Section #13 - The 1850 Compromise has Democrats backing “popular sovereignty” voting instead of a ban

Chapter 151: More Public Violence Accompanies The Slavery Debates

April 17, 1850

Senators Henry Foote And Thomas Hart Benton Brawl In The Senate Chamber

With Clay and Douglas off searching for a new California bill, rhetorical violence on the floor of the Senate gives way to physical violence.

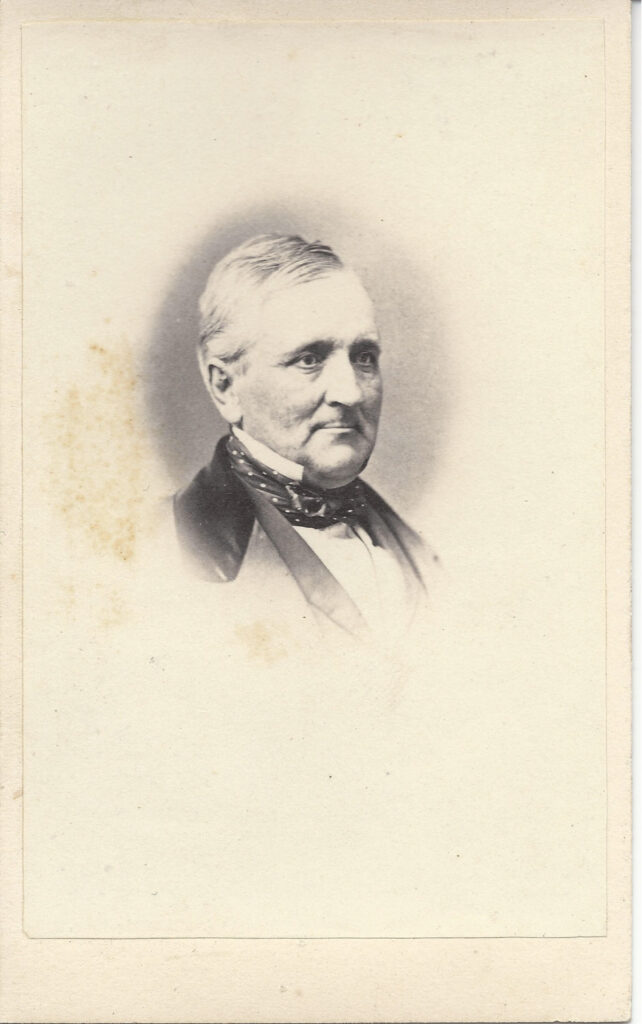

The spark occurs on April 17 after a speech by Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri who argues for immediate admission of California, without all the controversial off-sets proposed by Clay.

Benton’s position reflects his shifting attitude toward slavery. This begins in 1835 when he emancipates one of his slaves, a woman named Sarah, in return for “14 years of loyal service.” From there he progressively comes to question the impact of the institution on American society. As he says in 1849:

If there was no slavery in Missouri today, I should oppose its coming in.

For the men of the South, Benton’s position mirrors the betrayal they see with President Taylor. Two confirmed slaveholders turned their backs on the traditions and economic well-being of their region.

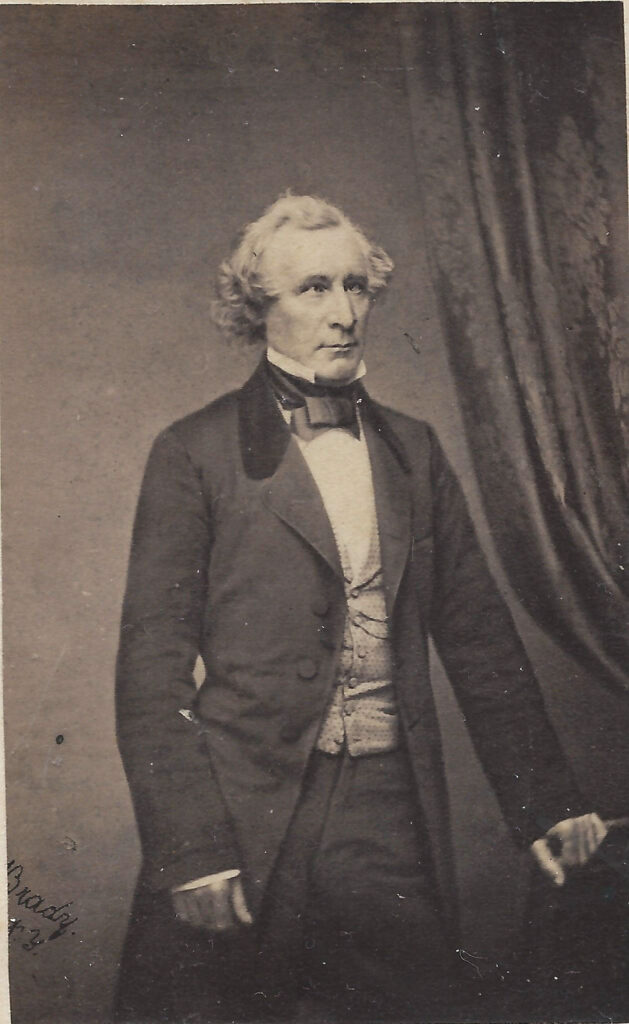

One man particularly upset by Benton is Henry Foote of Mississippi.

Foote is a relative newcomer to the Senate, but his reputation as a constant agitator is already well-established. Over the years he has fought four formal duels, being wounded himself three times. His lesser battles will include fist fights with three colleagues, Senators Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania and Solon Borland of Arkansas.

Ironically, Foote, like Benton, is a fierce Unionist. He regards every day of bickering over slavery on the floor as a threat to holding the nation together.

His limited patience with debating the issue runs out on April 17, when Benton balks at being ruled out of order by Vice President Millard Fillmore. Foote inserts himself into the dialogue, calling Benton out directly, absent the usual senatorial courtesy.

In turn, Benton rises abruptly, knocking over a tumbler on his desk and rushes toward Foote’s seat as others try to block him. Foote retreats toward the well and goes for a long rifle barreled pistol he is carrying. He cocks it and points toward Benton. Others grab the gun from Foote, but Benton sees it, opens his coat to show that he is unarmed, then roars: “let the damned assassin shoot!”

After both men are restrained and pushed back to their desks, amidst shouts for order, Vice President Fillmore adjourns the session before any further damage can be done.

This incident, however, demonstrates once again just how explosive divisions over slavery have become among the national politicians in Washington.

May 7-8, 1850

An American Anti-Slavery Society Convention Is Attacked By A White Mob

Three weeks after the Benton-Foote incident, another violent confrontation occurs in New York City, this one involving the public rather than the politicians.

The venue is the Broadway Tabernacle where the American Anti-Slavery Society is holding its annual convention. The event is well publicized in response to planned appearances by Frederick Douglass and Lloyd Garrison.

Among those displeased by this congregation of abolitionists is James Gordon Bennett, founder in 1838 of the New York Herald, which soon boasts the largest circulation in the nation. Bennett is known for his honest reporting and for a host of innovations, especially in the coverage of financial news and cultural events.

His conservative leanings, however, make him suspicious of abolitionists, as threats to the Union and to the reputation of the city.

For several days in advance of the Society event, the Herald’s editorials encourage the public to turn out to “frown down these mad people” and discourage their “dangerous assemblies.”

One who takes this literally is a Tammany operative named Isaiah “Captain” Rynders, who sets out to disrupt the convention.

On May 7, 1850, Rynders climbs on stage during Garrison’s opening address and demands to be given equal time to rebut his comments about the church’s failure to speak out against slavery. After Garrison agrees for the sake of order, Rynders sends up one “Professor Grant” whose racist harangue asserts that all negroes are “brother to the monkey.”

When Frederick Douglass rises to differ with “Grant,” Rynders says that his talents are explained by the fact that his mother was white. Douglass counters with humor, referring to Rynders as his half-brother.

A humiliated Rynders returns to the church on the second day with a mob that continues to disrupt every speaker. Wendell Phillips talk is broken by chants of “Traitor, Traitor!,” and Garrison is mocked as a religious fanatic. After members of the city police in the hall side with Rynders, the meeting is adjourned to prevent physical violence.

Bennett is satisfied with the outcome and the Herald reports:

Thus closed anti-slavery free discussion in New York for 1850.

Other coverage is more sympathetic to the event sponsors, not because of their views on slavery, but rather a shared sense that their civil liberties had been abused by the mob.