Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 168: Free Black Leaders Make Their Voices Heard

May 28, 1851

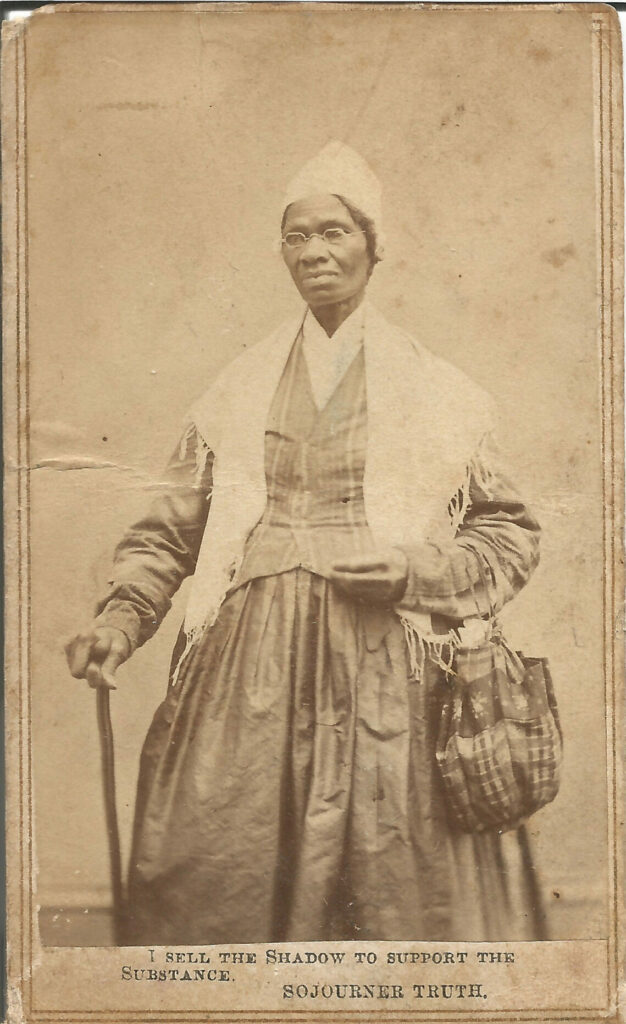

Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I A Woman” Address Pleads For Justice

The renewed terror associated with the wanton pursuit of blacks up north provokes more pleas for fairness and mercy from various free black leaders. Their pleas mirror those of men like David Walker in 1829 and Henry Highland Garnet in 1843.

One of them this time is a woman who adopts the name Sojourner Truth.

Like Frederick Douglas, she has become a well-known public speaker by 1850 for the American Anti-Slavery Society, thanks to her association with Lloyd Garrison and his publication of her biographical Narrative. It begins with her birth as Isabella Baumfree in upstate New York in 1797 and recounts her being auctioned off to four different masters before escaping to freedom with one of her five children in 1826. She migrates to New York City and works as a housekeeper at a charity for the poor prior to experiencing a religious conversion in 1843, becoming a Methodist, adopting her new name, and setting off on her personal crusade to abolish slavery. As she says, “the Spirit calls me and I must go.”

As her fame spreads, she is also enlisted in the feminist cause, and on May 28, 1851, she attends a Woman’s Rights Convention held in Akron, Ohio, hosted by Frances Gage, an early leader in the suffragette movement. Since she can neither read nor write, her remarks are extemporaneous, as always. They are also surrounded by some after-the-fact controversy since not recorded verbatim and are only available through the recollection of two attendees whose accounts of the character, if not the content of her speech, differ substantially. In one version, Truth speaks in traditional English and in low key fashion. In the other, constructed twelve years after the fact by Frances Gage, her words are cast in the colloquial voice of a southern slave and laced with passion. While parts of the latter are suspect, it becomes the favored text over time for capturing her authenticity and wisdom in dramatic fashion.

As with Douglass, audiences are immediately moved by her commanding figure and dignified manner on stage and then, in her case, by an unexpected and disarming sense of humor. Thus in Akron, she opens her talk by warning white men of the “fix” they will be in once “de women” join forces to end slavery and secure their own rights.

Well, chillen, what dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’kilter. I tink dat ‘twixt de [negroes] of de South and de women at de Norf, all a-talking ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon.

From there she proceeds to put down one stereotype after another about the “fragile female,” proclaiming her history of laboring like a man, eating like a man, even bearing the lash like a man – not to mention suffering the physical pains of childbirth (five times in reality) along with the emotional grief of losing one to illness and seeing another sold off.

Throughout this litany, she punctuates her comments with the soon-to-be famous refrain, “and ain’t I a woman?”

But what’s all this here talking ’bout? Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to have de best place eberywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place — “and ain’t I a woman?

Look at me. Look at my arm, I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me–and ain’t I a woman?

I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it) and bear de lash as well–and ain’t I a woman?

I have borne thirteen children, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard–and ain’t I a woman?

Apparently challenged by someone in the audience as to the intellectual capacities of women and negroes, she scoffs this off as a mean inquiry, having nothing to do with basic rights as human beings.

Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head. What dis dey call it, Intellect? Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do with woman’s rights or [negroes’] rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Finally she takes on another familiar masculine assertion — namely that Christ’s gender proves that God intended women to be subservient with fewer rights than men. She dismisses this with the rejoinder that Christ was born of the miraculous union of God and Mary, and therefore “man had nothing to do with it!”

Den dat little man in black dar, he say woman can’t have as much rights as man, ’cause Christ wa’n’n’t a woman. Whar did your Christ come from?Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had not’ing to do with Him.

Within these simple observations, Sojourner establishes the truth as she knows it. From her powerless roots she has achieved power, and if she, a black slave, can do it, so can the other women in her audience.

She closes with a call to action, referencing Eve, “the fust woman God ever made” who was able to “turn the world upside down.” So it’s now up to the women in the room to “git it right side up again.”

If Eve, de fust woman God ever made, was strong enough to turn de world upside down all her one lone, all dese togeder ought to be able to turn it back, and git it right side up again, and now dey is asking to, de men better let ’em.

Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner ha’n’t got nothing more to say.

Regardless of any embellishments made by Frances Gage, both Sojourner Truth and her “Ain’t I A Woman” speech become pivotal to the history of the Women’s Rights movement. Truth herself will live on for over three more decades, helping to recruit black troops for the Union army, working for the Freedman’s Relief Association, meeting Lincoln and Grant, and continuing both her speaking engagements and her religious commitments. She dies in 1883 in Battle Creek, Michigan.

July 5, 1852

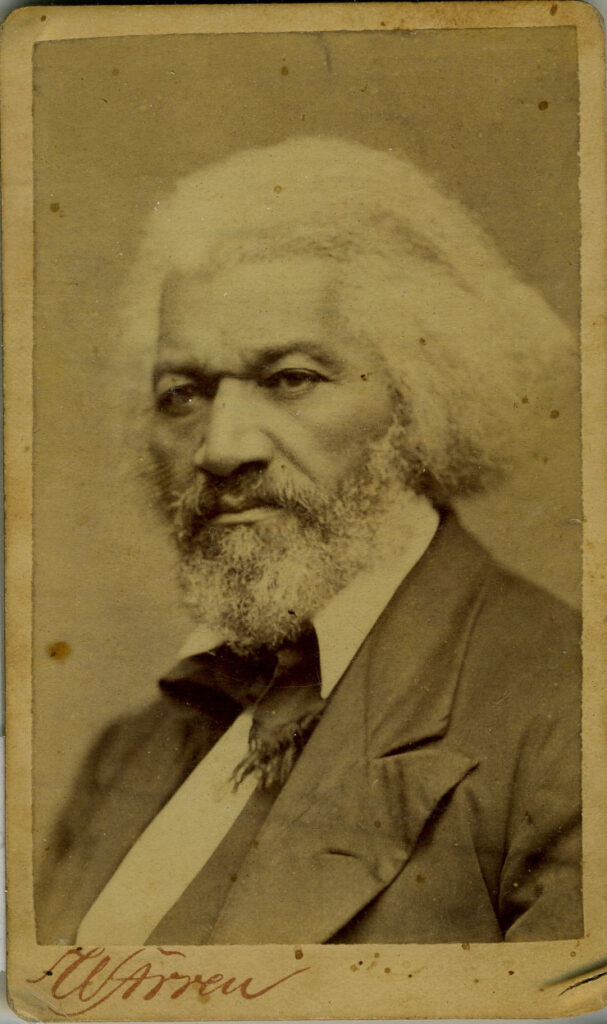

Fred Douglass Delivers His Famous Speech: The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro

As America is celebrating Independence Day of 1852, Frederick Douglass seizes the opportunity to deliver one more lecture to white America about the ongoing national sin of slavery.

Since passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, the public spotlight has shown on the famous Boston runaway cases – the Crafts in December, 1850, Minkins in February 1851, Sims in April 1851 – and on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best seller, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, finally published in book form in March 1852. Interspersed with these events is a steady backlash from Southern writers now coalescing around the “slavery as a positive good” rationale.

By 1852, Fred Douglass has broken with Lloyd Garrison, much to the chagrin of his former mentor.

The impetus seems to center on Douglass’ growing conviction that Garrison’s strategy for ending slavery will never succeed, for two reasons: first, by refusing to seek political support for emancipation in Congress; second, by ruling out all forms of violent protests to seek more rapid change.

In response, Douglass moves into the “political camp” alongside Gerritt Smith, James Birney, and the fledgling Liberty Party. He brings with him his newspaper, The North Star, and his star power on the lecture tour. With monetary support from Smith, he sponsors several new initiatives, including the National Black Council and the Black Manual Training School.

Finally an aggrieved Garrison decides to respond, calling his former protégé “an artful and unscrupulous schismatic.” This leads Harriet Beecher Stowe to intervene and restore a sense of peace between the two men.

But peace is the last thing on Douglass’ mind in July 1852, when he delivers what many consider his greatest public address, The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro.

The speech is delivered on July 5, 1852, at the Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, where Douglass resides. It is sponsored by the “Ladies of the Rochester Anti-Slavery Sewing Society,” and draws a crowd of some 500 attendees, each paying twelve and one half cents for the event.

While more measured in tone, the Douglass speech has all the emotional power of David Walker’s 1829 Appeal and Henry Highland Garnet’s 1843 Address to the Slaves of the United States.

Its message is a simple plea to white America to recognize the shared humanity of black men and women and, in so doing, to end the immorality and suffering caused by slavery and racism.

Douglass Begins Provocatively By Asking Why He Was Chosen To Speak

The speech itself is very lengthy and proceeds in stages like a legal brief.

It opens with Douglass offering a preamble that acknowledges the remarkable courage and patriotism underpinning the Fourth of July Day celebrations. In the face of abuses by their British parent, the colonists found justice in rebellion. The result was glorious freedom, worthy of remembrance.

The Fourth of July…is the birth day of your National Independence, and of your political freedom…The fathers of this republic…preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression…With them, justice, liberty and humanity were “final”; not slavery and oppression….Fellow Citizens, your fathers…succeeded; and to-day you reap the fruits of their success…. Of this fundamental work, this day is the anniversary. Our eyes are met with demonstrations of joyous enthusiasm. Banners and pennants wave exultingly on the breeze.

But then he shifts suddenly to the present, and startles his largely white audience by asking why they have chosen him, a Negro, to speak about the Fourth of July – when it is their day of celebration, not his.

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? …Do you mean to mock me, by asking me to speak? I (ask) with a sad sense of the disparity between us (for) I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary!… This Fourth July is yours, not mine….Above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.

He answers his own question by concluding that his presence must reflect a wish by the attendees – addressed with unrelenting irony as “fellow citizens” – to hear how the slaves feel about Independence Day. He promises to explain this using “the severest language” he can command.

My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is American slavery…(and to) see this day and its popular characteristics from the slave’s point of view…. I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery-the great sin and shame of America! “I will not equivocate; I will not excuse”; I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice…shall not confess to be right and just.

He Asks His Audience To Recognize “The Equal Manhood Of The Negro Race”

He wonders how white people can still be “blinded by prejudice” against blacks when they are exposed daily to the shared commonalities between the races played out around them day after day. Surely the evidence shows the “equal manhood of the Negro race.”

(In) affirm(ing) the equal manhood of the Negro race… is it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting, and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, silver and gold; that, while we are reading, writing and ciphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries, having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators and teachers; that, while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific, feeding sheep and cattle on the hill-side, living, moving, acting, thinking, planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all, confessing and worshipping the Christian’s God, and looking hopefully for life and immortality beyond the grave, we are called upon to prove that we are men!

Once conceding that the Negro is a man, denying his right to “own his own body” becomes “ridiculous.”

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? that he is the rightful owner of his own body?… To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your understanding.-There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.

Equally indefensible are the abuses suffered by those who are enslaved.

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employment for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.

Looking out on his audience, he asks again “what remains to be argued?” Instead of rhetoric, what America needs is “the whirlwind” to reveal the “hypocrisy” and “crimes against God” inherent in slavery.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

He concludes this section by cycling back to the Fourth of July – a day of celebration for whites, a reminder of “gross injustice and cruelty” for those enslaved.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.

Emotions Spill Out As He Paints The Picture Of Slavery

In the most emotional part of the address, Frederick Douglass tries to bring to life the realities of what slaves are forced to endure, for those in the hall. In these few sentences, he becomes “the whirlwind” made manifest.

Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade, the American slave-trade, sustained by American politics and American religion. Here you will see men and women reared like swine for the market.

Mark the sad procession, as it moves wearily along, and the inhuman wretch who drives them. Hear his savage yells and his blood-curdling oaths, as he hurries on his affrighted captives!

There, see the old man with locks thinned and gray. Cast one glance, if you please, upon that young mother, whose shoulders are bare to the scorching sun, her briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms. See, too, that girl of thirteen, weeping, yes! weeping, as she thinks of the mother from whom she has been torn!

The drove moves tardily. Heat and sorrow have nearly consumed their strength; suddenly you hear a quick snap, like the discharge of a rifle; the fetters clank, and the chain rattles simultaneously; your ears are saluted with a scream, that seems to have torn its way to the centre of your soul The crack you heard was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on.

Follow this drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slave buyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude.

Tell me, citizens, where, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.

In the solitude of my spirit I see clouds of dust raised on the highways of the South; I see the bleeding footsteps; I hear the doleful wail of fettered humanity on the way to the slave-markets, where the victims are to be sold like horses, sheep, and swine, knocked off to the highest bidder. There I see the tenderest ties ruthlessly broken, to gratify the lust, caprice and rapacity of the buyers and sellers of men. My soul sickens at the sight.

Douglass Turns His Fury On Congress And America’s Churches

He asks who is to blame for these abominations – and begins with the passage of the “shameless” Fugitive Slave Act in congress.

By an act of the American Congress, not yet two years old, slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form. By that act, Mason and Dixon’s line has been obliterated; New York has become as Virginia; and the power to hold, hunt, and sell men, women and children, as slaves, remains no longer a mere state institution, but is now an institution of the whole United States….In glaring violation of justice, in shameless disregard of the forms of administering law, in cunning arrangement to entrap the defenceless, and in diabolical intent this Fugitive Slave Law stands alone in the annals of tyrannical legislation.

America’s churches and clergy are also complicit in their “wickedly indifference” to slavery.

I take this law to be one of the grossest infringements of Christian Liberty, and, if the churches and ministers of our country were nor stupidly blind, or most wickedly indifferent, they, too, would so regard it…At the very moment that they are thanking God for the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, and for the right to worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences, they are utterly silent in respect to a law which robs religion of its chief significance and makes it utterly worthless to a world lying in wickedness.

Worse yet are the various theologians who teach that slavery is sanctioned in the Bible, a “horrible blasphemy” that serves to perpetuate evil.

But the church of this country is not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, it actually takes sides with the oppressors. It has made itself the bulwark of American slavery, and the shield of American slave-hunters. Many of its most eloquent Divines…have shamelessly given the sanction of religion and the Bible to the whole slave system. They have taught that man may, properly, be a slave; that the relation of master and slave is ordained of God; that to send back an escaped bondman to his master is clearly the duty of all the followers of the Lord Jesus Christ; and this horrible blasphemy is palmed off upon the world for Christianity.

Imagine men of God who support slavery – and here he pauses to call out eight by name who place man’s law above God’s law.

The Lords of Buffalo, the Springs of New York, the Lathrops of Auburn, the Coxes and Spencers of Brooklyn, the Gannets and Sharps of Boston, the Deweys of Washington, and other great religious lights of the land have, in utter denial of the authority of Him by whom they professed to be called to the ministry, deliberately taught us, against the example of the Hebrews, and against the remonstrance of the Apostles, that we ought to obey man’s law before the law of God.

Just as David Walker before him, Douglass now issues a warning.

Oh! be warned! be warned! a horrible reptile is coiled up in your nation’s bosom; the venomous creature is nursing at the tender breast of your youthful republic; for the love of God, tear away, and fling from you the hideous monster, and let the weight of twenty millions crush and destroy it forever!… The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity as a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad: it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing and a bye-word to a mocking earth.

The Speech Ends On A Note Of Hopefulness

As Douglass nears closure, he asserts that the U.S. Constitution “is a glorious liberty document,” even though “the inevitable conclusion” must be that the men who wrote it “basely stooped” in regard to slavery.

Your fathers stooped, basely stooped, to palter with us in a double sense, and keep the word of promise to the ear, but break it to the heart.

Therein lies the perfect summary of his entire message. For white America, the Fourth of July represents the fulfillment of the promise of liberty and freedom; for the black slaves, it shouts of a betrayal of basic humanity, that breaks the heart.

But Douglass chooses to end with hope and not despair. He hears “the fiat of the Almighty, Let there be Light” and the coming change in the “affairs of mankind,” the vision of “jubilee.”

I have detained my audience entirely too long already… Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery.

But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind… Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe…

The fiat of the Almighty, “Let there be Light,” has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light…In the fervent aspirations of William Lloyd Garrison, I say, and let every heart join in saying it:

God speed the year of jubilee, The wide world o’er!

When from their galling chains set free, Th’ oppress’d shall vilely bend the knee,

And wear the yoke of tyranny, Like brutes no more.

That year will come, and freedom’s reign.To man his plundered rights again Restore.

God speed the day when human blood Shall cease to flow! In every clime be understood, The claims of human brotherhood, And each return for evil, good,

Not blow for blow;

That day will come all feuds to end,

And change into a faithful friend

Each foe.