Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

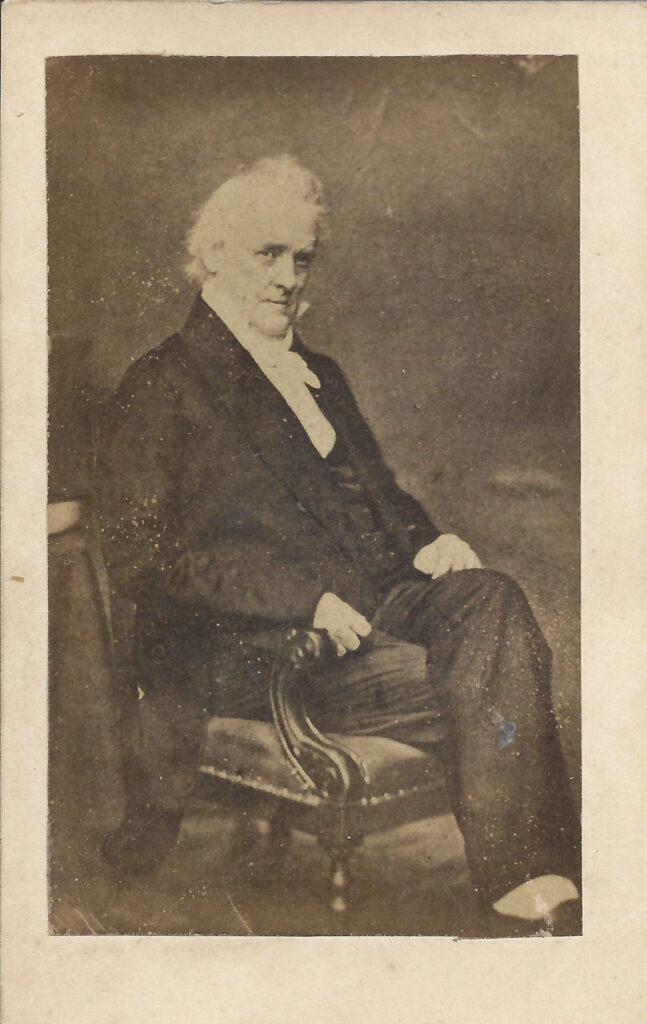

Chapter 259: Buchanan Blames “The People Of The North” For Putting The Union At Risk In His Final Congressional Address

December 3, 1860

He Chastises The North For Its “Intemperate Interference” In Southern Slavery

On December 3, 1869, James Buchanan’s sends his fourth and final state of the union address to Congress. It arrives one month after Lincoln is elected and only seventeen days before South Carolina becomes the first state to secede from the Union.

The message is exceedingly long and self-congratulatory in nature. The implication being that he would be hailed as a great president were it not for the ongoing agitation over slavery issues he inherited.

He begins the address with a tone of contrived optimism, of “plenty smiles throughout the land.”

Throughout the year since our last meeting the country has been eminently prosperous in all its material interests. The general health has been excellent, our harvests have been abundant, and plenty smiles throughout the laud. Our commerce and manufactures have been prosecuted with energy and industry, and have yielded fair and ample returns. In short, no nation in the tide of time has ever presented a spectacle of greater material prosperity than we have done until within a very recent period.

But why then, he asks, does discontent threaten the nation and the Union itself?

Why is it, then, that discontent now so extensively prevails, and the Union of the States, which is the source of all these blessings, is threatened with destruction?

Buchanan places the blame squarely on “the intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery.”

The long-continued and intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the Southern States has at length produced its natural effects. The different sections of the Union are now arrayed against each other, and the time has arrived, so much dreaded by the Father of his Country, when hostile geographical parties have been formed.

This interference has riled the slaves, upset the peaceful “family altar” on the plantations, and forced the South to band together on behalf of their own security.

It can not be denied that for five and twenty years the agitation at the North against slavery has been incessant….The immediate peril arises not so much from these causes as from the fact that the incessant and violent agitation of the slavery question throughout the North for the last quarter of a century has at length produced its malign influence on the slaves and inspired them with vague notions of freedom. Hence a sense of security no longer exists around the family altar.

How easy it would be to end the conflict if only the North would back off and allow the South to exercise its rights around slavery.

How easy would it be for the American people to settle the slavery question forever and to restore peace and harmony to this distracted country! All that is necessary to accomplish the object, and all for which the slave States have ever contended, is to be let alone and permitted to manage their domestic institutions in their own way.

His Solution Is A Constitutional Amendment Validating Slavery

His shifts his attention to the remedies open to the South to protect their rights, one being secession. He argues that the election of Lincoln — by a “mere plurality” and in the context of “temporary causes” – should not by itself be sufficient cause for the South to secede.

This brings me to observe that the election of any one of our fellow-citizens to the office of President does not of itself afford just cause for dissolving the Union. This is more especially true if his election has been effected by a mere plurality, and not a majority of the people, and has resulted from transient and temporary causes, which may probably never again occur.

Instead the South would be “justified in revolutionary resistance” only if Lincoln commits some “overt and dangerous act.”

Reason, justice, a regard for the Constitution, all require that we shall wait for some overt and dangerous act on the part of the President elect before resorting to such a remedy (secession)..But are we to presume in advance that he will thus violate his duty? This would be at war with every principle of justice and of Christian charity. Let us wait for the overt act…In that event the injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union.

But even then Buchanan finds no provision in the Constitution allowing a state to break free – unless the other members in the contract agree to let that happen. As he says, the Union was “intended to be perpetual…and not to be annulled (by) any one of the contracting parties.”

In order to justify secession as a constitutional remedy, it must be on the principle that the Federal Government is a mere voluntary association of States, to be dissolved at pleasure by any one of the contracting parties. If this be so, the Confederacy is a rope of sand, to be penetrated and dissolved by the first adverse wave of public opinion in any of the States…. Such a principle is wholly inconsistent with the history as well as the character of the Federal Constitution.

The right of the people of a single State to absolve themselves at will and without the consent of the other States from their most solemn obligations, and hazard the liberties and happiness of the millions composing this Union, can not be acknowledged

It was intended to be perpetual, and not to be annulled at the pleasure of any one of the contracting parties.

Furthermore, any attempt by South Carolina to seize federal property such as the Charleston forts, will be met by federal resistance.

Then, in regard to the property of the United States in South Carolina…It is not believed that any attempt will be made to expel the United States from this property by force; but if in this I should prove to be mistaken, the officer in command of the forts has received orders to act strictly on the defensive. In such a contingency the responsibility for consequences would rightfully rest upon the heads of the assailants.

Conversely he asks if the Constitution gives Congress authority over “coercing a State into submission” by force, if it attempts to withdraw peacefully without permission? The answer, he finds, is “no.”

The question fairly stated is, Has the Constitution delegated to Congress the power to coerce a State into submission which is attempting to withdraw or has actually withdrawn from the Confederacy?

The fact is that our Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it can not live in the affections of the people, it must one day perish. Congress possesses many means of preserving it by conciliation, but the sword was not placed in their hand to preserve it by force.. This ought to be the last desperate remedy of a despairing people, after every other constitutional means of conciliation had been exhausted.

This brings him to his proposed “solution” which is precisely aligned with the demands of the South. It would require an “explanatory amendment” to the Constitution on slavery, validating “slaves as property,” guaranteeing the right of owners to transport them into all territories prior to statehood, and insuring Northern cooperation in returning run-aways.

This is the very course which I earnestly recommend in order to obtain an “explanatory amendment” of the Constitution on the subject of slavery.

1. An express recognition of the right of property in slaves in the States where it now exists or may hereafter exist.

2. The duty of protecting this right in all the common Territories throughout their Territorial existence, and until they shall be admitted as States into the Union, with or without slavery, as their constitutions may prescribe.

3. A like recognition of the right of the master to have his slave who has escaped from one State to another restored and “delivered up” to him, and of the validity of the fugitive-slave law enacted for this purpose.

This section of the address ends with the totally delusional assertion that his proposal “would be received with favor by all of the States!”

It ought not to be doubted that such an appeal to the arbitrament established by the Constitution itself would be received with favor by all the States of the Confederacy. In any event, it ought to be tried in a spirit of conciliation before any of these States shall separate themselves from the Union.

He Congratulates Himself On His Achievements In Office

After having his say on slavery, Buchanan launches into a review of his many accomplishments in office – believing to the bitter end that these somehow outweigh the fact that the Union is crumbling on his watch.

He begins with his first love, foreign policy, and lists, in agonizing detail, the “most friendly” conditions he has delivered around the globe.

Our relations with Great Britain are of the most friendly character…

With France, our ancient and powerful ally, our relations continue to be of the most friendly character…

Between the great Empire of Russia and the United States the mutual friendship and regard which has so long existed still continues to prevail, and if possible to increase. Indeed, our relations with that Empire are all that we could desire…

With the Emperor of Austria and the remaining continental powers of Europe, including that of the Sultan, our relations continue to be of the most friendly character…

The friendly and peaceful policy pursued by the Government of the United States toward the Empire of China has produced the most satisfactory results…Our minister to China, in obedience to his instructions, has remained perfectly neutral in the war between Great Britain and France and the Chinese Empire.. (The reference here is to the Second Opium War, with the two western powers trying to legalize and dominate the trade in opium and coolie labor.)

The ratifications of the treaty with Japan (was) concluded at Yeddo on the 29th July… With the wise, conservative, and liberal Government of the Empire of Brazil our relations continue to be of the most amicable character…

The exchange of the ratifications of the convention with the Republic of New Granada (i.e. largely the combination of Panama and Columbia) signed at Washington on the 10th of September, 1857, has been long delayed from accidental causes for which neither party is censurable.

Ever the expansionist, Buchanan again pushes for the acquisition of Cuba and its sugar plantations, long a target of Southern slave owners.

Our relations with Spain are now of a more complicated, though less dangerous, character than they have been for many years…I reiterate the recommendation contained in my annual message of December, 1858, and repeated in that of December, 1859, in favor of the acquisition of Cuba from Spain by fair purchase.

The one foreign policy disappointment he sees is in Mexico, where he points to the failure of Congress to send a military force into the interior to end “outrages” committed against American citizens and merchants.

Our relations with Mexico remain in a most unsatisfactory condition… our citizens residing in Mexico and our merchants trading thereto had suffered a series of wrongs and outrages such as we have never patiently borne from any other nation…

I deemed it my duty to recommend to Congress in my last annual message the employment of a sufficient military force to penetrate into the interior…Having discovered that my recommendations would not be sustained by Congress, the next alternative was to accomplish in some degree, if possible, the same objects by treaty stipulations with the constitutional Government.

His litany now shifts to the domestic front. He credits himself with quelling the unrest among the Mormons in Utah – despite the consensus belief that he bowed in the end to the will of Brigham Young.

Peace has also been restored within the Territory of Utah, which at the commencement of my Administration was in a state of open rebellion.

He appropriately mentions his “wise and judicious” management of the economy and his efforts to reduce federal government expenditures.

In my first annual message I promised to employ my best exertions in cooperation with Congress to reduce the expenditures of the Government within the limits of a wise and judicious economy.

I am happy, however, to be able to inform you that during the last fiscal year, ending June 30, 1860, the total expenditures of the Government in all its branches–legislative, executive, and judicial–exclusive of the public debt, were reduced…

He reports the cuts down to the penny:

1858… $71,901,129.77 (fiscal years ending June 30)

1859… $66,346,226.13.

1860… $58,579,780.08

He notes that “not a single slave has been imported” in the last year, and that he has put an end to “filibustering” actions both domestically and abroad. Then come a few final recommendations for the next Congress: fund the transcontinental railroad; increase select tariffs; and establish a fixed date for the election of Congressmen across all states in the Union.

He Makes One Final And Futile Attempt To Explain Kansas

Buchanan knows that his presidency has been severely damaged by his handling of “bloody Kansas” and of the Lecompton Constitution, so he attempts to once again justify his actions.

He begins by saying that he did not create the conflict in Kansas. Instead, on his first day in office, he was handed a “revolutionary government,” attempting to impose the Free-State Topeka Constitution on the entire territory.

At the period of my inauguration I was confronted in Kansas by a revolutionary government existing under what is called the “Topeka constitution.” Its avowed object was to subdue the Territorial government by force and to inaugurate what was called the “Topeka government” in its stead.

Naturally he turned to “the ballot box” as the best way to solve the dispute.

The ballot box is the surest arbiter of disputes among freemen…

But the “insurgent party” refused to participate in votes until January 1858, when it became clear that the anti-slavery party “were in the majority” – thus ending the “danger of civil war.”

The insurgent party refused to vote at either, lest this might be considered a recognition on their part of the Territorial government established by Congress. A better spirit, however, seemed soon after to prevail, and the two parties met face to face at the third election, held on the first Monday of January, 1858, for members of the legislature and State officers under the Lecompton constitution. The result was the triumph of the antislavery party at the polls. This decision of the ballot box proved clearly that this party were in the majority, and removed the danger of civil war. From that time we have heard little or nothing of the Topeka government, and all serious danger of revolutionary troubles in Kansas was then at an end.

Instead of leaving it at that, Buchanan wanders back to the genuine source of the criticism levelled at him all along – his persistent demand that Kansas should be admitted to the Union under the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution. He protests that it was his “duty” to submit the document to Congress for approval.

The Lecompton constitution, which had been thus recognized at this State election by the votes of both political parties in Kansas, was transmitted to me with the request that I should present it to Congress. This I could not have refused to do without violating my clearest and strongest convictions of duty.

From there, however, he proceeds to dig a hole for himself. First, by questioning “if fraud existed” – despite the overwhelming evidence that the Border Ruffians rigged the early elections. Second, by washing his hands of accountability for challenging the veracity of the Lecompton document.

If fraud existed in all or any of these proceedings, it was not for the President but for ongress to investigate and determine the question of fraud and what ought to be its consequences.

He tops that off by walking away from the key platform plank that he ran on in 1856 as a Democrat: the promise that “popular sovereignty” would be the litmus test on whether a new state’s constitution would be for or against slavery. While claiming that he “desired” such a vote, its omission he says was not without precedent.

It is true that the whole constitution had not been submitted to the people, as I always desired; but the precedents are numerous of the admission of States into the Union without such submission.

In embracing the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, he did his “duty” and avoided “disastrous consequences” for Kansas and for the Union.

Had I treated the Lecompton constitution as a nullity and refused to transmit it to Congress, it is not difficult to imagine, whilst recalling the position of the country at that moment, what would have been the disastrous consequences, both in and out of the Territory, from such a dereliction of duty on the part of the Executive.

Thus the story he has told himself all along. Not that his loyalty to the South has led him to overlook election fraud and try to force Congress to approve a constitution that violates the will of the people. Rather that he was simply fulfilling his duty to the nation.

This self-delusional narrative has failed during his entire term and it fails again in this his farewell speech.