Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 124: Congress Debates The Morality And Implications Of The Mexican War

December 7, 1846

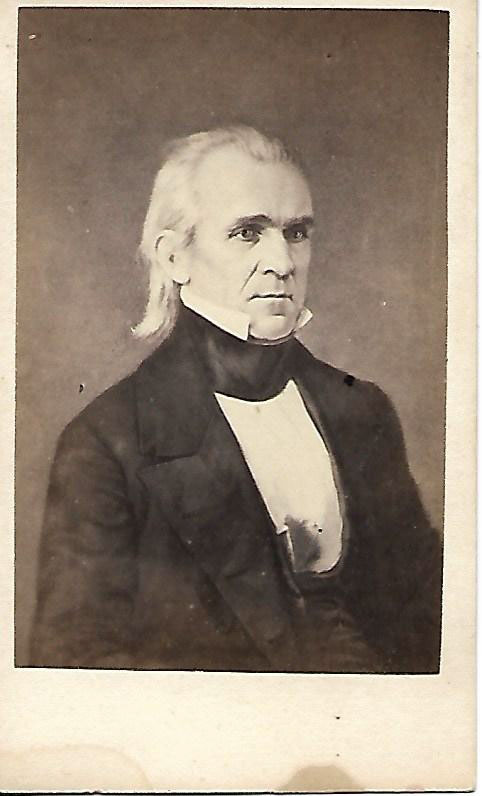

Polk Tries To Stem Divisiveness In His Annual Address To Congress

Polk’s words show that he is clearly alarmed by the House vote on the Wilmot Proviso, which leaves him without funding for the war and with disunity in his own party over the future expansion of slavery.

The slavery question is assuming a fearful and most important aspect.

When the second and final session of the 29th Congress reconvenes on December 7, 1846, his Annual Message first attempts to align all sides behind his war efforts. His address begins with reassurances that the intent of the war is not to annihilate Mexico, and that the wish is end it as soon as the enemy will accept peace terms.

In my (last) annual message…I declared that– The war has not been waged with a view to conquest, but, having been commenced by Mexico, it has been carried into the enemy’s country and will be vigorously prosecuted there with a view to obtain an honorable peace….It has never been contemplated by me, as an object of the war, to make a permanent conquest of the Republic of Mexico or to annihilate her separate existence as an independent nation….Whilst our armies have advanced from victory to victory from the commencement of the war, it has always been with the olive branch of peace in their hands, and it has been in the power of Mexico at every step to arrest hostilities by accepting it.

He then turns to the delicate topic of slavery, not mentioning it explicitly, rather choosing to invoke the memory of George Washington and his warnings about geographical divisiveness as a threat to the Union.

(Washington) that greatest and best of men foresaw… the danger to our Union of “characterizing parties by geographical discriminations–Northern and Southern, Atlantic and Western–whence designing men may endeavor to excite a belief that there is a real difference of local interests and views,” and warned his countrymen against it.

So deep and solemn was his conviction of the importance of the Union and of preserving harmony between its different parts, that he declared to his countrymen in that address: It is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you indignantly frown upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts. After the lapse of half a century these admonitions of Washington fall upon us with all the force of truth.

From there he boldly attempts to dismiss the battle over the Wilmot Proviso as nothing more than “differences of opinion upon minor questions of public policy.”

It is difficult to estimate the “immense value” of our glorious Union… How unimportant are all our differences of opinion upon minor questions of public policy compared with its preservation, and how scrupulously should we avoid all agitating topics which may tend to distract and divide us into contending parties, separated by geographical lines, whereby it may be weakened or endangered.

Polk’s message on December 7, 1846 is one that both he and his immediate successors will wish to believe – that sectional resistance to the presence of Africans, either slave or free, west of the Mississippi is nothing more than a minor diversion.

Going forward, Congress should simply “avoid (these) agitating topics which may tend to distract and divide” the country.

January 16, 1847

The House Debates Legal Precedents For Declaring Oregon A “Free State”

Despite Polk’s plea, the political jockeying over extending slavery into new western territory resumes early in the new session.

The initial focus is not the Southwest, but rather the Oregon Territory.

While all sides agree that Oregon should be declared a “Free State,” they argue over the legal basis for the call.

The rationale cannot be the Wilmot Proviso, since Oregon is acquired in the June 1846 treaty with Britain, and does not involve territory associated with the Mexican War.

But why then should Oregon have Free State status?

Southern members, led by Calhoun’s man, Armistead Burt of South Carolina assert that the precedent should be the 1820 Missouri Compromise, simply extending the 34’30” line to the west coast. This is the same proposal offered six months earlier by Indiana’s William Wick and supported by Stephen Douglas.

Again it meets resistance. Congressman Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, an outspoken abolitionist, says that the Missouri line “has no more application to the territory of Oregon than it has with the East Indies.”

A contrived rationale finally emerges around the 1797 Northwest Ordinance ban on slavery, and it musters enough votes to ram the bill through a still rebellious House, on January 16, 1847.

The bill declaring Oregon a Free State goes on to the Senate, where it is immediately tabled.

February 11, 1847

Tom Corwin Warns Of The Damage To Follow From The Mexican War

The next volley over slavery comes when the Senate turns to a modified request from Polk for funds to prosecute the war with Mexico.

The ante has now risen from $2 million to $3 million, as it becomes clear that a more substantial invasion will be required to force an end to the fighting.

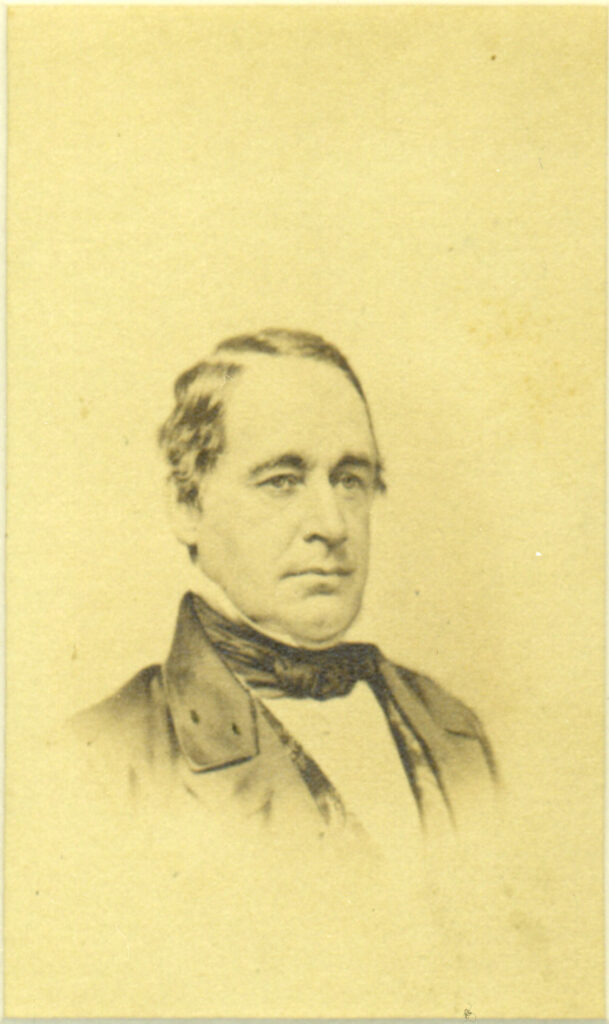

The leading spokesman for the Whigs is the ex-Governor now Senator from Ohio, Tom Corwin.

Corwin addresses his colleagues on February 11, 1847 in an eloquent and balanced speech, intended to challenge Polk’s justification of the Mexican War and to warn members that geographical divisions over slavery is destined to lead on to “civil conflict.”

Corwin begins by recalling Mexico’s recent struggle for freedom from Spain, from Father Hidalgo’s “cry” (“El Grito de la Independencia”) at the town of Dolores in 1810 to the final Treaty of Cordova in 1821. And now, says Corwin, America comes as a new invader, seeking land the Mexicans bled over.

What is the territory, Mr. President, which you propose to wrest from Mexico? It is consecrated to the heart of the Mexican by many a well-fought battle with his old Castilian master. His Bunker Hills, and Saratogas, and Yorktowns are there! The Mexican can say, “There I bled for liberty! and shall I surrender that consecrated home of my affections to the Anglo-Saxon invaders? What do they want with it? They have Texas already.

The Senator then looks directly at the topic that Polk has treated in elliptical fashion – the potential for a war of acquisition to divide the Union over the issue of expanding slavery.

There is one topic connected with this subject which I tremble when I approach, and yet I cannot forbear to notice it. I allude to the question of slavery.

Opposition to its further extension, it must be obvious to everyone, is a deeply rooted determination With men of all parties in what we call the nonslaveholding states. New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, three of the most powerful, have already sent their legislative instructions here. So it will be, I doubt not, in all the rest.

How is it in the South? Can it be expected that they should expend in common their blood and their treasure in the acquisition of immense territory, and then willingly forgo the right to carry thither their slaves, and inhabit the conquered country if they please to do so? Nay, I believe they would even contend to any extremity for the mere right, had they no wish to exert it.

Once divided, Corwin argues, the result will be a civil conflict at home – which means, in turn, that bills calling to continue and fund the war are nothing less than “treason to the Union.”

I believe (and I confess I tremble when the conviction presses upon me) that there is equal obstinacy on both sides of this fearful question

This bill would seem to be nothing less than a bill to produce internal commotion. Should we prosecute this war another moment, or expend one dollar in the purchase or conquest of a single acre of Mexican land, the North and the South are brought into collision on a point where neither will yield.

Why should we precipitate this fearful struggle, by continuing a war the result of which must be to force us at once upon a civil conflict? Sir, rightly considered, this is treason, treason to the Union, treason to the dearest interests, the loftiest aspirations, the most cherished hopes of our constituents. It is a crime to risk the possibility of such a contest. It is a crime of such infernal hue that every other in the catalogue of iniquity, when compared with it, whitens into virtue.

The only way out is to abandon the war with Mexico, along with its demands for land beyond Texas. Mexico already knows that it cannot prevail on the battlefield, so peace terms will be readily accepted.

Let us abandon all idea of acquiring further territory and by consequence cease at once to prosecute this war. Let us call home our armies, and bring them at once within our own acknowledged limits. Show Mexico that you are sincere when you say you desire nothing by conquest. She has learned that she cannot encounter you in war, and if she had not, she is too weak to disturb you here. Tender her peace, and, my life on it, she will then accept it.

Once cleansed of Mexican blood, Corwin says, America can escape the prospect of its own civil war and restore “ancient accord and eternal brotherhood” at home.

Let us then close forever the approaches of internal feud, and so return to the ancient concord and the old ways of national prosperity and permanent glory. Let us here, in this temple consecrated to the Union, perform a solemn lustration; let us wash Mexican blood from our hands, and on these altars, and in the presence of that image of the Father of his Country that looks down upon us, swear to preserve honorable peace with all the world and eternal brotherhood with each other.

February 15, 1847

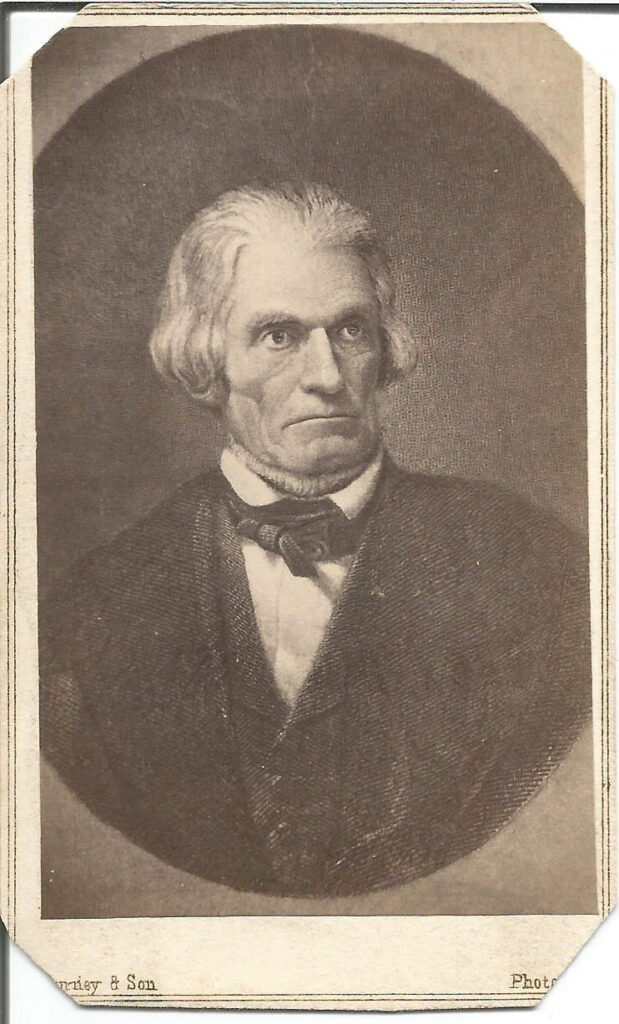

Senator John Calhoun Issues A Southern Warning Over Wilmot

Like Corwin, John Calhoun of South Carolina is another prescient commentator on the consequences of the war and of the Wilmot bill. He sums up his thoughts in a senate speech delivered four days later.

The ever dour Calhoun begins by summing up the situation in congress as he sees it – with non-slaveholding states in both chambers apparently determined to prohibit slavery in the new “public domain” lands to the west.

Mr. President, I rise to offer a set of resolutions in reference to the various resolutions from the State legislatures upon the subject of what they call the extension of slavery, and the proviso attached to the House bill…

It was solemnly asserted on this floor…that all parties in the non-slaveholding States had come to a fixed and solemn determination…that there should be no further admission of any States into this Union which permitted, by their constitutions, the existence of slavery; and…that slavery shall not hereafter exist in any of the territories of the United States; the effect of which would be to give to the non-slaveholding States the monopoly of the public domain… At the same time, two resolutions which have been moved to extend the compromise line from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific, during the present session, have been rejected by a decided majority… It is a scheme, Mr. President, which aims to monopolize the powers of this Government and to obtain sole possession of its territories.

The slaveholding states, he says, are already in the minority in the House (138-90) and in the Electoral College (168-118).

Sir, already we —I use the word “we” for brevity’s sake—are already we are in a minority in the other House, in the electoral college, and I may say, in every department of this Government, except at present in the Senate of the United States—there for the present we have an equality.

There are two hundred and twenty-eight representatives, including Iowa, which is already represented there. Of these, one hundred and thirty-eight are from non slaveholding States, and ninety are from what are called the slave States—giving a majority, in the aggregate, to the former of forty-eight. In the electoral college there are one hundred and sixty-eight votes belonging to the non-slaveholding States, and one hundred and eighteen to the slaveholding, giving a majority of fifty to the non slaveholding.

Only in the Senate do the slaveholding states retain enough voting power to block the will of the majority, and this is transitory. The admission of Iowa and Wisconsin will give the Free States a 32-28 edge in Senate seats, and if 12-15 more Free States are added, the South will be further overwhelmed.

We, Mr. President, have at present only one position in the Government, by which we may make any resistance to this aggressive policy which has been declared against the South…And this equality in this body is one of the most transient character. Already Iowa is a State…Already Wisconsin has passed the initiatory stage, and will be here the next session. This will add…four in this body on the side of the non-slaveholding States, who will thus be enabled to sway every branch of this Government at their will and pleasure.

Sir, there is ample space for twelve or fifteen of the largest description of States in the territories belonging to the United States…. How will we then stand? There will be but fourteen on the part of the South—we are to be fixed, limited, and forever—and twenty-eight on the part of the non-slaveholding States! Twenty-eight! Double our number! And with the same disproportion in the House and in the electoral college! The Government, Sir, will be entirely in the hands of the non-slaveholding States—overwhelmingly. …If this scheme should be carried out…wo! wo! I say, to this Union!

This brings Calhoun to a favorite theme of his, echoed over decades: the need for the majority to avoid trampling on the wishes of the minority. So, he says, if the North denies the rights and the needs of the South on slavery, there will follow revolution, civil war, and disaster.

Sir, the day that the balance between the two sections of the country …is destroyed, is a day that will not be far removed from political revolution, anarchy, civil war, and widespread disaster.

His solution is forever grounded in the literal words and promises of the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing “perfect equality” for all. It says that each man has the right to transport their “property” (in the form of slaves) into any state or territory they choose. The majority simply cannot deny that guarantee without violating the law.

Now, Sir, I put again the solemn question—Does the constitution afford any remedy? The whole system is based on justice and equality—perfect equality between the members of this republic. Now, can that be consistent with equality which will make this public domain a monopoly on one side—which, in its consequences, would place the whole power in one section of the Union, to be wielded against the other sections? Is that equality?

And is it consistent with justice—is it consistent with equality, that any portion of the partners, outnumbering another portion, shall oust them of this common property of theirs—shall pass any law which shall proscribe the citizens of other portions of the Union from emigrating with their property to the territories of the United States?

Furthermore, the essence of American democracy lies with the right of the people “to establish what government they may think proper for themselves.” It is simply an “outrage against the constitution” to demand that the people in all new territories must ban slavery before being admitted to the Union.

Mr. President… that proposition…which undertakes to say that no State shall be admitted into this Union which shall not prohibit by its constitution the existence of slaves, is equally a great outrage against the constitution of the United States.

Sir, I hold it to be a fundamental principle of our political system that the people have a right to establish what government they may think proper for themselves; that every State about to become a member of this Union has a right to form its government as it pleases; and that, in order to be admitted there is but one qualification, and that is, that the Government shall be republican.

And yet, Sir, there are men of such delicate feeling on the subject of liberty—men who cannot possibly bear what they call slavery in one section of the country—although not so much slavery, as an institution indispensable for the good of both races—men so squeamish on this point, that they are ready to strike down the higher right of a community to govern themselves.

Calhoun turns to extending the 34’30” Missouri line as a possible compromise. Ever the purist, he argues that the line has always been unconstitutional – before saying that he would “acquiesce to it to preserve the peace of the Union.”

Mr. President, the resolutions that I intend to offer present, in general terms, these great truths…Overrule these principles, and we are nothing! Preserve them, and we will ever be a respectable portion of the Union.

Sir, here let me say a word as to the compromise line. I have always considered it as a great error—highly injurious to the South, because it surrendered, for mere temporary purposes, those high principles of the constitution upon which I think we ought to stand. I am against any compromise line. Yet I would have been willing to acquiesce in a continuation of the Missouri compromise, in order to preserve, under the present trying circumstances, the peace of the Union…. But it was voted down by a decided majority. It was renewed by a gentleman from a non-slaveholding State, and again voted down by a like majority.

I see my way in the constitution. I cannot in a compromise. A compromise is but an act of Congress. It may be overruled at any time. It gives us no security. But the constitution is stable. It is a rock. On it we can stand…. Let us be done with compromises. Let us go back and stand upon the constitution!

Nearing the end of his speech, the sixty-four year old South Carolina planter reflects on his personal history and his commitment to not surrendering his sense of honor, to “not sinking down into acknowledged inferiority.”

But I may speak as an individual member of that section of the Union. Here I drew my first breath; there are all my hopes. There is my family and connections. I am a planter— a cotton-planter. I am a Southern man and a slaveholder—a kind and a merciful one, I trust—and none the worse for being a slaveholder. I say, for one, I would rather meet any extremity upon earth than give up one inch of our equality—one inch of what belongs to us as members of this great republic! What acknowledge inferiority! The surrender of life is nothing to sinking down into acknowledged inferiority!

He closes with his four proposed “resolutions” to protect the rights of the slaveholding states under the constitution.

Resolved, That the territories of the United States belong to the several States composing this Union, and are held by them as their joint and common property.

Resolved, That Congress, as the joint agent and representative of the States of this Union, has no right to make any law, or do any act whatever, that shall directly, or by its effects, make any discrimination between the States of this Union, by which any of them shall be deprived of its full and equal right in any territory of the United States, acquired or to be acquired.

Resolved, That the enactment of any law, which should directly, or by its effects, deprive the citizens of any of the States of this Union from emigrating, with their property, into any of the territories of the United States, will make such discrimination, and would, therefore, be a violation of the constitution and the rights of the States from which such citizens emigrated, and in derogation of that perfect equality which belongs to them as members of this Union—and would tend directly to subvert the Union itself.

Resolved, That it is a fundamental principle in our political creed, that a people, in forming a constitution, have the unconditional right to form and adopt the government which they may think best calculated to secure their liberty, prosperity, and happiness; and that, in conformity thereto, no other condition is imposed by the Federal Constitution on a State, in order to be admitted into this Union, except that its constitution shall be republican; and that the imposition of any other by Congress would not only be in violation of the constitution, but in direct conflict with the principle on which our political system rests.”

In February 1847, Calhoun’s speech is regarded as radical, just one more attempt on his part to run for the presidency. A decade later, after his death, it will reflect the sentiments of most men across the South.

February 15, 1847

The House Passes A New And Harsher Proviso On Expanding Slavery

While the debate continues in the Senate, the House takes up the Three Million Dollar Bill to fund the war.

Once again, the New York “Barnburner,” Preston King, proposes an amendment in the form of a revised version of the Wilmot Proviso.

King’s version is even more onerous to the South than Wilmot’s. It declares that slavery be banned in “any territory on the continent of America which shall hereafter be acquired.” This being a direct shot at expansionists who wish to annex all of Mexico and Cuba and perhaps even parts of Central America.

Polk calls this a “mischievous and foolish amendment…with (no) connection to making peace with Mexico.”

Regardless, the House passes the bill on February 15 by a margin of 115-106 and sends it to the Senate.