Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 32: The War Of 1812 Begins

March 1809 to September 1811

Britain And France Frustrate Madison’s Attempts To Stay Out Of War

Madison comes into office still believing that access to trade with America will be enough of a bargaining chip to avoid war and stop British and French interference with U.S. ships and sailors.

The Non-Intercourse Act of March 1, 1809, he inherits bans trade with both combatants – but also opens the door to resumption, should either nation declare its intent to end future aggression.

Over the next year, both will manipulate Madison and his diplomats into believing they are complying with America’s wishes.

The British take this tack immediately. On April 19, 1809, the British minister, David Erskine, tells Secretary of State Robert Smith that the Crown will no longer interfere with American ships at sea. Madison takes this at face value, and re-opens American trade with Britain.

On August 9, however, he learns that Erskine’s assurance to Smith was not “official” British policy, and so he reinstates the Non-Intercourse ban.

Ten months later, Napoleon steps up the heat on America in his March 23, 1810, Rambouillet Decree, saying that France will seize and sell all American ships it encounters.

The next move belongs to Madison. On May 1, 1810, he seeks reconciliation with both nations in passage of the so-called “Macon’s Number 2 Bill,” named after its sponsor, Nathaniel Macon, a House member from North Carolina.

This bill seeks a return to normalcy, re-opening trade with both France and Britain.

But with one caveat. Madison still wants public confirmation that interference with American ships has been “officially prohibited” – and he offers a “carrot” aimed at getting his way. Should either Britain or France openly announce a favorable change in policy, American will resume the trade embargo on its opponent.

Now it is Napoleon’s turn to manipulate Madison. On August 5, 1810, he instructs his foreign minister to tell the Americans that he will renounce future interference with shipping, if they will cut off trade with Britain. At the same time, he secretly orders the seizure of all American ships now in French harbors.

Madison naively takes Napoleon at his word, and, when three months pass without a corresponding message from Britain, he declares on November 2 that shipping to England will end, effective on March 2, 1811.

This enrages the British, who announce plans to step up their impressment activities and even blockade the port of New York.

May 1-16, 1811

Naval Battles Amplify War Fever

Two back-to-back naval clashes now increase tensions with Britain.

The first occurs in New York Bay, south of lower Manhattan.

On May 1, 1811, the frigate HMS Guerriere, with its 38 cannon and crew of 350 men, comes upon the USS Spitfire, a sloop sporting three guns and some 20 sailors, off Sandy Hook, New Jersey. The Spitfire is stopped and boarded, and an American-born seaman, sailing master John Diggio, is impressed.

The second incident, on May 16, involves bloodshed.

The American navy now has its guard up as the frigate USS President encounters what it erroneously believes to be HMS Guerriere off the coast of North Carolina. An exchange of fire follows, with the two sides disagreeing on who shot first. The British ship – which turns out to be the 18-gun sloop, HMS Little Belt – suffers 11 killed and 21 wounded in the battle.

Relations with Britain will never recover from these incidents.

Both occur at a time when U.S. Ambassador William Pinkney has already departed for a visit home, leaving a void in diplomatic relations in London.

At the same time, Napoleon continues to have his diplomats reassure a new U.S. Ambassador to France, Joel Barlow, about his peaceful intentions toward America.

November 7, 1811

British Backed Shawnee Tribe Defeated At The Battle Of Tippecanoe

In addition to the confrontations at sea, suspicions grow that British Canadians are building alliances with native tribes along the northern border to impede westward settlements.

Going all the way back to 1794, the burden for handling Indian affairs in the Northwest Territory has fallen on the shoulders of William Henry Harrison, son of the former Virginia Governor, Benjamin Harrison V.

His army career includes numerous battles on the frontier, and involvement in a series of negotiations leading to often forced cession of tribal lands to the United States.

In 1799, at age 26, he is elected to represent the Northwest Territory in the 7th U.S. Congress. His friend, Secretary of War, Thomas Pickering encourages John Adams to name him Governor of the Indiana Territory in 1801. Jefferson keeps him on because he seems willing to help the tribes learn agriculture and to become assimilated peacefully. Over time his land negotiations lead to adding millions of acres from Ohio to Wisconsin.

Some Of The Indian Land Cessions Negotiated By William Henry Harrison

| Year | Treaty of: | Main Tribes | Land Ceded to U.S. |

| 1795 | Greenville | 10 tribes together | 16.9 million acres, Ohio + strip west to Chicago |

| 1804 | Vincennes | Miami and Shawnee | 1.6 million acres in central Indiana |

| St. Louis | Fox and Sauk | 5.0 million acres in Wisconsin | |

| 1809 | Ft Wayne | Delaware and Miami | 3.0 million in eastern and western Indiana |

Of course the very notion of “owning land” remains foreign to the Indians – and resistance to these cessions builds as white settlers begin their occupation. In the Great Lakes region, it is the Shawnee Tribe that fights back most aggressively. They are led by the charismatic shaman, Tenskwatawa, called The Prophet, and his older brother, Tecumseh.

Tecumseh realizes that promises of support for native peoples from “the Great Father” in Washington always vanish when the time comes to deliver,

In July 1811, he begins to organize a confederation of tribes intent on driving the white men out and restoring the Indian traditions and way of life. In turn, they tell Harrison that the Ft. Waynecession is invalid, and that they intend to fight for the land.

They also signal that their cause is being supported by British allies in Canada.

To prepare for battle, Tecumseh gathers some 5,000 warriors on Miami land in Indiana, near the confluence of the Tippecanoe (“buffalo fish”) and Wabash Rivers. This site is called “Prophetstown” by Harrison, and he sets out with a force of 1,000 troops to conquer it, in September 1811.

On November 6, 1811, he encounter a tribal delegation near Prophetstown under a flag of truce. At the time, Tecumseh is in the southwest, attempting to recruit more support from the Cherokees. The two sides agree to meet again the next day.

Instead, at 4AM on November 7, the Indians initiate a surprise attack behind The Prophet on Harrison’s camp, huddled just east of Burnett Creek. The battle rages for two hours, with the American falling back initially, and suffering heavy casualties. But unlike Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa is more the religious leader than the warrior. So Harrison rallies his troops, breaks out of his initial trap and eventually burns Prophetstown to the ground.

This victory at Tippecanoe will insure national fame for William Henry Harrison as a frontiersman who has successfully defeated both the hostile tribes and their British allies.

The truth is much more modest than the legend. Actual losses for each side total only 100 fighters, and the outcome does little to divert Tecumseh and his band from continuing to attack white settlers in the region.

Another two years will pass before Tecumseh’s confederation is finally subdued for good, at the Battle of the Thames, Harrison’s true landmark victory.

1811-1813

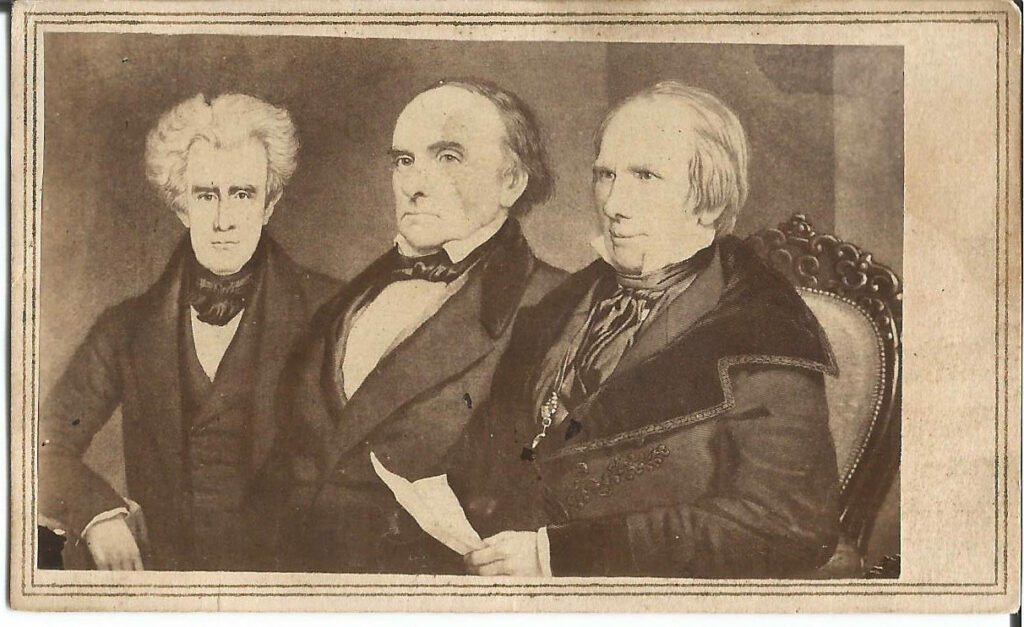

Three Political Giants Enter The U.S. House

The run-up to, and outbreak of, the War of 1812, witnesses the emergence of three politicians who will shape US foreign and domestic policy over the next four decades.

Henry Clay and John Calhoun enter politics as Democratic-Republicans, before later founding their own political parties in opposition to President Andrew Jackson. Calhoun starts up the “Nullifier” Party in 1828 and Clay begins his Whig Party in 1834.

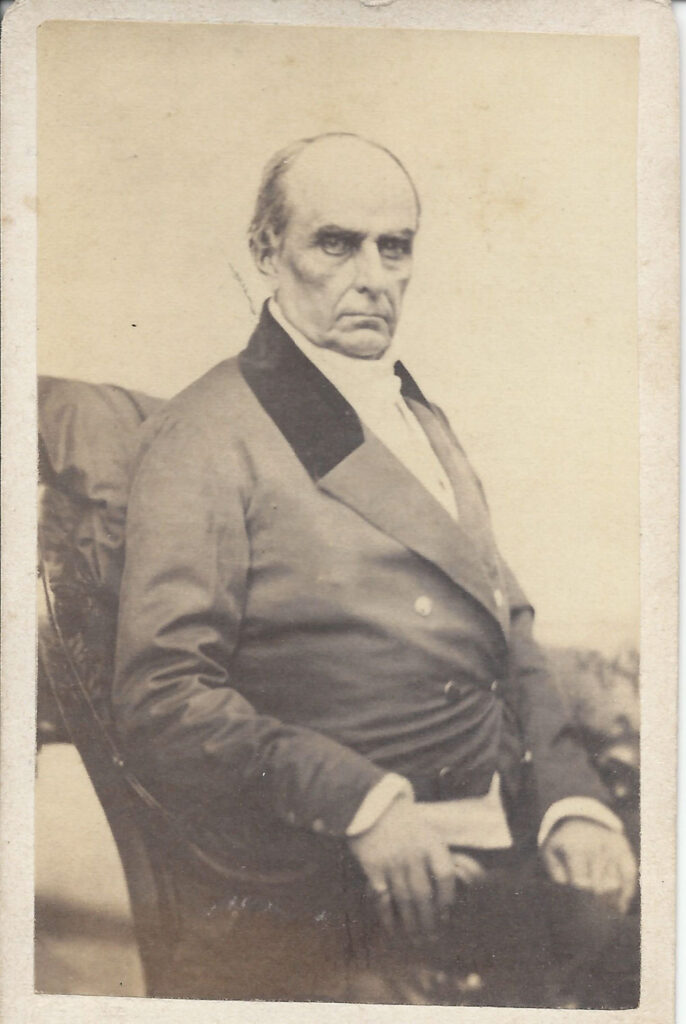

Daniel Webster is a rock-ribbed Federalist who eventually joins the Whigs, while moving back and forth between public office and his lucrative law practice.

Each man will become the leading spokesman for his region of the country – Webster for the Northeastern states, Calhoun for the South, and Clay for the new West.

All three play critical roles during the War of 1812 and later on as regional differences over slavery threaten to tear the Union apart – with Clay and Webster trying to hold it together and Calhoun eager to have his South secede.

Along the way they will also battle back and forth for the presidency, Clay running on five occasions, Webster on three and Calhoun twice. But each man’s long and often controversial track record in public office invariable leads to defeat.

Together they will earn their reputation as “the Great Triumphirate.”

June 4, 1812

Congress Declares War On Britain

Tensions with Britain continue to build after the two naval encounters in May and the Tippecanoe battle in November, 1811.

At this point Madison is being carried along by calls for war with Britain emanating from the public, the politicians and his generals.

His new Secretary of State, James Monroe – appointed April 2, 1811, after Robert Smith is ousted – is a former front line officer and combatant in the Revolutionary War, and ready to take on the British again.

He is joined by two new members of the House, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, who together rally a faction in Congress known as the “Warhawks.”

If Britain is not only threatening U.S. shipping, but also encouraging Indian resistance, then America surely needs to respond with force.

As always, when conflict with Britain arises, special attention is focused on Canada.

Many see the continued presence of the British along the northern border as “unfinished business” from the Revolutionary War. They inhibit the growth of America’s fur trading industry, provoke tribal resistance on the frontier, and present an invasion threat by garrisoning troops across forts along the border.

This threat becomes even more real throughout the winter and spring of 1812 by importation of British regulars and stepped-up recruiting of local militia across Canada.

On April 10, 1812, Congress also gives Madison authority to call up to 100,000 troops from state militias, should the need arise.

American and British diplomats attempt to search for peaceful ways out, but the sticking issue always comes back to impressments. Britain says that it must continue to retrieve its nationals serving on American ships in order to win its naval battles with the French. As much as Madison wants to believe that American commerce is worth more than impressed sailors, this is never the case with the British.

By now, public opinion has swung almost entirely away from the one policy espoused by every president from Washington through Madison – that of maintaining “neutrality in foreign conflicts” and avoiding what Jefferson called the non-productive costs associated with war.

War (is) but a suspension of useful works, and a return to a state of peace, a return to the progress of improvement

The only remaining opposition to war lies with the New England merchants, who regard the prospect as even more fatal to their business prospects than the Jefferson-Madison embargos.

Finally the time for compromise runs out. On June 1, 1812, acting in accord with the Constitution, Madison goes to Congress and asks them to declare war against Britain. His principal reasons why include: ongoing impressment of seamen; blockades against American shipping; confiscation of ships; and incitement of the Indian tribes in the Northwest territories.

The actual voting, however, is hardly unanimous. The House supports the war measure by 78-45; the Senate is much closer, with passage by only 18-13. The outcome is determined on June 4 along party lines – with no Federalists supporting the President.

Conjecture remains about exactly why the Democratic-Republicans – so viscerally anti-war by nature – come around in favor of taking on the powerful British once again. Perhaps the most likely explanation lies in the lingering wish to remove Britain from Canada once and for all. This and a belief that an inland war could be won easily and quickly, while America’s navy was now strong enough to hold its own against the British fleet, in battles close to home.

With passage of the bill, the War of 1812 is about to begin.

July 4, 1812

The Federalist Daniel Webster Attacks Madison’s Decision And Preparedness

New England looks for a powerful spokesperson against the war, and they find one in the Federalist, Daniel Webster, a 30 year old lawyer from New Hampshire, who is on his way to becoming a major political figure in Washington over the next four decades.

On July 4, 1812, in a speech to the Washington Benevolent Society, Webster assails the President for leaping blindly into a very dangerous war the nation is ill prepared to fight.

In what will become his usual dramatic fashion, the speech begins by citing the seriousness of the hour, the wisdom of Washington in regard to avoiding warfare, and the woeful lack of preparation for battle.

In an hour big with events of no ordinary impact we meet. We come to take counsel of the dead…to listen to the dictates of departed wisdom. We are in open war with the greatest maritime power on earth. This is a condition not to be trifled with.

Washington embraced competent measures of defence, yet it was his purpose to avoid war. Would to God that the spirit of his administration might actuate this government.

With respect to the war, resistance and insurrection can form no part of our creed. The disciples of Washington are neither tyrants in power, nor rebels without. We are yet at liberty to lament the commencement of the present contest.

We believe that the war is premature and inexpedient. Our shores are unprotected; our towns exposed. It exceeds belief that a nation thus circumstanced should be plunged into sudden war.

He cites the damage to the US economy likely to follow from the conflict.

The voice of the whole mercantile interest is united against the war. We believe that it will endanger our rights, prejudice our best interests.

Also that, in opposing Britain, America would be strengthening Napoleon’s forces, which might soon be redirected against America.

Nor can we shut our eyes to the prospect of a French alliance. That we should make common cause and assist her to subdue her adversary and to extend her chains and despotism over the civilized world seems to be a dreadful departure from true wisdom and honest politics. French brotherhood is an idea big with horror and abomination. What people hath come within the grasp of her power and not been ground to powder?

He closes by calling upon the sons of New England to stand up against support for war and for France.

But if it be in the righteous counsel of heaven to bury New England, her religion, her governments, and her laws under the tyranny of foreign despotism, there are those among her sons who will never see that moment.

They cannot perish better than standing between their country and the embrace of a ferocious tyranny. At the appointed hour, they shall, for the last time, behold the light of the sun not with the eyes of slaves or as subjects of an imperious despotism.

Indeed, time will show that while Madison believes an easy victory will follow, he has failed woefully to prepare a military force sufficient to carry the day.

The U.S. Army numbers only 12,000 Regulars; so much of the fighting will depend on often poorly trained state militias. The U.S. has the largest “neutral” fleet in the world, but it will be no match for the Royal Navy. And since Congress has shut down the US Bank, his access to funding the war is constrained.

Fortunately for Madison, the British are similarly ill-equipped to fight.

In June 1812 the bulk of their ground forces are attacking the French in Spain, under the future Duke of Wellington. Only 6,000 red coats have been left behind in North America to defend various Canadian forts. Likewise the British navy has its hands full trying to enforce the blockade of cargoes flowing into France.

July 12 – August 16, 1812

The War In Western Canada Begins Badly

As in 1775 war with Britain, America assumes that a quick strike into Canada will succeed, and perhaps even cause the British to back away from further fighting. As Jefferson says:

The acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching.

So the battle begins, with the opening gambits along the western edge of Lake Erie and north into Lake Huron.

Things immediately go badly for the US forces.

On July 17 a contingent of 200-300 British and Indian warriors land on Mackinac Island and surprise Lt. Porter Hanks and the American troops garrisoned at Ft. Michilimackinac – who surrender post haste on the belief that they are badly outnumbered. Soon after two U.S. sloops are also taken when they come into port believing that the fort is still in friendly hands. Porter is subsequently court-marshalled for cowardice, but is killed by a British shell while still under arrest.

Command of the “Army of the Northwest” lies with Brigadier General William Hull, a Revolutionary War veteran praised by Washington, and presently Governor of the Michigan Territory. But Hull is 59 years old, and has tried, unsuccessfully, to avoid the “offer” from Secretary of War Eustis to return to combat.

When Hull learns of the Mackinac Island debacle, he fears that Ft. Dearborn in Chicago may also be attacked and overrun. He orders the immediate evacuation of the fort. On August 15, some 66 soldiers and 27 women and children evacuate under a flag of truce, only to be set upon by Potawatomi warriors who kill over half of the Americans and capture the rest.

While these two reversals are occurring, General Hull and 2,500 troops are preparing to invade Canada along the western edge of Lake Erie. On July 5, 1812, Hulls sets up camp at Ft. Detroit. One week later he crosses the Detroit River, and issues a proclamation meant to scare his opponents into submission:

INHABITANTS OF CANADA: After thirty years of peace and prosperity, the United States have been driven to arms. The injuries and aggressions, the insults and indignities of Great Britain have once more left no alternative but manly resistance or unconditional submission. The army under my command has invaded your country. The standard of the union now waves over the territory of Canada. To the peaceful and unoffending inhabitants it brings neither danger nor difficulty. I come to find enemies, not to make them; I come to protect not to injure you …I have a force which will break down all opposition, and that force is but the vanguard of a much greater. If, contrary to your own interest, and the just expectations of my country, you should take part in the approaching contest, you will be considered and treated as enemies, and the horrors and calamities of war will stalk you.

Once on Canadian soils, Hull sends our various probes that encounter resistance from a mixture of British regulars, local militia and various tribesmen, notably Tecumseh.

By August 9, the set-backs convince Hull that he cannot advance into Canada without more troops and cannon, and he retreats back over the river to Ft. Detroit.

By now, however, the British are ready to go on the offensive and chase him. They assemble a force of some 300 Regulars, 400 militia and 600 Indians at the Canadian town of Amherstburg, then head out after Hull and his remaining 2200 men at Detroit.

The red-coat commander, Major General Isaac Brock, decides to bluff Hull into believing he is surrounded by overwhelming opposition. His dispatch to Hull also raises the specter of uncontrollable slaughter waged by his tribal bands:

The force at my disposal authorizes me to require of you the immediate surrender of Fort Detroit. It is far from my intention to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware, that the numerous bodies of Indians, who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences…

On August 15, Brock fires on the fort, using the few cannon at his disposal, along with support from two Royal Navy sloops on the nearby river. One day later he follows up with demonstrations, led by Indian war whoops intended to spook the Americans.

These succeed immediately. Hull has his daughter and grandchild in the fort, and fears repeat of the slaughter at Ft. Dearborn. He asks Brock for three days to arrange for surrender; Brock gives him three hours.

When news of the capitulation at Detroit reaches Washington, Hull is arrested and his command is handed to William Henry Harrison. A subsequent court martial sentences Hull to death, but his sentence is commuted by Madison, in light of his long service during the Revolution and his advanced age.

All of these setbacks – Mackinac, Ft. Dearborn, Detroit – occur as the two parties pick their candidates for the election of 1812.

1806-1852

Sidebar: Profiles Of The “Great Triumphrate”

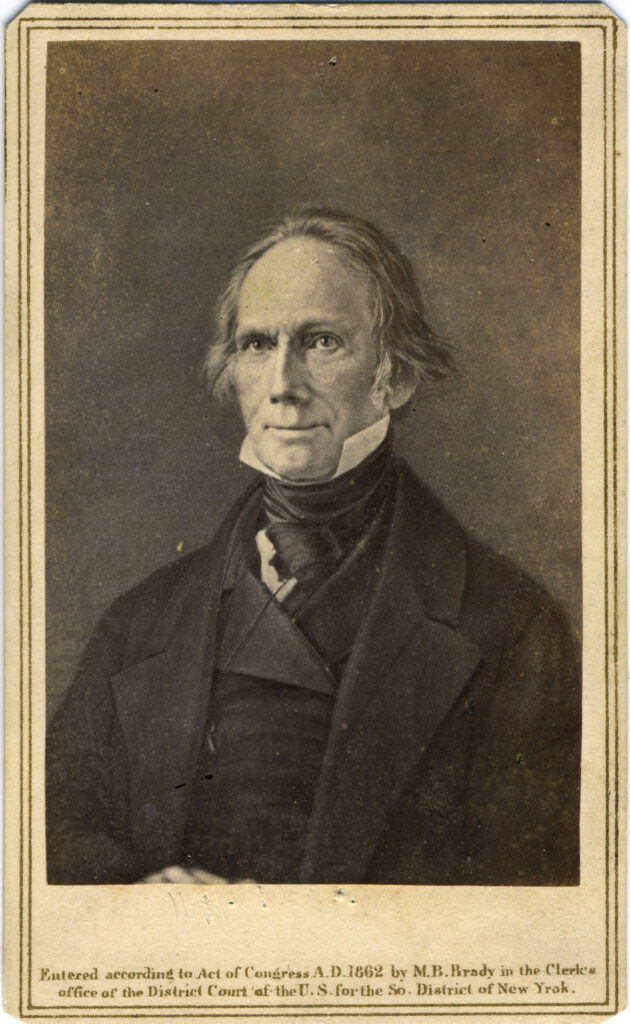

Henry Clay Of Kentucky (1777-1852)

After serving two brief stints in the U.S. Senate, Henry Clay decides that the House, with its “power over the purse,” is where he belongs. In 1811, at age 33 years, he is elected to the lower chamber. On his first day there, March 4, 1811, he is chosen as Speaker by a 75-38 margin, a signal recognition of his intellect and his ability to find middle ground between his Democratic-Republicans and the Federalist opposition. He will serve his country in Washington over a 46 year span, until his death.

Clay is born on April 12, 1777, in eastern Virginia, where his family has lived for 150 years. His first home is a modest-sized plantation, with 25 slaves, situated in Hanover County, near a swampy area known as The Slashes. When Henry is 14 years old, his family moves west to Kentucky, leaving him behind to find his way in the world. He moves to Richmond, where he first works in an emporium and then lands a job clerking at the state’s high court chancery.

Clay’s formal education is minimal, but he is intensely curious about the world, naturally gregarious, and meticulous, especially when it comes to his handwriting. This latter trait recommends him to Judge George Wythe, who suffers from a crippled hand and is looking for a private secretary. Clay lands the job and stays with the Judge over a four year period.

Wythe has signed the Declaration of Independence, and become a classical scholar at the College of William & Mary, where he mentors a host of political leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe. He transforms Clay, intellectually, socially and inspirationally, during their four years together, and prepares him for a planned career in law. He also advises Clay on slavery, touting the idea that education must accompany freedom, if the problem is to be solved. Clay’s posture on the dilemma tends to mirror Jefferson’s. On one hand he decries it as an evil practice all his life:

Can any humane man be happy and contented when he sees nearly thirty thousand of his fellow beings ‘around him, deprived of all rights which make life desirable, transferred like cattle from the possession of ‘one to another…when he hears the piercing cries of husbands separated from wives and children and parents. ‘The answer is no…

But he too will continue to buy and own slaves up to his death, when he finally embraces Wythe’s solution – granting emancipation and supporting education and employment for those freed.

In 1797 Clay passes the bar, heads west to visit his family, and settles down in the well established town of Lexington. Once there, his law practice, both civil and criminal, takes off, as does his lasting reputation as Shakespeare’s “Prince Hal,” a good fellow, well met, ready to drink, gamble on cards and horses, and share his opinions with all comers. In 1799 he marries Lucretia Hart, adding both wealth and slaves in the process. He joins the law faculty at Transylvania College, and enters politics in 1803, winning a seat in the Kentucky State Assembly that he will hold for six more years.

In 1806 his national notoriety grows by successfully defending Aaron Burr against charges of treason filed by the U.S. District Attorney in Kentucky.

Ill will over this support for Burr accounts in part for the first of two non-fatal duels Clay will instigate during his career. On January 19, 1809, he exchanges three shots with another legislator, Humphrey Marshall, leaving both men with slight wounds.

Within Democratic-Republican circles, he is known as the “Rising Star of the West.”

As a leader of the “War Hawk” faction, he supports Madison’s call to war with Britain in 1812.

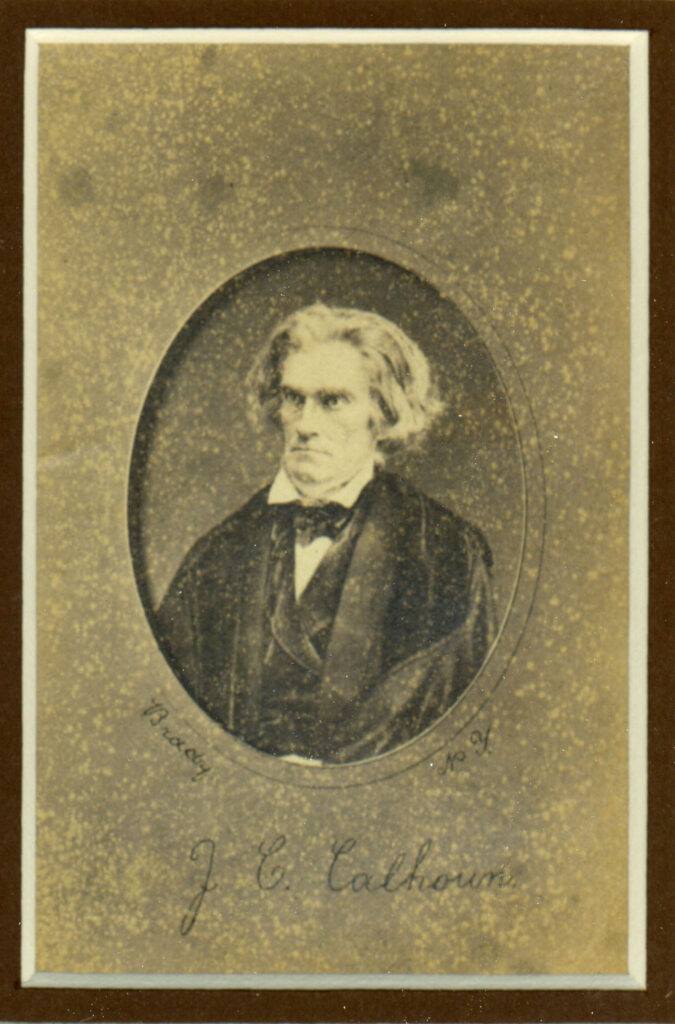

John C. Calhoun Of South Carolina (1782-1850)

If Clay brings a western perspective to Congress, John Calhoun will become a leading spokesperson for the more conservative partisans of the south, across his four decades in office.

He is born on March 18, 1782 in Abbeville, South Carolina, a frontier settlement in the northwest corner of the state, abutting Georgia. His ancestors are Scots-Irish immigrants, who put down roots in Long Cane, some thirteen miles to the south, before being driven out by hostile Cherokees. His father, Patrick Calhoun, Jr., a survivor of the Cherokee’s Long Cane massacre of 1760, builds a cotton plantation, worked by his family and 30 slaves. Patrick is also active in the state legislature, and known for strong anti-Federalist positions.

John Calhoun is raised as a Presbyterian, with its Calvinistic emphasis on hard work, personal discipline, stern demeanor, and a rather bleak view of human nature. He is frail as a youth, and drawn early on to academics rather than farming. His early formal education is limited, but his parents recognize his bent, and enroll him at Yale University in the fall of 1802. While there, his Calvinist traditions come up against early strains of Unitarianism, with its emphasis on beliefs born of rational, independent thought.

He graduates from Yale in 1804 and soon moves on to Litchfield Law School in Connecticut, run by its founder, one Tapping Read, whose students include both Calhoun and Aaron Burr. Ironically, Read is an outspoken supporter of a strong national government, something his two famous graduates come to question.

In 1807, Calhoun is back in South Carolina and practicing law, when the British frigate HMS Leopold attacks the US Chesapeake off the Virginia coast and impresses four of her sailors. Calhoun organizes a protest meeting held at the Abbeville courthouse, and delivers a stirring speech in favor of an embargo against Britain and stepped up preparations for war. This entry into the political arena leads to two terms of service in the South Carolina state legislature.

At this time he is also falling in love with his first cousin once removed, Floride Boneau Colhoun, later famous for her outspoken moral rectitude in the 1830 “Petticoat Affair.” The strait-laced suitor is uncharacteristically affective in his pursuit of Floride:

My dearest one, may our love strengthen with each returning day, may it ripen and mellow with our years, and may it end in immortal joys. … May God preserve you. Adieu my love; my heart’s delight, I am your true lover.

The two marry and move into her 1100 acre Fort Hill Plantation, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, as Calhoun is about to become a political fixture in Washington. He arrives there soon after the Twelfth Congress convenes on November 4, 1811. Like most congressmen of the time, he resides is a boardinghouse, his named “the War Mess” and shared with his new colleague and ally, Henry Clay of Kentucky.

His administrative skills are immediately apparent to all, as is his willpower. He is appointed in the House to the Foreign Affairs Committee and soon becomes its chair. On June 3, 1812, he sums up the feelings of his fellow committee members toward the recent British aggression:

The mad ambition, the lust of power, and commercial avarice of Great Britain, arrogating to herself the complete dominion of the Ocean, and exercising over it an unbounded and lawless tyranny, have left to Neutral Nations—an alternative only, between the base surrender of their rights, and a manly vindication of them… (The committee) feels no hesitation in advising resistance by force—In which the Americans of the present day will prove to the enemy and to the World, that we have not only inherited that liberty which our Fathers gave, us, but also the will & power to maintain it.

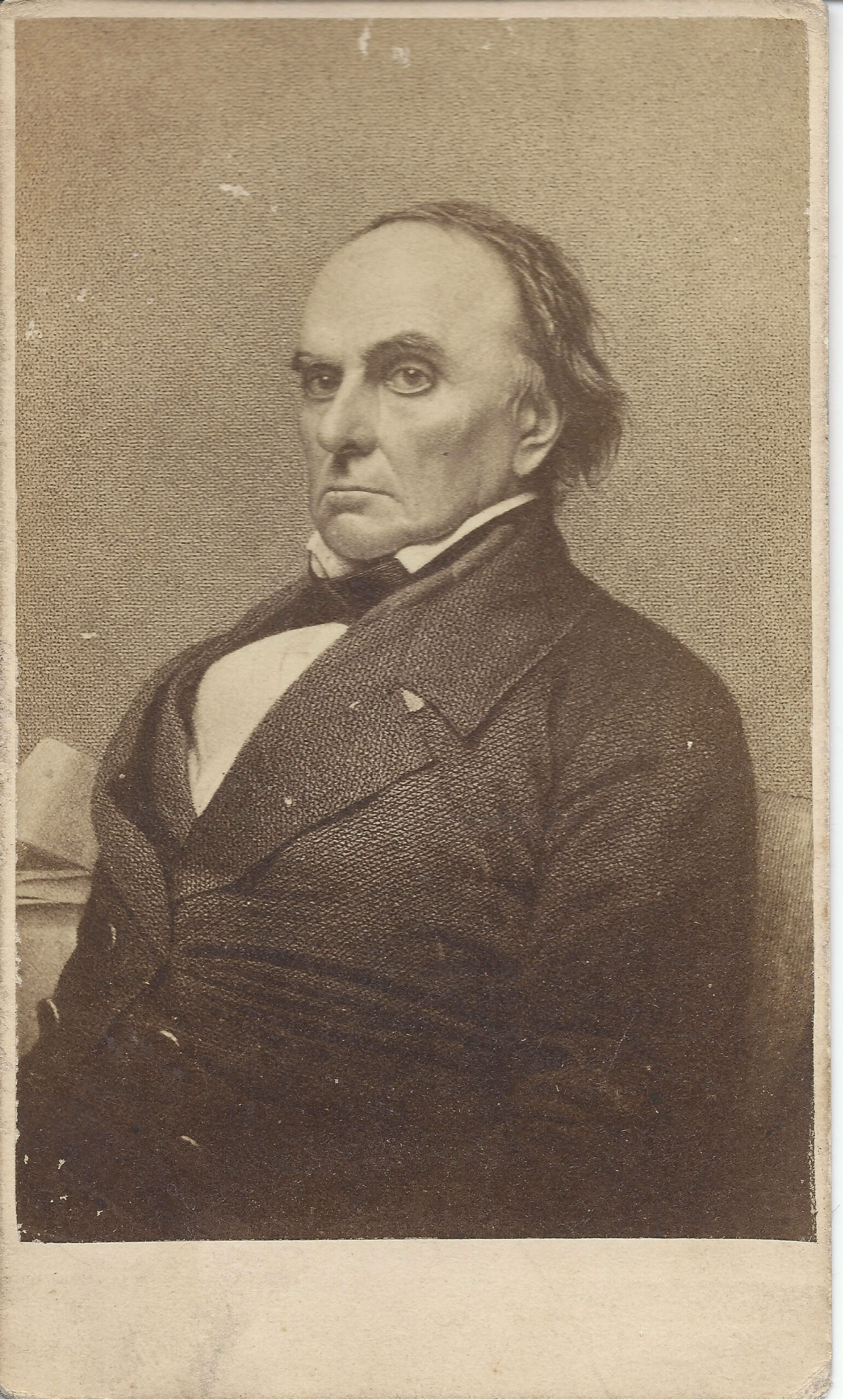

Daniel Webster Of Massachusetts (1782-1852)

The third member of the triumvirate who assume political leadership from 1810 to 1850 is Daniel Webster, whose famous oratory captures the sentiments of the elite Federalist establishment in New England.

Webster’s antecedents emigrate from Scotland to New Hampshire in 1637. His father, Ebenezer, fights in the French & Indian War and in 1761 carves out a 225 acre farm on the western frontier in the town of Salisbury. In 1775 he organizes the Salisbury Militia and leads it throughout the Revolutionary War. Back home, Eben serves in the New Hampshire state legislature and as an elder in the Congregational Church.

Daniel Webster is born on January 18, 1782, Eben’s fourth child. The boy adores his father, who tells him tales of the patriotic war, reads to him from the Bible and encourages his class for want of Latin. One year later he has risen to the top rank, before being called back to Salisbury to begin working as a teacher.

He escapes this fate with the help of a local minister, Thomas Thompson, in nearby Boscawen, who agrees to tutor him for one dollar a week. In 1797 he enrolls at Dartmouth College. Once there, Webster comes fully into his own. His self-confidence grows – some would say into arrogance – and he uses his powerful memory and love of words to become a dominant public speaker and debater. Classmates label him their “ablest man.”

After graduating, he is prodded into pursuing a legal career by his father. Webster himself sees the profession as filled with cunning and hypocrisy and says “I pray to God to fortify me against its temptations.”

But his feelings change in 1804 when he goes to work in Boston for Christopher Gore, ex-Attorney General of Massachusetts, who has made a fortune in financial speculation around Revolutionary War bonds, and in representing dispossessed Loyalists (to the Crown) in property disputes. Webster regards Gore as a genuine legal scholar to be emulated, and Gore encourages the youth to stick with the law and aim high in his career.

In 1805 Webster passes the bar and opens a law practice in Boscawen. His talents as a trial lawyer are soon evident to all, and his annual income soars to over $2,000 a year.

The courtroom becomes his stage, a place to show off both forensic logic and a love of language, accumulated over years of reading and memorizing doses of the Bible and Shakespeare and John Milton. One of his legal adversaries admires his innate theatrical talents:

There never was such an actor lost to the stage as he would have made, had he turned his talent in that direction.

His legal successes and oratorical skills soon draw Daniel Webster into the political arena, despite his warning in an 1809 Phi Beta Kappa address at Dartmouth:

The main impediments to moral improvements are love of gold and pursuit of politics.

His father’s stories of the revolution make him first and foremost a Union man – and his emotionally charged pleadings to preserve the “great experiment of 1776” will form his lasting legacy.

But politically he is a staunch Federalist. His faith lies in the Constitution, in a strong national government and in visionary leaders like George Washington. In an 1812 convention held by New Hampshire Federalists in Rockingham county, he assails Jeffersonian democracy.

The path to despotism leads through the mire and dirt of uncontrolled democracy.

He also, prophetically, announces another potential path to doom, this time related to secession.

If a separation of the states shall ever take place, it will be, on some occasion, when one portion of the country undertakes to control, to regulate, and to sacrifice the interest of another.

It is finally the impending war with Britain War that draws Webster onto the political stage. He is elected in 1812, at age thirty, to represent New Hampshire in the U.S. House.

Once in Washington, he boards with two influential senators, his former mentor, Christopher Gore, and Rufus King of New York.

Unlike Clay and Calhoun, Daniel Webster will be a sharp critic of Madison’s preparations for and management of the War of 1812.