Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 42: A Crisis Over Slavery Is Averted By The “1820 Missouri Compromise”

February 13, 1819

Missouri Applies To Become America’s 44th State

On February 13, 1819, a bill is laid before the House of Representatives to authorize the settlers in the Missouri territory to form a state constitution and apply for admission to the Union.

Missouri has grown up around the boom town of St. Louis, which the French settle in 1673. By 1818 St. Louis is a key port for the new steamboat trade along the Mississippi, and it offers its 9500 inhabitants a post office, three banks, a flour mill, several distilleries and a brewery, along with roughly 40 retail storefronts.

As soon as the territory population hits the 60,000 threshold, Missouri is eager to become America’s 23rd state.

At first glance, this seems simple enough. The process required is laid out in the Enabling Act of 1802, and it has been used successfully to admit five new western states from Ohio in 1804 to Illinois in 1818.

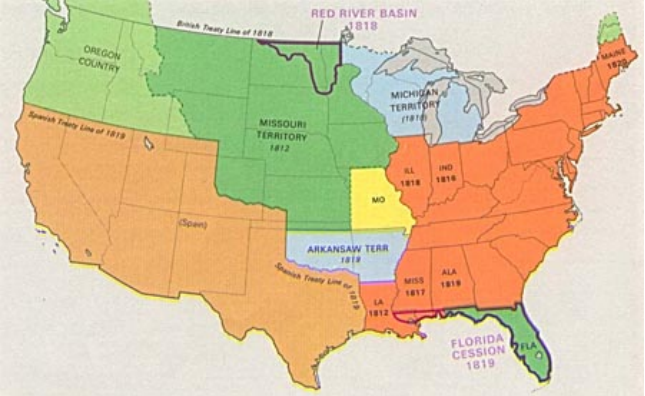

But Missouri comes with a difference. It will be the first state west of the Mississippi River, situated on “new land” acquired in the Louisiana Purchase.

It will also be the first state where the presence or absence of slavery is not determined according to the Ohio River line of demarcation, as laid out in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

As such, it ignites a fresh debate about what “slavery policy” should apply on this new soil. An outcome in favor of extending slavery across the river is crucial to the South!

For two reasons. The first is economic. The old South has bet its future wealth on opening new plantations in the west to buy its excess slaves and to grow cotton. Missouri is a prime prospect for this scenario, but only if slavery is allowed. The second reason relates to political power. If slavery is allowed, the South would gain a 24-22 edge vs. the North in Senate seats and greater leverage over all forms of future federal legislation.

The Southern case is also bolstered by the fact that over 10,000 slaves, about 1 in 6 of all settlers, already reside in Missouri by 1819.

Surely, the argument goes, the federal government has no right to deprive owners of migrating with their existing “property in slaves” into whatever territory they choose.

1607 Forward

Northerners Fear Expansion Of The Black Population

Northern legislators are not, however, ready to go along with the southern plan. Their publicly stated rationales vary widely.

- Some point to a map showing that 90% of the Missouri landmass lies due west of Illinois, a “free state” – under the 1787 Northwest Ordinance line of demarcation traced by the Ohio River.

- Others argue that making Missouri a “slave state” would set a precedent for its western neighbor, the Nebraska territory, drawing plantation owners onto land already set aside for the “relocation” of the eastern Indian tribes.

- A few rail against the South for trying to use Missouri to gain a voting edge in the Senate.

But behind these rationales lies a simpler truth – recognition by northern politicians that their white populations hope to cleanse all blacks, slave or free, from living in their midst.

Attempts to do so are already well established by 1819. “Black codes” discouraging freed men from living in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois are already in place, and “modifications” to state Constitutions begin to materialize. Thus the apparently high-minded first clause opposing slavery in the states…

Neither slavery not involuntary servitude shall be hereafter introduced in this state.

Is followed by a subsequent clause which bans free blacks from taking up residency within state borders:

No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state

The message here is clear – all blacks, slave or free, stay out! They are viewed as a menace to white society, and it is up to the South to deal with “their problem,” not spread it to the North

On February 3, 1819, a New York congressman delivers this same blunt message to his colleagues in an amendment to the Missouri admission bill.

February 13, 1819

The Tallmadge Amendment Sparks A Firestorm In Congress Over Slavery

The congressman is James Tallmadge, Jr., a 41 year old graduate of Brown University, a lawyer and an ex-soldier in the War of 1812. When the Missouri bill arrives on the floor, he is about to end his one and only term in congress, and is away from DC mourning the recent loss of an infant son.

He returns, however, with a proposal, forever known as the Tallmadge Amendment, which seeks to attach the following rider to the bill granting statehood for Missouri:

Provided, that the further introduction of slavery…be prohibited…and that all children born within the said State after the admission thereof into the Union shall be free, but may be held to service until the age of twenty-five years.

In a flash, the floor debate shifts from admitting Missouri to banning the spread of slavery!

For two days, Tallmadge is attacked by Southerners in the House, before he rises on February 16 to defend his proposal, with arguments that will echo all the way to 1861.

He reassures the audience by acknowledging that slavery was thrust upon America by the British rather than initiated here.

Slavery is an evil brought upon us without our own fault, before the formation of our government, and as one of the sins of that nation from which we have revolted.

He also points out that his amendment does not call for abolition in existing states.

When I had the honor to submit to this House the amendment now under consideration I accompanied it with a declaration…that I would in no manner intermeddle with the slaveholding states.

While we deprecate and mourn over the evil of slavery, humanity and good morals require us to wish its abolition, under circumstances consistent with the safety of the white population.

I admitted all that had been said of the danger of having free blacks visible to slaves, and therefore did not hesitate to pledge myself that I would neither advise nor attempt coercive manumission..

Instead, his focus is on opposing the spread of “the evil” into the new territories.

But, sir, all these reasons cease when we cross the banks of the Mississippi, a newly acquired territory never contemplated in the formation of our government, not included within the compromise or mutual pledge in the adoption of our Constitution — a territory acquired by our common fund, and ought justly to be subject to our common legislation.

He expresses shock over the intemperate responses he has experienced.

When I submitted the amendment now under consideration…I did expect that gentlemen would meet me with moderation. But…expressions of much intemperance followed. Mr. Cobb of Georgia said that “if we persist the Union will he dissolved ; and, with a fixed look on me, he told us, “ we have kindled a fire, which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out ; which seas of blood can only extinguish !”

Sir, has it already come to this — that, in the legislative councils of Republican America, the subject of slavery has become a subject of so much feeling — of so much delicacy — of such danger, that it cannot safely be discussed?

But is unwilling to back down, even if it were to mean civil war.

Language of this sort has no effect on me ; my purpose is fixed ; it is interwoven with my existence ; its durability is limited with my life ; it is a great and glorious cause, setting bounds to a slavery, the most cruel and debasing the world has ever witnessed ; it is the freedom of man ; it is the cause of unredeemed and unregenerated human beings.

If civil war, which gentlemen so much threaten, must come, I can only say, let it come!

I know the will of my constituents, and, regardless of consequences, I will avow it as their representative, I will proclaim their hatred of slavery, in every shape.

During the debate, the horrors of slavery have passed by the very windows of the Capitol.

A slave driver, a trafficker in human flesh, has passed the door of your Capitol, on his way to the West, driving before him about fifteen of these wretched victims of his power, torn from every relation, and from every tie which the human heart can hold dear.

The males, who might raise the arm of vengeance and retaliate for their wrongs, were hand -cuffed, and chained to each other, while the females and children were marched in their rear, under the guidance of the driver’s whip ! Yes, sir, such has been the scene witnessed from the windows of Congress Hall, and viewed by members who compose the legislative councils of Republican America.

The slaves are both the greatest cause of individual danger and of national weakness.

Extend slavery, this bane of man, this abomination of heaven, over your extended empire, and you prepare its dissolution.

By your own procurement, you have placed amidst your families, and in the bosom of your country, a population producing, at once, the greatest cause of individual danger and of national weakness.

Some slaves may be contented, but others might seek revenge if given the chance.

When honorable gentlemen inform us, we overrate the cruelty and the dangers of slavery, and tell us that their slaves are happy and contented… they do not tell us, that the slaves of some depraved and cruel wretch, in their neighborhood, may be stimulated to revenge, and thus involve the country in ruin.

Spreading their presence only threatens the white population and order in our society.

It has been urged… that we should spread the slaves now in our country, and thus diminish the dangers from them.. (But) it is our business so to legislate, as never to encourage, but always to control this evil ; and, while we strive to eradicate it, we ought to fix its limits, and render it subordinate to the safety of the white population, and the good order of civil society.

Finally, banning slavery in the new territory in no way violates the 1787 Constitution.

We have been told by those who advocate the extension of slavery into the Missouri, that any attempt to control this subject by legislation, is a violation of that faith and mutual confidence, upon which our Union was formed, and our Constitution adopted.

This argument might be considered plausible, if the restriction was attempted to be enforced against any of the slave- holding states, which had been a party in the adoption of the Constitution. But it can have no reference or application to a new district of country, recently acquired, and never contemplated in the formation of government.

Talmadge closes his rebuttal with a call for House support of his amendment.

Sir, I shall bow in silence to the will of the majority, on whichever side it shall be expressed; yet I confidently hope that majority will be found on the side of an amendment, so replete with moral consequences, so pregnant with important political results.

In one fell swoop, this February 16, 1819, rebuttal to the South by Tallmadge picks the scab off the sectional wounds that threatened in 1787 to derail the effort to arrive at a national Constitution and Union.

The heated exchanges remind many present of those at Philadelphia between Gouvernor Morris, the ardently anti-slavery delegate from Pennsylvania, and his pro-slavery antagonist James Rutledge of South Carolina.

Tallmadge has let the slavery genie out of the bottle and for the next four decades future members of Congress will be left to struggle with this fact.

Two founding fathers weigh in on the debate. In a letter to his wife, John Adams comments:

Negro Slavery is an evil of Colossal magnitude and I am utterly averse to the admission of Slavery into the Missouri Territories.

Meanwhile, from his peaceful mountaintop in Monticello, the 76 year old Thomas Jefferson, recognizes the import of the Tallmadge Amendment:

This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.

February 17, 1819

House Passage Of The Tallmadge Amendment Shocks The South

On February 17, 1819, the Tallmadge Amendment passes the House, with support from Northern and Western congressmen outweighing Southern opposition.

The margin of victory is 87-76 on the clause “prohibiting further introduction” of new slaves and 82-78 on the clause “freeing any born after admission at age 25 years.”

This loss shocks the South.

Its assumption has been that since some 10,000 slaves are already present in the Missouri territory, congress would have to approve the practice as a fait d’accompli.

Instead they are faced with several alarming new realities.

First and foremost, that white people outside the South are ready to resist the introduction of blacks within their state boundaries, for a variety of reasons. Simple racism is one, the conviction that blacks are an inferior species, only 3/5th of a human. Outright fear is another, the belief that blacks will try to kill whites if given the chance. A third centers on western settlers who do not want to compete with rich planters in buying farmland. Then there is a feeling among some that the intrinsic value and dignity of the white man’s labor is diminished by sub-human blacks performing similar tasks under a whip, and for no pay.

A second reality is that the House of Representatives – the people’s house – will henceforth become a forum for voicing opposition to the further spread of slavery. The topic will no longer be off limits as has been the case for three decades.

And a third reality, the unavoidable reality that the make-up of the House is going against the South, as the membership tilts North and West in response to shifts in population density.

Shift In House Of Representative Membership: 1790 To 1820

| Total | North | South | Border | West | |

| 1792 | 132 | 72 | 45 | 15 | 0 |

| 1820 | 205 | 98 | 58 | 22 | 27 |

| Change | +73 | +26 | +13 | +7 | +27 |

February 21 – March 2, 1819

The Senate Rejects The Controversial Amendment

To defend itself, the South looks to the Senate where voting power remains evenly split between the eleven slave states and the eleven free states.

The House bill is brought to the floor on February 21 by Senator Charles Tait of Georgia, who is serving his final year in Congress before appointment as a federal judge.

Vigorous debates follow off and on over the next nine days.

The result, however, is a victory for the South.

The first clause in the Talmadge bill – prohibiting slavery in Missouri – is defeated by a wide margin of 31 to 7.

The second clause – favoring gradual emancipation – is much closer, although still voted down by 22-16.

In turn, the original Missouri Admission bill – minus the Tallmadge amendments — is returned to the House.

But the House is not about to be ram-rodded by the Senate’s action.

A serious threat to the entire statehood process is barely avoided when the House refuses a motion to indefinitely suspend consideration of Missouri’s application. Instead, the lower chamber votes again in favor of the original Tallmadge Amendment bill and returns it to the Senate.

The process is now stalemated, and the 15th Congress adjourns on March 4, 1819 without a final decision.

December 6, 1819

Speaker Of The House Henry Clay Steps Into The Fray

Ten months pass before the 16th Congress is convened on December 6, 1819, and the Missouri question is again taken up in the House. During the hiatus, the issue has been debated across the north, south and west in local legislatures and assemblies.

The expansion of slavery and the black population across the Mississippi has become front and center, much to the chagrin of the South.

After Henry Clay is again chosen Speaker, he takes the lead in searching for a way to move forward on the Missouri admission.

Clay is in his tenth consecutive year of wielding the gavel, and he remains forever suspicious of Monroe’s capacity as President.

After the 1816 election, Clay hopes to be named Secretary of State, “the path to the White House,” but Monroe chooses JQ Adams instead. In turn, Clay refuses to attend Monroe’s inauguration, a sign of the vanity that will both fuel and ultimately inhibit his ambitions. From that point on, Clay will be at loggerheads with Monroe on one issue after another.

But at the moment, with Missouri, the battle is within his own domain, the House, and he intends to solve it.

Clay’s personal positions on slavery are very much akin to Jefferson’s. He owns some 25 slaves, while intellectually regarding the practice as “inhumane.” He is convinced that the Africans are an inferior race who will never be assimilated into white society. The best that could be done for them would be to pay owners for their freedom, then ship them home to Africa, a plan he backs in 1816 as a co-founder of the American Colonization Society. But like so many conflicted slave owners, he opposes all federal mandate that would end the practice.

In the initial floor debate over the Tallmadge Amendment, Clay had been anything but temperate in his response. In fact, he not only says that the proposal violates the Constitution, but also argues that blacks are treated better as slaves in the South than freedmen in the North. Down the road, this initial stance will come back to haunt him in future national campaigns.

However, as he hears the rhetoric in the House heating up on the issue, including a threat of secession from Thomas Cobb of Georgia, Clay the political master, recognizes the need for a peaceful compromise.

What he faces is a sectional, rather than a party, schism. In fact, the original Federalist Party is so weak and disorganized by 1819-20 as to be almost irrelevant to the debate – even though many believe that the Federalist leader, Rufus King, has engineered the entire controversy, using Tallmadge as a surrogate.

Personal philosophy aside, Clay begins to search for an immediate and practical compromise on Missouri. The solution needs to be one that satisfies both the South and North, while not jeopardizing his own presidential aspirations vis a vis JQ Adams, Calhoun and Crawford, and, for certain, Andrew Jackson.

Monroe himself remains distant from the political fray, in fairly characteristic fashion. His only interest lies in reaching a peaceful solution that doesn’t violate the Constitution.

March 2, 1820

Agreement Is Reached On A 36’36” Demarcation Line

Clay recognizes the intemperance he displayed in his initial address to the House, and concentrates now on defusing the anger present in the chamber. A speech from later in his career reveals his down-home approach to tempering the political rhetoric:

We are too much in the habit of speaking of divorces, separation, disunion. In private life, if a wife pouts, and frets, and scolds, what would be thought of the good sense…of a husband who should threaten her with separation? Who should use those terrible words upon every petty disagreement in domestic life? No man …would employ such idle menaces. He would approach with…kind and conciliatory language…which never fail to restore domestic harmony.

But rhetoric alone will not restore harmony in this case. The South sees the North’s effort to contain slavery as an existential threat to its economic survival. They believe, properly, that slavery will either be allowed to expand geographically, or it will wither and eventually disappear.

Solving the impasse will prove complex and involve two key breakthroughs.

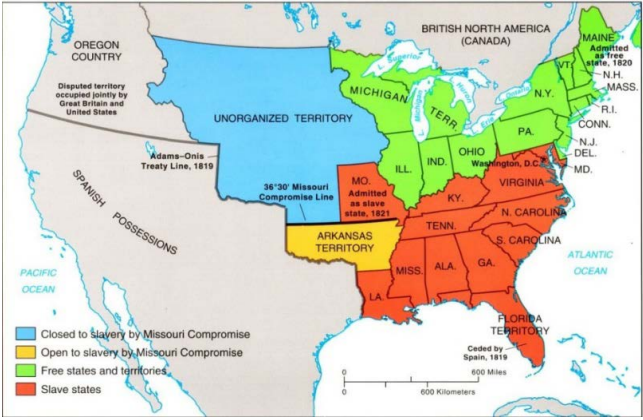

Credit for the first belongs to Clay himself. He recognizes that part of the Northern resistance to allowing Missouri’s entry as a “slave state” is that this would tip the voting power in the Senate in favor of the South. But what if the ongoing efforts to break Massachusetts into two states could be resolved now? Might a quid pro quo – Missouri entering as a slave state and Maine as a free state – swing some Northern votes? This “trade” becomes an important part of the final compromise.

What remains, however, is the real lightening rod issue – will congress vote to “contain” slavery east of the Mississippi River or not?

The eventual answer here comes from the Senate, where Jesse Thomas of Illinois proposes a Solomon-like solution – simply draw a line on the map west from the Mississippi through the Louisiana Territory lands, and declare that all future states north of the line are to be free and south of the line to be slave.

Thomas argues that a hard line worked in the 1787 Northwest Ordinance and it should work again with the new territories.

To sweeten the pot here for the North, Thomas proposes to draw the new line from the southern, not the northern, border of Missouri – at latitude 36’30”. Thus roughly 80% of the remaining Louisiana land will be declared “free” while only the Arkansas Territory will be open to slavery.

On February 17, 1820, a full year after Talmadge offered his amendment, the Senate passes the Thomas “hard line” proposal, a watershed moment in the controversy.

Still the Senate version needs confirmation in the House. On March 2, 1820, members agree to allow slavery in Missouri by a very close 90-87, which includes 14 years from Free State representatives.

The final decision now rests with President Monroe.

He recognizes the volatility of the issues, and has largely stayed on the sidelines as his own 1820 re-election campaign plays out. At the same time, as a southerner and a slave owner, he is troubled by the fact that Congress has weighed into the debate at all. The 1787 Constitution has sanctioned slavery and its presence in Missouri has already been established. But the conflict needs resolution, so he signs the bill into law on March 6.

In the end, the Missouri Compromise legislation appears to settle the slavery question by resorting to the same “hard line on a map” solution of the founding fathers.

The South emerges with a tactical victory – Missouri is admitted to the Union as a slave state. Stability is maintained in the North-South 12:12 state balance of voting power in the Senate.

Balance Of Power In The Senate: After The Missouri Compromise

| Free States | Date | # Slaves | Slave States | Date | # Slaves |

| Pennsylvania | 1787 | 200 | Delaware | 1787 | 4,500 |

| New Jersey | 1787 | 7,500 | Georgia | 1788 | 149,000 |

| Connecticut | 1788 | 100 | Maryland | 1788 | 107,400 |

| Massachusetts | 1788 | 0 | South Carolina | 1788 | 251,800 |

| New Hampshire | 1788 | 0 | Virginia | 1788 | 425,200 |

| New York | 1788 | 10,100 | North Carolina | 1789 | 205,000 |

| Rhode Island | 1790 | 50 | Kentucky | 1792 | 126,700 |

| Vermont | 1791 | 0 | Tennessee | 1796 | 80,100 |

| Ohio | 1803 | 0 | Louisiana | 1812 | 69,100 |

| Indiana | 1816 | 200 | Mississippi | 1817 | 32,814 |

| Illinois | 1818 | 900 | Alabama | 1819 | 47,400 |

| Maine | 1820 | 0 | Missouri | 1821 | 10,200 |

Meanwhile the North’s wins will prove to be more strategic in nature.

Yes, they have given ground on their wish to contain all blacks in the old South — but their long term leverage on the issue has been greatly strengthened in two ways.

First, to the chagrin of the South, the precedent is now established that Congress has the power to make calls about where slavery will or will not be permitted in all new U.S. territory.

Second, the 36’30” demarcation line set for the Louisiana Purchase land all but guarantees eventual dominance by the Northern free states in the Senate. And, in fact, the Louisiana land split will yield nine free states vs. only three slave states.

Some Southern leaders like the astute John C. Calhoun see this potentially ominous handwriting on the wall and try to rally opposition. But most are simply glad with the Missouri state outcome.

August 10, 1821

A Second Compromise Is Needed To Finally Admit Missouri

The Missouri question appears to be over until the new state legislature submits a final constitution prior to the seating of its congressional members.

This document adds one more ominous coda to the entire debate – by seeking to ban all “free blacks” from taking up residence in the state.

In this way slave owners hope to make sure that freedmen do not stir up trouble and rebellions. The U.S. House, however, balks once again.

Clay resorts to quoting Article IV, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution in search of closure.

The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.

Southerners fire back, this time arguing that free blacks are not “citizens” according to the true meaning of the word in the Constitution.

When this debate threatens to further divide the South and North, Clay again works his way out by offering each side a partial victory.

The clause banning free blacks will stay in the Missouri Constitution, but the state will never pass a law to actually enforce it.

After a final flurry, both sides back off, and Missouri officially joins the Union on August 10, 1821.

The outcome on Missouri, however, is no more satisfying for the men of the 15th and 16th congresses than it was for delegates to the 1787 Convention. Once again sectional divisions around slavery have sounded like Jefferson’s “fire bell in the night,” and, instead of resolution, another momentary truce prevails.

The North signals its racist resistance to black people and its intent to try to pen them up in the South, below politically agreed to lines of demarcation.

In turn, the South realizes that protecting the future of its plantation economy will rest not on language in the Constitution, but on winning political battles that expand slavery into new territory west of the Mississippi.

This battle is joined by the Tallmadge Amendment and the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

In effect it marks the moment in time when, for many northerners, the South is transformed into “the Slave Power.”