Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 99: Tyler Turns Against The Whigs And They Turn Against Him

August 6, 1841

The Whigs Pass A Fiscal Bank Bill

The Whigs victory in 1841 is driven in large part by public anger over the uncertain currency and sluggish economy that has plagued the country since Jackson’s “Specie Circular” order and the subsequent Panic of 1837.

A year earlier, on July 4, 1840, Van Buren finally gets congressional support to create his Independent U.S. Treasury, where all federal revenues received are held in a “public entity” (the Treasury Department) rather than being distributed to “private state banking corporations,” whose motives are forever distrusted by the Democrats.

While this approach does help stabilize the currency, it also bureaucratic in nature — slowing down the circulation of capital to private entrepreneurs willing to take the risks to grow their own wealth and that of the total economy.

Men like Henry Clay, who are intent on aggressively boosting investment in roads, bridges, canals, trains and other “infrastructure enablers,” argue that the U.S. will lag behind as long as risk-averse Government investors in charge of the capital.

Their solution lies in chartering the Third Bank of the United States, after the shut down of the first in 1811 by Jefferson, and the second by Jackson in 1833.

Starting in May 1841 Clay pleads with Tyler to support this bank. When Tyler says he needs more time to consider the matter, Clay says that his answer is unacceptable. Tyler’s comeback signals the end of all hope for comity between the two:

Then, sir, I wish you to understand this — that you and I were born in the same district; that we have fed upon the same food, and have breathed the same natal air. Go you now then, Mr. Clay, to your end of the avenue, where stands the Capitol, and there perform your duty to the country as you shall think proper. So help me God, I shall do mine at this end of it as I shall think proper

Clay proceeds to repeal Van Buren’s Independent Treasury Act and then come forward with his replacement, camouflaged as the “Fiscal Bank,” which Congress approves on August 6, 1841.

The language in the Act is intended to force Tyler’s hand, since it “mandates” that each state create a branch, whether or not their legislature supports it. Were the President to approve this wording, it would alienate the state’s rights Democrats and bring Tyler to heel as a Whig; on the other hand, a veto would reveal his true colors as a Jeffersonian.

Tyler recognizes the trap, saying to friends:

My back is to the wall, and while I deplore the assaults, I shall…beat back the assailants…Those who all along have opposed me will still call out for further trials, and thus leave me impotent and powerless.

August 15 – September 9, 1841

Tyler Issues Two Vetoes

On August 15 Tyler vetoes the “Fiscal Bank” bill, as unconstitutional,

Democrats salute the veto, while Whigs are appalled:

Poor Tippecanoe! It was an evil hour that “Tyler too” was added to make out the line. There was rhyme, but no reason to it.

Clay launches into a ninety-minute diatribe in the Senate against Tyler on August 18, suggesting that he resign. He is joined in the House by John Minor Botts, a Virginian previously friendly with Tyler, who now accuses the President of lying to him all along about his support for the new bank.

In the early morning of August 19, a drunken mob pelts the White House with rocks and fires off guns, frightening Tyler’s frail and reclusive wife, Leticia, and further upsetting the President. He asks that a police force be approved to guard the mansion.

Clay is anything but the Great Compromiser at this moment, and returns to Congress with a slightly revised bill featuring a name change. What was the “Fiscal Bank” is now cast as the “Fiscal Corporation.”

This passes Congress on September 3.

Tyler picks up the gauntlet and vetoes it on September 9, accompanied by another message to the people:

I distinctly declared that my own opinion had been uniformly proclaimed to be against the exercise “of the power of Congress to create a national bank to operate per se over the Union,”

…It is with great pain that I now feel compelled to differ from Congress a second time in the same session…It has been my good fortune and pleasure to concur with them in all measures except this. And why should our difference on this alone be pushed to extremes? It is my anxious desire that it should not be. I too have been burdened with extraordinary labors of late, and I sincerely desire time for deep and deliberate reflection on this the greatest difficulty of my Administration. May we not now pause until a more favorable time, when, with the most anxious hope that the Executive and Congress may cordially unite, some measure of finance may be deliberately adopted promotive of the good of our common country?

September 11-13, 1841

Tyler’s Cabinet Resigns And He Is Drummed Out Of The Party

Events now move quickly and dramatically.

Tyler has sensed all along that his cabinet is against him.

(I am) surrounded by Clay men, Webster men, Anti-Masons, original Harrisons, old Whigs and new Whigs. (and) not a single sincere friend…

He is proven right just two days after his second veto, on September 11, when every member, except for Secretary of State Daniel Webster, turns in his resignation.

Clay believes, or at least hopes, that Tyler will also resign, and that, as Senate President pro tempore, he will be elevated to the office he deserves.

Tyler is bolstered, however, by Webster’s decision to stay on, and, in so doing, to oppose Clay. He is also ready to name a replacement cabinet, and does so promptly. They are regionally balanced and all are professed Whigs, except for Hugh Legare, a “Unionist Democrat” who opposed John Calhoun’s call for nullification.

John Tyler’s “Replacement” Cabinet

| Position | Name | Home State |

| Secretary of State | Daniel Webster | Massachusetts |

| Secretary of Treasury | Walter Forward | Pennsylvania |

| Secretary of War | John C. Spencer | New York |

| Attorney General | Hugh Legare | South Carolina |

| Secretary of Navy | Abel Upshaw | Virginia |

| Postmaster General | Charles Wickliffe | Kentucky |

The fact that Tyler is able to recruit these Whigs gives him hope and confirms the presence of an anti-Clay wing of the party that helped Harrison win the 1840 nomination in the first place.

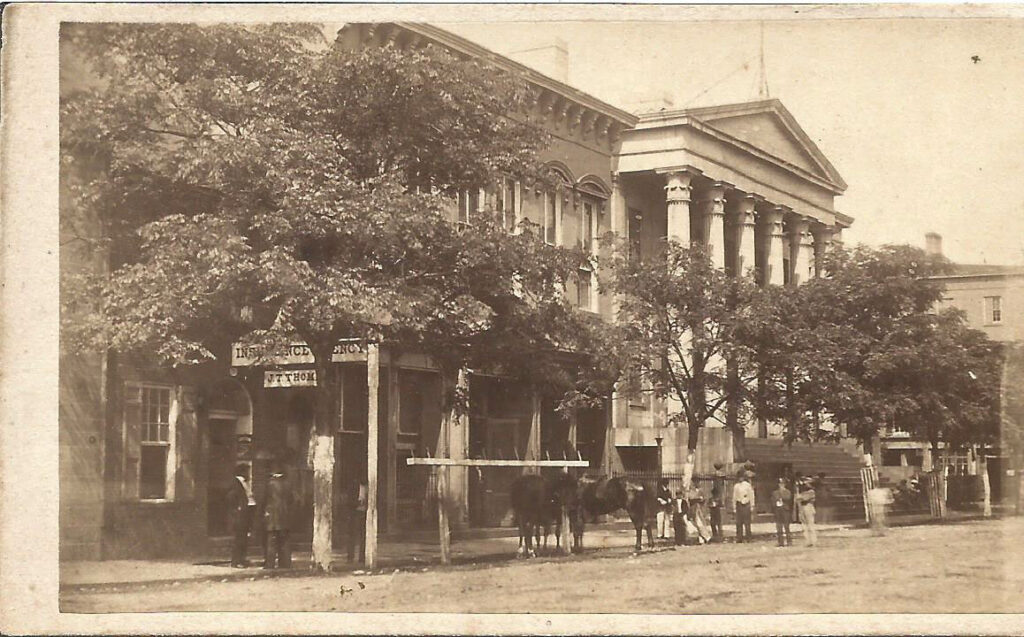

On September 13 some 50-80 “Clay men” in Congress gather at Capitol Square and formally expel Tyler from the Whig Party. The President records his own thoughts on this and on his plan for the future, which will have a distinctly Democratic cast to it.

I shall act upon the principles which I have all along espoused…derived from the teachings of Jefferson and Madison.

Meanwhile, in sticking with Tyler, Webster dooms his chances of becoming President. He will try twice for the Whig nomination, losing both in 1848 and 1852.