Section #13 - The 1850 Compromise has Democrats backing “popular sovereignty” voting instead of a ban

Chapter 150: Heated Arguments Stymie The “Omnibus Bill”

February 20, 1850

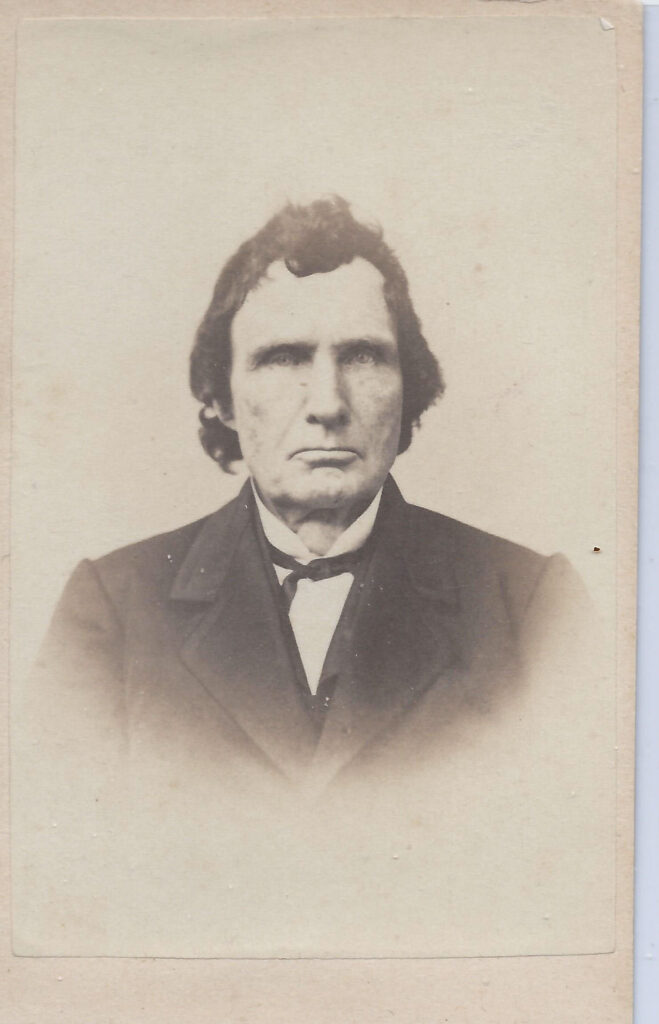

Abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens Opens The Attack On Clay’s Bill

The attack on Clay’s Bill by the Abolitionist forces is launched in the House on February 20, 1850 by Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania.

The stern-faced Stevens arrives in Washington with a reputation as a crusader against institutions he regards as conveying unfair advantages to privileged classes over the common man. This leads to his first foray into politics in the 1830’s as a leading member of the short-lived Anti-Masonic Party.

From there, he turns his fire against the Southern planter class and the practice of slavery.

His commitment to abolition develops gradually. As a young “letter of the law” attorney in 1821, he prevails on behalf of a slave-owner in recovering Charity Butler, a run-away, and her two young children. But the victory gnaws at his conscience, and shortly thereafter he buys the freedom of a slave he encounters in Maryland.

By 1835 he is speaking out in Gettysburg in favor of ending slavery and re-colonization. He attacks the 1836 “Gag rule” and urges congress to end both slave trading and ownership in DC. In an address at the May 1837 state constitutional convention he says:

Domestic slavery in this country is the most disgraceful institution that the world has ever witnessed under any form of government in any age……(If I) were the owner of every Southern slave, (I would) cast off the shackles from their limbs and witness the rapture…in (their) first dance of freedom.

When his Anti-Masonic Party is dissolved in 1838, Stevens first joins Salmon Chase in the Liberty Party, before switching to the Whigs in 1844 and winning his congressional seat in 1848. In that same year he hires a freed black woman, Lydia Hamilton Smith, to be his housekeeper in the capitol and, according to some accounts, his mistress.

Stevens is famous throughout his career for biting oratory, and it is on full display when he rises on February 20 to oppose the 1850 Omnibus Bill. The target of his spleen in this case is one Richard Meade of Virginia, who has just supported the movement of slaves into the new western territories.

Stevens argues that such a move will produce the same economic and moral degradations in the west already evident across Virginia, where “breeding slaves” has become the standard way of life.

It is now fit to be only the breeder, not the employer of slaves…Instead of searching for the best breed of cattle and horses to feed on her hills and valleys…the sons of his great state must devote their time to selecting and grooming the most lusty sires and the most fruitful wenches, to supply the slave barracoons of the South.

Instead of an Omnibus Bill which perpetuates the evils of slavery, Stevens demands an option that abolishes the practice once and for all. He closes his speech with a final dose of spleen for those “Northern doughfaces” who surrender their moral authority to curry favor from Southern politicians and voters.

February 27, 1850

Robert Toombs Pleads For “Good Faith” From The North To Save The Union

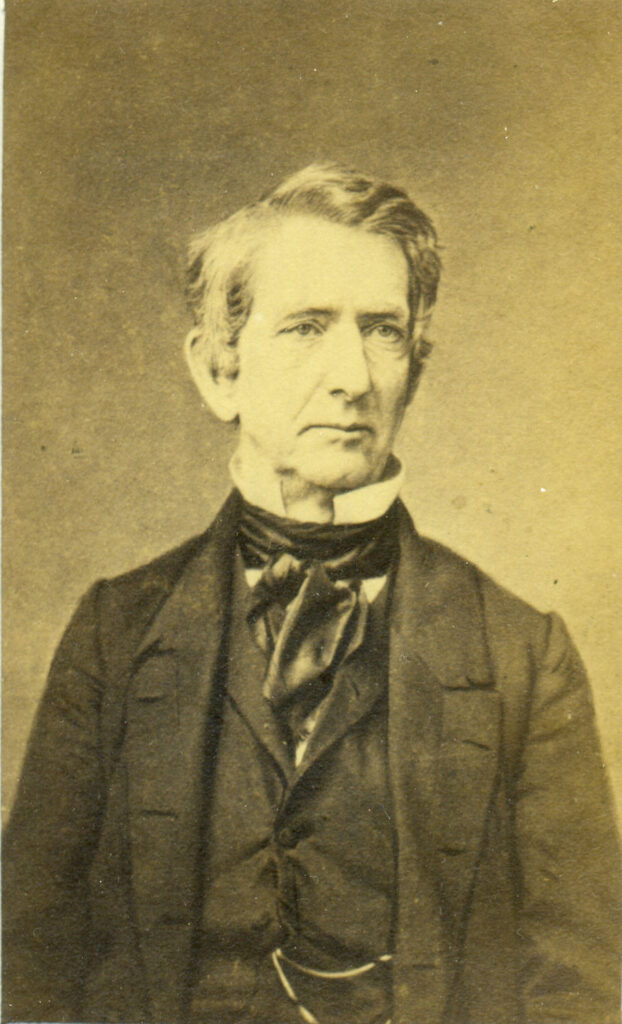

Steven’s criticism is followed by that of another Whig, Robert Toombs, the dissident Georgian, who two months earlier foiled his party’s attempt to elect Winthrop as Speaker of the House.

His message captures the sense of betrayal felt by many Southern Unionists over the entire slavery debate. The 1787 Constitution sanctioned the practice, so how he asks can Northern men of honor turn their backs on the contract?

Toombs powerful February 27 critique begins by acknowledging that the North now enjoys a majority status in America that can be used to “destroy the political rights” of the South.

Mr. Chairman: There is a general discontent among the people of fifteen states of the Union against this government…It is based upon a well-founded apprehension of a fixed purpose on the part of the non-slaveholding states of the Union to destroy their political rights.

The course of events, the increase of population in the Northern portion of the republic and the addition of new states, are about to give the non-slaveholding states a majority in both branches of Congress, and they have a large and increasing majority of the population of the Union.

The only protection left for the minority South lies in “good faith” behaviors by the majority North.

These causes have brought us to the point where we are to test the sufficiency of written constitutions to protect the rights of a minority against a majority of the people. Upon the determination of this question will depend the permanency of the government. Our security, under the Constitution, is based solely upon good faith.

The Constitution does not allow the government to mandate slavery in the new territories, and the South is not demanding that. All it asks is to exercise its right to take its slaves into the new territory.

We do not demand, as is constantly alleged on this floor and elsewhere, that you shall establish slavery in the territories. I have endeavored to show that you have no power to do so.

Slavery is a ‘fixed fact’ in your system.

We ask protection from all hostile impediments to the introduction and peaceful enjoyment of all our property in the territories. Whether these impediments arise from foreign laws or from any pretended domestic authority, we hold it to be your duty to remove them.

Toombs argues that the proposed Omnibus Bill simply strengthens the Northern majority, while offering none of the important protections the South wants and deserves – and hence it cannot be supported.

The bill now before us for the admission of California…settles nothing but the addition of another Non-slaveholding state to the Union, thus giving the predominating interest additional power to settle the territorial questions which it leaves unadjusted.

In this state of the question it cannot receive my support.

In the beginning the South signed on for both the Union and the Constitution; the former cannot be sustained without adherence to the latter.

We are now daily threatened with every form of extermination if we do not tamely acquiesce in whatever legislation the majority may choose to impose upon us.

Gentlemen may spare their threats…the sentiment of every true man of the South will be, we took the Union and the Constitution together and we will have both or we will have neither.

The cry of the Union is the masked battery from behind which the Constitution and the rights of the South are to be assailed

Toombs declares that he has never cast a sectional vote in Congress and never will.

I have never yet given a sectional vote in these halls. Whenever the state of public opinion in my own section…shall incapacitate me from supporting the true interests of the whole nation…I will surrender a trust which I can no longer hold with honor.

The first act of legislative hostility to slavery is the proper point for Southern resistance

The South came to the Union with its slavery and seeks the protection owed it by the North.

You owe us protection (from interference). We had our institutions when you sought our alliance. We were content with them then, and we are content with them now. We have not sought to thrust them upon you. (So) why do you fear our equal competition with you in the territories?

All being asked for is equal treatment of all settlers, then a free election to decide the slavery question.

We ask only that our common government shall protect us both equally until the territories shall be ready to be admitted as states into the Union, then to leave their citizens free to adopt any domestic policy which in their judgment…may best promote their happiness. The demand is just, (but) I see no reasonable prospect that you will grant it.

The action of this House is demonstrating that we are in the midst of a legislative revolution, the object to trample under foot the Constitution…and to make the will of the majority the supreme law of the land.

The duty of Southerners is to stand by the Constitution until it is proven powerless to protect – at which time it must abandon the Union and stand by its arms.

In this emergency our duty is clear: it is to stand by the Constitution and the laws until demonstrated that the Constitution is powerless for our protection.

It will then not only be the right but the duty of the slaveholding states to seek new safeguards for their future security …to prevent the application of the resources of the republic to the maintenance of the wrongful act.

I appeal in the language of a distinguished Georgian who yet lives to arouse the hearts of his countrymen to resist wrong: when arguments are exhausted, we will stand by our arms.

Toombs’s speech captures the key arguments of the Southern dissidents who will go on to form the Constitutional Union Party:

- The institution of slavery was sanctioned in the 1787 contract between the original thirteen states;

- The minority South is now at the mercy of the majority North to abide by the established rules;

- This will require compromises from the North over slavery in order to preserve the sacred Union.

But within this context, Toombs signals his faction’s willingness to accept the “popular sovereignty” option as a fair way to decide on slavery in the west.

March 4, 1850

Calhoun’s Farewell Speech Demands A Congressional Act Affirming The Expansion Of Slavery

For the Fire-Eaters of the South, Toombs’ “solution” is both naïve and inadequate.

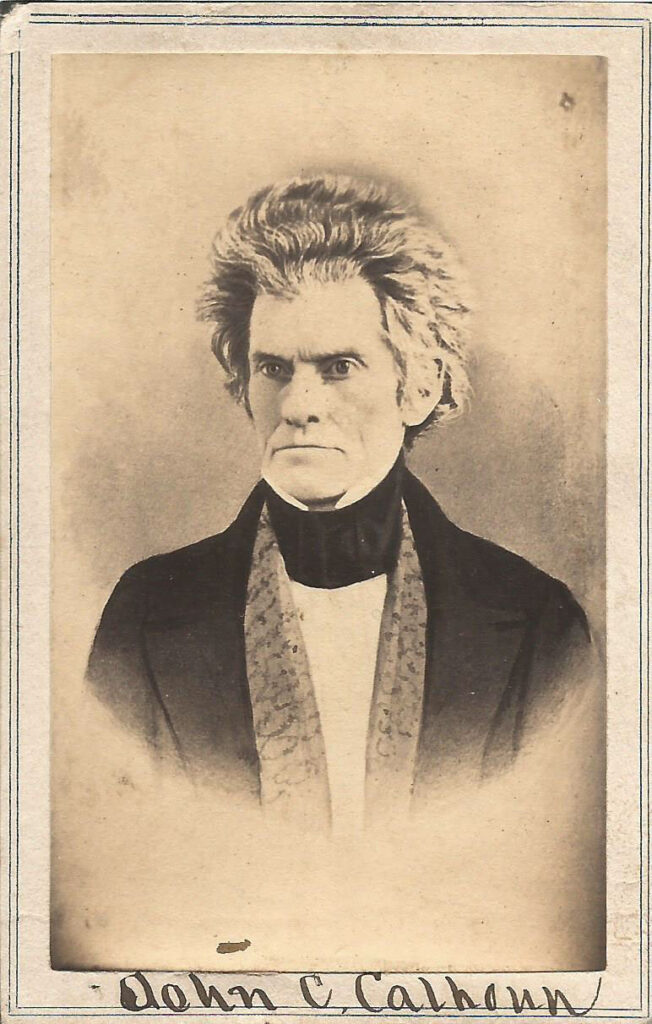

Their leading spokesman is John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who is dying from tuberculosis when it is his turn to open debate on the Omnibus Bill in the Senate.

On March 4, 1850, only 27 days before he succumbs, Calhoun struggles into the chamber for the last time, in a final attempt to “ask for simple justice” for those in the South. He has served his nation over four decades since being elected to the House in 1811. His record includes eight years as Secretary of War under Monroe, seven years as Vice President under Adams and then Jackson, one year as Secretary of State under Tyler, and another seventeen years in congress representing South Carolina.

Despite all this, the one position he wants most, the presidency, has eluded him over questions about his party loyalties. At one moment he is tied to the Federalist Adams and then the Whig Clay. His credentials as a Democrat are tarnished when Jackson turns against him, and when he begins to call for Southern secession. In the end, all sides respect his towering intellect, but few trust his motives or appreciate his overbearing demeanor.

When recognized to speak on the Omnibus Bill, Calhoun is too weak to proceed, and asks his friend, James Mason of Virginia, to stand in for him.

The themes Mason announces are vintage Calhoun. As he sees it, Congress has been usurped by an anti-slavery fringe group that represents less than 5% of all people in the North and is now forcing the South to choose between abolishing slavery and seceding from the Union.

The address begins ominously on the prospect of “disunion.”

I have, Senators, believed from the first that the agitation of the subject of slavery would, if not prevented by some timely and effective measure, end in disunion.

The rest plays out Calhoun’s well known theme that what began with regional “equilibrium” in 1787 has now shifted to Northern dominance and unfair treatment of the South. To prove his point, he says that the boundary prohibitions set on slavery will disqualify the South from access to three-quarters of the nation’s public land.

The United States, since they declared their independence, have acquired 2,373,046 square miles of territory, from which the North will have excluded the South, if she should succeed in monopolizing the newly-acquired Territories, about three-fourths of the whole, leaving to the South but about one-fourth. Such is the first and great cause that has destroyed the equilibrium between the two sections in the government.

In addition he claims that the South has always been deprived of its fair share of incoming federal revenue which has been driven largely through cash generated by its cotton export industry.

The next is the system of revenue and disbursements which has been adopted by the government. It is well known that the government has derived its revenue mainly from duties on imports. The South, as the great exporting portion of the Union, has in reality paid vastly more than her due proportion of the revenue — an immense amount of which in the long course of sixty years has been transferred from South to North. It is safe to say that it amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars — adding greatly to the wealthy of the North, and increasing her population by attracting immigration from all quarters to that section.

Calhoun says that these violations of the South’s “honor and safety” must end if the Union is to be saved – and that the path to “simple justice” lies in abiding by the promises made in the Constitution.

How can the Union be saved? By adopting such measures as will satisfy the States belonging to the Southern section that they can remain in the Union consistently with their honor and their safety. The South asks for justice, simple justice, and less she ought not to take. She has no compromise to offer but the Constitution, and no concession or surrender to make. She has already surrendered so much that she has little left to surrender.

Like Toombs, he says that the time has come to “cease the agitation of the slave question” and restore the original equality between the North and the South.

The North has only to will it to accomplish it—to do justice by conceding to the South an equal right in the acquired territory, and to do her duty by causing the stipulations relative to fugitive slaves to be faithfully fulfilled–to cease the agitation of the slave question, and to provide for the insertion of a provision in the Constitution, by an amendment, which will restore to the South, in substance, the power she possessed of protecting herself before the equilibrium between the sections was destroyed by the action of this government.

Finally he closes with words that move supporters and opponents alike — his final reflection on a long life in public office.

Having faithfully done my duty to the best of my ability, both to the Union and my section, throughout this agitation, I shall have the consolation, let what will come, that I am free from all responsibility.

After this farewell speech, Calhoun returns to the Old Brick Boarding House in DC, where he dies on March 31 at age 68 years. His body is returned to Charleston where parades and speeches at The Citadel and City Hall dominate the city for two days until his final burial at St. Phillips Episcopal Church.

March 7, 1850

Daniel Webster Backs Toombs Call For Northerners To Compromise

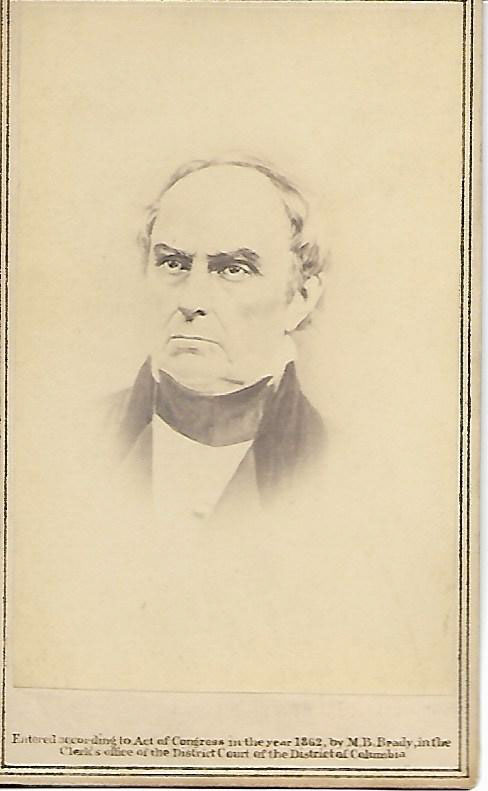

The next critical juncture in the debate belongs to Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, and his support for the Omnibus Bill proves shocking to his many supporters.

“Black Dan” is renowned as a hard drinker and fast liver, with a dominant personality, withering visage and litigator’s voice, and an unerring capacity to forever strike the right emotional chords in making his case.

His brilliant career as a constitutional lawyer has included many such cases, including over 200 appearances before the Supreme Court and a string of landmark victories. Most are antithetical to the South, involving institutions which it distrusts – big corporations and big banks — or backing federal jurisdiction over states’ rights.

- Dartmouth College v Woodward. Corporations do need not serve the public interest in order to enjoy the privileges granted in their charters.

- McCulloch v Maryland. States cannot impose taxes on federal entities, such as The U.S. Bank.

- Gibbons v Ogden. The federal government, not the states, has final power to regulate interstate commerce.

- Cohens v Virginia. Federal courts have the right to review all state decisions in criminal cases.

As a Federalist and then a Whig politician over four decades, Webster has also stood with the New England industrialists for a restrictive tariff and government spending on infrastructure, and against both the Texas annexation and the Mexican War.

When he rises to address the Senate on March 7, he seems an unlikely candidate to assuage Southern fears and to sell Clay’s compromise. But, instead of confrontation, his brief is nothing but conciliatory toward the South.

His opening declaration immediately mesmerizes the audience.

I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American….. I speak for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause.

He decides to simply ignore Calhoun’s attacks on federal taxing and spending policies.

The honorable Senator from South Carolina (argues) that the North has prospered at the expense of the South in consequence of the manner of administering this government, in the collecting of its revenues, and so forth. These are disputed topics, and I have no inclination to enter into them.

Instead he goes right to the issue of slavery, arguing that “men of good conscience” exist on both sides. While some see it as morally wrong, it’s not banned in the New Testament, and, in general, the Southern tradition is to treat those in bondage with “care and kindness.”

The separation of that great religious community, the Methodist Episcopal Church…(shows that) upon the general nature and influence of slavery there exists a wide difference of opinion…

Although not the subject of any injunction in the New Testament, (many feel) slavery is a wrong. The South, upon the other side, having been accustomed to this relation between two races all their lives (and) having been taught, in general, to treat the subjects of this bondage with care and kindness… do not see the unlawfulness of slavery.

From there he lashes out against the Abolitionists, who have “produced nothing good” over twenty years, and whose “agitation and impatience” have retarded “the slow moral improvement of mankind.”

Then, Sir, there are the Abolition societies, (about) which I have very clear notions and opinions. I do not think them useful. I think their operations for the last twenty years have produced nothing good or valuable.

They created great agitation in the North against Southern slavery. Well, what was the result? Public opinion, which in Virginia had begun to be exhibited against slavery, and was opening out for the discussion, drew back and shut itself up in its castle.

They are apt to think that nothing is good but what is perfect, and that there are no compromises or modifications to be made in consideration of difference of opinion or in deference to other men’s judgment.

There are impatient men; too impatient always to give heed to the admonition of St. Paul, that we are not to “do evil that good may come”; too impatient to wait for the slow progress of moral causes in the improvement of mankind…

Not only are these radicals misguided, but also those Northerners who shirk their “constitutional duty” to return escaped slaves to their rightful owners. Here is Webster the full-throated “property lawyer” in action.

I will allude to (one) other complaints of the South, which has in my opinion just foundation; and that is, a disinclination among some individuals and among legislators in the North to perform fully their constitutional duties in regard to the return of persons bound to service who have escaped into the free States. In that respect, the South, in my judgment, is right, and the North is wrong.

I put it to all the sober and sound minds at the North as a question of morals and a question of conscience. What right have they, in their legislative capacity or any other capacity, to endeavor to get round this Constitution, or to embarrass the free exercise of the rights secured by the Constitution to the persons whose slaves escape from them? None at all; none at all.

As he winds down, Webster’s passion is elevated and, once again, he is every inch the Unionist, repeating his 1830 plea to embrace harmony and cast aside secession.

Mr. President, I hear with distress and anguish the word “secession.” I see as plainly as I see the sun in heaven what that disruption itself must produce; I see that it must produce war, and such a war as I will not describe.

Peaceable secession! There can be no such thing as peaceable secession. Peaceable secession is an utter impossibility.

What is to remain American? What am I to be? An American no longer? Am I to become a sectional man, a local man, a separatist, with no country in common with the gentlemen who sit around me here, or who fill the other house of Congress? Heaven forbid! Where is the flag of the republic to remain? Where is the eagle still to tower? Or is she to cower, and shrink, and fall to the ground?

Can anybody suppose that this population can be severed, by a line that divides them from the territory of a foreign and alien government, down somewhere, the Lord knows where, upon the lower banks of the Mississippi? What would become of Missouri? Will she join the arrondissement of the slave States? Shall the man from the Yellow Stone and the Platte be connected, in the new republic, with the man who lives on the southern extremity of the Cape of Florida?

Sir, I am ashamed to pursue this line of remark. I dislike it, I have an utter disgust for it. I would rather hear of natural blasts and mildews, war, pestilence, and famine, than to hear gentlemen talk of secession. To break up this great government! To dismember this glorious country! To astonish Europe with an act of folly such as Europe for two centuries has never beheld in any government or any people! No, Sir! no, Sir! There will be no secession! Gentlemen are not serious when they talk of secession…

And now, Mr. President, instead of speaking of secession, let us come out into the light of day. Never did there devolve on any generation of men higher trusts than now devolve upon us, for the preservation of this Constitution and the harmony and peace of all who are destined to live under it.

In the end, Webster’s March 7 speech comes down on the side of Clay and Crittenden – the old men of his generation — who have lived through the birth of the nation and can’t quite grasp the multifaceted and intractable differences that now divide the North and the South.

Critics claim that he has sold out to the South in the hope of winning a Whig presidential nomination in 1852.

Lloyd Garrison lashes out, accusing Webster of “bending his supple knee anew to the Slave Power.” Other abolitionists follow, most notably the poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, who pens the following:

Of all we loved and honored, nought save power remains.

A fallen angel’s pride of thought, still strong in chains.

All else is gone from those great eyes, the sould has fled,

When faith is lost, when honor dies, the man is dead.

While Webster breathes additional life into the Omnibus Bill, his support of the Fugitive Slave Act portion will cost him dearly, especially in Massachusetts, and, like Calhoun, he will forever be denied his nomination for the presidency.

March 11, 1850

William Seward Cites “A Higher Law” Requiring An End To Slavery In America

With Webster’s support on the record, Clay is optimistic that his Omnibus Bill will be approved in the Senate.

His hopes, however, are shattered exactly four days later when another of his fellow Whigs, William Seward of New York, rises to make his maiden speech in Congress.

The diminutive Seward has led the proverbial “silver spoon in his mouth” life, from his birth into a wealthy NY family, through his first-in-class graduation from Union College and his marriage to Frances Miller, whose father brings him into a thriving law practice and sets the couple up on their lifelong estate in Auburn, NY.

He is first drawn into politics by Thurlow Weed, the newspaperman, joins the Anti-Masonic Party and wins a seat in the NY state senate in 1830. In 1838 he is elected Governor of NY and moves steadily upward to the U.S. Senate in 1848.

His aversion to slavery begins in his youth.

Seward’s father owns slaves, and he mixes with them on a daily basis as a youth. Bondage strikes him as unfair, and this belief is amplified dramatically in adulthood when he and Frances, vacationing in northern Virginia, encounter the realities of slave sales and corporal punishment. After this 1835 trip, Frances becomes an abolitionist, and Seward begins to speak publicly against slavery.

Still he is not yet a dedicated Abolitionist by 1850. Nor is he among the very small band of Assimilationists like Lloyd Garrison, William Birney, Lucretia Mott, John Brown and others who have lived among blacks and can see a day when they are fully integrated into the social fabric.

Instead, like Lincoln, Seward is simply convinced that slavery is morally evil, and is ready to block any actions to allow it to spread outside of the old South.

His opposition in this regard is especially important because he and his supporter Thurlow Weed both have the ear of President Zachary Taylor. The fact that all three want to see the Omnibus Bill defeated shows how fractured the Whigs are on the slavery issue, and how much Clay’s control within the party has eroded over time.

Seward’s speech before the Senate on March 11, 1850, is a stinging indictment of his fellow Whigs, Clay and Webster, and of the proposed Compromise.

He begins by acknowledging Calhoun, and countering his arguments on behalf of “equilibrium” between the states (i.e. half should be free; half slave). The Constitution says no such things, according to Seward.

The honorable senator from South Carolina, argues that the Constitution was founded on the equilibrium (of states) and recognizes property in slaves.

The proposition of an established classification of states as slave states and free states, seems to me purely imaginary. This must be so, because, when the Constitution was adopted, twelve of the thirteen states were slave states, and so there was no equilibrium. …

He then turns to the “slaves are property” assertion and, like several founders back in 1787, hoists the South on contradictions inherent in the 3/5th clause. If slaves were truly property, like cattle or horses, they should count as zero in the census. In arguing for a 3/5ths count, surely the South was seeing them as inhabitants of the country, albeit lesser in value than the whites.

I submit that the Constitution not merely does not affirm the “slave as property” principle, but, on the contrary, altogether excludes it.

The Constitution regards (slaves) as inhabitants, debased below the level of free inhabitants, but only by two-fifths. The remaining three-fifths leaves them still an inhabitant, a person, a living, breathing, moving, reasoning, immortal man.

Seward than makes an assertion which immortalizes his speech – the belief that man is accountable to “a higher law than the Constitution,” the law of the Creator, which dictates against slavery.

But there is a higher law than the Constitution, which regulates our authority over the domain, and … is bestowed upon us by the Creator of the universe. We are his stewards.

And now the simple, bold, and even awful question which presents itself to us is this… shall we establish human bondage, or permit it by our sufferance to be established? Sir, our forefathers would not have hesitated an hour. They found slavery existing here, and they left it only because they could not remove it. There is not only no free state which would now establish it, but there is no slave state, which, if it had had the free alternative as we now have, would have founded slavery.

I confess that the most alarming evidence of our degeneracy which has yet been given is found in the fact that we even debate such a question.

I cannot consent to introduce slavery into any part of this continent which is now exempt from what seems to me so great an evil. These are my reasons for declining to compromise the question relating to slavery as a condition of the admission of California.

In turn, he encourages America to join other Christian nations like Britain and France in gradually abandoning slavery.

Sir, there is no Christian nation, thus free to choose as we are, which would establish slavery. I speak on due consideration because Britain, France, and Mexico, have abolished slavery, and all other European states are preparing to abolish it as speedily as they can.

Seward argues that his position on slavery places him in the moderate camp, unlike others who are threatening sectional harmony – those who demand an overnight end to slavery and those who wish to make it permanent.

We hear on one side demands– absurd, indeed, but yet unceasing–for an immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery–as if any power, except the people of the slave states, could abolish it, and as if they could be moved to abolish it by merely sounding the trumpet loudly and proclaiming emancipation.

On the other hand, our statesmen say that “slavery has always existed, and, for aught they know or can do, it always must exist. God permitted it, and he alone can indicate the way to remove it.” As if the Supreme Creator… did not leave us in all human transactions, with due invocations of his Holy Spirit, to seek out his will and execute it for ourselves.

Here, then, is the point of my separation from both of these parties.

I feel assured that slavery must give way, and will give way… that emancipation is inevitable…

But I will adopt none but lawful, constitutional, and peaceful means, to secure even that end; and none such can I or will I forego.

No free state claims to extend its legislation into a slave state. None claims that Congress shall usurp power to abolish slavery in the slave states. None claims that any violent, unconstitutional, or unlawful measure shall be embraced.

But you reply that, nevertheless, you must have guaranties; and the first one is for the surrender of fugitives from labor. That guaranty you cannot have, as I have already shown, because you cannot roll back the tide of social progress. …

Finally, and naively, Seward dismisses the warnings from Calhoun and Webster that the slavery issue could lead on to disunion.

There will be no disunion and no secession.

Let, then, those who distrust the Union make compromises to save it.

I shall not impeach their wisdom, as I certainly cannot their patriotism; but, indulging no such apprehensions myself, I shall vote for the admission of California directly, without conditions, without qualifications, and without compromise. …

In the end, Seward offers the South nothing at all in exchange for admitting California as a free state.

Even the notion of a “popular sovereignty” vote in favor of slavery is dismissed in Seward’s “higher law” formulation.

Which leaves Wilmot’s flat-out ban on slavery in the west as Seward’s only answer. In effect, this speech on March 11 signals the death knell for the bill that Clay has put forward. It’s now up to the various sides to search for a new solution.