Section #1 - America’s years as a British Colony end with The Revolutionary War

Chapter 7: The Revolutionary War

August to November 1776

Washington Almost Loses His Army On Manhattan Island

In June of 1776, the British signal their absolute determination to put down the colonies’ rebellion by off-loading some 32,000 imported troops on Staten Island, eight miles below the southern tip of Manhattan.

From this moment on, Washington’s garrison of 28,000 men around Ft. George is in dire jeopardy, absent a naval force to protect either flank of his island salient. His second-in-command, Major General Charles Lee, a professional soldier, sees this immediately:

Whoever commands the sea, must command the town.

But Washington rejects Lee’s assessment, with encouragement from a Congress that just declared independence and is loath to have it commence with the loss of New York.

Howe recognizes that the fortifications on Long Island are crucial to the American defense, since they dominate both the Hudson and East Rivers surrounding Manhattan. If he can take Brooklyn Heights, he’ll transport troops up both rivers, send them inland to link up in a defensive chain, and Washington’s entire army before it can escape to the north.

On August 22 the British land on Long Island and move toward Brooklyn. The astute general Clinton leads a flanking movement which routs the American right on August 27, in the first truly sizable battle of the war. But Howe pauses just long enough to allow Washington to execute a risky nighttime evacuation, ferrying 9500 troops across the East River from Brooklyn to Ft. George. Despite this success, the Long Island battle has cost him 1,012 casualties.

But Washington has moved from one trap to another, in New York City. Once again it is only Howe’s slow pursuit that allows the Continental army to survive. Much to Clinton’s chagrin, Howe waits until September 15 to move across the river and force Washington to abandon the city.

Captain Aaron Burr engineers the escape plan, which saves both Washington and his aide, Alexander Hamilton. But when he fails to receive a promotion for this action, Burr never quite forgives these two superiors.

Howe gives chase, but Washington survives a crucial stand-up battle, nine miles north, at Harlem Heights, which provides another momentary respite.

Still Congress refuses to entirely surrender New York, and Washington makes another tactical mistake to try to save it. He divides his army in two, with his main body of 16,000 troops scurrying north another 10 miles to White Plains, and the rest staying behind to hold two Hudson River forts. Colonel Robert Magaw and his 2,800 men are left to defend Ft. Washington on the east bank of the Hudson and 3500 men under General Nathanael Greene are assigned to hold Ft. Lee on the west bank, in New Jersey.

One other man left behind is 21-year-old Captain Nathan Hale, assigned to spy on Howe’s army.

The British quickly apprehend Hale, accuse him of planning to torch the city, and hang him on September 21. His last words from the gallows, however, endure.

I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.

On October 28 Howe catches up with Washington at White Plains and a pitched battle along the Bronx River, ends with the Americans holding their own, but then abandoning the field for another retreat 15 more miles north to Peekskill.

Instead of chasing Washington’s main army, Howe turns back south to make him pay for dividing his army, by destroying it in detail.

On November 16, Howe attacks the two undermanned Hudson River forts. Magaw and his 2,800 men capitulate, and Greene just manages to escape west to Hackensack. The battle for New York is over, with 4,000 Americans lost along the way. From start to finish it has been an unmitigated disaster for the Americans.

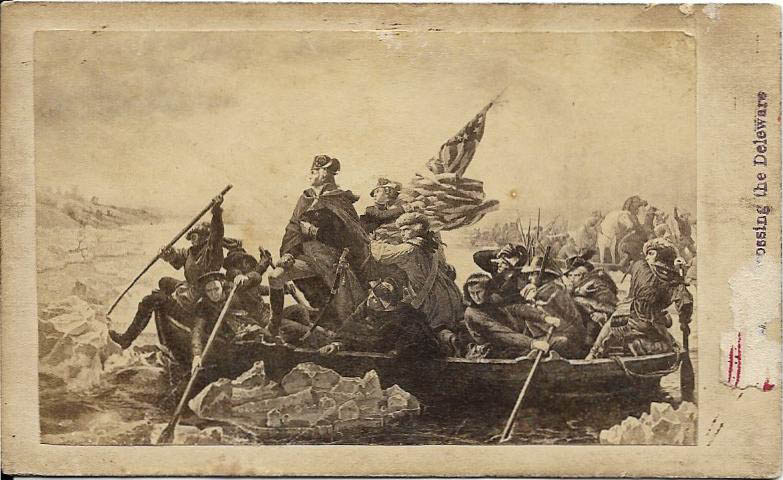

December 25, 1776

Washington Crosses The Delaware For A Much Needed Victory At Trenton

With the winter of 1776 approaching, Washington senses that the morale of his army, and his nation, is rapidly dwindling after the loss of New York. The time has come for bold strokes. Two upcoming battles – at Trenton, New Jersey and Saratoga, New York – will begin to swing the war’s momentum.

Once Washington realizes that Howe is no longer chasing him toward Peekskill, he swings his 5,000 troops west across the Hudson and then all the way south through Hackensack, Newark, Princeton, and over the Delaware River, just below Trenton. By December 8 his weary forces are camped there, facing a superior British army of 10,000 under Major General Charles Cornwallis across the river. The outlook here is ominous, until Howe decides to end the campaign for the winter. Instead of attacking Washington, Cornwallis decamps Trenton, leaving behind a small force of Hessians.

At this moment, Washington does the totally unexpected.

On Christmas Day he decides to hurl his entire army across the Delaware against the Hessian rearguard. Washington’s plan to make two feints downstream is foiled by icy river conditions, but he himself leads some 2400 men to an upriver ferry and follows up with a devastating surprise attack on the Hessian’s right flank. The result is a rout. The Hessian commander, Colonel Johann Rall, is killed, and 918 troops are forced to surrender.

Washington continues with another victory at Princeton on January 2, 1777, then decides to rest his fought-out troops and prepare for the Spring.

October 10, 1777

America’s Victory Over Burgoyne At Saratoga Stuns The World

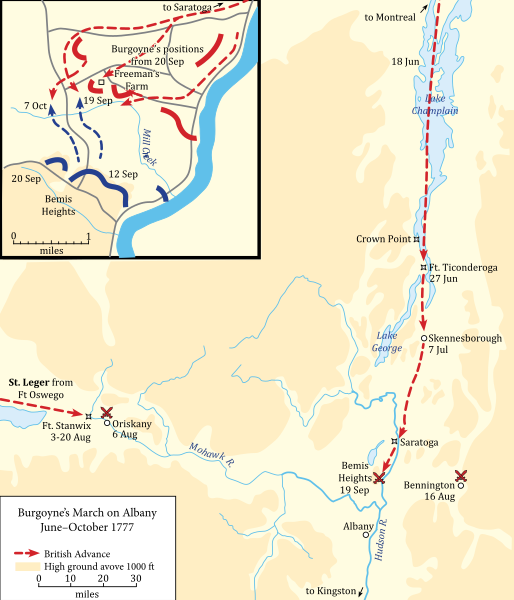

As both sides pause, it’s clear the British have become frustrated by the failure to end the rebellion in 1776 and the mounting costs associated with their efforts. General Carleton’s efforts in Canada are questioned by the crown, and his northern army command is handed over to Major General John Burgoyne — who lays out a bold plan to sail down Lake Champlain, take Ft. Ticonderoga, and then move over-land to assault Albany – thus cutting off New England from the other colonies.

On June 13, 1777, Burgoyne moves from Montreal to Lake Champlain, and sets sail with a force of 4,000 Regulars, 3,000 Hessians and 1,000 tribesmen. On July 5 he wins a major victory by forcing General Arthur St. Clair and his 2,500 troops to abandon Ft. Ticonderoga. Ten weeks of hard overland marching and skirmishing, bringing him to the town of Saratoga, some 35 miles north of his objective, Albany.

Waiting for him there is General Horatio Gates, named on August 19 to replace Schuyler, who has arrayed his 7,000 troops in a strong defensive position at Bemis Heights, south of town, along the west bank of the Hudson River.

Burgoyne decides to attack the American’s left flank, and finally moves out on September 19. But his path west takes him into a series of dense woods that first confuse and hinder the British and by mid-morning they enter a pitched battle at Freeman’s Farm, an outpost commanded by Benedict Arnold, well north of Gate’s main position. After inflicting 600 casualties, Arnold signals Gates that he will bag the entire British force if given reinforcements. The more cautious Gates declines the request, and Burgoyne’s demoralized troops retreat to lick their wounds for the day.

At this point, Burgoyne is growing desperate for a victory. He constructs two redoubts around the Freeman Farm ground and on October 7 attempts to move south from there toward Gates, But again, General Arnold turns him back, before falling with a grievous wound to his leg.

Burgoyne loses another 600 men, without even approaching the Bemis Heights position. When he flees north to Saratoga, however, Gates comes after him with his entire force. By October 10, Burgoyne is out of options, and he surrenders his remaining army to Gates.

This British capitulation at Saratoga stuns the world!

The American’s Continental army has just proven that it can go toe to toe with Britain and come out on top.

1776-1781

Sidebar: Becoming Benedict Arnold (1741-1801)

One of the great ironies related to the American victory at Saratoga involves the fate of its undeniable hero – General Benedict Arnold.

Arnold is born in Connecticut, builds a successful business as a pharmacist and book seller in New Haven, joins the militia, and later the Sons of Liberty, protesting British taxes. When the war begins, Arnold is a Captain in the Connecticut militia. But he soon proves an excellent military strategist and leader of men in the field, famous on both counts for his aggressiveness.

His two most famous battles – at Quebec City in December 1776 and Saratoga in October 1777 – end with crippling gunshot wounds to his left leg. Medical attempts at reconstruction leave it two inches shorter than his right leg, resulting in a permanent limp.

Had this second wound, at Saratoga, been fatal, Benedict Arnold would be regarded today as a military legend. But that was not to be his destiny.

Instead his path leads on to bitterness and betrayal.

In June 1778, Washington appoints him military commander of Philadelphia, the nation’s capital city. But Arnold becomes gradually dismayed by America’s prospects in the war. He marries into a family with Loyalist sympathies and makes a series of investments in the city that are seen by some as taking advantage of his position for personal gains. Arnold is outraged by the criticism:

Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet ungrateful returns.

As his disillusionment grows, he opens a secret channel of communication with Sir Henry Clinton, overall commander of British forces in America from 1778-82. His efforts are supported by his wife and by William Franklin, illegitimate son of Ben Franklin, who is a lifelong supporter of the crown.

Further inquiries into his personal conduct lead to a rebuke from his long-time supporter, George Washington, and a monetary fine for mishandling finances. This tips Arnold over to the British side and marks the beginning of treasonous disclosures about American military operations.

After resigning his post in Philadelphia, he is given command over West Point, a bastion on the Hudson that Clinton plans to attack. On August 15, 1778, Clinton offers Arnold 20,000 pounds to weaken the defenses at West Point and support a British attempt to capture it. Arnold accepts the offer on August 30, and the two begin plotting through coded messages delivered by couriers.

On September 23, one of these couriers is arrested by militiamen and the Arnold-Clinton plot is revealed to Washington. Arnold, however, manages to escape, joining British forces in Virginia as a Brigadier General, and later leading successful attacks on Richmond and around New York.

In December 1781, Arnold and his wife, granted safe passage despite her role in the plots, leave America for London – and another decade of life as a British military advisor, politician, businessman and adventurer, before dying at the age of 60.

But the name Benedict Arnold will ring down through the ages in American lore not as the hero of Saratoga as he was, but as the turncoat and traitor he became.

September 26, 1777

The British Take The American Capital Of Philadelphia

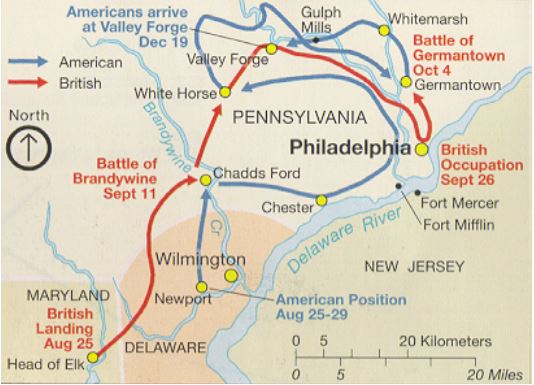

While Burgoyne moves south in Canada on July 13, General William Howe loads 13,000 troops onto 260 ships and exits New York, intent on capturing the American capital of Philadelphia.

He plans to embark in Delaware Bay, but is warned off and diverts to Chesapeake Bay, where he finally lands on August 25. From there he begins to march north through Newark and toward Philadelphia.

Washington decides to cut him off Brandywine Creek 25 miles southwest of the city, along Brandywine Creek where he entrenches.

The two armies, both numbering around 11,000 men, meet on September 11, in a battle that is a mirror image of the British win on Long Island.

Once again Howe outmaneuvers Washington, fainting at his center and executing a flanking movement which leaves the right wing of the American army vulnerable to a crushing blow.

Then Howe characteristically pauses, this time just long enough to allow Major General John Sullivan to realign his men to face the assault head on rather than from their flank. This shift doesn’t prevent a victory for Howe at Brandywine, but it does allow Washington to escape east, after suffering roughly 1,000 casualties.

Hearing of the defeat, the Continental Congress decides to vacate the capital on September 19, in favor of greater safety at York.

This move proves wise when Howe overruns American forces under “Mad” Anthony Wayne at Paoli on September 20, then crosses the Schuylkill River near Valley Forge, putting his army between Washington and Philadelphia.

On September 26, Howe marches triumphantly into the American capital.

Fighting around Philadelphia continues into the winter as Washington tries to siege the British from two forts that command the Delaware river. But Howe eventually weakens both in mid November.

Between August 1776 and September 1777, Washington has lost both New York and Philadelphia to Howe. It is indeed a low point for him as he goes into winter quarters at Valley Forge.

Winter 1777

The Continental Army Suffers And Is Transformed At Valley Forge

The winter of 1777 at Valley Forge proves to be a test of America’s willingness and ability to fight on against the British, and of Washington’s capacity to lead. As overall commander of the army, he is roundly criticized for “losing Philadelphia,” and he responds with defiance.

Whenever the public gets dissatisfied with my service…I shall quit the helm and retire to a private life.

His sense of despair, however, continues to mount. He wonders how men can survive, much less fight, when upwards of two-thirds face a winter without shoes for their feet?

Unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place…this Army must inevitably starve, dissolve, or disperse, in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can.

This is almost the case, as 2500 men perish from malnutrition, poor sanitation and disease over the next five months.

But Washington and his men at Valley Forge are eventually saved by two things – renewed financial support from Congress, and the arrival of one Baron Friedrich von Steuben on the scene.

Von Steuben is 48 years old and out of work as a staff officer in the Prussian Army under Frederick The Great when he encounters Benjamin Franklin in Paris and inquiries about service in the American army. He is hired on and sent to Valley Forge, arriving late in the winter.

Once there, he introduces the military training and iron-willed discipline characteristic of the Prussian forces.

He begins by selecting the best 100 soldiers he finds to form a “model company,” then runs them over and over through basic drills:

- The eight steps/15 motions required to fire the standard 5’6” long flintlock musket, with accuracy and with maximum speed.

- Marching formations and adjustments to maintain line integrity, respond to enemy maneuvers, and foster courage.

- The basics of camp sanitation and diet to sharply reduce illness such as dysentery and cholera.

All accomplished to bursts of profanity in German aimed at slow learners. Once this “model company” takes shape, Von Steuben than distributes his “graduates” among other units to clone the progress.

By late spring his results are self-evident. Washington’s rag-tag force now takes on a professional look and feel, and Von Steuben is named Inspector-General for the Continental Army.

February 6, 1778

France Joins The War On The Side Of America

While Washington struggles at Valley Forge, word of the major American victory at Saratoga reaches Europe in December, and prompts the French government under Louis XVI to re-think its stance on allying with the colonials.

France is still smarting in 1776 from its losses to Britain in the Seven Years War (1756-63), including the bitter defeats driving it out of Canada. So they are inclined to seek revenge

America recognizes this historical animosity and tries to leverage it from the start of the war. John Adams drafts a series of possible treaties with the French, and Benjamin Franklin tries repeatedly to sell them in Paris.

But the French balk. They do not wish to align with a losing partner, and that is exactly what the Americans look like after Washington barely escapes from Howe in New York in August 1776.

This leads to a “wait and see” attitude that prevails in France all the way to December 1777, when Gates and Burr rout Burgoyne at Saratoga.

From that moment on, diplomatic action moves along quickly, the culmination coming on February 6, 1778 at Hotel De Crillon in Paris, where two agreements are signed:

- A Treaty of Alliance, in effect a mutual defense pact, whereby the two sides agreed to take military action in response to any future attacks on either by Britain.

- A Treaty of Amity and Commerce, which confers “most favored nation” status on the two countries, for the purpose of carrying on trade. Included here is promised protection by the French navy of American ships on the high sea.

This recognition by France immediately confers global legitimacy on the Americans, in addition to materially strengthening their military resources, especially in confronting the Royal Navy.

It also greatly ups the financial ante on the British to continue the fight.

When the French ambassador informs England of the two treaties, the response is predictable and fast. On March 17, 1778, Britain declares war on France.

June 28, 1778

Drawn Battle Of Monmouth Ends Infantry Combat In The North

The French are not the only ones impressed by the American victory at Saratoga.

Three years have now passed since the April 1775 skirmish at Lexington, and British Prime Minister, Lord Frederick North, comes under increasing pressure from the Opposition Party in Parliament.

The Opposition has three complaints. The first is North’s failure to put down the American rebellion. The second is the alarming cost of the war (some 12 million pounds per year) and the tax increases required to pursue it further. And the third is the new global threats associated with France’s intervention, especially to the lucrative sugar producing islands in the British West Indies (Jamaica, Barbados, and Grenada).

In response, Britain begins to back off from its determination to crush the colonists.

The first signal of this occurs in June 1778, when King George III sends a delegation to America headed by Frederick Howard, the Earl of Carlisle, to America to offer terms by which the colonies would remain under British rule, but with representation in Parliament, and much greater control over their own affairs. The Continental Congress rejects the Carlisle Commission proposals, demanding full independence instead.

The second signal involves changes in military strategy.

Instead of concentrating its forces against the more openly rebellious Northern colonies, the decision is made to focus on the South – where public support for the crown is thought to be more widespread and intense.

If Britain can convince Loyalists in the region to fight on their behalf, a faster and cheaper end to the rebellion might materialize.

Execution of this new southern strategy begins with publicity announcing the Carlisle Commission and Britain’s willingness to welcome the colonists back into the fold, with greater self-autonomy.

This is coupled with the evacuation of Philadelphia by General Henry Clinton, who has replaced the retired General William Howe as overall commander of Britain forces.

General Clinton departs Philadelphia on June 18, 1778, hoping for an untroubled transfer of his 11,000 troops and artillery trains northeast toward Manhattan and Britain’s last impregnable stronghold in the North

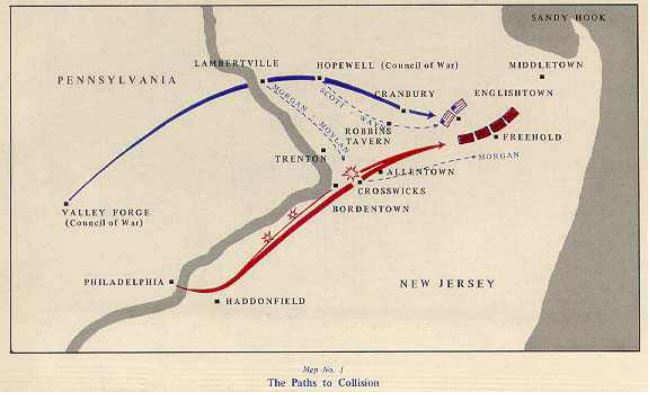

Washington, still at Valley Forge, responds quickly. He sends small bands of local militia to harass Clinton as he moves across the Pennsylvania countryside and up into New Jersey – then prepares for a general engagement around Monmouth Court House, about 40 miles below the southern tip of Staten Island, New York.

One of Washington’s generals, Charles Lee, balks at the notion of risking another major battle, when it appears the British may be in the process of giving up. But Washington will have none of that. His confidence in the Continental army is high and a win over Clinton before he reaches the safe haven of New York City could prove decisive.

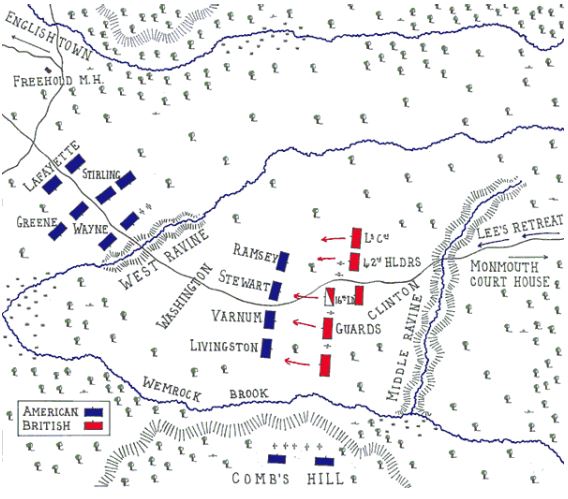

On the morning of June 28, the reluctant Lee and his 5,000 troops approach the British rearguard under the able Cornwallis, just north of Monmouth. Lee fights for several hours, but his battle plan lacks cogency and he is eventually forced to retreat.

Washington is apoplectic when he learns of Lee’s defeat and subsequently sacks him. But the battle resumes in the afternoon, another stand-up affair, with Washington in a superior defensive position able to beat back multiple assaults by the British regulars.

In the end, the battle is a draw.

Washington is unable to stop Clinton’s move to New York, but he does demonstrate the newly gained proficiency of his army.

The Battle of Monmouth represents another turning point in the war. It is the last sizable infantry clash that will take place in the North – despite the fact that the conflict drags on for another three years and the final resolution treaty is five years hence.

1779-1781

Britain’s “Southern Strategy” Succeeds Then Stalls

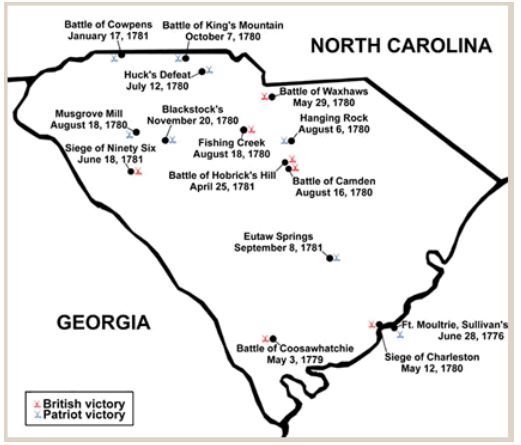

To succeed with their new efforts in the South, the British need a strong supply base similar to their position in New York City. They already hold Savannah, Georgia, after a failed American siege in the autumn of 1779. But they want a more central location, and they decide that the port city of Charleston, South Carolina, is their best bet.

On December 26, 1779, Clinton and Cornwallis leave New York harbor with 8,500 men, weaponry and supplies, for what proves to be a six week, stop-and-start voyage through winter storms, ending on February 11, 1780, just to the south of their objective.

What follows is a siege of Charleston, lasting through the Spring, and finally forcing the surrender on May 12 of General Benjamin Lincoln’s entire 5,500 man army, trapped in the city.

At this stage, Clinton turns command of his southern forces over to Cornwallis and his second in command, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarlton, who quickly earns a “no quarters” reputation on the battlefield.

After Charleston, the American’s are left with only local militia to fend off the British.

For the next two and a half years, the Revolutionary War will be fought across the South, often pitting local Loyalists against their neighbor Secessionists.

Many of the encounters take place in the interior of South Carolina. On August 16, 1780, General Horatio Gates, chosen by Congress to revitalize American troops after Charleston, blunders into a solid trouncing at Camden, South Carolina. At King’s Mountain on October 7, Cornwallis’s move toward North Carolina is turned back by frontiersmen under Colonel John Sevier.

American resistance stiffens further when Washington sends 39 year old Major General Nathanael Greene to replace Gates. On January 17, 1781, Greene’s men thrash Tarleton’s Loyalist cavalry at Cowpens, S.C. Tarleton loses 1,000 men, along with his image for invincibility. Cornwallis remains undaunted, and again pushes into North Carolina, encountering Greene on March 15, 1781, at Guilford Court House (later the town of Greensboro). At day’s end, Britain owns the field but at a disproportionately high cost of 500 casualties.

After one more draw with Greene at Hobkirk’s Hill, near Camden, South Carolina, Cornwallis decides it’s time to fight the war in Virginia, the linchpin between Washington’s northern army and Greene in the South.

The broad “Loyalist uprising” across the Carolinas and Georgia that British MP Lord North hoped for has failed to materialize, and the Americans have now proven they can stand toe to toe with the redcoats in land battles. All that England has left to show for its move South are Savannah and Charleston, both secured by their superior fleet.

But the Royal Navy is about to be tested in Virginia by America’s new ally, the French.

August-September 1791

The Three-Year Old American-French Alliance takes Hold In 1781

By the time Cornwallis completes his 240-mile trek from Wilmington, NC to Petersburg, Virginia, units under now turn-coat British General Benedict Arnold and William Phillips have burned and pillaged towns along James River and taken control of the new capital city of Richmond.

This incursion into his home state alarms Washington and he sends 5,000 troops under command of the French General Marquis de Lafayette, to defend Virginia and capture the traitor, Arnold.

Given that Cornwallis has 7,000 troops at his disposal, Lafayette decides to avoid a major battle, instead maneuvering his army along the Rapidan River toward Williamsburg. They fight a sharp skirmish there on July 6, 1781.

At this point, General Clinton, resting comfortably in Manhattan, senses that the combined 9,000-man force of Washington and the Frenchman, Comte de Rochambeau, may be readying a move against him. In response, he first orders Cornwallis to detach 3,000 men back to New York City, then changes his mind and tells him to occupy the deep water port at Yorktown, which he does.

At first, this move to Yorktown looks safe – but then two crucial factors shift the equation.

On May 22, Washington learns that French Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, plans to move his fleet from the Caribbean to America in the Fall, to support the alliance. For the first time in the war, Britain’s absolute dominance of all sea lanes will be challenged.

Then Washington settles on a major gamble, reminiscent of his desperate move across the Delaware to Trenton some five years earlier.

He leaves a shadow army of 3,000 to contain Clinton in New York, and secretly marches with Rochambeau and 6,000 men on August 21 to join Lafayette. Fortunately, Clinton does not learn of the move until September 2, when Washington’s army meets Admiral De Grasse’s fleet in Chesapeake Bay, north of Baltimore.

In addition to his navy, the Admiral brings another pleasant surprise – 2,500 French troops, who disembark to bolster the American-French infantry.

Suddenly a joint land and sea attack on Cornwallis at Yorktown becomes possible.

October 19, 1781

The World Turned Upside Down At Yorktown

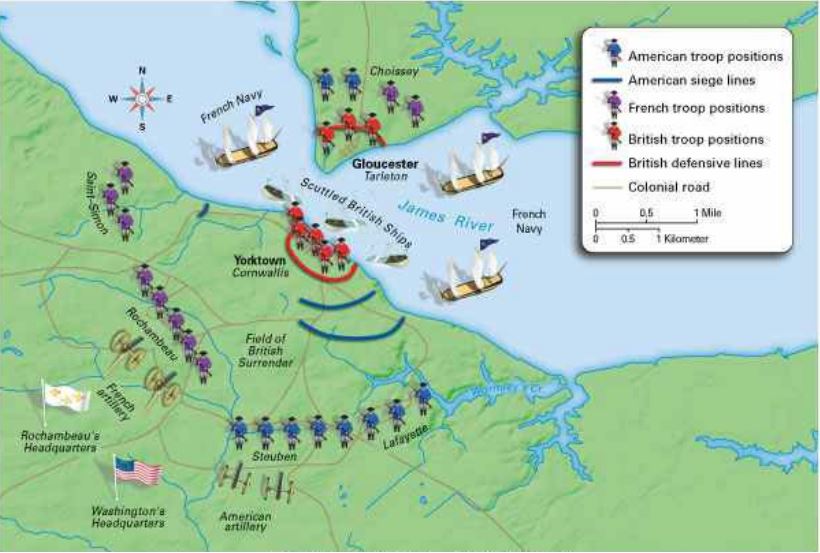

After settling on a plan of attack, Washington and Rochambeau move overland for 12 days to join up with LaFayette in Williamsburg on September 14.

In the interim, Admiral De Grasse fights a crucial sea battle with British Admirals, Sir Thomas Graves and Sir Samuel Hood, that will seal the fate for Cornwallis at Yorktown.

When DeGrasse moves north from Haiti on August 15, Graves and Hood follow him, but with only a part of the fleet, leaving the rest behind to defend the West Indies. This decision proves fateful on September 5 in the Battle of the Capes, fought for control of the entrance to James River and the Yorktown harbor.

In the early afternoon De Grasse brings his 24 warships out past Cape Henry, heading southeast and signaling the classical order “form line of battle.” The awaiting British fleet of 19 ships tacks with him, foregoes a thrust at his center, and instead opts for a broadside exchange of fire. But Hood’s rear guard never quite catches up to the French, and only eight of the Royal Navy actually close within range of DeGrasse’s main body of fifteen. This nearly 2:1 advantage in firepower results in a French victory, after two hours of intense fighting.

The two fleets continue to maneuver out of range off the capes until September 10 when de Grasse move back into the shelter of Chesapeake Bay. There he is greeted by another French squadron under Admiral de Barras, which brings his strength up to 35 ships and guarantees control of the waters surrounding Yorktown.

At this point, Cornwallis’s 7200-man army is trapped – between the French fleet on the York River and Washington’s predominantly French force of 16,500 infantry who have surrounded him by September 28 from the east and south.

When Clinton sends word promising a relief force from New York, Cornwallis abandons his outer defenses and pulls back to a more tightly controlled perimeter. In turn, Washington and Lafayette are able to construct close-in siege operations, with cannon fire taking its daily toll on the British defenders. By October 10, Cornwallis signals Clinton that his only remaining hope is a rescue by the Royal Navy. Four days later, two critical British redoubts (#9 and #10) are stormed, closing the gap between the redcoats and their assailants to only 250 yards.

September 3, 1783

The Treaty Of Paris Officially Ends The Revolutionary War

The success of the American-French alliance at Yorktown effectively signals the end of British rule over the thirteen colonies – although it takes almost two more years of sporadic warfare to drive the point home in London.

King George is willing to continue the fight, but his Parliament is not. The wartime Prime Minister, Lord North, is forced out in March of 1782.

In the spring, Ben Franklin opens unilateral talks with British counterparts, fearing that the French commitment to an ongoing alliance may be softening. He is joined over time by two other American diplomats, John Adams and John Jay.

By November 1782 a draft treaty is signed, with the opening declaration reading:

His Britannic Majesty acknowledges the said United States…to be free, sovereign and independent.

Still another ten months pass before a final agreement is concluded in Paris on September 3, 1783.

Franklin wants Britain to cede eastern Canada to reduce the odds of a future invasion, but the crown balks at the idea. Instead, the British transfer the land west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi River, to the dismay of their tribal allies.

Other articles grant fishing rights to the United States in Canadian waters and access by Britain to the Mississippi River; finalize payment of outstanding debts; arrange for the exchange of prisoners; and protect the rights of any residual Loyalists.

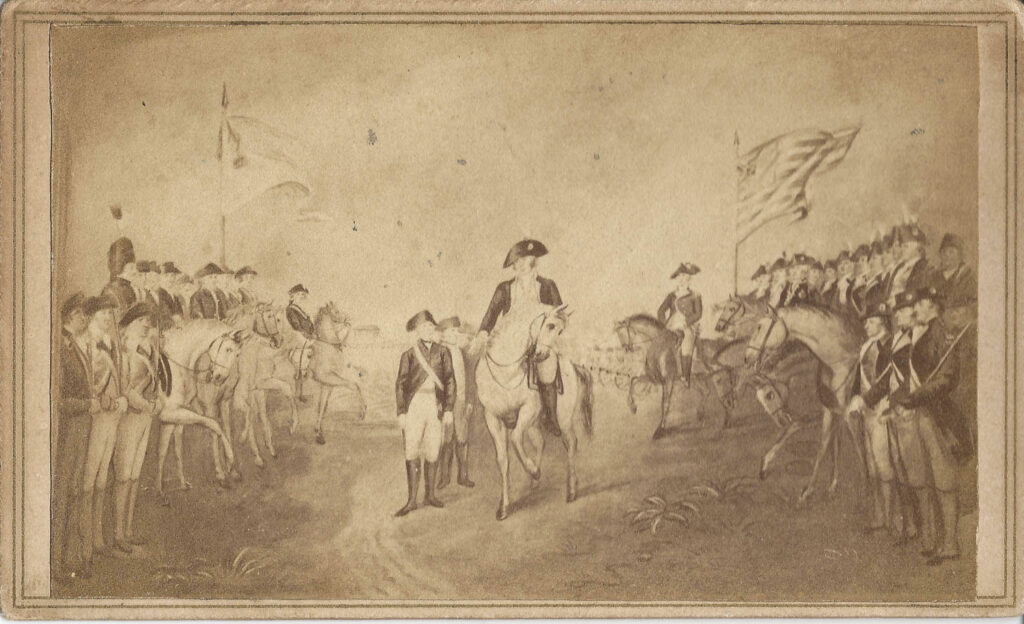

The end comes on the morning of October 19, 1781, to the beat of the long roll followed by a white flag of surrender from Cornwallis. Formal papers are signed and in the early afternoon the British army marches out of their fortifications to surrender, accompanied appropriately by a popular London tune, “The World Turned Upside Down.”

Treaty of Paris closes the first war between mostly British brethren in America.

The victory of the upstart rebels is an improbable one, and much of the credit falls to one man, General George Washington, whose leadership and sheer determination span over six years of often desperate warfare.

Before long the new nation he secured will ask him to forego private life for another call of duty.