accidental” term as President in 1844, he makes a decision that will eventually lead to the dissolution of the Union.

It involves the lingering question of whether or not to annex the Republic of Texas.

Eight years earlier, in 1836-37, Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, both committed expansionists, decide against this move, after Henry Morfit, emissary to the Texas leader, Sam Houston, warns that annexation will result in war with Mexico and renewed national controversy over slavery.

The courtship, however, carries on. The Texans have solidified their territorial hold by March 1837, when the United States officially recognizes them as an independent nation. In January 1838 South Carolina Senator William Preston introduces a bill to negotiate an annexation treaty with Mexico and Texas, but it is vigorously opposed in the House by John Quincy Adams, citing his opposition to warfare and to slavery.

In early January 1839, the Texans finally break off unification talks and decide to go it alone as an independent Republic.

The reaction in Mexico is one of growing hostility toward the American intruders. On September 11, 1842 the Texas town of San Antonio is attacked and occupied. A year later, on August 23, 1843, President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna openly warns the U.S. that annexation would be regarded as a declaration of war.

This warning fails to deter Tyler, who continues to add Texas as another accomplishment in his legacy. He is swept along in this regard by a rising tide of public interest in opening the west.

Among Southern slave owners, such a move is an economic necessity, to grow more cotton and sell more slaves.

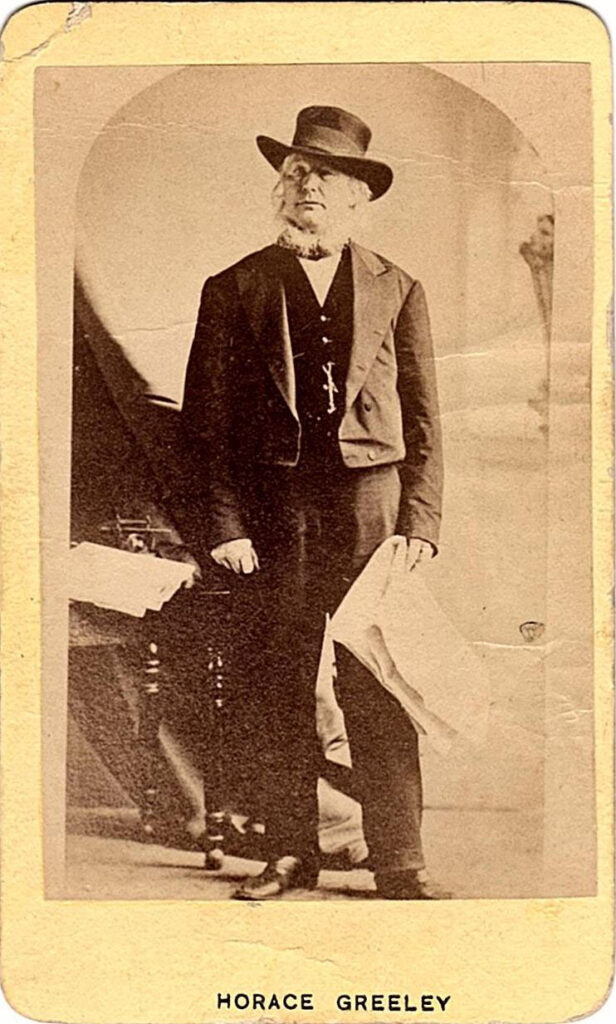

For others, the expansionary fervor seems to build off publicity surrounding the Fremont expeditions and cheerleading from journalists such as Horace Greeley and John L. O’Sullivan.

1839

John O’Sullivan “Manifest Destiny” Vision Resonates With The Public

The cheerleader for westward expansion is John L. O’Sullivan is an Irish immigrant who arrives in the States in 1813 as an infant. He graduates at age eighteen from Columbia University, and takes up law before settling on a career in journalism. In 1837 he founds the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, based in Washington.

The paper unabashedly supports Andrew Jackson and O’Sullivan first articulates his own views on the subject in an 1839 article titled “The Great Nation of Futurity.”

He begins by asserting that the United States represents a fundamental break with the past – the beginning of a new history for mankind in the realm of moral, political and national life.

The American people having derived their origin… on the great principle of human equality…have, in reality, but little connection with the past history of any (other nations)…. On the contrary, our national birth was the beginning of a new history…which separates us from the past and connects us with the future only; and so far as regards the entire development of the natural rights of man, in moral, political, and national life, we may confidently assume that our country is destined to be the great nation of futurity.

Unlike prior societies where humanity was oppressed, America’s core values make it “destined for better deeds.”

What friend of human liberty, civilization, and refinement, can cast his view over the past history of the monarchies and aristocracies of antiquity, and not deplore that they ever existed?

America is destined for better deeds. It is our unparalleled glory that we have no reminiscences of battle fields, but in defence of humanity, of the oppressed of all nations, of the rights of conscience, the rights of personal enfranchisement.

Its “destiny” lies in “manifesting to mankind the excellence of divine principles.”

The far-reaching, the boundless future will be the era of American greatness. In its magnificent domain of space and time, the nation of many nations is destined to manifest to mankind the excellence of divine principles; to establish on earth the noblest temple ever dedicated to the worship of the Most High — the Sacred and the True.

Given this calling, America will become the “great nation of futurity.”

For this blessed mission to the nations of the world, which are shut out from the life giving light of truth, has America been chosen…. Who, then, can doubt that our country is destined to be the great nation of futurity?

O’Sullivan’s themes mirror those of the Puritan preacher, Jonathan Edward, one hundred years earlier.

He goes on to amplify his vision through-out the 1840’s – most notably some six years later in a second more famous article titled “Annexation.” It steps into the realm of foreign policy with an argument that becomes known as Manifest Destiny – the notion that to realize its full potential, America must extend its national borders all the way to the Pacific.

It is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.

O’Sullivan’s call, however, is not for warfare – rather an expectation that other nations, like Mexico, will recognize the exceptional character of America’s democracy and choose to unify peacefully.

April – June, 1844

Benton Momentarily Foils Tyler’s Attempt To Annex Texas

By 1844, Tyler is convinced that annexation of Texas will be popular with the public, and pave the way for his independent party candidacy in the upcoming election.

He order his Secretary of State, Abel Upshur, a Virginian Whig dedicated to the cause of expanding slavery to the west, to open a new round of treaty negotiations with Sam Houston, President of the Texas Republic.

Houston’s primary aim is to avoid conquest by a militarily superior Mexico.

After the 1836 Alamo defeat, he looks to the US as a savior, and certainly, the average Texan always favors that solution. But other political leaders disagree. One is the powerful Miramar Lamar, a Georgian by birth, who wants to rid Texas of Comanches and Mexicans alike and make it a new and independent nation, with borders extending to the Pacific. Over time, Houston is also tempted by this vision, which includes a potentially explosive component — an alliance between Texas and Britain.

Negotiations are well along when Upshur is killed suddenly by the explosion of a naval gun on the USS Princeton being demonstrated during a celebratory outing on the Potomac. To the amazement of all, Tyler names John C. Calhoun, another man without a party, to take Upshur’s place.

Calhoun quickly closes on a proposed treaty, with several key terms, applauded across the South:

- Texas would enter the Union as a state, and not a territory;

- It would be allowed to retain slavery;

- The U.S. would assume its national debts, in exchange for its public lands; and

- The U.S. would be obligated to defend Texas against any attacks by Mexico.

Tyler submits the treaty to the U.S. Senate for approval, on April 22, 1844, first arguing that it is essential to keeping Texas out of the hands of the British. Opponents counter by downplaying this threat, especially in relation to the near certainty that annexation would provoke a costly war with Mexico.

The President now bumbles forward, alienating various constituencies. When he offers to placate Mexico by forgiving $6 million in debt, he undermines the Texan’s standing as an independent republic. From there he plays up the benefits of acquiring new slave territory and voting power for the South, immediately alienating Northern congressmen. Calhoun secretly pushes the point even further, suggesting that the matter comes down to “Texas or Disunion.”

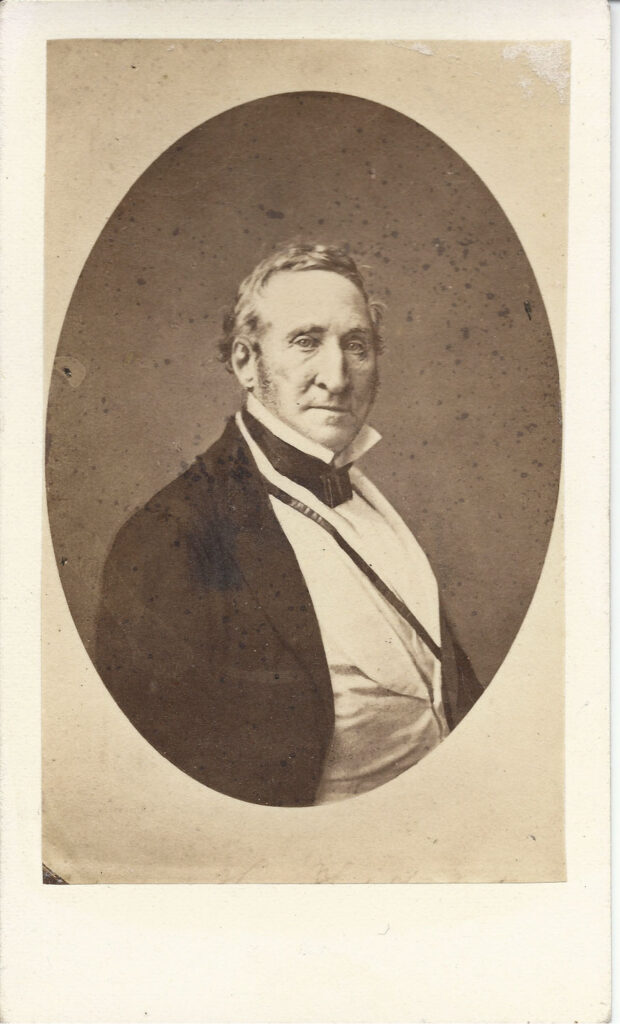

When the treaty debate begins in May, it is the Missouri Senator, Thomas Hart Benton, who leads the opposition.

Benton is a Southerner, a loyal Democrat, Jackson man, and ardent expansionist. He is also a slave-holder, albeit beginning his shift away from support for the institution. Still, he cannot stomach what seems like outright theft of land rightfully belonging to Mexico.

The treaty, in all that relates to the boundary of the Rio Grande, is an act of unparalleled outrage on Mexico. It is the seizure of 2,000 miles of her territory without a word of explanation with her, and by virtue of a treaty with Texas, to which she is no party.

The vote on the treaty occurs on June 8, 1844, and it provides the Whigs, who dominate the Senate, with one more chance to humiliate Tyler. Needing a two-thirds majority for passage, the treaty garners only 16 ayes against 35 nays, with all but one of the 29 Whigs in opposition.

At this point, Texas annexation again feels like a dead issue.

But that is about to change as the election of 1844 nears.

Sidebar: Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton will make his presence known in American politics across nearly four decades – forever on the side of protecting the Union against all external and internal threats.

He is born on a plantation in North Carolina in 1782. As a young man he moves to Tennessee to oversee his family’s 40,000 acre estate, studies law and passes the bar in 1805.

When the War of 1812 breaks out, he volunteers and serves as an aide on the staff of General Andrew Jackson.

Both men share volatile tempers, and Benton is quick to blame Jackson for apparently provoking a duel involving his brother, Jesse. The time for vengeance arrives on September 4, 1813 when Jackson, bullwhip in hand, calls out the two brothers in a Nashville bar. Both draw their guns and fire at Jackson, shattering his left shoulder and almost causing him to bleed to death.

But, remarkable as it seems, the two strong-willed combatants will subsequently make up and become loyal friends for life.

Benton soon moves to St. Louis, where he builds his legal reputation and becomes editor of the Missouri Enquirer newspaper. In 1817 his short-fuse again leads to violence, and he kills Charles Lucas, an opposing attorney, in a duel.

Still his popularity continues to grow across Missouri, and when the state is admitted to the Union in 1821, he becomes its first Senator.

From then on, he is a leading force in Congress, intent on passing Democratic Party legislation, especially in opposition to a federal bank and in favor of hard money. These traits earn him the nickname “Old Bullion,” and explain this reminiscence about his one-time foe:

General Jackson was a very great man. I shot him, sir. Afterward he was of great use to me, sir, in my battle with the United States Bank.

His sharp mind will forever be matched by an equally sharp tongue and a willingness to push his rivals over the edge — as evidenced by a Mississippi colleague who points a pistol at him on the floor of the senate.

Despite his many controversies, Thomas Hart Benton will also be remembered as a principled man, prone to question his own moral compass, especially later on around the propriety of the Mexican War and the practice of slavery. His opposition to expanding slavery into the new west will end his senate career in 1851.