Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

Chapter 260: Howell Cobb Resigns From The Cabinet And Urges Georgia To Secede

December 3, 1860

All Sides Attack The President’s Speech

The South is angered by two things in the address: first the President’s assertion that the Constitution prohibits any State from leaving the Union without permission from the other signatories; second that any attempt to seize federal property, such as the Charleston forts, will be met by resistance.

The North regards the address as vintage Buchanan, announcing the dilemma facing the country, acting as if he had no part in its origin, and handing the mess off to Congress to find a solution. Massachusetts congressman Charles Francis Adams, son of the sixth president, finds the message…

…In all respects like the author, timid and vacillating… It satisfied no one and did no service in smoothing the waters.

On the evening of December 3, the Republicans caucus to discuss their response to the president’s call for Congress to take action. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull warns against committees that would surrender the ban on extending slavery in order to placate the South.

For Republicans to take steps toward getting up committees or proposing new compromises is an admission that to conduct the government on the principles on which we carried the election would be wrong.

December 4, 1860

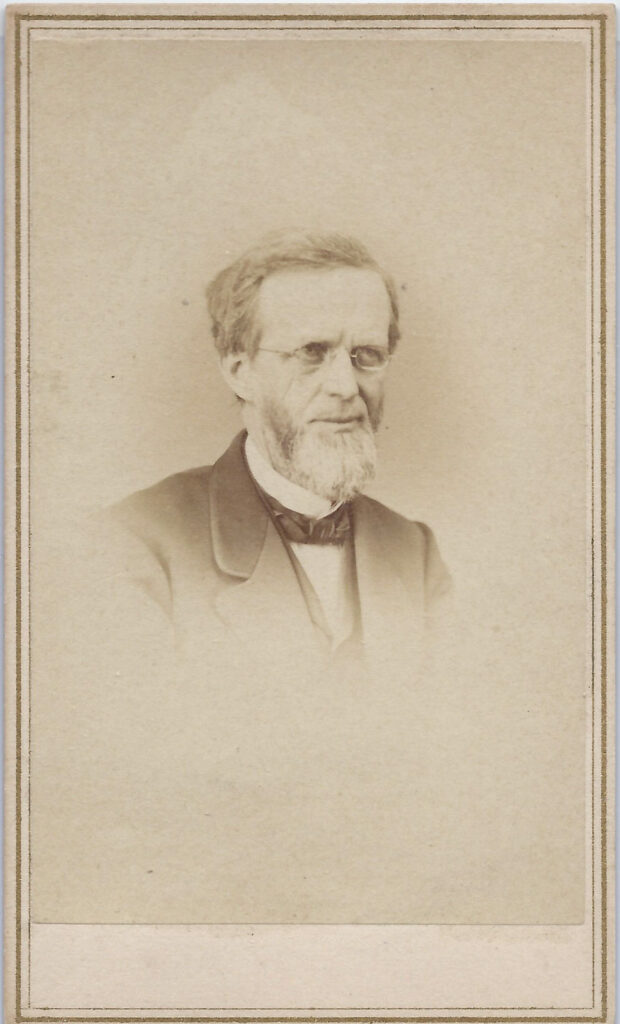

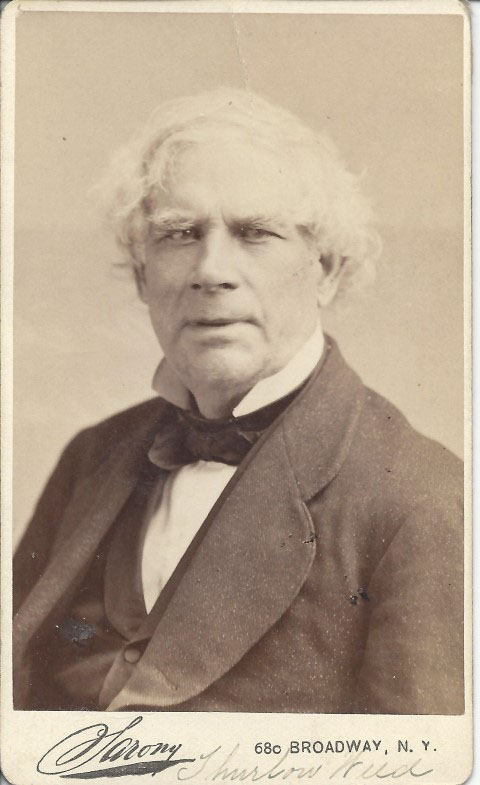

Republican Thurlow Weed Derided For Seeking To Appease The South

Republicans are shocked a day later by an editorial published by one of their chief strategists, Thurlow Weed, in his Albany Evening Journal, calling for the two sides to find a solution before it is too late. This draws immediate fire from his colleagues.

Senator Preston King of New York reprimands Weed:

It cannot be done. You must abandon your position… You and Seward should be among the foremost to brandish the lance and shout for war.

Weed responds by arguing that further dialogue may convince the states in the upper South and the border to stay with the Union. But others simply disagree. Vermont Congressman Justin Morrill’s dissent references Seward’s famous observation about an “irrepressible conflict:”

There can be no compromise short of an entire surrender… the truth (being) there is an irrepressible conflict between our systems of civilization.

Charles Francis Adams seconds the warning that the South still intends to rule and the Republicans must not surrender what they have just won at the polls.

Nothing short of a surrender of everything gained by the election will avail. They want to continue to rule.

Back in Springfield, the intensity of the Southern threat is beginning to dawn one of Lincoln’s campaign advisors, Leonard Swett, who writes:

This flurry at the South can be got along with, but I don’t think it ought to be trifled with.

Lincoln meanwhile feels like his positions have long been spelled out in detail and joining in a new fray would prove futile.

If I were to labor a month, I could not express my conservative views and intentions more clearly and strongly than they are in our platform and in many speeches already in print…anything new would merely be seized on by the ultras and misrepresented.

Let there be no compromise on the question of extending slavery. If there be, all our labor is lost, and, ere long, must be done again. . . . The tug has to come & better now, than any time hereafter.

December 8, 1860

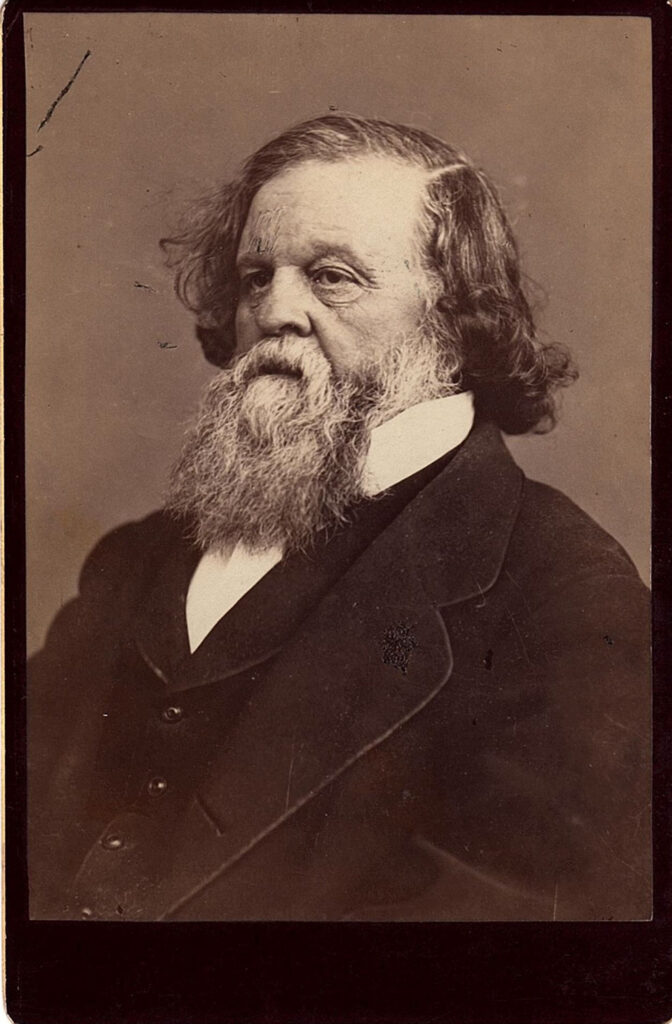

Cobb’s Departure Signals The Coming Secession

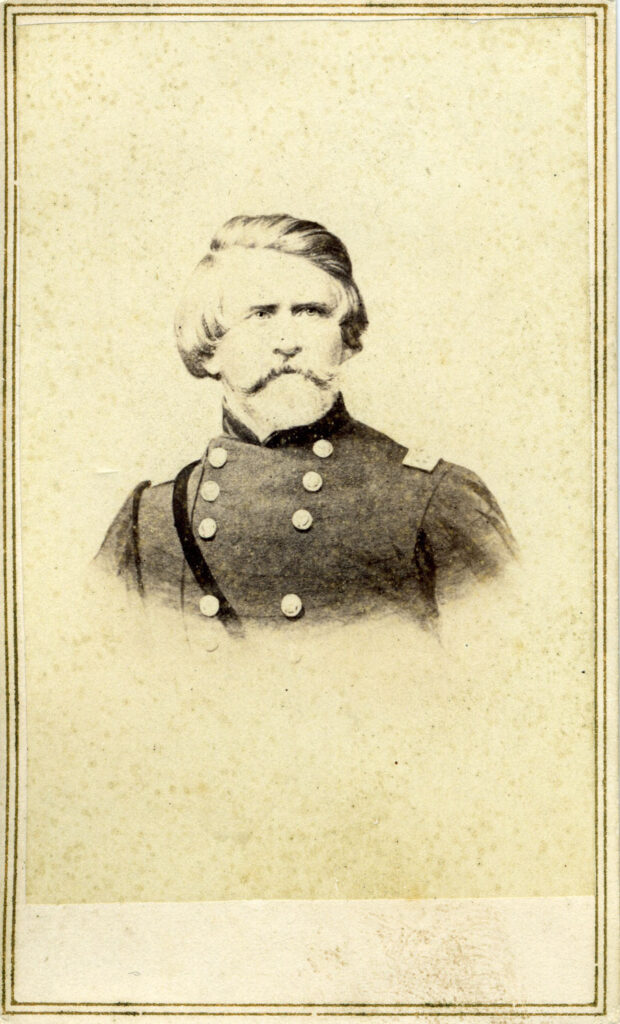

On December 6, 1860, South Carolina congressman Milledge Bonham meets with a cross section of Southern politicians to decide how they want to respond to Buchanan’s warning about secession and the prospect of an adversarial Republican president in the White House.

Bonham then visits Secretary of the Treasury, Howell Cobb, and learns that the strategy among the Southern members of the Cabinet, along with Jefferson Davis, lies in delaying any further confrontations until Buchanan’s term expires in March.

Bonham, whose older brother was killed at the Alamo and who served as a Lt. Colonel in the Mexican War, tells Cobb that stalling is out of the question, especially as it relates to South Carolina.

The State will be eternally…disgraced now if she hesitates.

He also assures Cobb that once South Carolina secedes, other states are certain to follow. The irony here is that, unknown to Bonham, Cobb has already drafted his own Letter to the People of Georgia on the Condition in the Country, laying out the case for leaving the Union.

The Letter recaps in great detail the growing hostility of the North to the institution of slavery, leading up to the emergence of the Black Republican Party, dedicated to the belief…

That slavery is such an evil and curse, that it is the duty of everyone, to the extent of his power, to contribute to its ultimate extinction in the United States.

In his Letter, Cobb goes on the attack against Lincoln for “sentiments more odious than Seward;” John Andrews, the newly elected Massachusetts Governor, for his “declared sanction and approval of the John Brown raid; and finally that other band of abolitionists, “Beecher, Garrison, Cheever, Phillips and Webb.” Together their messages are:

Hatred of slavery, disregard of judicial decisions, negro equality…(and) no such thing as property in our equals.

In the face of this antipathy, Cobb finds some arguing that the South should:

Rely for our safety and protection upon…the two Houses of Congress, and told…(to) delay…(as) the South responds by holding up before them a Constitution basely broken – a compact wantonly violated.

He asks if there is any credible option to “immediate secession” and, in a genuine show of loyalty, cites the “pure of heart” Buchanan as the only one still searching for patriotic solutions.

Is there no other remedy for this state of things but immediate secession? None worthy of your consideration has been suggested, except the recommendation of Mr. Buchanan, of new constitutional guarantees – or rather, the clear and explicit recognition of those that already exist. This recommendation is the counsel of a patriot and a statesman. It exhibits an appreciation of the evils that are upon us, and at the same time a devotion to the Constitution and its sacred guarantees. It conforms to the record of Mr. Buchanan’s life on this distracting question – the record of a pure heart and a wise head.

But the outlook seems futile to Cobb at this point:

The Union formed by our fathers was one of equality, justice and fraternity. On the fourth of March it will be supplanted by a Union of sectionalism and hatred. The one was worthy of the support and devotion of freemen – the other can only continue at the cost of your honor, your safety, and your independence.

In turn he calls upon Georgia to leave the Union.

Fellow-citizens of Georgia, I have endeavored to place before you the facts of the case, in plain and unimpassioned language… You have to deal with a shrewd, heartless and unscrupulous enemy, who in their extremity may promise anything, but in the end will do nothing…

On the 4th day of March, 1861, the Federal Government will pass into the hands of the Abolitionists. It will then cease to have the slightest claim upon either your confidence or your loyalty; and, in my honest judgment, each hour that Georgia remains thereafter a member of the Union will be an hour of degradation, to be followed by certain and speedy ruin. I entertain no doubt either of your right or duty to secede from the Union. Arouse, then, all your manhood for the great work before you, and be prepared on that day to announce and maintain your independence out of the Union, for you will never again have equality and justice in it. Identified with you in heart, feeling and interest, I return to share in whatever destiny the future has in store for our State and ourselves.

On December 8, 1860, Howell Cobb submits his resignation from Buchanan’s cabinet, not without regret, but with conviction that he has no other choice.

His departure is just the first in a steady stream of set-backs coming at the President.