Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 107: John Fremont’s First Expedition Reaches The “South Pass”

May 22, 1842

The 1842 Fremont Expedition To The “South Pass” Is Organized

Between 1842 and 1854, frontiersman, topographical engineer and future presidential candidate, John C. Fremont will complete five separate expeditions to the west.

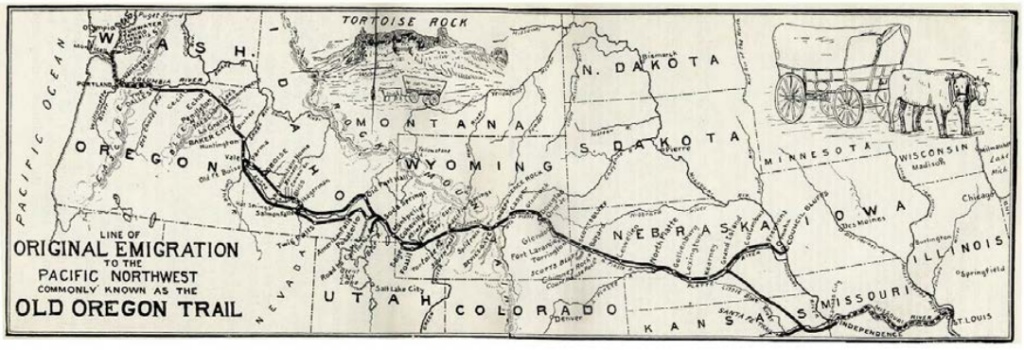

By the time Congress sets aside $30,000 to fund his first trip west, the main routes he will follow – along the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails – have been thoroughly “blazed” by a host of prior tribesmen and trappers alike.

However, as of 1842, none of them have produced reliable maps or detailed descriptions of the trails. Fremont lays out the scientific process required.

There was a mass of astronomical and other observations to be calculated and discussed before a beginning on [a map] could be made. Indeed, the making of such a map is an interesting process. It must be exact. First, the foundations must be laid in observations made in the field; then the [mathematical] reductions of these observations to latitude and longitude; afterward the projection of the map, and the laying down of positions fixed by the observation; then the tracings from the sketch-books of the lines of the rivers, the forms of the lakes, the contours of the hills. Specially, it is interesting to those who have laid in the field these foundations, to see them all brought into final shape–fixing on a small sheet the results of laborious travel over waste regions, and giving to them an enduring place on the world’s surface.

The tasks will fall to Freeman and his various companions.

The initial 1842 expedition is led by three men, each uniquely qualified for the journey.

In overall command is 2nd Lt. John Fremont, who joins the U.S. Army Topographical Engineers Corp in 1838. His background is anything but conventional.

His mother, Anne, is the daughter of a wealthy Virginia planter whose estate is dissipated, leaving her to fend for herself. She marries an elderly Richmond man, then carries on an affair with a French ex-patriot, Charles Fremon, who had fought for the monarchy. Together they have an out-of-wedlock son, John Fremon, in 1813. After two years at The College of Charleston, Fremon embarks on a military career, teaching mathematics aboard a naval sloop. His interests shift to topographical engineering and, in 1838, he begins to survey land west of St. Louis, where the Missouri River, flowing eastward from the Rockies, empties into the Mississippi River.

In 1840, Fremont (who has added a “t” to his name) is in Washington, D.C. to report on his survey, where he meets Jessie Benton, the 15 year old daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton. Jesse has been reared like a son by her powerful father, Missouri’s first senator since 1821, a fierce Jackson man, and a leading advocate of U.S. territorial expansion. Much to his chagrin, the ever willful Jessie elopes with Fremont in 1841.

Reconciliation follows banishment, and in 1842 Benton secures a commission for Fremont to begin “mapping the west,” a journey that will eventually lead on to his sobriquet as “The Pathfinder” and to future fame.

As his designated expedition “guide,” Fremont selects Christopher “Kit” Carson, who grows up in Franklin, Missouri, along the Santa Fe Trail, on land his father purchases from Daniel Boone. He is a restless youth, and in 1826, at age 17, sets out West with a band of trappers. Over the next 15 years, he becomes a well-known “mountain man,” hunting and trading up and down the Rocky Mountains, while often living among the various Indian tribes. Like Fremont, his mapping expeditions will secure him lasting fame.

The third key figure is Charles Preuss, who is born in Germany in 1803, studies geodesy (the science associated with measuring the earth), and becomes a surveyor and mapmaker for the government of Prussia. He immigrates to America in 1834 and is hired on by Fremont for his science — to accurately measure longitudes and latitudes, temperatures and barometric pressures — and for his artistic talent, to create visually attractive maps.

Fremont rounds out his band with 21 others, mostly experienced French trappers who are familiar with the routes and are known by various native tribes and outpost proprietors along the way. Foraging for game will be crucial, so he hires an Illinois hunter named Maxwell. He also adds Randolph Benton, the twelve-year-old son of his powerful father-in-law senator, “for development of mind and body which such an expedition would give.”

Together they set out from St. Louis on May 22, 1842,, heading west 240 miles by steamboat along the bend of the Missouri River to Independence, where America’s two great early highways converge – the Santa Fe Trail drifting southward New Mexico and the Oregon Trail headed to Oregon in the north.

July 1842

The Party Reaches The Platte River In Early July

Once at Independence, Fremont further outfits the expedition with wagons, livestock, provisions, and scientific gear for the overland trip ahead.

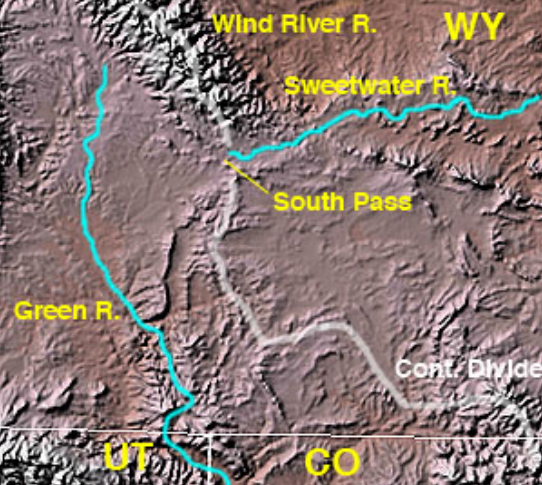

The goal for their trip is fairly modest in scope – to reach the South Pass break in the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and then turn around and come home with detailed maps and descriptions in hand.

They will follow the Oregon Trail, originally blazed by predecessors including the Native American tribes, Lewis and Clarke and Colter, Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, de Bonneville and others.

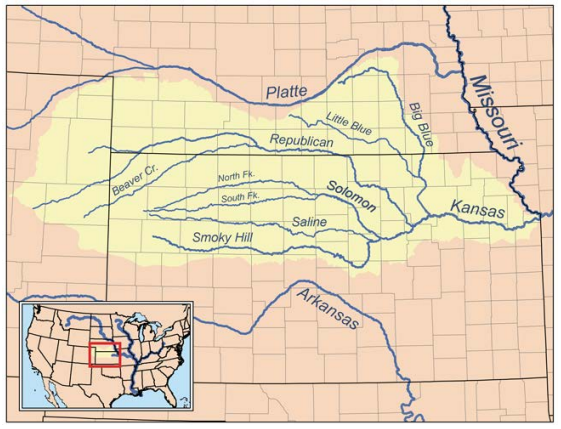

On June 10, they pick up the trail heading due west alongside the Kansas River. They arrive at the approximate future site of Lawrence, Kansas, on June 12, and Topeka on June 14. From there they turn north toward the Nebraska Territory, on a route that parallels the Big Blue River. On June 17, they mingle with a local Indian tribe. Fremont, who speaks French fluently, observes this moment in time.

A number of Kanzas Indians visited us today…(and) I found one sitting on the ground among the men, gravely and fluently speaking French…as any of my party, nearly all of French origin.”

They move up the Big Blue into the Nebraska Territory to the Platte River, making roughly 20 miles on an average day, and again shift west to the head of the Little Blue River, which they reach on June 22. Fremont captures their daily routine.

During the day…making astronomical observations…to lay down the country…(and) keep up our map regularly in the field.

Along with basic survey work comes detailed descriptions from the realm of earth sciences – plants and flowers, soil content and geologic formations, types of timber and grassland, species of animals.

The landscapes opening up before their eyes are breathtaking. On June 30 – in language that will later capture the imagination of the American public – Fremont describes his initial sighting of the Plain’s buffalo herds: June 30th.

First view of buffalo. The air was keen the next morning at sunrise, the thermometer standing at 44 degrees and it was sufficiently cold to make overcoats very comfortable. A few miles brought us into the midst of the buffalo swarming in immense numbers over the plains, where they had left scarcely a blade of grass standing. Mr. Preuss, who was sketching at a little distance in the rear, had at first noted them as large groves of timber.

In the sight of such a mass of life, the traveler feels a strange emotion of grandeur. We had heard from a distance a dull and confused murmuring, and when we came in view of their dark masses, there was not one among us who did not feel his heart beat quicker. It was the early part of the day when the herds are feeding, and everywhere they were in motion. Here and there a huge old bull was rolling in the grass and clouds of dust rose in the air from various parts of the bands, each the scene of some obstinate fight. Indians and buffalo make the poetry and life of the prairie and our camp was full of their exhilaration.

On July 1, Fremont further captures the spirit of adventure around a hunt for cow meat.

My horse was a trained hunter, famous in the West, under the name of Proveau… in a few minutes he brought me alongside the cow, and rising in my stirrups, I fired at a distance of a yard, the bullet entering at the termination of the long hair and passing near the heart…felling her.

July 2 brings the party to the branch of the Platte River, with the North branch some 2,250 feet wide and the South branch a mere 450 feet. The main party heads up the North artery, their destination being the fur trading outpost at the Laramie, in the Wyoming Territory.

August 1842

They Reach Their South Pass Destination

On July 9, excitement builds as their final destination finally comes into view.

This morning we caught the first faint glimpse of the Rocky Mountains, about sixty miles distant.

Their exuberance, however, is tempered by dwindling supplies, especially foodstuffs, where their diaries bemoan a lack of coffee, salt, sugar, bread, macaroni and cow meat in particular.

The taciturn map-maker, Charles Preuss, emerges as the chief grumbler among the crew, often critical of Fremont’s leadership, especially as it relates to what he considers foolish gambles.

It is ridiculous (of him) to risk lives to find the elevations of every mountain range.

At 4PM on July 13 the weary travelers arrive at the fur trading outpost at Laramie. The site is first developed in 1815 by a French trapper, Jacques La Ramee. It is converted into an actual fort in 1834 by the Kentucky native, William Sublette, who names it Fort William in his own honor. In 1841 John Jacob Astor’s firm buys the land and rechristens it Fort John. But all along it is referred to as the fort at the Laramie River — and thus it becomes Fort Laramie in 1849, after the U.S. Army buys it for $4,000 to support and protect settlers heading toward the gold fields of California.

By 1842, the structure itself has been modified from a modest 80 x 100 feet log enclosure to a much more expansive quadrangle, made of clay, with walls reaching 15 feet high, and reinforced inside by a square tower with rifle ports. On occasion it has been tested by local Sioux and Cheyenne raiding parties.

Their stay at Fort Laramie lasts for eight days, from July 13 to July 20. They use this time to rest up and refit their caravan for the winding 320 mile uphill climb toward the Rockies which lies ahead.

On July 21 they begin their ascent across the High Plains of Wyoming, heading northwest along the Platte, then swinging back southwest along the Sweetwater River toward the summit of the South Pass.

By July 28 they are one week into their trudge and encountering the effects of a severe drought. The ground is now covered daily by swarms of grasshoppers and other insects, which devour the grass needed for grazing. This depletes the buffalo herds, threatens the Plains Indian tribes with starvation, and raises the specter of hostile raiding parties. Some argue in favor of turning back, but Fremont brushes them aside and plunges onward.

On August 7 they reach the mouth of the Sweetwater River and on August 8 they are at their destination, the summit of the South Pass, where they are almost immediately greeted by “a severe storm of hail.”

When Fremont arrives there, the South Pass is less well known than its northern counterpart, the Lehmi Pass, which Lewis and Clark followed in their 1805 “water-route” sortie to the Pacific coast.

Both Passes are roughly 7,400 feet above sea level – or half the height of the typical Rocky Mountain range.

The South Pass is 35 miles wide. Those previously crossing it include the Astorian trapper, Robert Stuart, in 1811, the fur merchant, W.H. Ashley, in 1824, and the colorful army Captain, Benjamin Louis de Bonneville, born in Paris and a West Point graduate, who leads a 100 man train caravan through in 1832.

Once at his planned destination, Fremont is amazed by the grandeur that surrounds him at daybreak.

The scenery becomes hourly more scenic and grand…the sun has just shot above the wall, and makes a magical change. The whole valley is growing and bright, and all the mountain peaks are gleaming like silver…the pines on the mountain seem to give it much additional beauty.

While he reckons that the party has come 950 miles from the Kansas River, once Fremont views the Wind River Mountains to his north, he can’t resist the temptation to conquer them.

I left the valley a few miles from our encampment intending to penetrate the mountains as far as possible.

August 15 – October 17, 1842

Fremont Plants His American Flag On A Wind River Mountain Peak

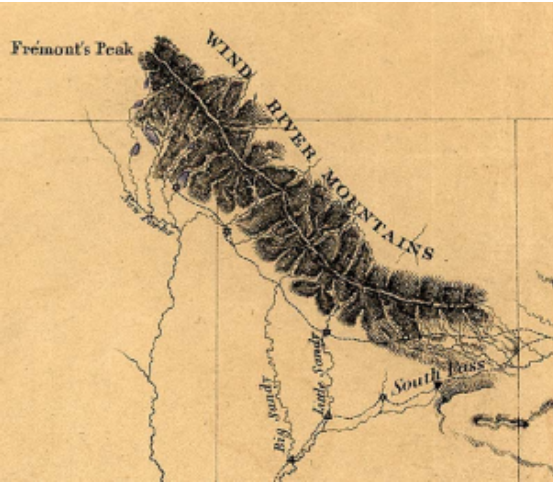

The Wind River Mountain slashes some 100 miles in a northwesterly fashion from the entrance to the South Pass.

The range is split down the middle by its portion of the Great Continental Divide, the series of mountains running the length of North and South America from the Bering Straits to the Strait of Magellan – with rivers to the west running to the Pacific Ocean and those to the east seeking the Atlantic.

On his ascent, Fremont encounters an idyllic lake.

Winding our way up a long ravine, we came unexpectedly in view of a most beautiful lake, set like a gem in the mountains. I have called it the Mountain Lake.

The natural beauty of the place draws him onward. On August 12 he writes:

Of all the strange places on…our long journey none left so vivid an impression on my mind as this place.

On August 13, he reflects on the “savage sublimity of the naked rock” all around him, and compares its “wildness” to the unbound, pioneering character of the American people.

It is not by the splendor of far off views, which have lent such a glory to the Alps, that these impress the mind; but by a gigantic disorder of enormous masses, and a savage sublimity of naked rock, in wonderful contrast with innumerable green spots of a rich floral beauty, shut up in their stern recesses. Their wildness seems well suited to the character of the people who inhabit the country.

His band finally settles on scaling a high promontory point they spot, about three-quarters of the way up the spine of the ridge. On August 15, 1842 they reach their objective and celebrate by planting a flag.

I sprang upon the summit, and another step would have precipitated me into an immense snow field 500 feet below. (Once there) we fixed a ramrod in a crevice (and) unfurled the national flag to wave in the breeze where never a flag waved before.

Thereafter this site will become known as Fremont’s Peak.

Having more than accomplished their duties, the band begins their two month journey back home. Fremont arrives in St. Louis on October 17, where he learns of a new challenge coming his way.