Section #16 - Open warfare in “Bloody Kansas” follows fraudulent election wins for Pro-Slave State forces

Chapter 187: The “Ostend Manifesto” To Seize Cuba Embarrasses Pierce’s Administration

From the moment Pierce is sworn in, he feels pressure from the southern wing of his party to satisfy their economic needs by expanding the borders for slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Bill opens this possibility within existing U.S. territory, but this is hardly a certainty. Hence the administration’s gaze turns to acquiring new land, with the island of Cuba once again front and center.

America’s fixation on the lucrative sugar plantations of Cuba traces back to Jefferson, who declares it “the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States.”

By the 1840’s the island nation has become the world’s leading producer of sugar, supplying some 30% of total global demand. Polk’s $100 million offer to buy it is rejected by Spain in 1848, and filibustering efforts of Narciso Lopez end with his public execution in 1851.

The drumbeats resume in February of 1854 after an over-eager Spanish harbor impounds the cargo on the Black Warrior, a ship making its traditional run between Cuba and New York City. This act is seized upon by Pierre Soule, the Louisiana man serving as Pierce’s Minister to Spain, to rattle retaliatory sabers in the halls of Congress.

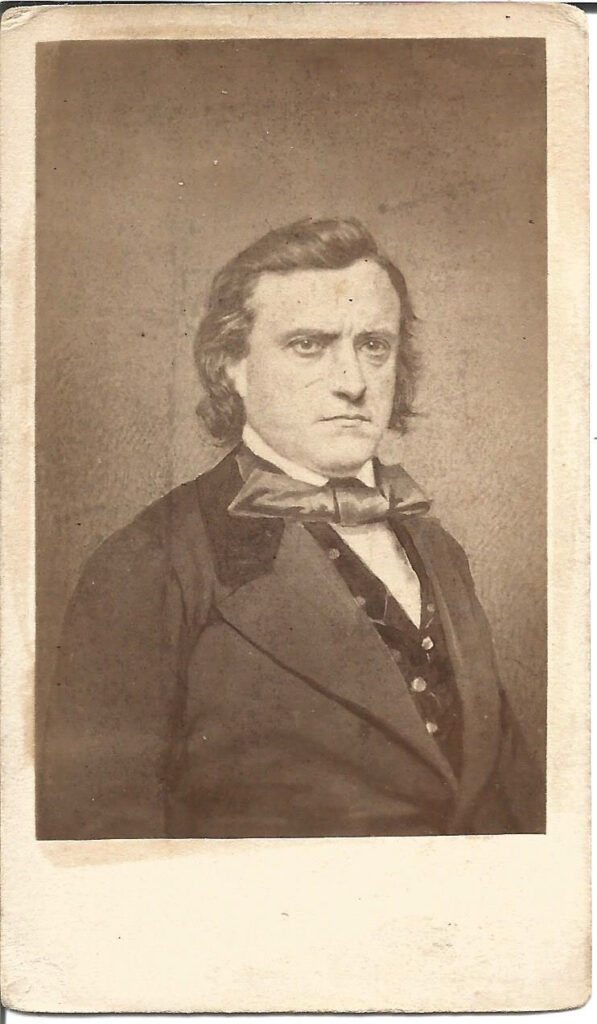

In turn, Secretary of State William Marcy tasks his three key European ambassadors with proposing a plan to deal with Cuba and Spain. Soule is joined in this effort by James Buchanan, serving in the UK, and John Mason, stationed in France. They meet for three days in Ostend, Belgium, a coastal town fronting the Mediterranean in Flanders.

Their discussions lead to a dispatch sent from Aix-la-Chapelle to Washington on October 15, 1854 which becomes known as the “Ostend Manifesto.”

October 15, 1854

The “Ostend Manifesto” Posits The Use Of Force To Seize The Island

The manifesto sent to Pierce begins by recommending the purchase of Cuba, for the good of Spain and the U.S.

Sir: The undersigned… have arrived at the conclusion, and are thoroughly convinced, that an immediate and earnest effort ought to be made by the government of the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain at any price for which it can be obtained, not exceeding the sum of $ (unstated)…(This) transaction will prove equally honorable to both nations.

This is followed by various rationales, ranging from the self-serving to the downright cynical. The first argues that Cuba “belongs naturally” to America by dint of its geographical proximity:

Its geographical position…(makes) Cuba as necessary to the North American republic as any of its present members…it belongs naturally to that great family of states of which the Union is the providential nursery.

Next comes sheer hypocrisy, with Mason – who drafted the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act – being joined by Soule and Buchanan in decrying the on-going African slave trading present on the island:

As long as (the current) system endures, humanity may in vain demand the suppression of the African slave-trade in the island. This is rendered impossible whilst that infamous traffic remains an irresistible temptation and a source of immense profit to needy and avaricious officials, who…scruple not to trample the most sacred principles under foot.

Left alone, Cuba may become “exceedingly dangerous” – since a black insurrection there could encourage slave uprisings in America.

Considerations exist which render delay in the acquisition of the island exceedingly dangerous to the United States. The system of immigration…and the tyranny and oppression which characterize its immediate rulers, threaten an insurrection at every moment which may result in direful consequences to the American people.

Should another black leader like Toussaint Louverture arise, Spain would lose not only their island, but also the money America is willing to pay for it.

It is not improbable, therefore, that Cuba may be wrested from Spain by a successful revolution; and, in that event, she will lose both the island and the price we are willing now to pay for it-a price far beyond what was ever paid by one people to another for any province.

The three statesmen then ask what America should do if Spain refuses to sell.

After we shall have offered Spain a price for Cuba far beyond its present value, and this shall have been refused, it will then be time to consider the question; does Cuba, in the possession of Spain, seriously endanger our internal peace and the existence of our cherished Union?

Their answer, stated boldly, is to “wrest it from Spain” by force!

Should this question be answered in the affirmative, then, by every law, human and divine, we shall be justified in wresting it from Spain, if we possess the power; and this upon the very same principle that would justify an individual in tearing down the burning house of his neighbor if there were no other means of preventing the flames from destroying his own home.

To do any less, they say, would be to expose the white race to “horrors,” and “commit base treason…endangering the fair fabric of our Union.”

We should, however, be recreant to our duty, be unworthy of our gallant forefathers, and commit base treason against our posterity, should we permit Cuba to be Africanized and become a second St. Domingo, with all its attendant horrors to the white race, and suffer the flames to extend to our own neighboring shores, seriously endanger(ing)…the fair fabric of our Union. We fear that the course and current of events are rapidly tending toward such a catastrophe. We, however, hope for the best, though we ought certainly to be prepared for the worst.

On top of the threat posed by an “Africanized Cuba,” the recent “flagrant outrage” committed in Cuba by Spanish officials (i.e. the Black Warrior cargo seizure) “would justify a resort to measures of war in vindication of national honor.”

A long series of injuries to our people have been committed in Cuba by Spanish officials, and are unredressed. But recently a most flagrant outrage on the rights of American citizens and on the flag of the United States was perpetrated in the harbor of Havana under circumstances which, without immediate redress, would have justified a resort to measures of war in vindication of national honor. That outrage is not only unatoned, but the Spanish government has deliberately sanctioned the acts of its subordinates and assumed the responsibility attaching to them.

In the end, the only sensible course of action lies in “the cession of Cuba to the United States.”

This course cannot, with due regard to their own dignity as an independent nation, continue; and our recommendations, now submitted, are dictated by the firm belief that the cession of Cuba to the United States, with stipulations as beneficial to Spain as those suggested, is the only effective mode of settling all past differences, and of the securing the two countries against future collisions. We have already witnessed the happy results for both countries which followed a similar arrangement in regard to Florida.

March 3, 1855

Northerners In Congress Resist The Manifesto As Work Of The “Slave Power”

The Ostend Manifesto lands on Pierce’s desk in November 1854 amidst the early Northern resistance to the Kansas-Nebraska Bill passed six months earlier, and initial warning signs that the Democrats might be in danger of experiencing sizable losses in upcoming elections.

The President fears that any hint of a U.S. plan to take Cuba by force will be judged as one more capitulation on his part to the whims of the “Slave Power.” His efforts to keep the dispatch secret include failing to mention it in his annual December address to Congress.

But the contents soon appear in public, with a near perfect reprise in the powerful New York Herald, run by its pro-Know Nothing publisher, James Gordon Bennett.

Contributing to the leaks is none other than Pierce’s own Spanish Ambassador, Pierre Soule, who openly touts the policy in search of garnering support.

Angry Northern Congressman demand disclosure of the full document, and this occurs on March 3, 1855.

The abolitionist editor of The New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, labels it the “Manifesto of Brigands,” the work of Southern planters and their lackey “doughface” Northern politicians to steal more land for slavery.

The criticism plays out from there. Foreign ministers in Madrid, Paris and London denounce the threat of force, and an embarrassed Pierce instructs Soule to end his negotiations, which leads to his immediate resignation.

The Ostend Manifesto will prove to be no more than an historical footnote, but at the time is amplifies the rift between the South and the North, including within the Democratic Party, and further erodes any possibility of a second term for Franklin Pierce.