Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 22: John Marshall’s Supreme Court Asserts Its Authority In Marbury v Madison

February 20 to March 3, 1801

Jefferson Unpacks Adams’ Court

Once in power, Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans begin to unwind the “Midnight Judges Act” of 1801 and do away with the Federalist appointments made by John Adams.

Their task is complicated by the fact that sitting judges may be removed only by impeachment involving violations of their public trust. To get around this constraint, Jefferson opts to re structure the judiciary once again. He does so in the Judiciary Act (or Repeal Act) of 1802:

- The number of Supreme Court Justices returns to its original quota of six

- The jobs of the 16 new “Federal Circuit Court Judges” added by Adams are eliminated, hence avoiding the impeachment rules.

- Each Supreme Court Justice is responsible for riding one of the six national “circuits.”

The notion of a handful of Supreme Court Justices, appointed for life and sitting in the Capitol imposing Federal guidelines over State laws and court’s decision is anathema to the Democratic Republicans. As Jefferson says:

To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy. Our judges are as honest as other men and not more so. They have with others the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps.

By revoking Adams’ changes, Jefferson feels he has once again prevented too much power from being in too few Federalist hands.

February 11 – 24, 1803

The Supreme Court Asserts Its Constitutional Authority

But the aftermath of the “Midnight Judges Act” is not yet fully “settled” by the 1802 Repeal, and it now comes back to stifle Jefferson’s efforts to limit Supreme Court power.

The roadblock is a suit filed by one William Marbury, a Maryland resident, who is an accomplished businessman, a powerful political figure in the Federalist Party, and an active campaigner against Jefferson in the 1800 election.

He comes before the Supreme Court seeking to assume a prestigious position he has been promised, as Justice of the Peace in the District of Columbia. He backs his claim with a document signed by President John Adams and “sealed” (notarized) by the Secretary of State, John Marshall, on Adams last day in office. The problem is that Jefferson refuses to honor the commission, arguing that it was not actually delivered to Marbury before Adams’ term expired.

Marbury petitions the Supreme Court to support his claim. The case is presented on February 11, 1803 and a decision is handed down quickly, on February 24. John Marshall, who was personally involved as the “notary” before becoming Chief Justice, concludes three things:

- Marbury does indeed have the right to the commission, once Adams signed it and it is notarized.

- Marbury also has the right to legal protection by a court, even in a case involving the President of the United States – a not so subtle jab at Jefferson for acting like he is above the law.

- But no, the Supreme Court cannot grant Marbury’s wish because the Constitution limits its authority to conduct “judicial reviews only to cases involving ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls…and where the state shall be a party.”

After being advised to re-file his suit within state court, and then return to the Supreme Court if he is denied, Marbury drops the protest.

However, the decision itself establishes the crucial precedent Marshall is after – the Supreme Court’s authority to overturn state and federal laws on the basis of a failure to comply with the 1787 Constitution.

This power has always been implicit in the formation of the High Court and in the “checks and balances” spirit favored by the Founders. But with Marbury, enforcement of the principle is made apparent to all.

In effect then, Jefferson wins the battle against Adams’ appointments, but loses the war against the concentration of power he now sees vested power in the Supreme Court.

He sees no evidence in the Constitution that grants six judges with lifetime appointments the power to override laws written by legislators.

The question whether the judges are invested with exclusive authority to decide on the constitutionality of a law has been heretofore a subject of consideration with me in the exercise of official duties. Certainly there is not a word in the Constitution which has given that power to them more than to the Executive or Legislative branches.

And, while Marshall draws boundaries around the types of cases the Supreme Court will hear, the Democratic-Republicans fear that it will ultimately extend its “reach.”

In this regard they are reminded that none other than James Wilson, the leading legal scholar at the Constitutional Convention and former Associate Justice under Washington, called for a Supreme Court capable of striking down any and all federal or state legislation it deemed “unjust.”

Jefferson records his concern that the Constitution may become…

A mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.

Southerners, in particular, wonder if the Marbury decision might eventually open the door for the Court to eventually “twist” the laws affecting the rights of slave owners.

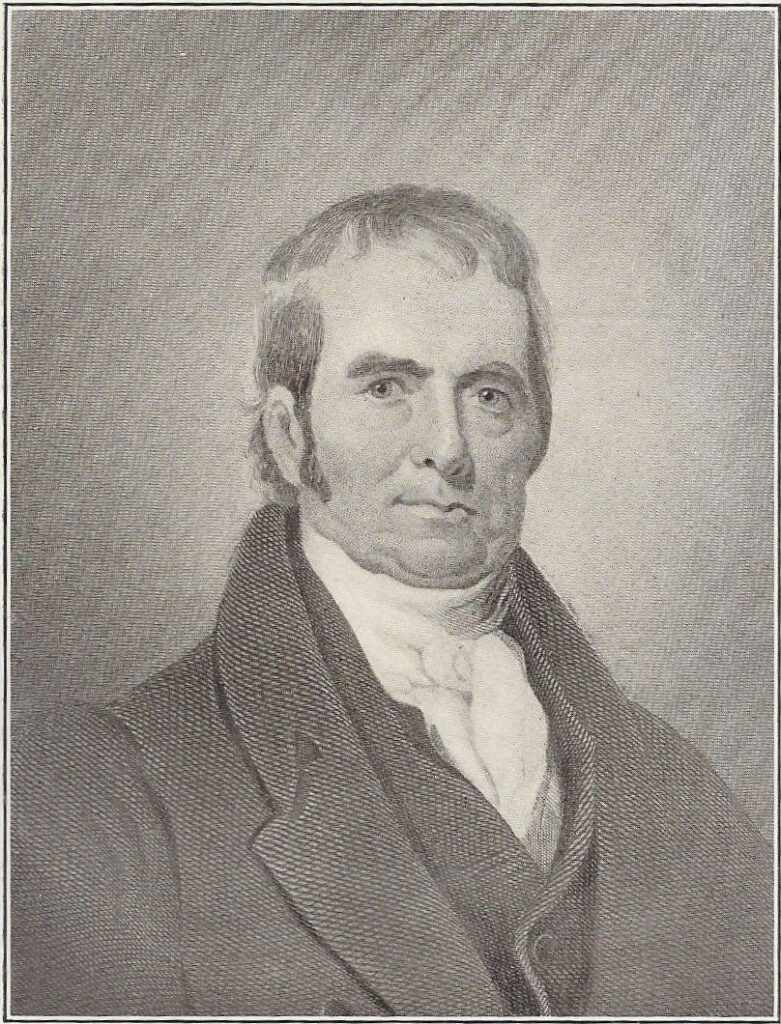

From 1803 forward, the third branch of the federal government becomes a political force to be reckoned with, especially in the hands of Chief Justice, John C. Marshall.

1801-1809

John Marshall And His Ongoing Conflicts With Thomas Jefferson

Marshall’s reprimand of Jefferson in the Marbury decision is characteristic of the personal antipathy that develops between these two intellectual giants over time.

Ironically, they are distant cousins, Jefferson’s mother being Jane Randolph, a relative of Marshall’s mother, Mary Randolph. Their fathers are both surveyors and they are both Virginians and lawyers, similarly tutored by the legendary George Wythe. There the similarities end.

Jefferson is aristocratic in his dress and bearing; distant from the common man he swears to protect. He is committed to agricultural commerce and his home state; forever suspicious that a powerful central government will evolve into an oligarchy, destructive of personal liberty and prosperity.

Marshall is forever slovenly attired and comfortable around people. He is supportive of Hamilton’s brand of capitalism and industrialization. His focus is on national rather than state affairs and he believes that a strong national government is necessary to unify, defend and build the republic.

John Marshall’s roots are considerably more humble than Jefferson’s. He has to scrape for an early education, and is drawn into the Revolutionary War at age twenty. Both Marshall and his father have distinguished military records. The son enters the War as a Lieutenant in 1775 and exits in 1779 as a Captain, after fighting at Brandywine, Monmouth and in Virginia, during Benedict Arnold’s invasion.

Some historians believe that Marshall’s disdain for Jefferson traces in part to an episode during this Virginia campaign that finds Governor Jefferson, evidently focused on securing his Monticello estate rather than joining in the actual combat against the British. The question “where is Jefferson” is asked throughout the ranks at the time.

Marshall’s war experiences also influence his political views. Camped at Valley Forge alongside his hero, George Washington, he watches the failure of the dis-organized, undisciplined and self centered “confederated states” to supply the basic support systems needed to win the war. This marks him forever as a Federalist.

After leaving the army, Marshall enrolls in a three-month course at William & Mary taught by George Wythe which features “combined theory and practice, readings and lectures, supplemented with moot courts and mock legislative sessions.” From there he is apprenticed under Wythe until his petition to join the Virginia bar is signed in 1780, ironically by Jefferson himself, who is 12 years his senior.

He opens a private practice, specializing in suits related to disputes over debts and real estate titles. His style is that of the savvy litigator, focused less on legal theory and more on practical arguments. When his efforts in court flourish, he is drawn into politics, serving in the Virginia House of Delegates off and on between 1782 and 1796. He is not yet well enough known in 1787 to attend the Constitutional Convention, but he supports its ratification in 1788, citing Federalist principles against stiff Democratic Republican opposition.

After that, he is thrust onto the national stage by John Adams, who names him Minister to France in 1797, and then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on January 31, 1801.

In the final year of Adams’ life, Adams – who previously picked George Washington to head the Continental Army — cites Marshall as his proudest act.

My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life. There is no act of my life on which I reflect with more pleasure.