Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

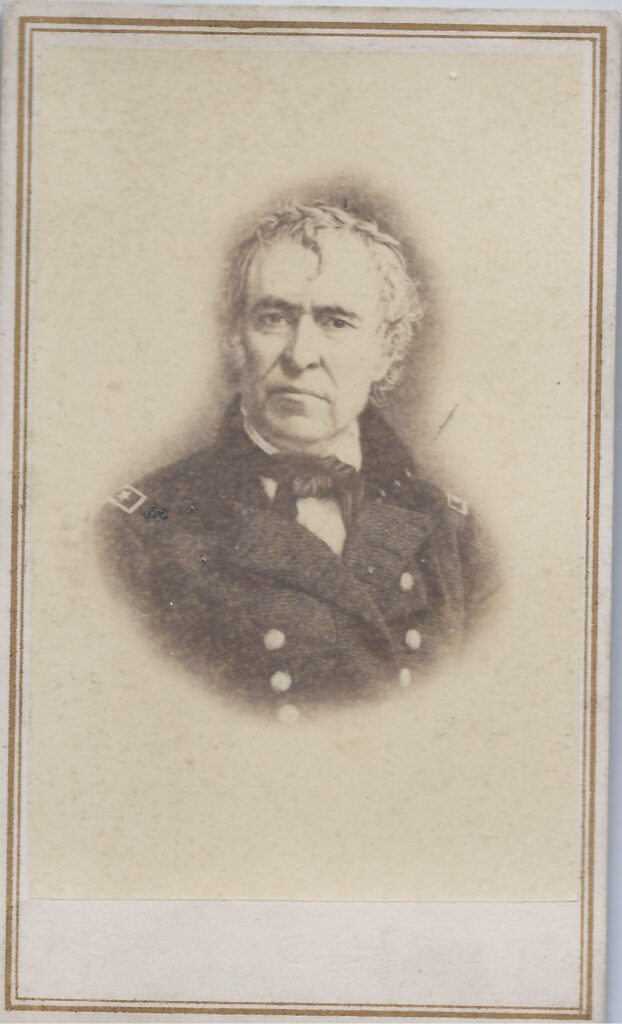

Chapter 125: General Zachary Taylor Wins Lasting Fame At Buena Vista

September – December 1846

General Taylor Drifts Southwest From His Victory At Monterrey

After scoring his decisive victory at Monterrey on September 23, 1846, General Zachary Taylor allows the Mexican army to leave the field, much to the chagrin of Polk and his cabinet.

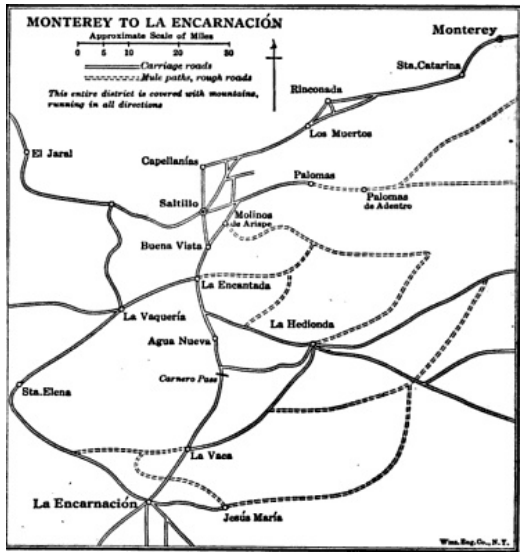

His orders from Washington are to consolidate his hold on Monterrey, but instead he continues westward, taking the town of Saltillo on November 16, and ordering General John Wool to move south to Aqua Nuevo, where he arrives on December 21.

As Taylor drifts further into the interior, Mexican General Ampudia is sacked in favor of the familiar figure of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

His is a chequered past, starting with early support of Spanish rule, then flipping sides after independence is won in 1821 and finally defeating Spain’s attempt to reconquer Mexico at the 1829 Battle of Tampico. This victory makes him a national hero and leads to a political career, whereby he is in and out of the presidency on seven occasions, his last term ending in exile to Cuba after a coup.

But in late 1846 he again “offers his services to the country” to put down the American invaders – just as he did in March 1836 defeating the Texans at The Alamo and then in the Goliad Massacre.

With his return comes a guarantee to the government to stay out of politics, and a secret hint to the U.S. that he is ready to sign a peace treaty. He quickly abandons both promises, re-taking political control in 1847 and fighting tooth and nail against the U.S. invaders.

Santa Anna remains a courageous warrior, despite the loss of his left leg to a cannon ball in 1838.

He is a sound military planner, and also confident of victory – believing that he can first destroy Taylor’s depleted forces up north and then sweep down south on any invaders aiming at Mexico City.

His first move will play out just below the town of Saltillo, at Buena Vista.

February 22-23, 1847

The Battle of Buena Vista Ends The Campaign In Northern Mexico

General Taylor appears to play right into Santa Anna’s hand on February 22, 1847 when his 5,000 man force, heading toward Aqua Nuevo, suddenly finds Santa Anna’s 20,000 man army directly in his front.

Taylor responds quickly by establishing a strong defensive position along the road leading back north to Buena Vista. On the west side of the road are impassable plateaus, while on the east side, where Taylor deploys, are a series of arroyos, or deep gullies, which inhibit massed infantry attacks. Still Santa Anna remains so confident of victory that he sends an emissary to seek immediate surrender – which Taylor promptly declines.

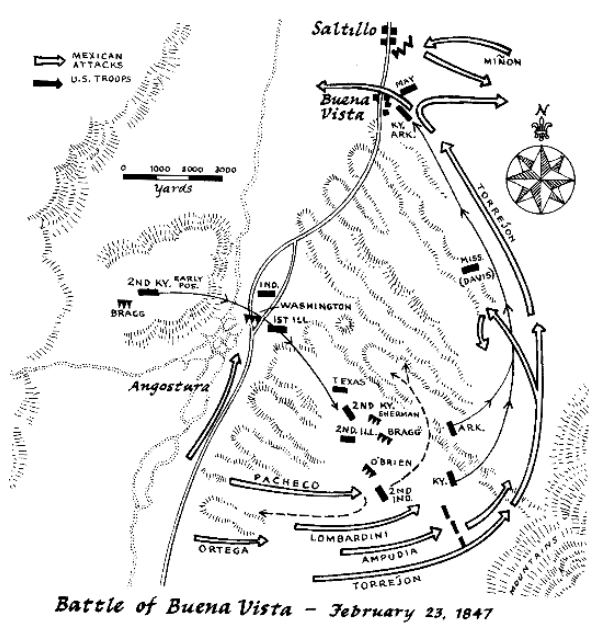

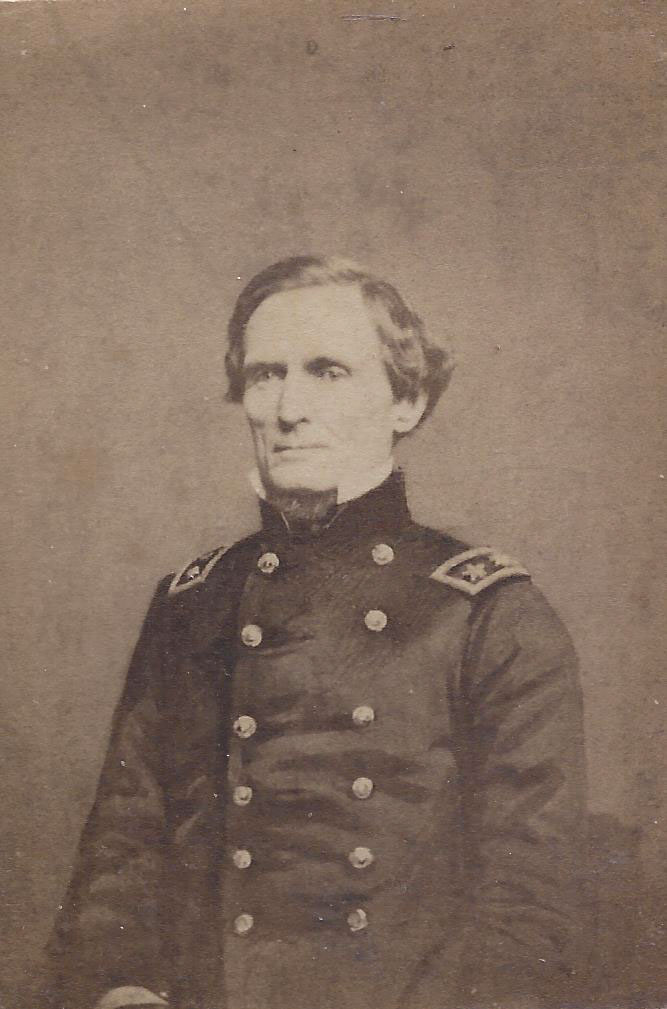

At 8AM on February 23, the Mexicans launch a ferocious two-pronged attack. The main body of their infantry crashes into Taylor’s left center which wavers until pivotal artillery support from Lt. George Thomas and Captain Braxton Bragg stiffens the defense. Meanwhile another contingent of roughly 1500 lancers head far east and north to encircle the American’s left flank. These lancers break through and pose a serious threat to Taylor’s rear – until a courageous rush by Colonel Jefferson Davis and his 7th Mississippi Rifles hurls them back.

Santa Anna still believes by mid-afternoon that the U.S. forces will break under one more concentrated assault. At 5PM he throws everything he has left against the American center and again forces it backwards until Bragg’s flying artillery and Davis’s infantry are once again able to save the day.

When Santa Anna retreats from Buena Vista the next day, his Mexicans will have come as close to securing a battlefield victory as they will at any time during the entire war.

The butcher’s bill for the day of fighting on February 23 is high – with 3700 men killed/wounded/missing on the Mexican side and 750 on the American side. Braxton Bragg (1817-1876)

Two U.S. heroes emerge from the battle.

The first is Zachary Taylor, who, despite disobeying orders and marching into a 4:1 manpower trap, has escaped with another victory to close out his campaign to secure the Rio Grande border for Texas.

The second, ironically, is Taylor’s son-in-law, Jefferson Davis, who suffers a severe wound to his foot at Buena Vista, ending his military duty and leaving him on crutches for two years. He returns as a hero and is chosen by Governor Brown to serve in the U.S. Senate, which is vacant by a death in office.

Davis joins the Senate on August 10, 1847 and immediately becomes a leader in the Democratic Party.

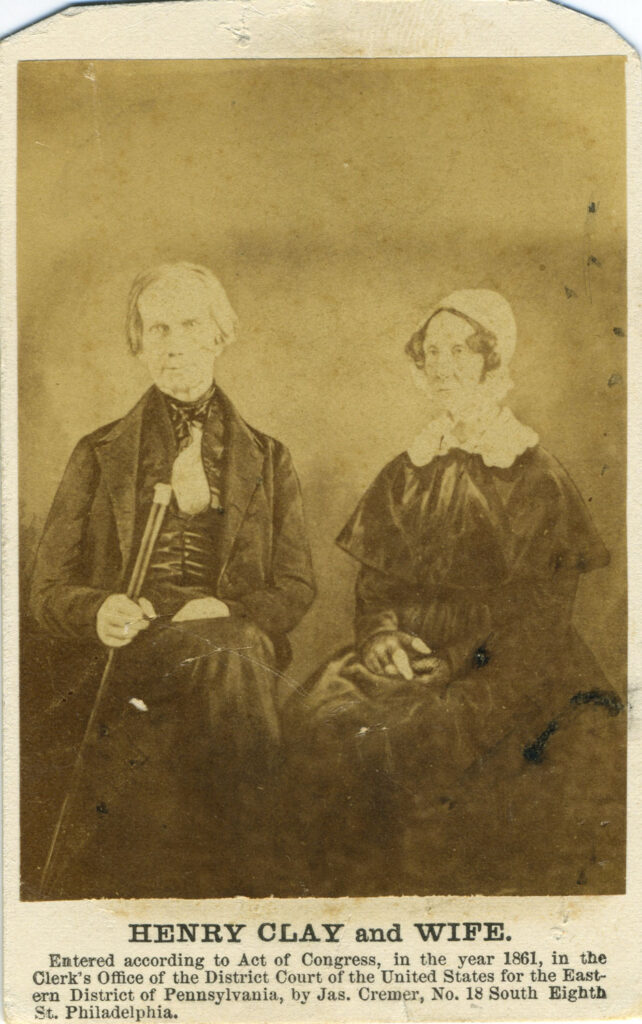

Sidebar: Death of Henry Clay, Jr.

Among those lying dead on the field at Buena Vista is Henry Clay, Jr., age 36, son of a famous father whose presidential ambitions have been derailed by his opposition to the Mexican War.

The younger Clay is the seventh of eleven children in the family, and the one chosen not only to bear his father’s given name but also to follow in his public footsteps.

Unlike his two older brothers, Henry Clay, Jr. exhibits his father’s energy and ambition early in life. After graduating from Transylvania College, he goes on to finish second in his class at West Point in 1831. He resigns his commission, studies the law, and marries the 18-year-old beauty, Julia Prather, in 1832. A single term in the Kentucky House in 1835-36, is followed by overseeing the Ashland Plantation and caring for two of the four children who have survived infancy.

Then, in 1840, his world changes when Julia dies after delivering another son, who survives. But the younger Clay never fully recovers from this loss. He remains dutiful to his family, but loses some of the “purpose” that marked his youth.

The War with Mexico lends him a new cause, a chance to serve his country, in the tradition set by his father. He helps to form the Second Kentucky Volunteer Infantry unit, assuming the rank of Lt. Colonel. He arrives in Mexico, but doesn’t reach Taylor’s command until after the victory at Monterrey. At that point, it looks like he will miss all of the fighting.

On February 23, 1847, however, Taylor, and Clay, are confronted by a Mexican army with a 4-1 manpower advantage, at Buena Vista. The 2nd Kentucky is caught in the front ranks as the battle begins, and is soon overrun by Santa Anna’s forces.

Hart Clay (1781-1864)

Lt. Colonel Henry Clay, Jr. falls with a severe wound in the left thigh. His men attempt to move him to the rear, but they fail, and he hands them his pistols and orders them to flee and save their own lives. When the Mexican lancers arrive on the field, they spear the remaining wounded, including Clay, to death.

After Taylor’s remarkable victory at Buena Vista, Clay’s body is temporarily buried in Saltillo. It rests there until the summer, when the remains of many Kentucky soldiers are re interred in a cemetery in Frankfort. On July 20, 1847, the Clay family, along with some 20,000 other local citizens attend the final service. It becomes immortalized in a long poem – The Bivouac of the Dead – written by a Kentucky trooper named Theodore O’Hara. The opening stanza:

The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat

The soldier’s last tattoo;

No more on life’s parade shall meet

The brave and daring few.

On Fame’s eternal camping-ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards with solemn round

The bivouac of the dead

For the seventy-year-old Henry Clay, and his aging wife, Lucretia, the day is marked by deep sadness, rather than glory. They have just lost the seventh of their eleven children, and here in a war that Clay has already called “calamitous, as well as unjust and unnecessary.”