Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 90: The South’s First Cash Crops: Tobacco, Rice, Cotton And Sugar

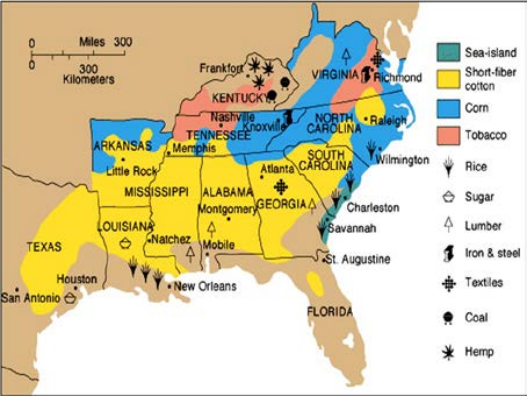

The South’s three dominant agricultural crops in the 18h century are tobacco, rice and sugar, and together they provide the foundation behind most of the aristocratic planter families of colonial America. In the 19th century they will be joined by “King Cotton.”

Tobacco

Tobacco production is concentrated early on in Virginia and parts of North Carolina, with Kentucky and Tennessee coming on later. But growing tobacco is a complex and labor intensive undertaking, from transplanting seedling into the soil to proper fertilization and then harvesting.

The tobacco leaves are heavy and dirty and, after cutting into “hands” (packets), they must be hung over five foot long poles to properly dry and cure.

Getting all of this right is not easy.

Tobacco is also an “exploitive” plant, sucking nitrogen out of the soil and depleting its capacity to replenish needed nutrients year after year. The early growers are also either ignorant of the need for crop rotations or are too eager for short-term profits to care. Thus by 1840 much of the tobacco land is played out, and the Virginia planters in particular are searching for new options to protect their fortunes. One ominous answer will lie in “breeding” slaves for sale.

Some of Virginia’s Elite Tobacco Families

| Names | Dates |

| Richard Lee | 1617-1664 |

| Robert “King” Carter | 1663-1732 |

| Benjamin Harrison III | 1673-1710 |

| William Byrd II | 1674-1744 |

| William Fairfax | 1691-1757 |

| William Beverley | 1696-1756 |

| Mann Page II | 1716-1780 |

| William Fitzhugh | 1741-1809 |

Rice

Further south, along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, the gentry is built on the production of rice, ironically using methods taught them by their African slaves. Success is predicated on the presence of swampland, fed by non-saline freshwater rivers and lakes, and temperatures that are reliably warm during the 5-6 month growing season. Preparing and managing a rice field is an arduous task, first to drain and level the swamp, then to plant seedlings in the mud, finally to carefully add back water needed to support growth and fight off weeds. Between April and September, stalks will reach about 18 inches, at which time they are cut down, left to dry in the sun for two weeks, then “flailed” to capture pods and milled to arrive at the desired rice kernels.

The entire process is fraught with risks. Inland swamps are subject to flooding after heavy rains, while coastal swamps are forever threatened by the ocean’s salt water. Losing a crop to water damage is not uncommon and severe financial losses can follow. Swampland is also the breeding ground for mosquitos and the two main killing diseases they transmit – malaria and yellow fever. Still, the mega-rice planters, scions like Joshua Ward at “Brookgreen” and William Aiken, Jr. on Jehossee Island, thrive in 1840, while searching westward toward swampland in Louisiana for the chance to expand.

Some Of Carolina’s Elite Rice Families

| Names | Dates |

| Joseph Blake | 1663-1700 |

| Arthur Middleton | 1742-1787 |

| Nathaniel Heyward | 1766-1851 |

| Joseph Alston | 1779-1816 |

| William Aiken, Sr. | 1779-1831 |

| Joshua Ward | 1800-1853 |

Sugar

The third great Southern crop – sugar – takes off in Louisiana in the 1790’s, as a replacement for lagging sales of indigo dye. Advanced know-how in raising sugar cane arrives along with immigrants from plantations in Santo Domingo. It is a form of grass that develops into bamboo like stalks which grow to 10-14 feet in height. Planting of seedling stalks occurs in the Fall, with fresh shoots appearing the following Spring, leading to summer growth and Fall harvesting.

Then begins the elaborate process by which the stalks are crushed to give up their sugar juice, which is concentrated by repeated boiling into “cane syrup” (or blackstrap molasses). Once cooled and further purified the syrup is converted into crystalized granules, first as brown sugar and, after more processing, as white sugar.

Credit goes to one Etienne de Bore (1741-1820), a Creole living on a plantation above New Orleans, and Haitian emigres, Antoine Morin and Antonio Menendez, for creating the first profitable operation to produce granulated sugar, around 1795. From there, Louisiana becomes the home of American sugar production and of some of the wealthiest planter families. The one main threat to success lies in the Louisiana weather where, unlike the Caribbean clime, a sudden frost can wipe out both a current sugar cane crop and future seedlings.

Some Of Louisiana’s Elite Sugar Families

| Names | Dates |

| Steven Minor | 1760-1815 |

| James Brown | 1766-1835 |

| Lewis Stirling | 1786-1858 |

| Michel Bringier | 1789-1847 |

| Wade Hampton II | 1791-1858 |

| John Burnside | 1810-1881 |

| Meredith Calhoun | 1805-1869 |

Cotton

Cotton of course becomes the South’s dominant agricultural crop in the 19th century. It originates along the east coast from Virginia to Florida, as “sea island cotton,” noted for its remarkably long strands of fiber. It then moves inland after Eli Whitney invents his “(en)gin” in 1794, which efficiently sorts seeds from bolls and opens the door to growing “short strand/staple cotton.” Seeds are planted in the Spring; three foot high shrubs bearing flower buds (“bolls”) appear during the summer; and the back-breaking task of harvesting occurs in the autumn.

The crop tends to be hearty as long as droughts are avoided, weeding is completed, and the two key pests (bollworms and boll weevils) are contained. Once plantations open up from Alabama to Texas, cotton becomes the dominant source of wealth across the South.

Some Of The South’s Elite Cotton Families

| Name | State | Dates |

| Dr. Stephen Duncan | Miss | 1787-1867 |

| John Manning | La | 1815-1889 |

| Joseph Acklen | La | 1816-1863 |

| John Robinson | Miss | 1811-1870? |

| Jeremiah Brown | Ala | 1800-1863 |

| Elisha Worthington | Ark | 1808-1873 |

| Dr. John C. Jenkins | Miss | 1809-1855 |

Each of these four crops requires a minimum of 600 acres (1 square mile) of land and 20+ slaves to prosper. Then come the mega-plantations with over 100 slaves, which vary widely in acreage. Jefferson’s Monticello property spans 5,000 acres or 8 square miles. Washington’s Mount Vernon is larger, at 7600 acres. One of Joshua Ward’s rice plantations, “Brookgreen,” extends over 9,000 acres, while William Aiken’s Jehossee Island is 33,000 acres, or an almost unimaginable 55 square miles.

But one thing they all have in common: success rests on owning enough slaves and then working them to near exhaustion, especially during the critical planting and harvesting seasons.