Section #20 - Futile attempts to save the Union follow John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry

Chapter 245: President Buchanan Deliver His State Of The Union Address

December 19, 1859

The President Sings His Own Praises

On the day of the “Anti-Brown Rally” in NYC, James Buchanan offers up his third annual message to Congress – at a time when his presidency is collapsing around him even if he is not yet fully aware of the fact.

The speech is exceedingly long and rambling, with two- thirds of it are devoted to a litany of accomplishments he wants on the record, especially in regard to foreign policy and the nation’s finances:

- The favorable relations achieved with China, Russia, France and most other nations

- Ongoing strains with Spain, especially over the ongoing attempt to purchase Cuba;

- Yet to be fully resolved treaties with Britain regarding Central America.

- Threats from Mexico against US citizens and a proposal for military outposts in Sonora and Chihuahua.

- Support for a military force to enter Mexico should that prove necessary.

- The possible need for a show of naval force to insure safe passage in Panama and Nicaragua.

- Support for a transcontinental railroad, especially to facilitate the military defense of the west coast.

- Concern over a budget deficit of roughly $6million for fiscal year 1859-60.

- A recommendation to raise tariffs to avoid future deficits.

December 19, 1859

His Overall Views Are Delusional

One month after Harpers Ferry, Buchanan tries to tell his audience that the sectional issues have now been resolved and that the threat of a civil war is over. His words simply come across as hollow.

Due to that Almighty Power…the general health of the country has been excellent…

We have been exposed to many threatening and alarming difficulties in our progress, but…the danger to our institutions has passed away.

I shall not refer in detail to the recent sad and bloody occurrences at Harpers Ferry. Still, it is proper to observe that these events…may break out in still more dangerous outrages and terminate at last in an open war by the North to abolish slavery in the South….

For myself I entertain no such apprehension…

Questions which in their day assumed a most threatening aspect have now nearly gone from the memory of men…Such, in my opinion, will prove to be the fate of the present sectional excitement should those who wisely seek to apply the remedy continue always to confine their efforts within the pale of the Constitution.

True to his Southern tilt, he says that the remedies must be accomplished…

…Without serious danger to the personal safety of the people of fifteen members of the Confederacy.

Having just dismissed the threat, he returns to it, again referencing Harpers Ferry.

I firmly believe that the events at Harpers Ferry, by causing the people to pause and reflect upon the possible peril to their cherished institutions, will be the means under Providence of allaying the existing excitement and preventing further outbreaks of a similar character

He is then on to continued praise for the Dred Scott decision, ending the legal debate on slavery.

I cordially congratulate you upon the final settlement by the Supreme Court of the United States of the question of slavery in the Territories… protected there under the Federal Constitution.

He does so while leaving room for those Democrats still attached to the role of popular sovereignty in the process of achieving statehood.

When in the progress of events the inhabitants of any Territory shall have reached the number required to form a State, they will then proceed in a regular manner and in the exercise of the rights of popular sovereignty to form a constitution preparatory to admission into the Union.

His discussion of slavery ends with a long monologue on the history of the institution in America and a paean to the blessings it has bestowed on the Africans.

For a period of more than half a century (their) advancement in civilization has far surpassed that of any other portion of the African race. The light and the blessings of Christianity have been extended to them, and both their moral and physical condition has been greatly improved.

At present (the slave) is treated with kindness and humanity. He is well fed, well clothed, and not overworked. His condition is incomparably better than that of the coolies which modern nations of high civilization have employed as a substitute for African slaves. Both the philanthropy and the self-interest of the master have combined to produce this humane result.

Buchanan’s words here are those of men like Thomas Dew and the Reverend James Thornwell in 1832, John C. Calhoun in 1837, James Hammond in 1845, George Simms in 1852 and a host of others proclaiming that “slavery as a positive good.”

They reflect s President dedicated to one thing above all else — appeasing his Southern base in order to retain his high office.

In so doing Buchanan slays his own reputation along with his presidency.

May 1860

Sidebar: One Brief Shining Moment For Buchanan

While little goes right for James Buchanan throughout his presidency, he does get to relive his glory days as a diplomat in May 1860 when a 74 man delegation from Japan arrives at the White House to present him with the “Treaty of Peace and Amity” which has been eight years in the making.

Its origin lies with President Millard Fillmore’s commitment in 1852 to build a U.S. presence in Asia by opening up Japanese ports to facilitate coal refueling for the navy and to explore commercial opportunities.

The nation of Japan has been strictly isolated from the outside “barbarian” world since 1635 soon after the reign of the first Shogunate ruler, Tokagawa Ieyasu. This policy, administered by Samurai overseers, produces internal stability and a booming economy based on the nation’s rice, tea and silk and trade with China, Korea and the Netherlands.

Fillmore selects 58 year old Commodore William Perry, a hero of the Mexican War, to carry out the mission, using force if necessary.

Perry forms his East India Squadron and departs from Norfolk on November 24, 1852. After several stops he reaches Naha (Okinawa) on May 17, 1853 and then sails into Edo (Tokyo) Bay on July 8 over local protests.

While hoisting a white flag of peace and bringing gifts for the Emperor, Perry also points his 73 cannon toward the city and fires off blank shells, supposedly to celebrate America’s recent Independence Day. Upon landing, he presents a letter of introduction and a promise to return in 1854.

On March 8, 1854 he fulfills the promise, landing near Yokohama with ten ships and 1600 guns, and signing the “Convention of Kanagawa” which opens two ports to U.S. ships along with a consulate to advance commercial ties.

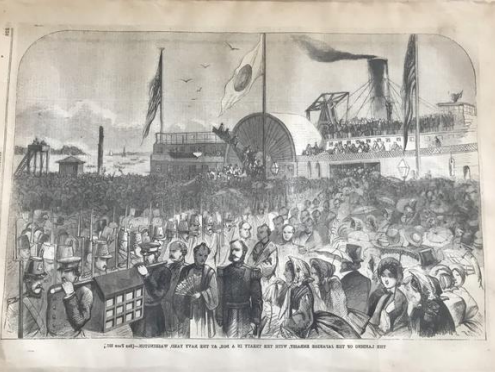

The first in-country U.S. diplomat, Townsend Harris, negotiates the final treaty and a crowd of some 5,000 people is on hand when it arrives at the Washington Navy Yard on May 14, 1860.

An elaborate gala follows three days later in the East Room of the White House, with President Buchanan as the center of attention.

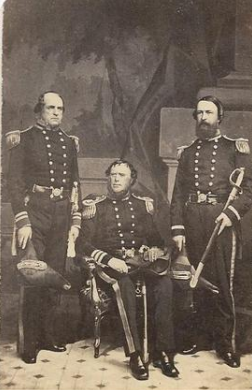

Also on hand are three Navy Commanders who paved the way for the treaty – “Smith” Lee (older brother of Robert E. Lee), Francis DuPont, and David Porter.

The actual “Harris Treaty” turns out to be a one-sided affair favoring America and eventually resented in Japan. The major commodity affected is tea, and by 1880 Japan supplies nearly half of the total U.S. consumption.