Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 202: The Nation Is Shocked By A Brutal Assault In The Senate On Charles Sumner

1811-1856

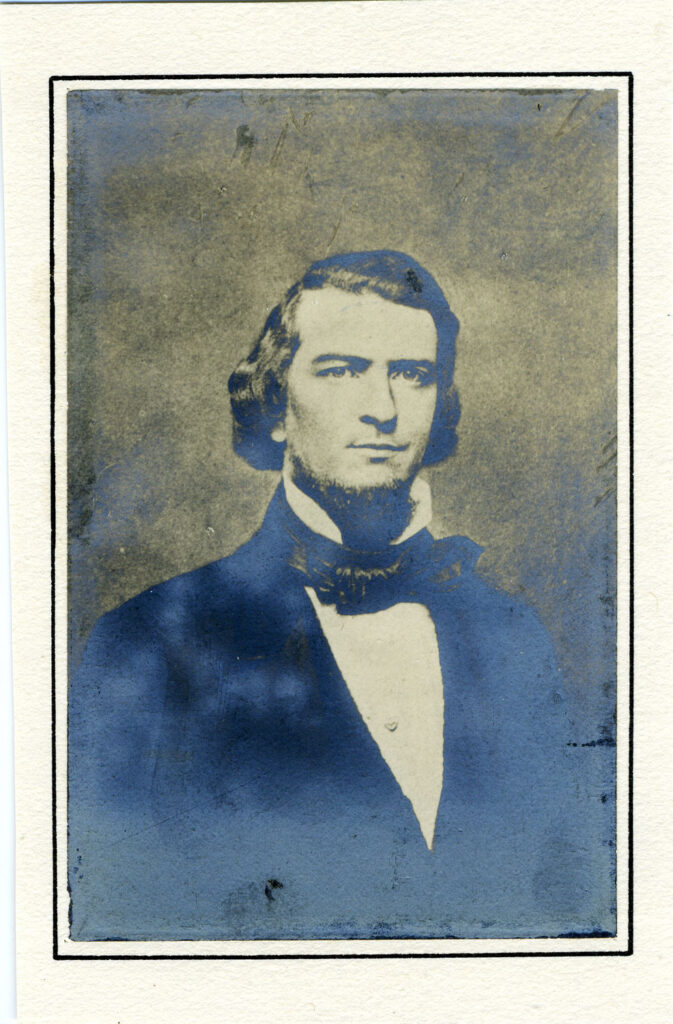

Charles Sumner: Personal Profile

While most members of Congress are content to delay action until the report from the “Kansas Investigation Committee” becomes available in June 1856, one Senator is dead set on provoking his “Slave Power” colleagues, particularly Stephen Douglas and a housemates of his in D.C., Andrew Butler of South Carolina.

That Senator is Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and he is fully primed in advance to lay into all who would allow slavery to spread to the west. In a note to his abolitionist colleague, Governor Salmon Chase of Ohio, he anticipates the upcoming moment:

I have the floor for next Monday on Kansas and I shall make the most thorough & complete speech of my life. My soul is rung by this outrage & I shall pour it forth.

“Pouring forth” in superior fashion on his moral certainties is a trait Sumner perfects early on in his life.

He is born in Boston on January 6, 1811, to parents who work their way from scarcity into the middle class. His father becomes a Harvard-educated lawyer, and a man well known in the city for his “causes.” These consistently push the everyday norms, calling for abolition, racial integration of schools and even inter-racial marriage.

Sumner is the oldest of nine children and, as such, is evidently expected to set the standard for moral rectitude for his siblings. Along with this comes an air of superiority that distances him from his schoolmates, and that persists throughout his life. He responds by retreating into scholarship, intent on winning admiration through the power of his mind, if not a winning personality.

He graduates from Harvard College in 1830 and from its law school in 1834. Two men appear to have a special impact on shaping Sumner’s future. One is Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Joseph Story, who teaches Sumner in law school. The other is William Ellery Channing, who reinforces the Unitarian values he has learned while attending King’s Chapel with his parents.

A three-year tour of Europe opens Sumner’s eyes to the broader world around him, draws him into literature and the arts, and leaves lasting impressions about the apparently easy assimilation of blacks in France. When he returns to the states in 1840, he is eager to begin his own career. It consists early on of a shaky law practice, lecturing at Harvard, and various editing endeavors. But Sumner is also gaining notice among Boston’s cultural elite, including fellow lecturer and budding author, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Emerson, Hawthorne, and the abolitionists, poets James Russell Lowell and Wendell Phillips.

His future trajectory changes on July 4, 1845 in a lecture he delivers in Boston titled “The True Grandeur of Nations,” which calls upon his audience to fulfill duties to current society consistent with those of the Founders.

Honor to the memory of our Fathers ! May the turf lie gently on their sacred graves ! Not in words only, but in deeds also, let us testify our reverence for their name. Let us imitate what in them was lofty, pure, and good ; let us from them learn to bear hardship and privation. Let us, who now reap in strength what they sowed in weakness, study to enhance the inheritance we have received. To do this, we must not fold our hands in slumber, nor abide content with the Past. To each generation is committed its peculiar task ; nor does the heart, which responds to the call of duty, find respite except in the world to come.

In this same speech, Sumner, a confirmed supporter of Henry Clay and the Whigs, criticizes the March 1845 Texas Annexation and warns against war with Mexico. Henceforth he is a public figure, a sought-after lecturer, and an agitator for reforming the Boston Prison System, making change to public schools proposed by his friend, Horace Mann, and totally abolishing slavery.

In 1846 when the Massachusetts’ Whigs divide along “Cotton vs. Conscience” lines, Sumner’s name is put forward to challenge his Harvard classmate and friend, Robert Winthrop, for a seat in congress, but he declines. He fears that even the anti-slavery politicians will fail to fight hard enough for the principle of Truth:

Loyalty to principle is higher than loyalty to party. The first is a heavenly sentiment, from God, the other is a device of this world. Far above any flickering battle-lantern of Party is the everlasting sun of Truth.

In 1848, Sumner helps Chase and others in founding the new Free Soil Party, an awkward coalition of those who wish to stop the expansion of slavery on moral grounds with those whose aims are self-serving on behalf of white settlers and white labor.

Although he has never run for public office, Sumner is chosen in 1850 by the Free Soilers to run for U.S. Senator against the Whig, Robert Winthrop. The state Senate gives him a needed majority of 23-14 on the first ballot, but the House takes 93 days and 26 ballots to finally go along with the choice. The opposition includes the “doughface,” Caleb Cushing, who characterizes Sumner as…

A one-idea abolition agitator …a death stab to the honor and welfare of the Commonwealth…and a disaster to the Union

Once in office, Sumner’s sanctimonious lecturing and arrogant style become well known in congress, and are off-putting to many members across party lines. Abraham Lincoln’s later capsulation seems to fit well:

I never had much to do with bishops where I live, but, do you know, Sumner is my idea of a bishop.

When he rises to address no one doubts his intentions to lay into the Slave Power and its accomplices for what he titles “The Crime In Kansas.”

May 19-20, 1856

Charles Sumner Delivers His “Crime Against Kansas” Speech

Sumner’s May 19-20 address becomes famous not for the arguments he makes about Kansas, but rather for the fury of his personal attacks on fellow senators, and the retribution which follows.

The speech begins by calling upon President Pierce to redress the “crimes” to date in the territory.

MR. PRESIDENT:– You are now called to redress a great transgression…the crimes against Kansas…where the very shrines of popular institutions, have been desecrated; where the ballot box, has been plundered; and where the cry “I am an American citizen” has been interposed in vain against outrage of every kind, even upon life itself.

This general indictment is followed, however, by a sustained ad hominin attack on the character of two senators present in the chamber, whom he calls out by name. They are Senators Andrew Butler of South Carolina and Stephen Douglas of Illinois, co-authors of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Sumner mocks the pair as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, two characters dedicated to defending the virtue of their beloved Princess Dulcinea in Cervantes’ 17th century novel. In this case, Butler is cast as the Don, whose beloved is “the harlot, slavery,” and who is surrounded by the “fanatics…who sell little children at the auction block.”

But, before entering upon the argument, I must say something of a general character, particularly in response to what has fallen from senators who have raised themselves to eminence on this floor in championship of human wrongs. I mean the senator from South Carolina, Mr. BUTLER, and the senator from Illinois, Mr. DOUGLAS, who, though unlike as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza…have chosen a mistress to whom each has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to them; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in their sight — I mean the harlot, slavery.

And if the slave States cannot enjoy what in mockery of the great fathers of the Republic, he misnames equality under the Constitution — in other words, the full power in the national Territories to compel fellow men to unpaid toil, to separate husband and wife, and to sell little children at the auction block — then, sir, the chivalric senator will conduct the State of South Carolina out of the Union! Heroic knight! A Second Moses come for a second exodus!

But not content with this poor menace, which we have been twice told was “measured,” the senator, in the unrestrained chivalry of his nature, has undertaken to apply opprobrious words to those who differ from him on this floor. He calls them “sectional and fanatical.”

For myself, I care little for names; but since the question has been raised here, I affirm that the Republican party of the Union is in no just sense sectional, but, more than any other party, national; and that it now goes forth to dislodge from the high places of the government the tyrannical sectionalism of which the senator from South Carolina is one of the maddest zealots. If the senator wishes to see fanatics, let him look around among his own associates; let him look at himself.

Then there is Douglas, “the squire of slavery,” a “madman” setting fire to the “temple of constitutional liberty.”

As the senator from South Carolina is the Don Quixote, the senator from Illinois, Mr. DOUGLAS, is the squire of slavery, its very Sancho Panza, ready to do all its humiliating offices. Standing on this floor, the senator issued his rescript, requiring submission to the usurped power of Kansas. He may convulse this country with civil feud. Like the ancient madman, he may set fire to this temple of constitutional liberty, but he cannot enforce obedience to that tyrannical usurpation.

The senator dreams that he can subdue the North. He disclaims the open threat, but his conduct still implies it. How little that senator knows himself, or the strength of the cause which he persecutes! He is but a mortal man; against him is an immortal principle. With finite power he wrestles with the infinite, and he must fall. Against him are stronger battalions than any marshaled by mortal man — the inborn, ineradicable, invincible sentiments of the human heart; against him is nature in all her subtle forces; against him is God. Let him try to subdue these.

Sumner finally turns his guns on the root cause of the turmoil in Kansas — the 1854 Kansas Nebraska Act, a “swindle” perpetrated under the guise of the “popular sovereignty” doctrine.

After thirty- three years, this (1820) compromise — in violation of every obligation of honor, compact, and good neighborhood — itself a landmark of Freedom, was overturned, and the vast region now known as Kansas and Nebraska was opened to slavery, under the guise of popular sovereignty. Sir, the Nebraska bill was in every respect a swindle.

Here were smooth words — to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way –such as belong to a cunning tongue enlisted in a bad cause. By their effect, the congressional prohibition of slavery, which had always been regarded as a seven-fold shield, covering the whole Louisiana Territory north of 36 deg. 30′, was now removed, while a principle was declared, which would render the supplementary prohibition of slavery in Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington, “inoperative and void,” and thus open to slavery all these vast regions, now the rude cradles of mighty states.

Once the Kansas-Nebraska Act was in place, southern forces, joined by President Pierce, “by whose complicity the prohibition of slavery had been overthrown,” focused on making Kansas into a Slave State.

The bare- faced scheme was soon whispered that Kansas must be slave State. Secret societies were organized in Missouri ostensibly to protect her institutions; It was confidently anticipated, that, by the activity of these societies, and the interest of slaveholders everywhere, with the advantage derived from the neighborhood of Missouri, and the influence of the Territorial government, slavery might be introduced into Kansas, quietly but surely.

But the conspiracy was unexpectedly balked. The debate, which convulsed Congress, had stirred the whole country. The populous North, stung by a sharp sense of outrage, and inspired by a noble cause, poured into the debatable land, and promised soon to establish a supremacy of numbers there, involving, of course, a just supremacy of freedom.

When anti-slavery northerners flocked in to turn the popular sovereignty tide, the southern cabal launched the “crime against Kansas,” led by Senator David Atchison of Missouri.

Then was conceived the consummation of the crime against Kansas. What could not be accomplished peaceably was to be accomplished forcibly. In the foreground all will recognise a familiar character, in himself a connecting link between the President and the border ruffian — who sat in the seat where once sat John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, David R. Atchison.

The violence, for some time threatened, broke forth on the 29th November, 1854, at the first election of a delegate to Congress, when companies from Missouri, amounting to upwards of one thousand, crossed into Kansas, and, with force and arms, proceeded to vote for Mr. Whitfield, the candidate of slavery. The election of a member of Congress recurred on the 2d October, 1855, and the same foreigners came from Missouri, and once more forcibly exercised the electoral franchise in Kansas. Five times and more have these invaders entered Kansas in armed array, and thus five several times and more have they trampled upon the organic law of the Territory.

Here is complete admission of the Usurpation, by the Intelligencer, a leading paper of St. Louis, Missouri, made in the ensuing summer: “Atchison and Stringfellow, with their Missouri followers, overwhelmed the settlers in Kansas, browbeat and bullied them, and took the Government from their hands.” Sir, all this was done in the name of Popular Sovereignty.

Sumner’s rhetoric reaches a low point when his fury gets out of hand after being interrupted thirty-five times by Senator Butler — who suffers from a recent stroke causing a slurring of his words. This prompts Sumner to mock him for his “incoherent phrases and loose expectoration of speech.”

With regret, I come again upon Mr. Butler, who overflowed with rage at the simple suggestion that Kansas had applied for admission as a State; and, with incoherent phrases discharged the loose expectoration of his speech, now upon her representative, and then upon her people.

And yet another, with all the prejudices of the senator from South Carolina, but without his generous impulses, who on account of his character and rancor deserves to be named. I mean the senator from Virginia, Mr. Mason, who, as author of the fugitive slave bill, has associated himself with a special act of humanity and tyranny.

After almost three hours, Sumner closes, again railing against The Slave Power and calling for the admission of Kansas as a free state.

Among these hostile senators, Kansas bravely stands forth. In calmly meeting and adopting a frame of Government, her people have with intuitive promptitude performed the duties of freemen; and when I consider the difficulties by which she was beset, I find dignity in her attitude.

In offering herself for admission into the Union as a FREE STATE, she presents a single issue for the people to decide.

And since the Slave Power now stakes on this issue all its ill-gotten supremacy, the People, while vindicating Kansas, will at the same time overthrow this Tyranny.

Many in the audience are dismayed by the obvious breech of parliamentary courtesy displayed by Sumner. Among them is Stephen Douglas, who is reported to have said during the talk “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool.”

May 22, 1856

Congressman Preston Brooks Canes Sumner On The Senate Floor

Two days after Sumner’s speech, Douglas’s comments prove prophetic.

Many southerners are outraged by the remarks, among them thirty six year old Preston Brooks of South Carolina, currently serving a second term in the U.S. House.

Brooks’ reputation as a hot-head is well established at the time. In November 1840 he engages in an ongoing quarrel with another Fire Eater, Louis T. Wigfall. This begins with fisticuffs, extends to a gunfight which kills Thomas Bird, a friend of Brooks, and climaxes in a costly duel along the Savannah River. Wigfall takes a bullet in the thigh, while Brooks is shot in the hip, a wound which causes a life-long limp and a walking cane for support.

When Brooks learns of the attack on Andrew Butler, his second cousin, his immediate response is to challenge Charles Sumner to a duel — but he is dissuaded by his South Carolina colleague, Congressman Laurence Keitt, who argues that only gentlemen fight duels, and Sumner is no gentleman.

So Preston settles on a public beating instead, to be administered with his walking stick, a stout gutta percha weapon crowned with a golden head.

On the afternoon of May 22, Brooks, Keitt and congressman Henry Edmundson enter a nearly empty Senate chamber and approach Sumner, who is sitting at his desk writing letters. Brooks informs him that his speech has libeled his kinsmen, Butler, and, as Sumner tries to rise, he begins to beat him violently with his cane.

I…gave him about 30 first rate stripes. Toward the last he bellowed like a calf. I wore my cane out completely, but saved the head which is gold.

At six foot four inches tall, the Senator finds his legs trapped under his desk, which is bolted to the floor. In a frenzy to escape, he rips the bolts out in rising, with his head bleeding profusely. With Brooks still flailing away, he finally reels convulsively up the aisle and into the arms of New York congressman Edward B. Morgan, who helps him to a chair, where he loses consciousness.

When the commotion draws others to the scene, Keitt brandishes a pistol to keep them from interfering.

Another New Yorker, Ambrose Murray, seizes Brooks’s arm, and Senator John J. Crittenden shouts out “don’t kill him.” Robert Toombs appears and restrains Keitt from striking Crittenden. Douglas becomes aware of the turmoil, but decides to stay out of the middle.

As Brooks is led away, Sumner is slumped in another senate chair with his feet protruding into the center aisle. He gradually comes around, and a page brings him a glass of water, before he is helped to an anteroom, where a doctor is called to put stitches into his wounds. His shirt collar is soaked in blood, as is his suit jacket. When the work is completed, Senator Henry Wilson helps him to a carriage and takes him home to bed.

May – June 1856

Reactions To Brooks’ Assault Differ Sharply In The North Versus The South

Word of Brooks’ assault becomes national news overnight, and the coverage reflects the growing antagonism between the North and the South.

William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the New York Evening Post, characterizes Sumner as another martyr to the Slave Power:

The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and would stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder. Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them?

Ralph Waldo Emerson writes:

I do not see how a barbarous community and a civilized community can constitute one state. I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom.

Hundreds of letters are sent to Sumner, some expressing sympathy for his martyrdom, others expressing intense anger toward the South and vowing revenge. Public protest meeting take place across the North, including some 5,000 people who show up on May 24 for a rally at Faneuil Hall.

Brooks on the other hand is hailed as a hero across the South, for “lashing the Senate’s vulgar abolitionists into submission.” Scores of citizens respond by sending him “replacement canes” to continue his good work.

Nevertheless, he is arrested for assault, then quickly released on $500 bail.

When it appears that no other action will be taken, Senator Seward asks that a committee be assembled to study the incident. Six days after the attack, on May 28, 1856, a brief report is issued. It reflects the lukewarm personal feelings toward Sumner among many of his fellow senators, and brushes off the incident saying it was:

A breach of the privileges of the Senate…(but) can only be punished by the House of Representatives.

In the House a separate group is formed, taking testimony from twenty-seven witnesses, including Sumner himself. It reports its findings on June 2, 1856, which include a call for Brooks to be expelled and both Keitt and Edmundson to be censured.

After bitter debate and threats of more duels, a vote will finally be taken on the recommendations on July 14, 1856. While members vote to expel Brooks by a margin of 121 to 95, this falls short of the two-thirds majority needed to act. The regional split is alarming, as every Southern representative votes against the measure. Meanwhile, Keitt is censured for his involvement and Edmundson is acquitted.

Brooks responds by resigning from the House after paying a $300 fine. His constituents, however, refuse to accept his act, and immediately vote him back into office. He returns to the House, before dying suddenly in January 1857 after a bout of the croup.

Sidebar: Conflict Over The Extent Of Sumner’s Injuries

Subsequent to the caning attack, Charles Sumner will disappear from the Senate for well over three years, not returning to full-time duty until December, 1859.

The South pounces on his absence as a sign of his personal shame over the rhetoric in his speech, and of his moral cowardice for hiding from his critics. They claim that his wounds were exaggerated all along and that he intentionally blew them out of proportion to enhance his political standing in the North.

The truth seems to differ. Clearly Sumner is in terrible shape immediately after being assaulted. He has lost consciousness and the gashes to his head require stitches. He does appear to bounce back after the first few days, but then relapses, with his wounds emitting pus, a temperature over 100, a high pulse rate, and significant pain reported.

After two weeks his wounds are healing, but other symptoms appear. He has difficulty rising from a chair and needs a cane to steady his stride. Those who know him well say that his natural energy is depleted and that he is often prone for days on end. His secretary writes as follows:

At times he feels as though the blows were raining upon his head again; then will feel a numbness in the scalp; then again acute pains; then a sense of exhaustion that presents any physical or mental effort.

His doctor concludes:

From the time of the assault to the present, Mr. Sumner has not been in a situation to expose himself to mental or bodily excitement without the risk of losing his life.

After the passage of time, he is able to voyage to Europe in the Spring of 1857 and again in 1858, both trips drawing sneers from those who doubt the extent and duration of his injuries.

In the end, however, it seems apparent that the effects of the attack he suffered have had a lasting effect on his physical and psychic health. A modern prognosis would likely classify his long-term afflictions as post-traumatic stress syndrome.