Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

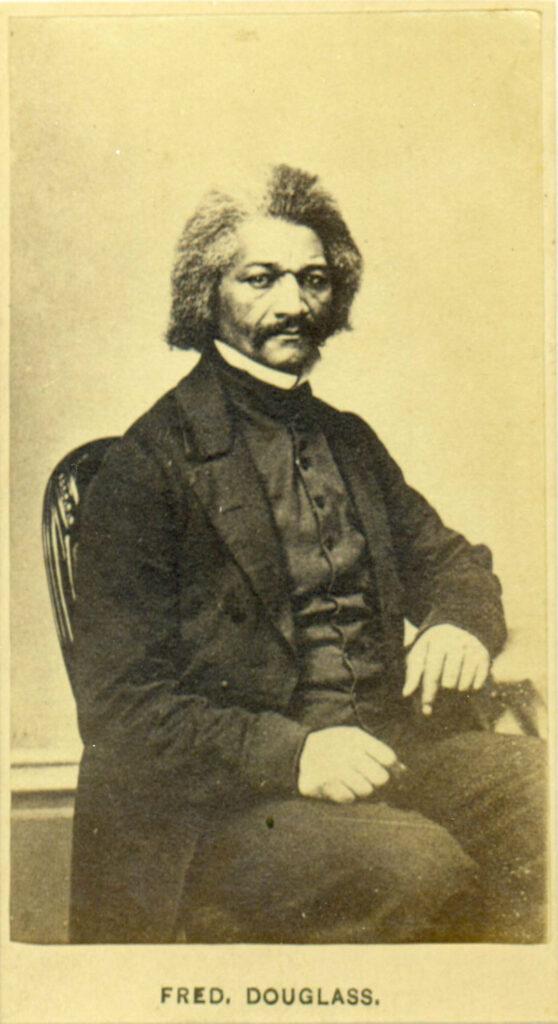

Chapter 100: Frederick Douglass Makes His First Great Speech Against Slavery

August 11, 1841

Douglass Tells His Story To The Nantucket Anti-Slavery Convention

(1818-1896)

Just as John Tyler alters the course of the Whigs first presidency, the future course of the abolition movement in America is being reshaped off the southern tip of Massachusetts.

On August 11, 1841, the Quaker abolitionist David Joy is hosting an Anti-Slavery Convention at Atheneum Hall on Nantucket Island. This is a rare mixed race event, with speakers including Lloyd Garrison and Charles Ray, the free black editor of The Coloured American newspaper.

After the formal speeches are concluded, a free black man named Frederick Douglass is invited to say a few words to the crowd about his life as a slave. As Garrison recalls in a letter written five years later, his demeanor and narration prove captivating to his audience.

A beloved friend from New Bedford prevailed on Mr. DOUGLASS to address the convention: He came forward to the platform with a hesitancy and embarrassment, necessarily the attendants of a sensitive mind in such a novel position. After apologizing for his ignorance, and reminding the audience that slavery was a poor school for the human intellect and heart, he proceeded to narrate some of the facts in his own history.

His story begins with his mixed race birth in 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland as the slave, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. He lives at The Great House Farm on a large plantation owned by a Colonel Edward Lloyd, with over 300 slaves growing tobacco, wheat and corn.

In his autobiographical Narrative, published by Garrison in 1845, Douglass recalls his first home:

There are certain secluded and out-of-the-way places, even in the state of Maryland, seldom visited by a single ray of healthy public sentiment—where slavery, wrapt in its own congenial, midnight darkness, can, and does, develop all its malign and shocking characteristics; where it can be indecent without shame, cruel without shuddering, and murderous without apprehension or fear of exposure.

His master is an overseer named Aaron Anthony, a vicious man, who terrifies the small boy by humiliating and whipping his Aunt Hester in his presence.

Anthony soon passes ownership of Douglass on to his daughter, Lucretia, who is married to Thomas Auld, also employed on Lloyd’s plantation. From there, at age seven, he is sent to Baltimore to live with Thomas Auld’s brother, Hugh, and his wife, Sophia. Douglass views this “escape” from plantation to city life as the beginning of his search for eventual freedom.

At first, Sophia Auld, who has never owned slaves, treats the boy with kindness, even agreeing to teach him the alphabet when Douglass shows curiosity about words. Her warmth, however, vanishes after Hugh warns her that educating slaves makes them rebellious and is strictly forbidden. But Sophia’s slip has opened the door to literacy for Douglass, and he is on his way to becoming a voracious, albeit clandestine, reader.

Douglass says that his time with Sophia Auld teaches him two things: the necessity of education to set blacks free; and the moral damage that institutionalized slavery can do, even to well intentioned whites like Mrs. Auld.

He remains in Baltimore for roughly seven years, working in a shipyard, and experiencing the urban world around him. The local newspapers inform him about John Quincy Adams and the early calls for abolition. He buys and devours a popular anthology called The Colombian Orator, which includes essays and speeches arguing for and against slavery. With help from dockworkers, he begins to learn how to form letters and to write words and sentences. Like Lincoln as a boy, he is educating himself.

In 1833 Hugh Auld has a falling out with his brother, Thomas, who in turn reclaims Douglass and makes him a kitchen servant in his house. When Thomas senses his independent spirit, he rents him out to a farmer named Edward Covey, known locally as a “slave breaker.” He is a thoroughly despicable man, who goes so far as to invite neighbors to sleep with his women slaves for “breeding” purposes.

Covey converts Douglass into a “field hand” for the first time, and vows to “tame” his 16 year old charge. After six months of being starved and beaten, Douglass almost gives up.

My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!

But when Covey comes again to beat him, Douglass meets violence with violence and fights him off. While he risks execution in raising a hand to his master, Covey does not want the word of this resistance to leak out, so he backs off and never tries to whip Douglass again. In his autobiography he refers to this fight as the “turning point in my life.”

You have seen how a man was made a slave; now you see how a slave was made a man.

He also comes to regard Covey and the Aulds – all ardent churchgoers – as symbols of the failure of the white Christian ministry to speak out against the evil of slavery.

In 1835, Douglass is rented out to another farmer, the more lenient William Freeland, who is rebuffed by locals for allowing him to teach slaves to read at Sunday school services. At this point, Douglass ponders an escape, but his plans are foiled. He returns to Baltimore where Hugh Auld puts him to work as a caulker in a shipyard.

Again, Douglass makes the most of his chances here in a broader external world. He joins the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society, where free blacks hold debates. Through Society he meets and falls in love with Anna Murray, a housekeeper. He is now 19 years old and on the brink of his escape to freedom.

His break occurs on September 3, 1838. With help from Anna, Douglass dons a red shirt, tarpaulin hat and black scarf posing as a free black sailor and moves by boat and train from Maryland to Delaware to Philadelphia and finally New York City, where he is housed by the African abolitionist, David Ruggles. Anna Murray follows him there and they are married two weeks later. He is given a new last name by a friend, Nathan Johnson, to help conceal his run away status. The name is Douglass, after a hero in Sir Walter Scott’s epic poem, Lady of the Lake.

Douglass and Anna settle down in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he takes on a series of menial jobs while searching for his new identity in free society. He joins the local African Methodist Episcopalian Zion Church. He subscribes to Garrison’s paper, The Liberator, and begins to sense his calling. In April 1839 he hears Garrison lecture in New Bedford, and decides to attend a convention of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, held on Nantucket Island.

This event will change the arc of his future life.

August 1841

Garrison Reacts To Douglass’s Talk

Those listening to Douglass on Nantucket are both moved by his narrative and surprised by the eloquence of his delivery. Garrison writes:

I shall never forget his first speech at the convention-the extraordinary emotion it excited in my own mind -the powerful impression it created upon a crowded auditory, completely taken by surprise- the applause which followed from the beginning to the end of his felicitous remarks.

Garrison sees in Douglass a confirmation of his belief that Africans possess all the natural capacities of whites, if only given support and a small amount of cultivation.

I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment; certainly, my perception of the enormous outrage which is inflicted by it, on the godlike nature of its victims, was rendered far more clear than ever. There stood one, in physical proportion and stature commanding and exact-in intellect richly endowed-in natural eloquence a prodigy-in soul manifestly “created but a little lower than the angels”-yet a slave, ay, a fugitive slave,- trembling for his safety, hardly daring to believe that on the American soil, a single white person could be found who would befriend him at all hazards, for the love of God and humanity! Capable of high attainments as an intellectual and moral being-needing nothing but a comparatively small amount of cultivation to make him an ornament to society and a blessing to his race-by the law of the land, by the voice of the people, by the terms of the slave code, he was only a piece of property, a beast of burden, a chattel personal, nevertheless!

Garrison compares Douglass’ pleas for liberty and justice to those announced by Patrick Henry.

As soon as he had taken his seat, filled with hope and admiration, I rose, and declared that PATRICK HENRY, of revolutionary fame, never made a speech more eloquent in the cause of liberty, than the one we had just listened to from the lips of that hunted fugitive. So I believed at that time–such is my belief now.

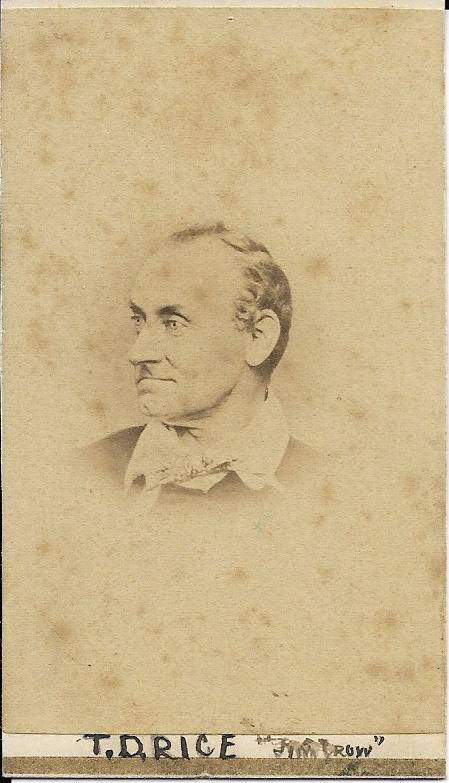

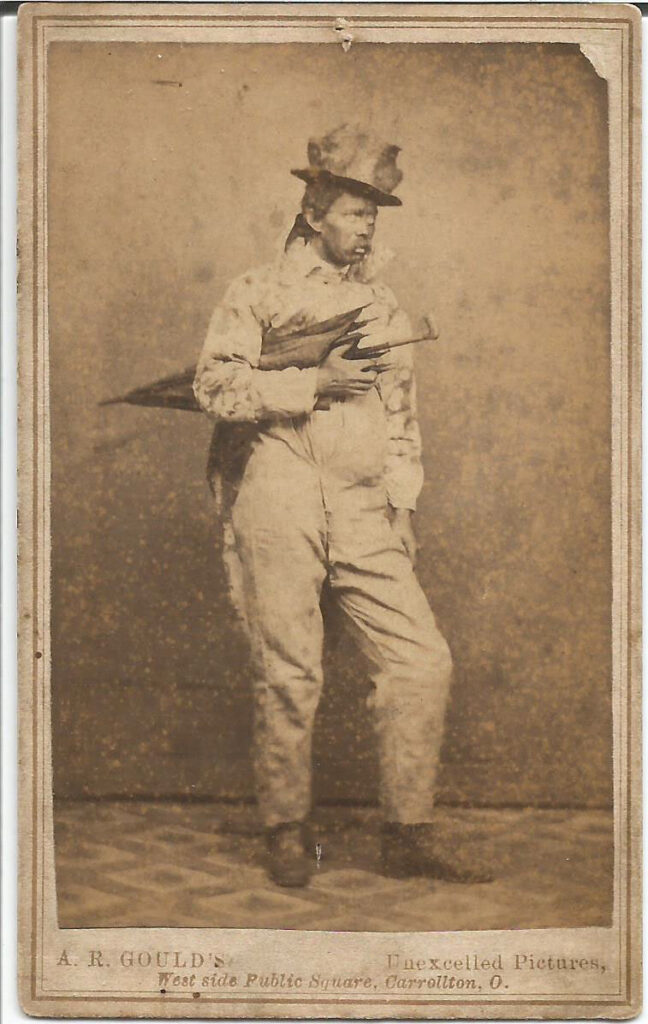

Sidebar: Thomas Rice and the Legacy of “Jim Crow”

While the abolitionist attendees at Nantucket are hearing the articulate Fred Douglass recount his history as a slave, other white audiences are watching the actor Thomas Rice reinforce their anti black racial prejudices in America’s theaters Rice’s fame rests on a single blackface routine featuring his character, “Jim Crow,” whose stereotypical behaviors are intended to draw mocking derision and laughter. The highlight of Rice’s performance is a soft shoe dance titled “Jump Jim Crow,” accompanied by nonsense lyrics delivered in a broken drawl. Throughout the 1840’s Rice plays before packed houses in both the U.S. and in London.

(1808-1860)