Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 39: America’s First Economic Depression

1812-1814

The War Of 1812 Prompts A “Boom Cycle” In America’s Economy

From his first day in office, James Monroe is plagued by the economic troubles he inherits from his predecessor.

These materialize out of the “boom-bust cycle” that begins in 1812 as America gears up to fight the war with Britain.

A continental army needs to be formed and equipped, housed and fed, transported and re supplied, all in a short time frame and with no clear-cut end in sight. Additionally, the British blockade of American ports greatly increased the need for domestically produced goods.

“Boom Cycle” During War Of 1812

| GDP | 1812 | 1813 | 1814 |

| $ 000 | 786 | 969 | 1,078 |

| % Ch | 2% | 23% | 11% |

| Per Cap | 103 | 123 | 133 |

Taken together, this increased “demand” represented a windfall opportunity for a host of suppliers – who turn to local bankers to borrow the money needed to invest in added capacity.

The banks are only too happy to comply with this increased demand for more loans, often at higher than usual rates of interest.

But many face a problem: a lack of sufficient cash on hand to complete the loans.

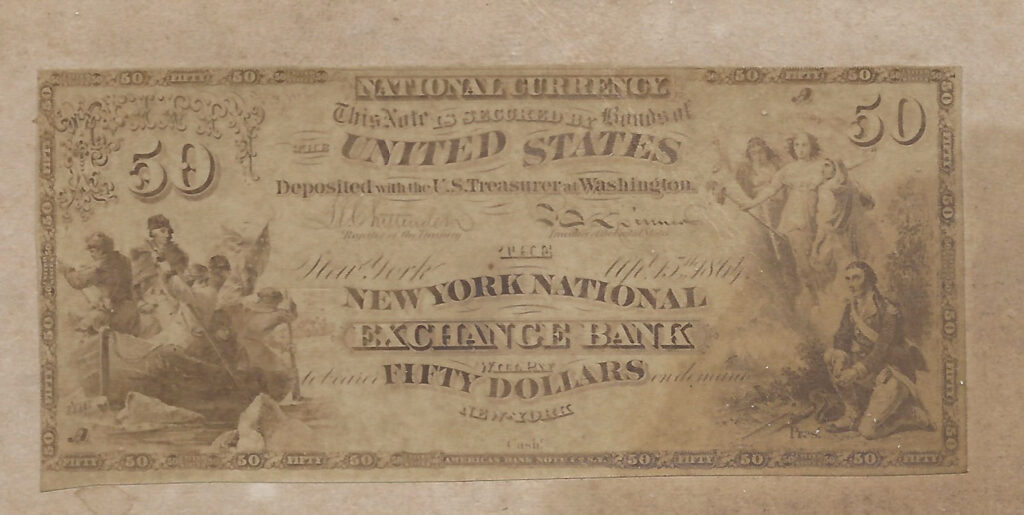

They solve this problem by resorting to a time-honored tactic – simply printing and issuing more soft money banknotes, while ignoring the rules about properly “backing them” with reserves of gold or silver.

The result is a sharp increase in the money supply in circulation, followed by inflation.

The price of goods across the economy goes up in response to a decline in the “true value/buying power” of each dollar in the system.

And, in 1812, there is no longer a federal Bank of the United States in place to curtail the runaway printing of soft money unrelated to specie on hand. That’s because Jefferson views the BUS as another of Hamilton’s monarchistic devices to centralize governmental power – and he allows its charter to expire in 1811.

By 1813 then the American economy is enjoying a flat-out “boom cycle.”

Those who have taken out loans for investment are reaping large gains in profit, and are able to pay off their debts to the banks in full and on time. In turn, bankers are able to meet their payments to depositors, while also increasing their own private profits.

1815-1816

A “Bust Cycle” Follows When The War Ends

The increased prosperity continues until the war with Britain comes to a close in 1815.

At which time, the ramped-up “demand” for goods suddenly drops, and suppliers find themselves with excess inventory they can’t sell, along with excess operating costs they need to shed.

The more conservative investors are able to work their way back to a sustainable equilibrium, but others are left with crippling financial losses.

When their banks demand pay back on their loans taken, they are left in default. This signals the shift from “boom cycle to bust cycle.”

The rapid economic growth evident in 1813 and 1814 disappears, and down years take over.

“Bust Cycle” Begins At End Of War

| 1814 | 1815 | 1816 | |

| $ 000 | 1,078 | 925 | 819 |

| % Ch | 11% | (14%) | (11%) |

| Per Cap | $133 | 111 | 96 |

The early losses materialize in 1815 and 1816, while Madison is still in office. Aggregate demand for goods drops, along with production. Prices increase as the excess money supply leads on to inflation.

As alarm sets in, Treasury Secretary Gallatin finally persuades Madison to reverse his opposition to Hamilton’s financial model, and the Second Bank of the United States is approved in 1816.

Its role is twofold:

- To restore credibility to the nation’s supply of soft money and thereby tamp down inflation; and

- To expand the revenue available to the federal government through the issuance of treasury bonds.

In 1817 the burden falls on Monroe and Crawford to successfully execute this strategy.

1817-1818

America’s First Prolonged Depression Sets In

Nothing they do, however, can unwind the problems facing the banking system – in what will go down as the “Financial Panic of 1819.”

Because once the bankers are out on a limb, wantonly printing money to chase windfall profits, there are no easy fixes if the loans they’ve made cannot be paid back.

By 1818 that outcome is all too often the norm.

Widespread defaults on loans rapidly upsets the delicate cash flow balance that keeps banks viable.

Incoming cash from interest on their loans falls short of outgoing cash needed to pay interest to depositors.

The banks are now in a spiraling “money squeeze” of their own.

In an often desperate search for more incoming cash, the banks “foreclose” on customers whose loans are in default. But these foreclosures often leave them with assets (e.g. homes, farms, goods) they don’t want to hold and can only sell at rock bottom prices.

Public protests call for “stay laws” to delay loan repayments and foreclosures, as general hostility toward banks spreads. Ohio congressman William Henry Harrison captures this anger, when he says:

I hate all banks!

As the “squeeze” on local banks continues, the Second Bank of the United States launches a new policy that will make things even more difficult in the short-run.

It requires that state banks complete future transactions with the BUS using gold or silver specie rather than paper currency. (Andrew Jackson will repeat this same tactic some seventeen years hence.)

On the surface, the rationale for this move is sound. The federal government itself still needs to pay off sizable loans made by foreign investors during the 1812 War – and the demand here is for gold or silver coins rather than soft money. In addition, transactions in specie are also intended to reassert the need for adequate bank reserves, reduce over-printing of soft currency and reduce inflation. All worthy goals.

But many local banks who wish to borrow money from the BUS to offset their cash flow problems now find that “window” closed to them because their inventory of specie is too limited.

All that’s left for them at this point is to refuse payments of interest to their depositors – and when this happens, panic sets in among their customers. “Runs on banks” pop up around the country, as depositors line up to withdraw their life’s savings before whatever cash left on hand runs out.

This simply accelerates the downward cycle until the target banks are forced to close their doors.

In 1818 the Bank of Kentucky suspends all operations – a fate shared by roughly 30% of the nation’s 420 state banks over the course of the panic.

1819-1820

Time Alone Ends The Downturn

As 1819 plays out, all that can go wrong with America’s capitalistic system has gone wrong.

The allure of windfall profits has upped the demand for speculative loans. Banks respond by wantonly printing paper money not backed by gold or silver reserves. Uncontrolled expansion of the money supply erodes the true value of cash and leads to damaging price inflation. The anticipated windfall profits dry up due to a sudden change in external conditions (in this case, the end of the war). When loans come due, borrowers are unable to pay them off. Defaults upset the bank’s cash flow balance and they lack the money needed to pay interest due on deposits. Panic sets in among all depositors leading to “runs” on banks who are then forced to shut down.

Unfortunately, history will show this pattern of economic boom and bust repeating itself in America every two decades or so – thus the panics of 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, 1907, 1929, and so forth.

Many lives are damaged by its effects.

In Pennsylvania, land values plummet from $150 per acre in 1815 to $35 in 1819. Over 50,000 men are unemployed in Philadelphia, and some 1800 are sent to debtor’s prison. Beggars appear on city streets, along with soup kitchens and homeless shelters.

Senator John Calhoun sums up conditions in 1820:

There has been within these two years an immense revolution of fortunes in every part of the Union; enormous numbers of persons utterly ruined; multitudes in deep distress.

In the end, the depression extends over six years, roughly from 1815 to 1820 – although GDP per capita remains depressed until many years later.

GDP Trends During The Depression Following The War Of 1812

| 1814 | 1815 | 1816 | 1817 | 1818 | 1819 | 1820 | 1821 | 1822 | 1823 | 1824 | 1825 | |

| $ 000 | 1,078 | 925 | 819 | 769 | 737 | 726 | 710 | 735 | 805 | 759 | 754 | 822 |

| % Ch | 11% | (14%) | (11%) | (6%) | (4%) | (2%) | (2%) | 3% | 9% | (6%) | (1%) | 9% |

| Per Cap | $133 | 111 | 96 | 87 | 81 | 78 | 74 | 74 | 79 | 72 | 70 | 74 |

Government policies do not escape criticism during the downturn – and ominously some of the anger takes on a sectional tone.

When first passed in April 1816, the “Dallas Tariff” on imported goods is almost universally approved.

But three years later, as the depression drags on with Monroe in office, it begins to come under attack.

The South wants the tariff lowered — so that prices on finished goods (e.g. clothing) from Europe will fall, domestic sales will grow, and the export market for raw cotton will spike up, along with planter’s profits.

New Englanders want exactly the opposite. Aside from raising federal revenue, the tariff was adopted to “protect” American manufacturing of finished goods – by keeping the prices of domestically produced goods below their European competition.

This North-South tension over the tariff is soon to be further fueled in 1820 by controversies surrounding admission of Missouri as the 23rd state in the Union.