Section #7 - A populist western president stands against Nullification and for tribal relocation

Chapter 62: The French Visitor Alexis de Tocqueville Analyzes The American Spirit And The Regional Tensions Around Slavery

1831-1832

de Tocqueville Completes A Tour Of America

On May 9, 1831, two young men involved with the French judicial system arrive in Newport, Rhode Island, after a 37 day long Atlantic crossing. One is Gustave de Beaumont, a 29 year old “King’s Prosecutor” in Paris. The other is his 25 year old friend, Alexis de Tocqueville, currently serving as a court appointed judge.

Their intent is to study North America’s prison system in hopes of finding reform ideas they can apply in France.

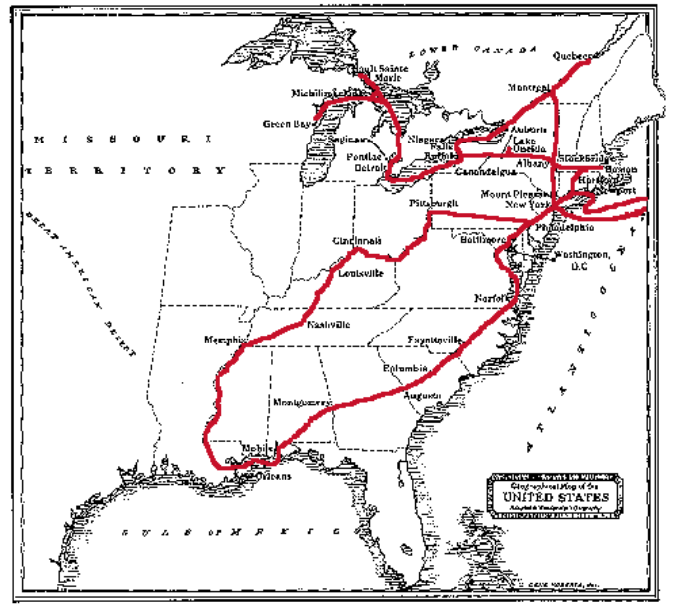

To do so, they set off on a nine-month journey, utilizing ships and steamboats, stagecoaches and footpaths, to cut a wide swath across the eastern half of the continent.

de Tocqueville’s Itinerary in North America

| Dates | Location |

| May 9, 1831 | Arrive in Newport, Rhode Island |

| May 29 | Visit Ossining (Sing Sing) Prison |

| June 7 | New York City |

| July 9 | Visit Auburn Prison in New York |

| July 1 | Arrive in Detroit |

| August 9 | At Green Bay (Michigan Territory) |

| August 19 | Back toward east, at Niagara Falls |

| August 23 | Montreal |

| September 9 | Boston |

| October 12 | Interviewing prisoners at Cherry Hill |

| November 22 | Pittsburg |

| December 1 | Cincinnati |

| December 17 | Memphis |

| January 1 | New Orleans |

| January 3 | Mobile |

| January 15 | Norfolk, Virginia |

| January 17 | Washington, DC |

| February 3 | Philadelphia |

| February 20 | Depart from New York to France |

Along the way, de Tocqueville records his detailed observations about America in a diary, which he analyzes upon his return home. Together with de Beaumont he publishes Du systeme penitentiaire aux Etats-Unis et de son application en France, to fulfill the purpose of the trip.

But de Tocqueville remains fascinated with what he has seen and learned on his whirlwind tour, and decides to publish a second book. He titles it Democracy In America, with the first volume published in August 1834, and the second in 1840. The book captures de Tocqueville’s experiences and conclusions about a broad range of topics.

Table of Contents: Democracy in America- Part 1

| Volume 1 (1834) |

| The Author’s Preface |

| The Exterior Form of North America |

| Origins of the Anglo-Americans |

| Social Conditions of the Anglo-Americans |

| The Principle of the Sovereignty of the People |

| The Necessity of Examining the States Before The Union At Large |

| Judicial Power In the U.S. and its Influence on Political Society |

| The Federal Constitution |

| How it can be Strictly Said That the People Govern in the US |

| Liberty of the Press in the US |

| Political Associations in the US |

| Government of the Democracy in the US |

| What Advantages American Society Derives from Democracy |

| Unlimited Power of the Majority and Its Consequences |

| Causes Which Mitigate the Tyranny of the Majority |

| Principle Causes Which Serve To Maintain a Democratic Republic |

| The Present and Probably Future Condition of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States |

Overall what de Tocqueville seems to find most profoundly intriguing about America is the “philosophical approach” adopted by its citizens in relation to whatever topics or issues they encounter.

Gone are the old answers to all things, imposed from above by kings or clergymen – replaced by every man using his own common sense and experience to arrive at his own beliefs.

de Tocqueville describes this as follows:

I THINK that in no country in the civilized world is less attention paid to philosophy than in the United States. The Americans have no philosophical school of their own, and they care but little for all the schools into which Europe is divided, the very names of which are scarcely known to them.

Yet it is easy to perceive that almost all the inhabitants of the United States use their minds in the same manner, and direct them according to the same rules; that is to say, without ever having taken the trouble to define the rules, they have a philosophical method common to the whole people.

I discover that in most of the operations of the mind each American appeals only to the individual effort of his own understanding.

To evade the bondage of system and habit…class opinions…of national prejudices; to accept tradition only as a means of information, and existing facts only as a lesson to be used in doing otherwise and doing better; to seek the reason of things for oneself, and in oneself alone; to tend to results without being bound to means, and to strike through the form to the substance–such are the principal characteristics of what I shall call the philosophical method of the Americans

From this uniquely American way of thinking comes a genuine experiment in democracy, which, for the Frenchman, explains the “social conditions” of the new nation. He summarizes this in bold type as follows:

THE STRIKING CHARACTERISTIC OF THE SOCIAL CONDITION OF THE ANGLO AMERICANS IS ITS ESSENTIAL DEMOCRACY.

In turn, he pens the line for which he will be most memorialized in the United States:

America is great because she is good, and if America ever ceases to be good, she will cease to be great.

1831-1832

The Frenchman Comments On Regional Differences In America

While de Tocqueville sees philosophical similarities across all Anglo-Americans, he distinguishes between the societal milieus he finds in the North vs. the South.

His view is that the South has been shaped by the dominance of slavery which has “benumbed” the entire region and left it diminished by “ignorance and pride.”

Virginia received the first English colony…in 1607…. The colony was scarcely established when slavery was introduced; this was the capital fact which was to exercise an immense influence on the character, the laws, and the whole future of the South.

Slavery, as I shall afterwards show, dishonors labor; it introduces idleness into society, and with idleness, ignorance and pride, luxury and distress. It enervates the powers of the mind and benumbs the activity of man. The influence of slavery…explains the manners and the social condition of the Southern states.

By contrast, de Tocqueville sees the North rooted in the Puritanism of the New England states, with values shining “like a beacon lit upon a hill.” Theirs was never a mad search for wealth and title, but rather the “triumph of an idea” – to create a society where they could “worship God in freedom” and translate religious principles into a political reality for the common good.

In the English colonies of the North…the two or three main ideas that now constitute the basis of the social theory of the United States were first combined… The civilization of New England has been like a beacon lit upon a hill, which, after it has diffused its warmth immediately around it, also tinges the distant horizon with its glow….

The settlers who established themselves on the shores of New England all belonged to the more independent classes of their native country… a society containing neither lords nor common people, and we may almost say neither rich nor poor. These men possessed, in proportion to their number, a greater mass of intelligence than is to be found in any European nation of our own time.

Nor did they cross the Atlantic to improve their situation or to increase their wealth; it was a purely intellectual craving that called them from the comforts of their former homes; and in facing the inevitable sufferings of exile their object was the triumph of an idea…. the Puritans went forth to seek some rude and unfrequented part of the world where they could live according to their own opinions and worship God in freedom…. Puritanism …was almost as much a political theory as a religious doctrine.

1831-1832

Views On The Plight Of The Africans Living In America

The scope of de Tocqueville’s travels sensitizes him to the fact that three distinct races are attempting to live in proximity to each other on the continent.

Three races are discoverable among them at the first glance although they are mixed, they do not amalgamate, and each race fulfills its destiny apart.

As a white man himself, he identifies the Anglo-Americans as superior in intelligence, and using this capacity to subjugate both the Africans and the Native Tribes.

Among these widely differing families of men, the first that attracts attention, the superio in intelligence, in power, and in enjoyment, is the white …below him appear the Negro and the Indian…Both of them occupy an equally inferior position in the country they inhabit; both suffer from tyranny; and if their wrongs are not the same, they originate from the same authors.

If we reason from what passes in the world, we should almost say that the European is to the other races of mankind what man himself is to the lower animals: he makes them subservient to his use, and when he cannot subdue he destroys them.

While both minorities suffer in the relationship, it is the enslaved Africans who are “deprived of almost all the privileges of humanity.”

Oppression has, at one stroke, deprived the descendants of the Africans of almost all the privileges of humanity.

The Negro of the United States has lost even the remembrance of his country; the language which his forefathers spoke is never heard around him; he abjured their religion and forgot their customs when he ceased to belong to Africa, without acquiring any claim to European privileges. But he remains half-way between the two communities, isolated between two races; sold by the one, repulsed by the other; finding not a spot in the universe to call by the name of country, except the faint image of a home which the shelter of his master’s roof affords. The Negro has no family…The Negro enters upon slavery as soon as he is born…Equally devoid of wants and of enjoyment, and useless to himself, he learns, with his first notions of existence, that he is the property of another.

As de Tocqueville sees it, the response to slavery among the African-Americans is every bit as devastating as the condition itself – for intimidation destroys the innate sense of self-worth and identity and replaces it with an instinct to imitate the traits of white masters for the sake of survival.

Once one is officially declared to be 3/5th of a full person, the road back to full equality becomes steep. And it explains why, when the time comes, the roll call of black abolitionists will all rally around a common battle cry – “I am a man” or “I am a woman.”

The Negro makes a thousand fruitless efforts to insinuate himself among men who repulse him; he conforms to the tastes of his oppressors, adopts their opinions, and hopes by imitating them to form a part of their community. Having been told from infancy that his race is naturally inferior to that of the whites, he assents to the proposition and is ashamed of his own nature. In each of his features he discovers a trace of slavery, and if it were in his power, he would willingly rid himself of everything that makes him what he is.

Like the Anglo-Americans of his time, de Tocqueville is not sanguine about emancipation as the path to reversing the damage done by slavery.

If he becomes free, independence is often felt by him to be a heavier burden than slavery…In short, he is sunk to such a depth of wretchedness that while servitude brutalizes, liberty destroys him.

1831-1832

Views On The Native American Tribes

de Tocqueville’s belief about the Indians he encounters is somewhat more nuanced than his views on the Africans.

Again, as a white man, he regards them as intellectually inferior, and even “savage” in terms of their natural inclinations. At the same time, he clearly senses something noble in their presence, and, citing the Cherokees, concludes that they “are capable of civilization.”

Prior to the European invasion, the Native American existed in a pure state of nature and liberty.

Before the arrival of white men in the New World, the inhabitants of North America lived quietly in their woods, enduring the vicissitudes and practicing the virtues and vices common to savage nations.

The Indian lies on the uttermost verge of liberty; To be free, with him, signifies to escape from all the shackles of society. As he delights in this barbarous independence and would rather perish than sacrifice the least part of it, civilization has little hold over him.

That freedom is disappearing as the eastern tribes are being driven out of their homelands to suit the wishes of white settlers. The result is “inexpressible sufferings.”

The Europeans having dispersed the Indian tribes and driven them into the deserts, condemned them to a wandering life, full of inexpressible sufferings.

The Frenchman also argues that displacement has only served to make the tribes more “disorderly and barbarous” than they once were.

Oppression has been no less fatal to the Indian than to the Negro race, but its effects are different. Savage nations are only controlled by opinion and custom. When the North American Indians had lost the sentiment of attachment to their country; when their families were dispersed, their traditions obscured, and the chain of their recollections broken; when all their habits were changed, and their wants increased beyond measure, European tyranny rendered them more disorderly and less civilized than they were before. The moral and physical condition of these tribes continually grew worse, and they became more barbarous as they became more wretched.

Still, de Tocqueville seems to hold out some hope of ultimate civilization for the tribes – achieved “by degrees and by their own efforts.”

Nevertheless, the Europeans have not been able to change the character of the Indians; and though they have had power to destroy, they have never been able to subdue and civilize them.

The success of the Cherokees proves that the Indians are capable of civilization, but it does not prove that they will succeed in it. This difficulty that the Indians find in submitting to civilization proceeds from a general cause, the influence of which it is almost impossible for them to escape. An attentive survey of history demonstrates that, in general, barbarous nations have raised themselves to civilization by degrees and by their own efforts.

1831-1832

His Prescient Observations About Future Regional Conflict

While amazed by the American experiment in democracy, de Tocqueville is not oblivious to underlying conflicts that could bring the nation down.

He picks this up particularly around the “Nullification Crisis” that is swirling around during his visit – something he attributes in part to the envy of declining Southern states versus those on the rise in the North.

The states that increase less rapidly than the others look upon those that are more favored by fortune with envy and suspicion. Hence, arise the deep-seated uneasiness and ill-defined agitation which are observable in the South and which form so striking a contrast to the confidence and prosperity which are common to other parts of the Union.

I am inclined to think that the hostile attitude taken by the South recently [in the Nullification Crisis] is attributable to no other cause. The inhabitants of the Southern states are, of all the Americans, those who are most interested in the maintenance of the Union; they would assuredly suffer most from being left to themselves; and yet they are the only ones who threaten to break the tie of confederation.

In addition, the South is also losing its control over government decision at the federal level.

It is easy to perceive that the South, which has given four Presidents to the Union, which perceives that it is losing its federal influence and that the number of its representatives in Congress is diminishing from year to year, while those of the Northern and Western states are increasing, the South, which is peopled with ardent and irascible men, is becoming more and more irritated and alarmed. Its inhabitants reflect upon their present position and remember their past influence, with the melancholy uneasiness of men who suspect oppression.

Thus, it tries to fight back by arguing that laws like The Tariff are biased against them, and, unless reversed, their only recourse will be to “quit the association.”

If they discover a law of the Union that is not unequivocally favorable to their interests, they protest against it as an abuse of force; and if their ardent remonstrances are not listened to, they threaten to quit an association hat loads them with burdens while it deprives them of the profits. “The Tariff,” said the inhabitants of Carolina in 1832, “enriches the North and ruins the South; for, if this were not the case, to what can we attribute the continually increasing power and wealth of the North, with its inclement skies and arid soil; while the South, which may be styled the garden of America, is rapidly declining.”

de Tocqueville concludes by arguing that what he sees as Southern envy of the North does the region no good. Its potential to “increase more rapidly than any kingdom in Europe” remains. In applying itself against its “true interests” rather than placing blame on the North, the prospect of future war can be averted.

…It must not be imagined, however, that the states that lose their preponderance also lose their population or their riches; no stop is put to their prosperity, and they even go on to increase more rapidly than any kingdom in Europe. But they believe themselves to be impoverished because their wealth does not augment as rapidly as that of their neighbors; and they think that their power is lost because they suddenly come in contact with a power greater than their own. Thus they are more hurt in their feelings and their passions than in their interests.

But this is amply sufficient to endanger the maintenance of the Union. If kings and peoples had only had their true interests in view ever since the beginning of the world, war would scarcely be known among mankind.